Elizabeth Catlett, Invisible Man, Riverside Park, New York, 2003, bronze and granite, 457 x 225 cm (photo: Studio Museum in Harlem)

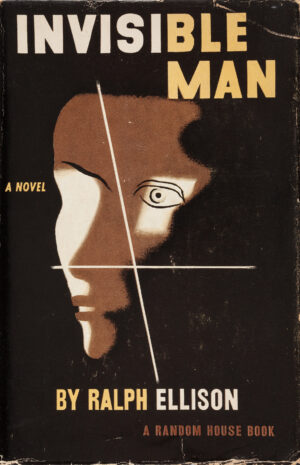

A strikingly simple object is displayed on a traffic island at the intersection of West 150th Street and Riverside Drive in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood. A thick bronze panel fifteen feet high, ten feet wide, and weighing five thousand pounds stands upright, with a large silhouette of a walking man cut through its mass. It is a public sculpture by Elizabeth Catlett produced in 2003, titled Invisible Man. Celebrating the African American novelist Ralph Ellison (who wrote a novel with that title), the piece also testifies to the culmination of Catlett’s lifelong artistic commitment to the struggles of Black Americans.

Civil rights

While Elizabeth Catlett lived much of her life in Mexico, her connection to the Civil Rights movement in the United States and her belief in the ideological role of art constitute the core of her work. Trained as a printmaker and sculptor, Catlett pursued a teaching career first in New Orleans and later in New York before traveling to Mexico in 1946 to work with the printmakers’ collective Taller de Gráfica Popular (People’s Graphic Workshop; TGP) on a Rosenwald Fund Fellowship. She eventually married the artist Francisco Mora and settled in Mexico. While she became intimately involved in TGP’s activist role in Mexico, the print series The Black Woman, done in 1946–47, demonstrates her preoccupation with the history and struggles of Black women in the United States.

Elizabeth Catlett, Homage to My Young Black Sisters, 1968, cedar, 172.7 x 30.5 x 30.5 cm (private collection)

Catlett became a Mexican citizen in 1962 to bypass the Mexican law prohibiting political involvement of foreign nationals. TGP’s socialist, anti-imperialist, and anti-fascist ideology and her dedication to these ideals soon alarmed the American government in that early phase of the Cold War. She was declared an “undesirable alien” by the U.S. State Department and was barred from entering the United States until 1971.

Disenchanted by what was perceived as the limitations of the mainstream Civil Rights movement, the Black Power movement emerged in the mid-sixties as an alternative force led by activists of a younger generation. The Black Panther Party, founded in 1966, asserted Black American identity and aggressively criticized capitalist oppression and systemic racism. The Black Arts Movement (BAM), which overtly addressed racial, economic, and gender oppression, was forged by artists sympathetic to this militant political position. Catlett lent her unequivocal support to the movement from abroad by producing prints and sculptures, such as the wood sculpture Homage to My Young Black Sisters in 1968, and the lithograph Negro es Bello II in the following year.

Invisible Man was produced immediately after Catlett’s American citizenship was reinstated in 2002 (though she chose to remain in Mexico for the last decade of her life). An homage to Ralph Ellison, the work shares the title of his iconic novel. The author’s Memorial Committee, in collaboration with Riverside Park Conservancy, chose the installation site in the neighborhood where Ellison lived until his death in 1994.

Homage to Ralph Ellison

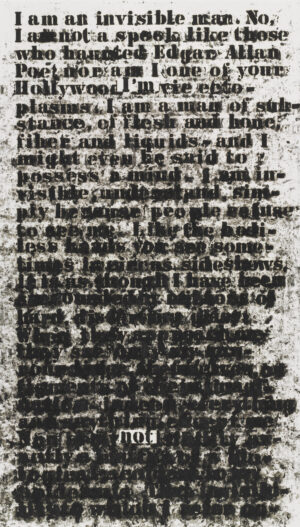

Invisible Man is regarded as the first of its genre to offer an African American perspective on racism and exclusion in American society. The male protagonist, a nameless, metaphorical individual who narrates in the first person, lives in a secluded part of a basement in a white-only building in New York. He struggles with his own identity in the face of society’s refusal to acknowledge his existence because of his race. “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me,” says the man in the novel’s opening paragraph. “When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination—indeed, everything and anything except me.” It is only the 1,369 lightbulbs illuminating his shelter that make his Blackness visible. Throughout his account, the narrator examines the complexities of America’s systemic inequity based on race, such as the hyper-visibility of a Black man in public (especially in a white setting) that paradoxically makes him invisible as a legitimate member of society.

