The 7th to 11th centuries: foundation, destruction and restoration

In the seventh century a set of monasteries was founded in the diocese of Rouen, in present-day northwestern France, under Saints Ouen (b. 641, d. 686), Wandrille (b. c. 600, d. 668) and Philibert (b. c. 617, d. 684). These abbeys, including Fontenelle, Jumièges and Saint-Ouen, rapidly became major spiritual and cultural centres under the Merovingian dynasty, which ruled in the territory similar to Roman Gaul.

Each established scriptoria for copying manuscripts and built up comprehensive libraries. However, from the mid-ninth century the region was devastated by Viking raids. Religious communities were sacked, and their possessions, including books, were scattered or destroyed. Few surviving Norman manuscripts from this period are known.

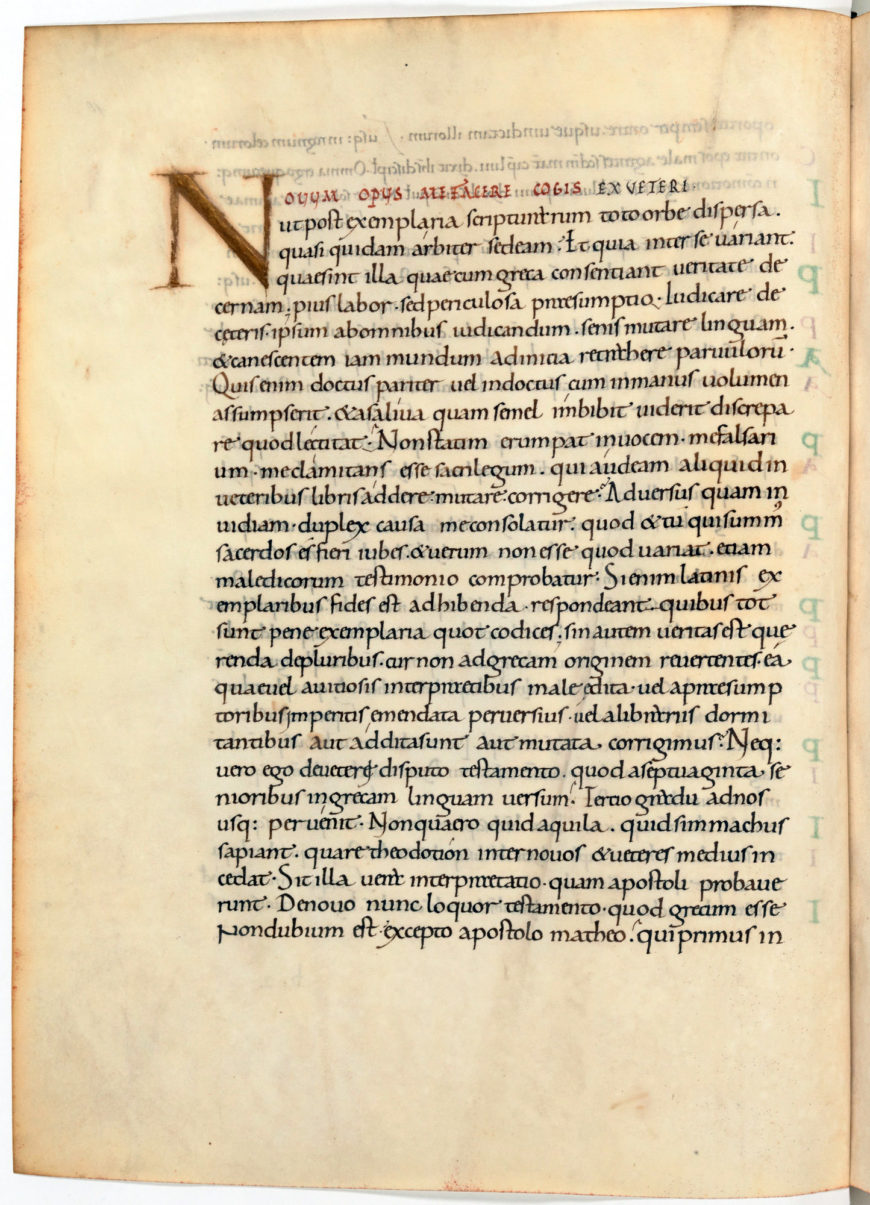

In 911, the Frankish king Charles the Simple (r. 898–923) granted the Scandinavian chieftain, Rollo (d. c. 927) possession of the lands Rollo had invaded in what is now Normandy (or The land of the “North men” (Normands)). Restoration of the religious infrastructure was slow under the new rulers: only six Merovingian abbeys had been re-established by the year 1000. The earliest surviving manuscripts, from the abbeys of Mont Saint-Michel, Jumièges and Fécamp, date from this period.

Monastic reforms in the 11th and 12th centuries

The new Norman nobility began to found religious institutions in much greater numbers during the 11th century, so that by 1100 there were close to 40 Benedictine abbeys (both male and female) in the region. Monasticism flourished under Richard II, Duke of Normandy (r. 996–1026), nicknamed ‘the father of all monks’.

