Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, England, begun 1220. Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re in Salisbury Cathedral in southwest England. This is an early Gothic church.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:10] In England, we divide the Gothic into three periods: the Early Gothic, the Decorated Gothic, and Perpendicular. Here we’re at an early moment in the development of the Gothic style here in England. In France, you could imagine the great cathedral of Amiens being built at the same time, but this is so clearly not a French cathedral.

Dr. Zucker: [0:31] This is a typical English cathedral in its layout and in its scale. It’s enormous, but it doesn’t reach the heights of the French cathedrals during the high Gothic period. That’s not to say this is a low ceiling. The volt towers above us and so it really is just lower in comparison.

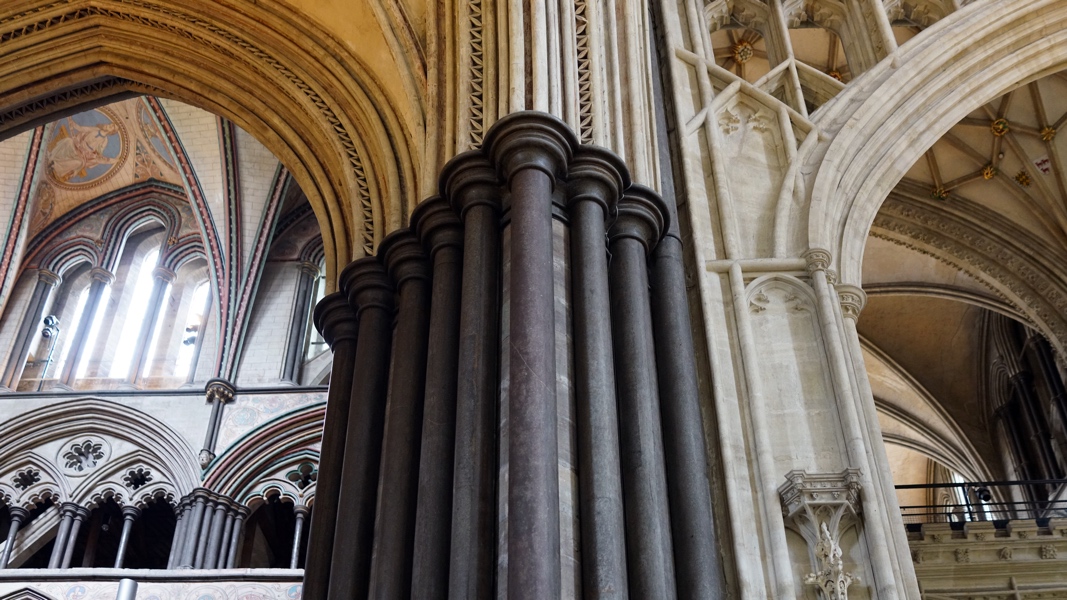

Dr. Harris: [0:48] One of the ways that the architect emphasized that horizontality is by the use of a stone that we call Purbeck marble, and it’s this dark grayish-brown color and it’s used to articulate some of the horizontal members that draw our eye down.

Dr. Zucker: [1:04] You can see that especially if you look at the interior elevation above the nave arcade on the second level which we call the gallery.

Dr. Harris: [1:11] We see typical Gothic decorative motifs like quatrefoils and pointed arches, but in Purbeck, we see these bundled columns that have a depth and energy to them.

Dr. Zucker: [1:21] They emphasize the linear; it’s as if the entire church is outlined with slender columnar forms.

Dr. Harris: [1:28] We have the slender columns in the knave that are surrounded by smaller columns that are slightly detached, but then the pointed arch itself is so deep with this rolled molding that emphasizes the depth of the wall.

Dr. Zucker: [1:43] We also see it in the dimensionality of the wide gallery and even above that in the depth of the clerestory where there’s a narrow passage between the exterior glass and the interior space of the nave.

Dr. Harris: [1:55] This was all once brightly painted so what we’re looking at is rolls of stone. Each roll would have been picked out in different colors and so it would have even seemed more veneer, I think.

[2:06] We should start perhaps by just noting that we have a typical Gothic elevation of a nave arcade with pointed arches and above that the gallery, and above that a clerestory, and then typical ribbed four-part groin vaults.

Dr. Zucker: [2:20] Salisbury Cathedral was built very quickly. The main part of the church was built within 38 years which means there’s a continuity, a kind of consistency. The cloister was added later and then the tower was raised higher and the spire was added.

