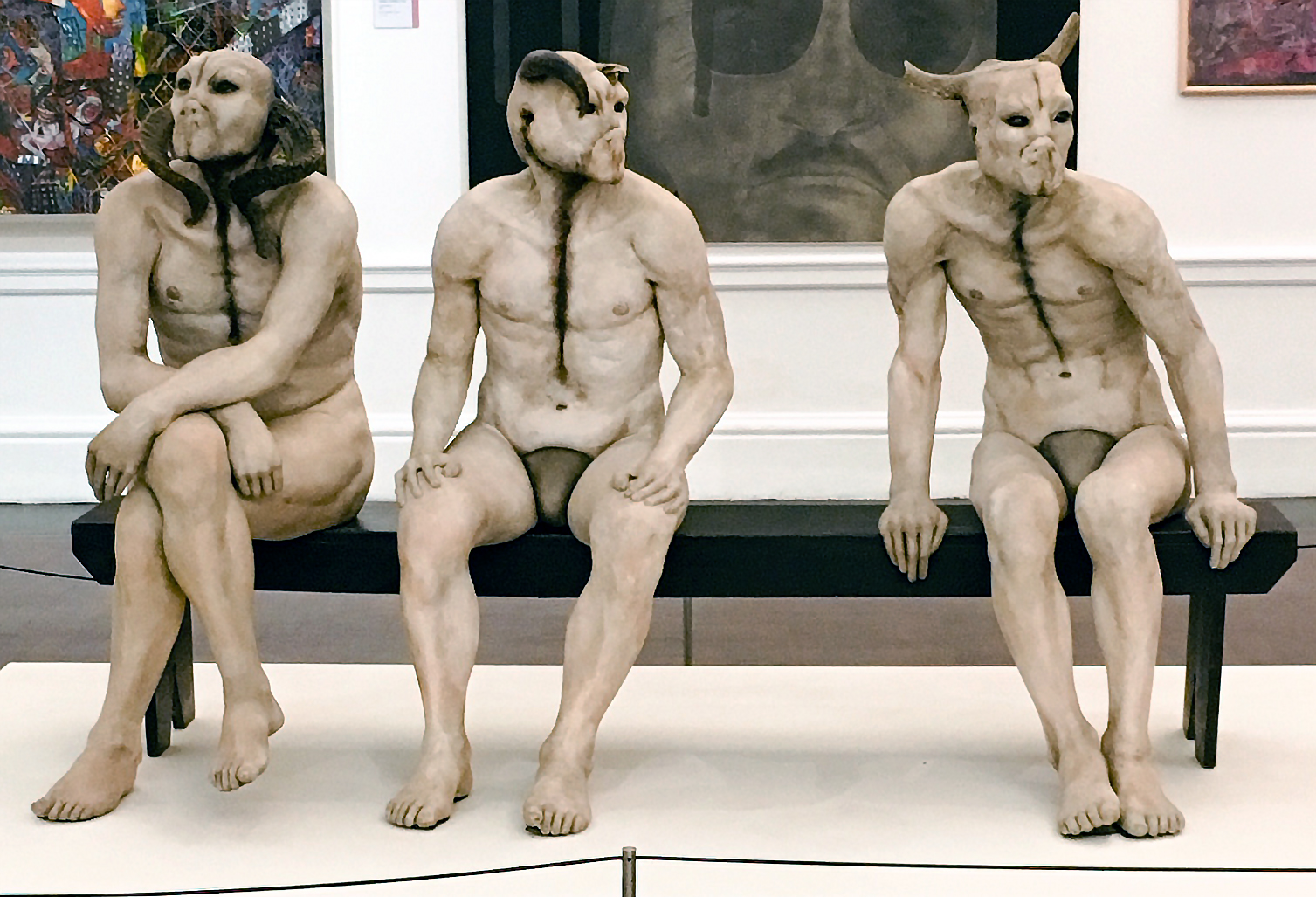

Jane Alexander, Butcher Boys, 1985/86, mixed media (Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town, photo: Goggins World, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Men or beasts?

