Every city contains signs and fragments of its hidden past. Every street contains layers of histories partially erased yet still perceptible to those who search for their traces. For example, there’s the inscription on a cornerstone that hints at the original purpose of a building, the single Victorian house on the block that has somehow survived decades of civic “revitalization,” or the peculiar architecture of a restaurant that betrays its former life as a silent movie theater. Sometimes if you squint hard enough and look high enough you can perceive the faint remnants of a painted advertisement still clinging to an exterior brick wall after decades of exposure to the elements.

But preservation is hardly neutral

In Los Angeles, where growth, development, displacement, and gentrification proceed at an often dizzying pace, the layers accumulate rapidly. Inevitably things are lost and new structures are erected on their rubble. Constant transformation seems to be part of L.A.’s civic identity since it became a proper city in the 1920s. Of course, preservation efforts have also been part of this transformation. But preservation is hardly neutral; for every building protected and restored, there are many more demolished or left to deteriorate. Not surprisingly, preservation decisions are sometimes based on how the city’s history can be productively “used” in the present. In Los Angeles, perhaps there is no better example than Olvera Street, a fanciful reconstruction of the city’s Mexican origins built in the 1930s, just as Los Angeles emerged as a modern metropolis. While honoring a selective version of the past, the primary purpose of the project was to attract tourism. Efforts to preserve buildings along Broadway, including movie theaters, was initially driven by developers’ interest in tying preservation to a more profitable, revitalized downtown.

Not surprisingly, this preservation logic typically excludes sites, buildings, murals, and neighborhoods regarded as marginal to the city’s historical identity or unlikely to generate revenue in the future. For a multiethnic metropolis like Los Angeles, these exclusions can all but erase from the landscape the traces of the city’s queer, Indigenous, immigrant, Black, working class, Asian, and Latinx past. But traces remain nonetheless. And they are indeed perceptible to those who seek them out, to those who chose to work against Los Angeles’s “history of forgetting,” as historian Norman Klein has succinctly phrased it.

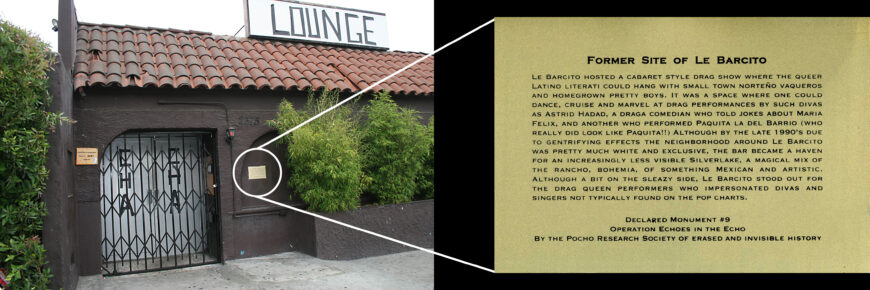

Sandra de la Loza and Pocho Research Society, Le Barcito, plaque and site view from Echoes en el Echo, 2007, silkscreen on sheet metal, 7 x 12 inches © Sandra de la Loza

Excavating history

Sandra de la Loza is one of those people. Her artistic practice is dedicated to thinking differently about urban space, to excavating forgotten fragments of the city’s past, to memorializing the presence and histories too frequently buried beneath layers of development or neglect. In my conversations with De la Loza, I have always been struck by her description of her work as “activating history.” It is not that we can’t see the original building, for instance, but that no one has bothered to explain how it was used. Her work with/as the Pocho Research Society of Erased and Invisible History (a group of “artists, activists, and rasquache historians” founded in 2002) places unofficial monument markers on overlooked historical sites. By doing so, the group activates urban space, compelling us to think in new ways about the streets we traverse, gesturing toward the multitude of marginalized histories that still peek through cracks of a rapidly transforming city with a short and often Eurocentric memory.

Working collaboratively with other artists as the Pocho Research Society, for her project Echoes en el Echo: A Series of Interventions about Memory, Place, and Gentrification, De la Loza placed memorial plaques on sites that were once bars or nightclubs serving a queer Latinx clientele. While so many existing monuments and historical markers commemorate politicians (some enslavers) and celebrate war victories, “queer cultural histories are particularly erased,” according to De la Loza. Her efforts focused primarily on the neighborhoods of Silver Lake and Echo Park, just west of downtown. Both were once diverse, working-class neighborhoods with establishments that catered to people of color. In the 21st century, both neighborhoods have been gentrified almost beyond recognition; the working-class Latinxs that used to call the neighborhood home have been increasingly displaced by high rents and a steady stream of more affluent, white newcomers.