Catlett’s sculpture powerfully articulates this paradox in its stark simplicity. While its verticality, patinated metal surface, monumental scale, and its location in a traffic circle make it unavoidably visible, the silhouette of the striding man within it remains an absence, merely a human contour devoid of any singular identity. Yet Catlett also subverts the paradox. While Ellison’s protagonist is made invisible by society, it is precisely the environment of the park that makes Catlett’s character clearly visible. His appearance becomes concrete against a variety of backdrops: foliage, buildings, the sky, or combinations of these. What is more, with its sides facing the east and the west, the bronze surface is illuminated on one side at dawn and on the other at dusk. Such temporal variations of light, combined with the seasonal changes in nature and the viewer’s vantage, offer the walking man in multiple, shifting personae and embrace him as an integral part of that urban setting.

Elizabeth Catlett, Invisible Man, Riverside Park, New York, 2003, bronze and granite, 457 x 225 x 15 cm (photo: Riverside Park Conservancy)

Multiple sources

Catlett admitted that though she had always wanted to pursue abstraction, she chose a type of social realist style which she absorbed from the Mexican muralist movement for her drawings and prints through much of her career because she was committed to making images of oppression and resistance accessible to common people. In sculpture, however, she combined her realist strategy with forms and motifs drawn from multiple sources, including African and Pre-Columbian art, and blended them with aspects of modern sculpture. The prominent negative spaces in the polished upper and lower torsos of Homage to My Young Black Sisters, for example, are as much reminiscent of African masks as of the sculptures of British artists Henry Moore and Barabara Hepworth (both of Catlett’s generation) that address the role of voids on solid surfaces. As a result, political content in this piece is delivered via a quasi-abstract human figure with impeccable formal balance between positive and negative spaces. It seems such creative experiments in form and composition helped Catlett resolve the challenge of representing invisibility in solid metal in the New York project. Previously explored for its formal possibilities, the interactions between solids and voids are employed here in the service of content. The work can be seen as a notable reconciliation between abstraction and realism, where a realistic void is contained within a solid and seemingly minimal object.

Glenn Ligon, Untitled (I am an invisible man), 1991, oilstick on paper, 76.2 x 43.8 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Elizabeth Catlett is neither the only nor the first artist to work on the theme of Ralph Ellison’s award-winning novel. Several others—most of them Black Americans—have embraced it to offer their own interpretations of the social invisibility of Black individuality in America in a range of mediums: Gordon Parks (for example Invisible Man Retreat, Harlem, New York, 1952); Kerry James Marshall (Invisible Man, 1986); Glenn Ligon (Untitled—I Am an Invisible Man, 1991); Ming Smith (Invisible Man, Somewhere, Everywhere, 1991); Jack Whitten (Black Monolith II—for Ralph Ellison, 1994); and the Canadian photo-based artist Jeff Wall (After ‘Invisible Man’ by Ralph Ellison, the Prologue, 1999–2000). But unlike these projects, Catlett’s work—the latest in this line of tributes to Ellison—is a free-standing sculpture and a monumental public piece. She empowers Blackness, which was the goal of her creative practice all along, by melding the walking man with his surroundings; like when, at the end of the novel, Ellison’s man decides to emerge from his self-imposed subterranean existence and enter society. This transition makes him Catlett’s protagonist as much as Ellison’s.

Additional resources

Watch a video about Ralph Ellison, Gordon Parks, and Harlem

View Catlett’s print series The Black Woman at the Museum of Modern Art

Mark Godfrey, editor, Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power (New York: D.A.P. and Tate Modern, 2017).

Melanie Herzog, Elizabeth Catlett: An American Artist in Mexico (St. Louis: University of Washington Press, 2005).