Inside the Iziko South African National Gallery there are three monstrous figures that sit casually on a wooden bench thoroughly indifferent to their environment. Their indifference confounds gallery-goers who struggle to answer questions such as: Are these figures men or beasts? What do these figures represent? South African artist Jane Alexander created the life-sized sculpture, titled Butcher Boys, in 1985/86 while a graduate student at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. The figures are composed of reinforced plaster, animal bones, horns, oil paint, and the wooden bench on which they sit.

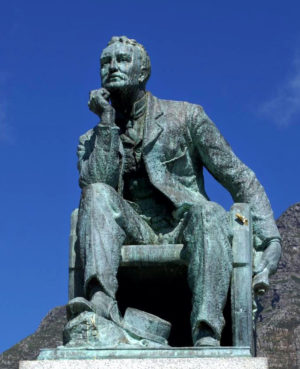

Marion Walgate, Cecil John Rhodes, 1934 (University of Capetown, photo: Danie van der Merwe, CC BY 2.0)

Uncanny resemblance

The forceful impact of the Butcher Boys resides in the figures’ uncanny resemblance to us. Their figures are not all together unfamiliar within the history of art. There are flashes of resemblances to the familiar and celebrated figurative sculptures of the Greco-Roman tradition. The scale, definition in form, and physical proportions seen in Alexander’s Butcher Boys echo those of the Hellenistic Boxer at Rest by Apollonius. Other stylistic associations to seated and contemplative figures, such as the now notorious monument to Cecil John Rhodes, can also be made.

Jane Alexander, Butcher Boys, 1985/86, mixed media (Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town, photo: Ctac, CC BY-SA 3.0)

However, Alexander’s figures are not, of course, continuations of these figurative traditions. Rather, hers are a critique in which she transforms the symbolic body of heroic/stately strength into a grotesque mockery of classicism. Their scarred flesh, exposed spinal bones, horned crania, and vacant black eyes undermine any sense of beauty to be found in their carefully modeled bodies. The Butcher Boys discomforts us because their form comes too close to that of humans, yet their anatomy is riddled with nonhuman elements and mutations. Alexander has eliminated, or grossly mutated, each figure’s sense of sound, sight, smell, and taste. Each figure has irregular concavities where, perhaps, ears once protruded, but have otherwise been removed. They have the slightest suggestion of nasal cavities, which makes their lack of any oral cavity all the more prominent and perplexing. Additionally, deep scars traverse the larynx, past the heart and end just above the navel. Their limbs and torsos are decidedly human. Their arms and legs are without mutation, however, deep wounds down their spinal columns expose fragments of bones.

Viewers of the Butcher Boys confront an uncanny image of brutalization. The figures are not sympathetic victims or overtly threatening monsters. They are intimidating; yet, the violence against their bodies elicits a certain amount of empathy. They are unnamable beings without classification. They are neither man nor beast but rather both.

Jane Alexander, Butcher Boys, detail, 1985/86, mixed media (Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town, photo: Goggins World, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Crime against humanity

The National Party in South Africa came to power in 1948 and was founded on white-supremacy and driven by an ideological platform of extreme segregation known as apartheid, or in Afrikaans, “apartness” or “apart-hood.” In 1985, the same year Alexander created Butcher Boys, South Africa was consumed by violent and non-violent resistance to apartheid. This was followed by a state of emergency (the second) issued by the National Party and state-sanctioned violence.

