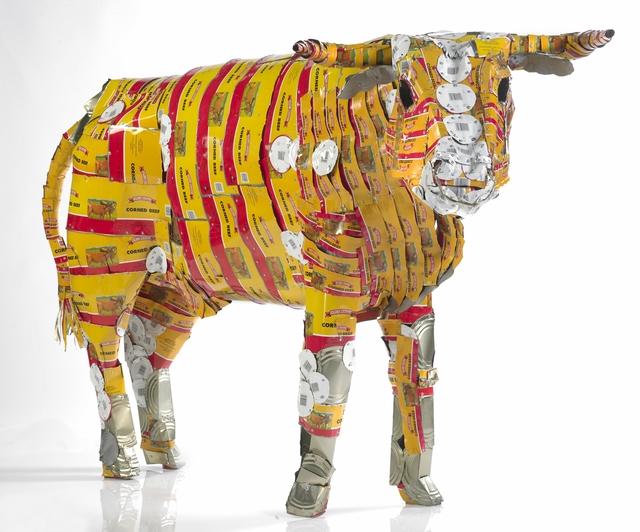

Michel Tuffery, Pisupo Lua Afe (Corned Beef 2000), 1994, flattened cans of corned beef (Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Collection) ©Michael Tuffery

What can a tin can bull teach us about ecological and population health issues in the Pacific? Michel Tuffery is one of New Zealand’s best-known artists of Pacific descent, with links to Samoa, Rarotonga and Tahiti. He majored in printmaking at Dunedin’s School of Fine Arts, and describes art quite literally as his first language because he didn’t read, write or speak until he was 6 years old. Encouraged instead to express himself through drawing, he now aims artworks like Pisupo Lua Afe primarily at children, hoping to engage their curiosity and inspire them to care for both their own health and that of the environment.

Pisupo Lua Afe is one of Tuffery’s most iconic works, made from hundreds of flattened corned beef tins, riveted together to form a series of life-sized bulls. Despite evident connections to Pop Art, especially Andy Warhol’s celebrations of the humble Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962), it’s impossible to read this work solely in the terms of Western art history. So what is Tuffery trying to tell us?

Pisupo—canned food in the Pacific

Pisupo is the Samoan language version of “pea soup,” which was the first canned food introduced into the Pacific Islands. Pisupo is now a generic term used to describe the many types of canned food that are eaten in the Islands—including corned beef. Not only is corned beef a favorite food source in the Islands, it has also become a ubiquitous part of the ceremonial gift economy. At weddings and birthdays, and other important life events both in the Islands and in Islander communities in New Zealand, gifts of treasured textiles like fine mats and decorated barkcloths are made alongside food items and cash money. But unlike the Island feast foods gifted at these events—such as pigs and large quantities of root vegetables—canned corned beef is a processed food high in saturated fat, salt and cholesterol (a type of fat that clogs arteries). These are all things that contribute to disproportionately high incidences of diabetes and heart disease in Pacific Island populations as diets formerly high in locally grown fruits and vegetables, seafood, coconut milk and flesh, give way to cheap, imported foodstuffs.

So Tuffery’s sculpture is impossible to separate from the ceremonies at which brightly colored tins of corned beef now figure in large quantities. But these links to traditional economic exchanges and population health only tell part of the story. Pisupo Lua Afe also critiques serious issues of ecological health and food sovereignty. Tuffery is interested in the introduction of cattle to New Zealand and the Pacific Islands and how they impact negatively on the plants, landscapes and waterways of these countries, as well as how industrialized approaches to farming disrupt traditional food production.

Michel Tuffery, Pisupo Lua Afe (Corned Beef 2000), 1994, flattened cans of corned beef (Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Collection) ©Michael Tuffery

Look at Pisupo Lua Afe. It’s literally a “tinned bull”—solid, hard-edged and weighty. Having a real cow has a visual softness suggested by its movements, eyes and coat, Tuffery’s tin cans and rivets—overlapping like large metal scales—better convey the capacity of beef and dairy cattle to destroy fragile island eco-systems. Look closer—single out just one flattened can. Think about all the cans that were emptied to make Pisupo Lua Afe. Then think about all the cans that are emptied and discarded in the Pacific Islands each year. Tuffery is gesturing rather obviously towards the challenge of rubbish disposal in Island economies where creative “upcycling” of materials into new objects is often more common than the civic recycling regimes of larger cities and countries (upcycling refers to reusing discarded objects to create a product of a higher value). What use is there for thousands of empty tin cans? And what use are foods that cause ill health, damage the environment, and take up large swathes of land formerly used to grow healthier, indigenous foods? Especially when the Pacific Island nations under Tuffery’s scrutiny are recipients of some of the worst products of such agricultural farming: fatty lamb flaps and turkey tails, and tinned corned beef.

Food sovereignty

Food sovereignty (sometimes called food security) is a great lens through which to view the various threads of traditional economic exchanges, population health, environmental degradation and industrialized food production introduced so far. Food sovereignty is the right of a nation and its peoples to decide who controls how, where and by whom their food is to be produced, and what that food will be. For Indigenous peoples in the Pacific, food and the environment are sacred gifts. There cannot be food sovereignty without control over food production and ownership, and without appropriate care of the environment.

Alongside Pisupo Lua Afe and his other tin can bulls, Tuffery has produced many artworks that address challenges to food sovereignty and the continued exploitation of Pacific Island resources, including the taro leaf blight epidemic in Samoa in 1993, and drift net fishing that is depleting fish stocks. For example, he’s made fish tin sculptures, like his “tinned bull,” which upcycle cans that hold another “staple” food in the Pacific: tinned mackerel. Tuffery made two of these for an exhibition called Le Folauga , shown in Auckland, New Zealand in 2007, which are now in the collection of the Auckland War Memorial Museum.

![Michael Tuffery, Asiasi [Yellowfin] II (2000) , fish cans, copper, aluminum and polyurethane, 60 x 250 x 100 cm (Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Collection) © Michael Tuffery](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Michel_tuna_L.jpg)

Michael Tuffery, Asiasi [Yellowfin] II (2000) , fish cans, copper, aluminum and polyurethane, 60 x 250 x 100 cm (Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Collection) © Michael Tuffery

Le Saosao Lapo’a and Asiasi I reflect on the ironic and irreversible impact that over-fishing and exploitation of the Pacific’s natural resources has wrought on the traditional Pacific lifestyle. This includes changing virtually overnight the dietary habits of generations.

Is it co-incidental that significantly increasing health and dietary problems amongst Pacific Islanders has occurred during the same period that their premium fisheries catches are exported? And at the same time locals have experienced explosive growth of canned & other imported products flooding into the Pacific?

Tuffery states the aims of his works very clearly. His fish tin sculptures are perhaps even more interesting and evocative because they are also functional fish-smokers used to cure and preserve fish. They have been used in this way at his exhibition openings, bringing a smoky, wood- and fish-scented haze to the gallery experience.

Firebreathing bulls?

Tuffery has also brought his “tinned beef” bulls to smoky life in various performative installations throughout the world, by installing fireworks inside their heads to give them the appearance of breathing fire. Mounted on castors with their necks articulated so their heads can be turned, he has staged bullfights with his fire breathing monsters, accompanied by drummers and groups of human performers issuing fierce challenges. But these performances have not been restricted to the sanctuary of the white walled gallery—these were performed outdoors, on city streets, to reach a community that might not otherwise come into the gallery to encounter his work.