Dr. Harris: [2:34] Because that tower and spire is so heavy, the architects added strainer archers to help support that weight.

Dr. Zucker: [2:40] Not only are English cathedrals known for these very long plans, in fact, so long that they often have at the east end an additional choir known as a retrochoir.

Dr. Harris: [2:51] And you have a second transept.

Dr. Zucker: [2:53] Which allows for additional chapels which are often not found along the nave.

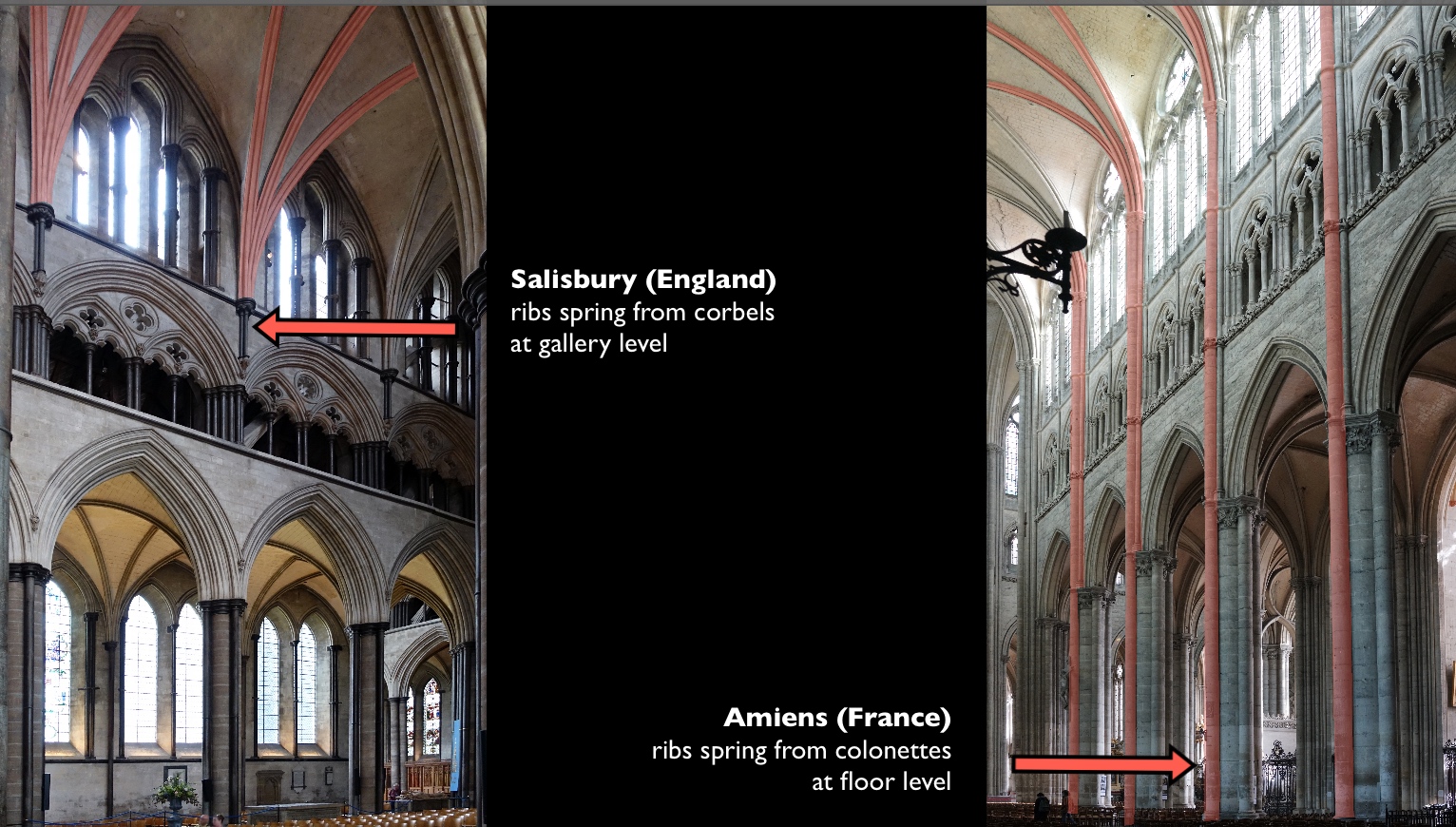

Dr. Harris: [2:57] One of the other ways that the architect emphasized the horizontal, as opposed to the vertical, is that we don’t have colonettes that rise from the floor to articulate the ribbed groin vault. Instead, the ribs of the vault spring from these corbels.