The earliest apartheid laws were distinctly concerned with the control and management of South Africans to assert and maintain white supremacy. The first two laws passed by the apartheid government were anti-miscegenation laws that criminalized marriage and sexual relations between “a European and a non-European.” The third, the “Population Registration Act” of 1950, forced citizens to register with the government according to its racial caste system. By 1973 the General Assembly of the United Nations recognized South African apartheid as a “crime against humanity.” This reality, of course, had long been recognized by those who fought against the regime. Despite growing international condemnation and internal resistance, the National Party continued to violently oppress any challenge to their power throughout the later decades of the 20th century. Given this context of brutality, Alexander’s Butcher Boys are commonly linked to the violence of apartheid and particularly the second state emergency. Art critic Ivor Powell wrote that “the Butcher Boys . . . [is] probably the most enduringly iconic image of the sinister and apocalyptic brutalisations of apartheid.”[1]

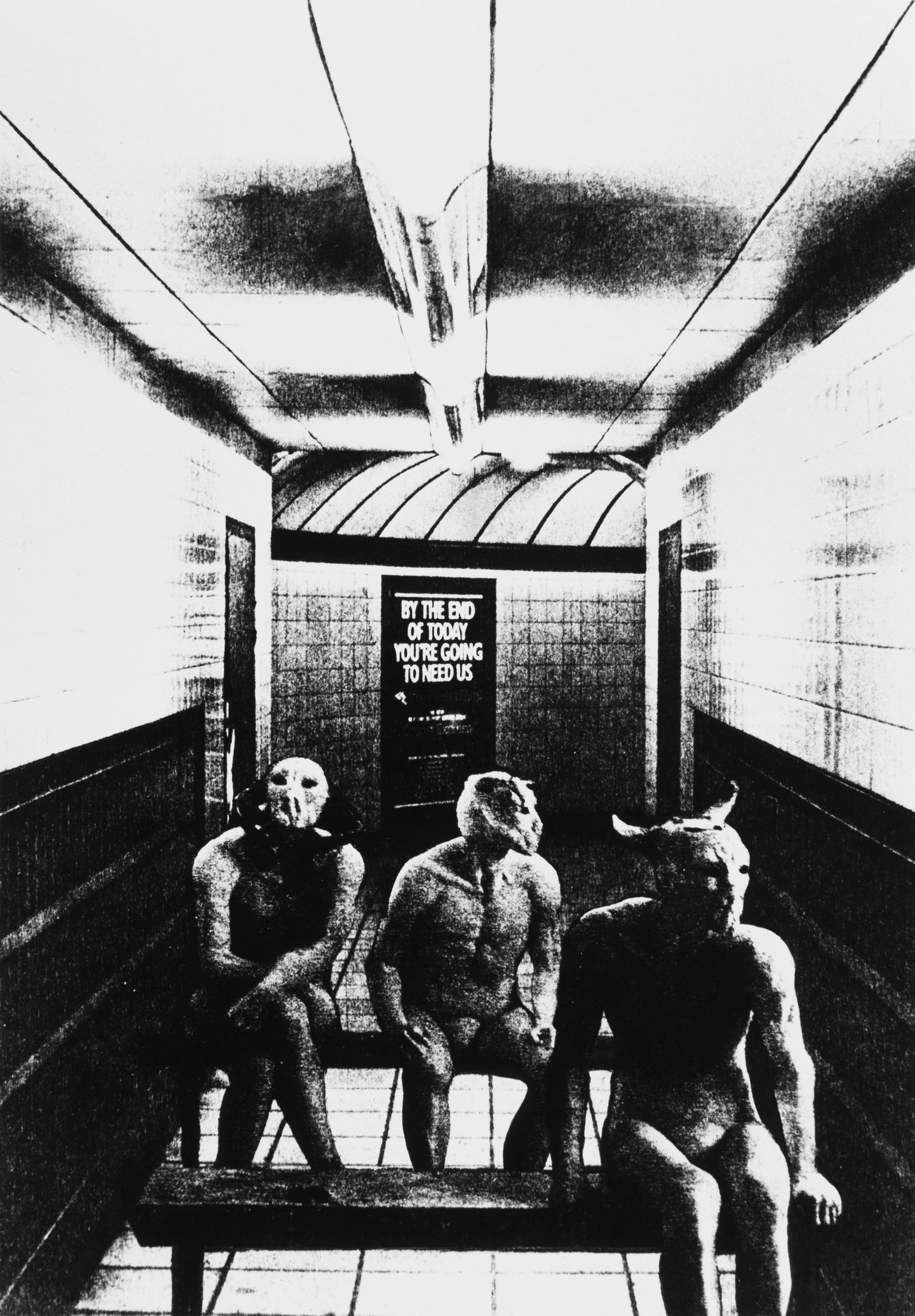

Jane Alexander, BY THE END OF TODAY YOU’RE GOING TO NEED US, 1986, fibre-based silver print, 29 x 20 cm (Stevenson)