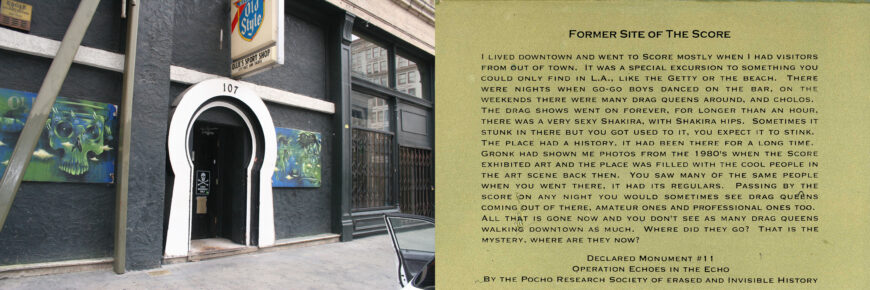

Sandra de la Loza and Pocho Research Society, Score Bar, plaque and site view from Echoes en el Echo, 2007, silkscreen on sheet metal, 7 x 12 inches © Sandra de la Loza

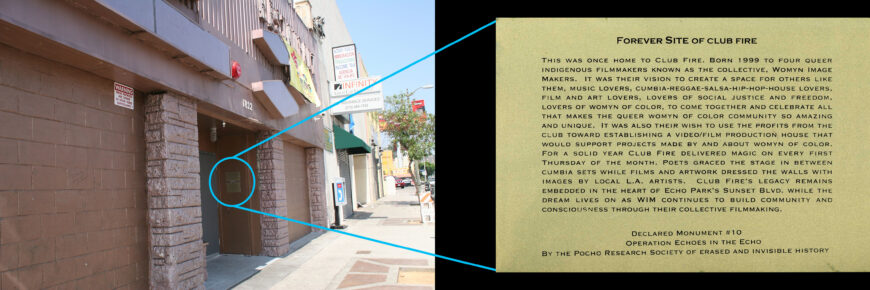

In the dead of night, De la Loza affixed unofficial historical markers to several defunct bars: Le Barcito in Silverlake, Klub Fantasy in Echo Park, Club Fire, and the Score Bar. As bronze plaques affixed to walls, they very much resemble official historical markers. But their presence is almost always temporary; the current occupants of those spaces typically remove them immediately. The pieces are, in some ways, a cross between a commemorative plaque and illegal street art. The text of these markers were written by queer artists and authors who frequented those establishments, including Ramón García, Womyn Image Makers, Ricardo Bracho, and Raquel Gutiérrez. De la Loza would then return the next day to take photographs of the markers before they were inevitably destroyed or removed as renewed acts of historical erasure. Not only were these markers unofficial, they were ephemeral, now existing only through documentation like the Pocho Research Society’s book, Field Guide to L.A.

What did these markers commemorate, exactly? In the case of Le Barcito, it was a vibrant space that hosted drag performances and attracted a diverse clientele. In the words of García that adorn the plaque, the space (now the Cha Cha) was “A magical mix of the rancho, bohemia, of something Mexican and artistic.” In the case of Club Fire, it was a vibrant cultural space founded to support a media production facility for women of color. Located downtown, the Score Bar hosted drag nights and also once served as an exhibition space for a generation of queer artists including Gronk, Joey Terrill, and Tomata du Plenty.

Sandra de la Loza and Pocho Research Society, Club Fire, plaque and site view from Echoes en el Echo, 2007, silkscreen on sheet metal, 7 x 12 inches © Sandra De la Loza

Critical questions

The collaborative nature of the project brought together a cohort of queer artists to excavate the memory of these spaces in the face of the city’s propensity to forget, whitewash, and gentrify. The plaques also eschew the deceptively “neutral” delivery of most historical plaques to instead offer poetic evocations and impressionistic recollections of sweating on the dance floor, finding queer community, and (in Bracho’s terms) “scoring” at the Score. They effectively “activate” (to cite De la Loza’s term) a rich history of queer conviviality and creativity for new generations, laying the groundwork for exhibitions like the 2017 Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. In this regard, Echoes en el Echo is an apt example of interventionist art or what is often referred to as “social practice.” Rather than depicting urban space, for instance, De la Loza’s plaques intervene directly in the urban environment, confronting pedestrians and bar patrons with erased histories. And as social practice, her work aspires to alter social relations, to foster dialogue, and to transform the way Los Angeles history is archived and narrated. Both concepts—intervention and social practice—take as their “canvas” the physical environment of the city and the ways in which we perceive it. Encountering one of these plaques on the street, for instance, may alter our understanding of a neighborhood, provoke us to seek out works by the poets involved, or inspire us to do further research, opening a door to a world of erased histories and queer artistic practice. It may also empower us to follow the example of the Pocho Research Society by producing our own “guerilla” histories, exerting a degree of control over urban space and our relationship to it.

More than just nostalgia or commemoration, De la Loza’s work confronts us with critical questions about history, urban space, queer culture, and artistic practice. Rather than an enduring object of art, the ephemeral project gathers community anew, instigates a conversation, and creates an alternative historical record. The press release for Echoes en el Echo poses provocative questions that, beyond this particular project, motivated the work of the Pocho Research Society: “How and who defines a space? Is space defined by its present incarnations or does its past ruthlessly resurface like dust in unswept corners?” These questions are central to the rapid transformation of our cities in the 21st century, which is too often premised on inequality, displacement, and forgetting. De la Loza reminds us to tend to the dusty corners, the traces, the memories, and the margins where other histories and experiences might still call out to us.

This essay is part of Smarthistory’s Latinx Futures project and was made possible thanks to support from the Terra Foundation for American Art.