[3:12] What’s fun is right at the base of each of those is a sculpted head.

Dr. Zucker: [3:17] It emphasizes this interest in the decorative that is such a characteristic of English cathedral architecture.

Dr. Harris: [3:23] I’m looking too at the gallery level where the two pointed arches meet and these decorative ball flowers.

Dr. Zucker: [3:30] Like all English churches, this one has gone through substantial changes. The choir screen that separated the church in two, the laypeople in the west end of the church, from the most sacred part, the east end.

Dr. Harris: [3:42] We’re lucky that a piece of that choir screen survives. It’s beautifully decorated with painted angels in the spandrels and gabled niches that would have once held statues.

Dr. Zucker: [3:52] And some wonderful examples of ball flowers. You had mentioned that this church was originally painted in different colors to articulate the architecture.

[4:00] In the vaults high above us, above the choir, in the eastern section of the church, there were roundels of paintings that historians believe reflected the liturgy that was performed in the church below.

Dr. Harris: [4:11] Those original Gothic paintings were covered over with whitewash, but we know that they included images of prophets and a sybil of angels of Christ in majesty.

[4:22] This church is filled with so much 19th-century stained glass. Originally, most of the stained glass was grisaille, that is, tones of gray. We can see some of that in the south transepts.

[4:33] Much of the Victorian stained glass does include biblical stories and figures. There are two especially beautiful windows by the great Victorian artist Edward Burne-Jones. These are two lancet windows that are occupied mostly by these interlacing vines and leaves.

Dr. Zucker: [4:50] The four angels are brilliantly colored. One is green with these incredibly elaborate yellow wings. We have a brilliant blue angel, and both of those angels hold staffs. On the right, we have two angels that hold harps and are both in brilliant red.

Dr. Harris: [5:04] It’s lovely to see these Burne-Jones windows here at Salisbury Cathedral.

Dr. Zucker: [5:08] We’ve walked outside. The outside is so different from French Gothic cathedrals of the same period. At Amiens, begun the same year as this church, you have a massive porch with deep portals that draw you in.

Dr. Harris: [5:21] Here we see three doorways.

Dr. Zucker: [5:23] I’m struck by how modestly scaled those doorways are. Here, the west front is larger than the church behind it.

Dr. Harris: [5:31] Now, the figurative sculpture that we’re seeing today in the niches, the vast majority of it is modern. It’s from the 19th century and we’re not even sure how much sculpture was originally here in the 13th century when the church was built.

[5:44] If you look closely at the screen of figures just above the central doorway, there are small openings and there’s a passageway behind this that we believe was used for people to sing from during Liturgical festivals that took place outside the west front of the church.

Dr. Zucker: [6:00] The conceit would be that the sculpted figures that we see were actually singing to the crowd below.

[6:06] Salisbury Cathedral, this early English Gothic style church will have an enormous impact on buildings that are constructed later as the English Gothic style develops. Looking at the church, centered in this large close, the church’s grounds, it’s impossible not to think of the early 19th-century painter John Constable and his multiple paintings of this church.

Dr. Harris: [6:29] Well, the church does sit in a field and rises steeply up from that, and Constable gives us that impression so well in the spire that reaches up towards the heavens and the sense of man’s yearning for the divine is very much present.

[6:44] [music]

The biggest and the highest

There are so many superlatives consorting with the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Salisbury: it has the tallest spire in Britain (404 feet); it houses the best preserved of the four surviving original copies of the Magna Carta (1215); it has the oldest working clock in Europe (1386); it has the largest cathedral cloisters and cathedral close (grounds) in Britain; the choir (or quire) stalls are the largest and earliest complete set in Britain; the vault is the highest in Britain. Bigger, better, best—and built in a mere 38 years, roughly from 1220 to 1258, which is a pretty short construction schedule for a large stone building made without motorized equipment.

One factor that enabled Salisbury Cathedral to become so extraordinary is that it was the first major cathedral to be built on an unobstructed site. The architect and clerics were able to conceive a design and lay it out exactly as they wanted. Construction was carried out in one campaign, giving the complex a cohesive motif and singular identity. The cloisters were started as a purely decorative feature only five years after the cathedral building was completed, with shapes, patterns, and materials that copy those of the cathedral interior.