Art, trauma, and political violence

Alexander, featured the Butcher Boys in photomontages, such as BY THE END OF TODAY YOU’RE GOING TO NEED US (1986), Ford (1986), and Transmitter (2007) among others. Since they are so commonly associated with apartheid violence and trauma, their presence becomes a potent symbol of that violence and trauma. Through the repetition of their image in photomontages, outside of the white-walled gallery space, Alexander appears to provide evidence of the Butcher Boys’ existence within our world. In these photomontages, Alexander blurs and obscures the visual field just enough to give a candid or accidental aura to each image. It’s as if the Butcher Boys are unwitting subjects within the series of photographs taken from everyday life.

By placing the Butcher Boys in a variety of scenes—on the outskirts of Cape Town, within a salvage yard, and waiting for a subway train—Alexander moves the audience beyond the physical components of the Butcher Boys and into a deeper consideration of their existence. This is the key to the work’s iconic status. It is not just the shock of the physical, but even more so, the chilling recognition of the environment as the source of their trauma.

Jane Alexander, Butcher Boys, detail, 1985/86, mixed media (Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town, photo: Ctac, CC BY-SA 3.0)

What Alexander achieved with Butcher Boys can be likened to Picasso’s Guernica. Both were created in the context of atrocities, which the governments (Franco’s Spain and the National Party’s South Africa respectively), inflicted on their own people. Guernica is so named because it depicts the bombing of a civilian target, the Basque city of Guernica in Spain. Its subject is local and specific; however, its reception propelled it into a totalizing indictment of fascism, much in the same way that Goya’s Third of May, 1808 depicts the events of a singular day of Napoleonic violence in Spain, but has come to represent the horrors of war more generally.

Francisco de Goya, Third of May, 1808, 1814, oil on canvas, 266 x 345.1 cm (Museo del Prado. Madrid)

Both Picasso’s and Goya’s paintings highlight an unsettling normalization of political violence. They give their viewers a chilling assessment of the unaffected banality of the environments from which these atrocities sprang. In so doing, these paintings resonate beyond their record of time and artistic movements as they reflect our seemingly endless slippage into enacting and accepting brutal violence. What sets Alexander’s Butcher Boys apart from Picasso’s and Goya’s iconic paintings is that her work does not point to a singular event. Rather it is the totality of the apartheid’s regime of violence that is called into question.

The Butcher Boys may be part man and part beast. Their identity as such, however, is less important than what they represent—violence and trauma. The Butcher Boys can be seen as a response to the public’s willingness to depersonalize violence by ascribing such behavior to the monstrous. To acknowledge the truly violent nature of humankind is to implicate one’s self in a relationship to such atrocities. These bodies visualize violence in a way that emphasizes how we dehumanize each other. It is easier to dehumanize violence than it is to see humanity in violence, and this transitional state of being between man and monster is where the Butcher Boys reside.

Notes:

- Ivor Powell, “Inside and Outside of History,” Art South Africa vol. 5, no. 4 (Winter 2007), pp. 32-38.

Additional resources:

Iziko South African National Gallery

Tate Modern, “Who is Jane Alexander?”

South African History Online, “Jane Alexander”

Pep Subirós, ed., Jane Alexander: Surveys from the Cape of Good Hope (New York: Museum of African Art, 2011).

Sophie Perryer, ed., Personal Affects: Power and Poetics in Contemporary South African Art (New York: Museum of African Art, 2004).

Sue Williamson, Resistance Art in South Africa (Southern Africa: David Philip, Publisher, 1989).