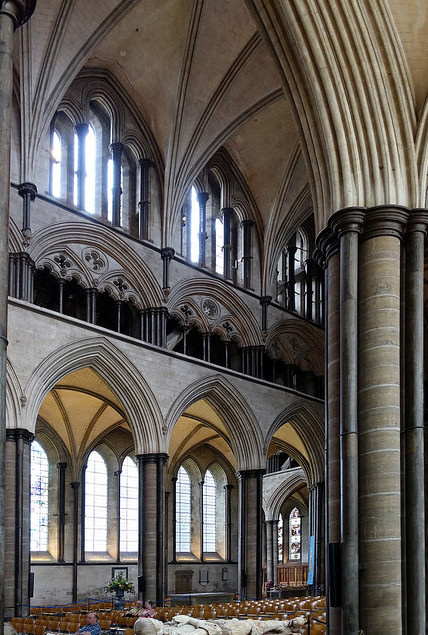

Looking west from the choir to the nave, Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, England, begun 1220, photo: Dr. Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Nave elevation, Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, England, begun 1220, photo: Dr. Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

It was an ideal opportunity in the development of Early English Gothic architecture, and Salisbury Cathedral made full use of the new techniques of this emerging style. Pointed arches and lancet shapes are everywhere, from the prominent west windows to the painted arches of the east end. The narrow piers of the cathedral were made of cut stone rather than rubble-filled drums, as in earlier buildings, which changed the method of distributing the structure’s weight and allowed for more light in the interior.

The piers are decorated with slender columns of dark gray Purbeck marble, which reappear in clusters and as stand-alone supports in the arches of the gallery, clerestory, and cloisters. The gallery and cloisters repeat the same patterns of plate tracery—basically stone cut-out shapes—of quatrefoils, cinquefoils, even hexafoils and octofoils. Proportions are uniform throughout.

One deviation from the typical Gothic style is the way the lower arcade level of the nave is cut off by a string course that runs between it and the gallery. In most churches of this period, the columns or piers stretch upwards in one form or another all the way to the ceiling or vault (see diagram below). Here at Salisbury the arcade is merely an arcade, and the effect is more like a layer cake with the upper tiers sitting on top of rather than extending from the lower level.

Comparison of the nave elevations of Salisbury Cathedral and Amiens Cathedral Nave elevation, photos: Dr. Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The tower and the spire

The original design called for a fairly ordinary square crossing tower of modest height. But in the early part of the 14th century, two stories were added to the tower, and then the pointed spire was added in 1330. The spire is the most readily identified feature of the cathedral and is visible for miles. However, the addition of this landmark tower and spire added over 6,000 tons of weight to the supporting structure. Because the building had not been engineered to carry the extra weight, additional buttressing was required internally and externally. The transepts now sport masonry girders, or strainer arches, to support the weight. Not surprisingly, the spire has never been straight and now tilts to the southeast by about 27 inches.

Scissor (strainer) arches in the east transept, Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, England, begun 1220, photo: Dr. Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Restorations

Over the centuries the cathedral has been subject to well-intentioned, but heavy-handed restorations by later architects such as James Wyatt and Sir George Gilbert Scott, who tried to conform the building to contemporary tastes. Therefore, the interior has lost some of its original decoration and furnishings, including stained glass and small chapels, and new things have been added. This is pretty typical, though, of a building that is several centuries old. Fortunately, the regularity and clean lines of the cathedral have not been tampered with. It is still refined, polished, and generally easy on the eye.

Purbeck colonettes at the crossing (transept), and to the left, gallery and clerestory moldings that have been repainted, Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, England, begun 1220, photo: Dr. Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Sunlight

Although it inspires the usual awe felt in such a grand and substantial building, and is as pretty as a wedding cake, it has had some criticism from art historians: Nikolaus Pevsner and Harry Batsford both disliked the west front, with its encrustation of statues and “variegated pettiness” (Batsford). John Ruskin, the Victorian art critic and writer, found the building “profound and gloomy.” Indeed, in gray weather, the monochromatic scheme of Chilmark stone and Purbeck marble is just gray upon gray.

The pictures, however, show the widely changing character of the neutral tones; sunlight transforms the building, and the visitor’s experience of it. This very quality is what made the Gothic style so revolutionary—the ability to get sunlight into a large building with massive stone walls. Windows are everywhere, and when the light streams through the clerestory arches and the enormous west window, the interior turns from drear gray to transcendent gold.