Reformers were brought from other parts of France and Europe to build monasteries and introduce new liturgical practices. Religious orders such as the Cistercians and Premonstratensians founded houses and established new traditions of monasticism. At least 16 Norman abbeys had libraries, furnished with books made in their scriptoria. Many of these manuscripts have survived to the present day.

There were close ties between Normandy and England from the early 11th century. Queen Emma (b. c. 985, d. 1052), sister of Duke Richard II and consort of Kings Æthelred and then Cnut, was a benefactor of the abbey of the Trinity at Fécamp. She gave it luxury books like the Fécamp Gospels (now BnF, Latin 272), which includes initial letters written in red, green and gold.

English manuscripts and the Winchester style in Normandy

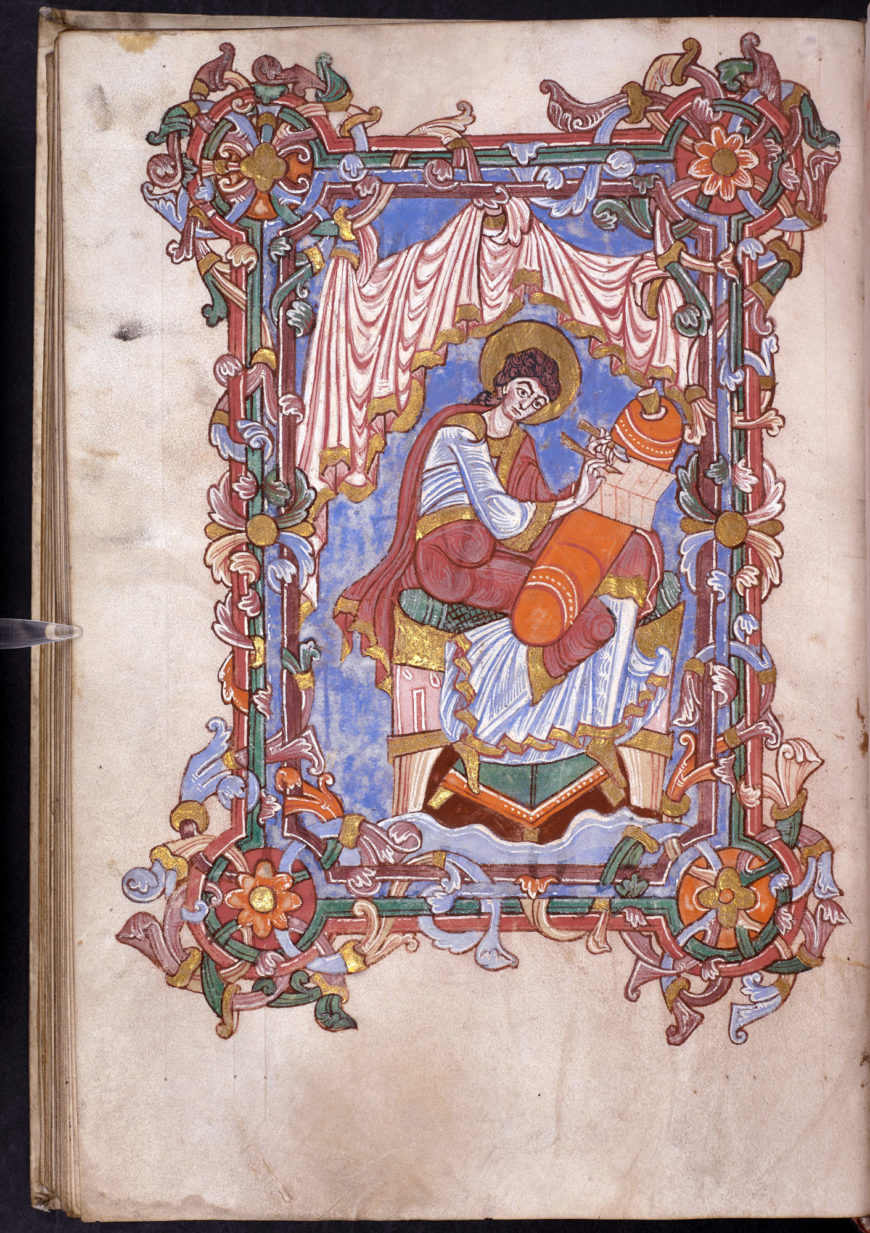

Ties between the two territories were strengthened under Edward the Confessor (r. 1042–1066), the eldest son of Emma and Æthelred, who had spent much of his youth at the court of Duke Richard II. The abbot of Jumièges, Robert Champart, became bishop of London in 1044 and Archbishop of Canterbury in 1051. Robert donated a splendid Sacramentary (containing the prayers recited by the priest during Mass) to his former monastery of Jumièges (now Rouen, Bibliothèque municipal, Y 6).

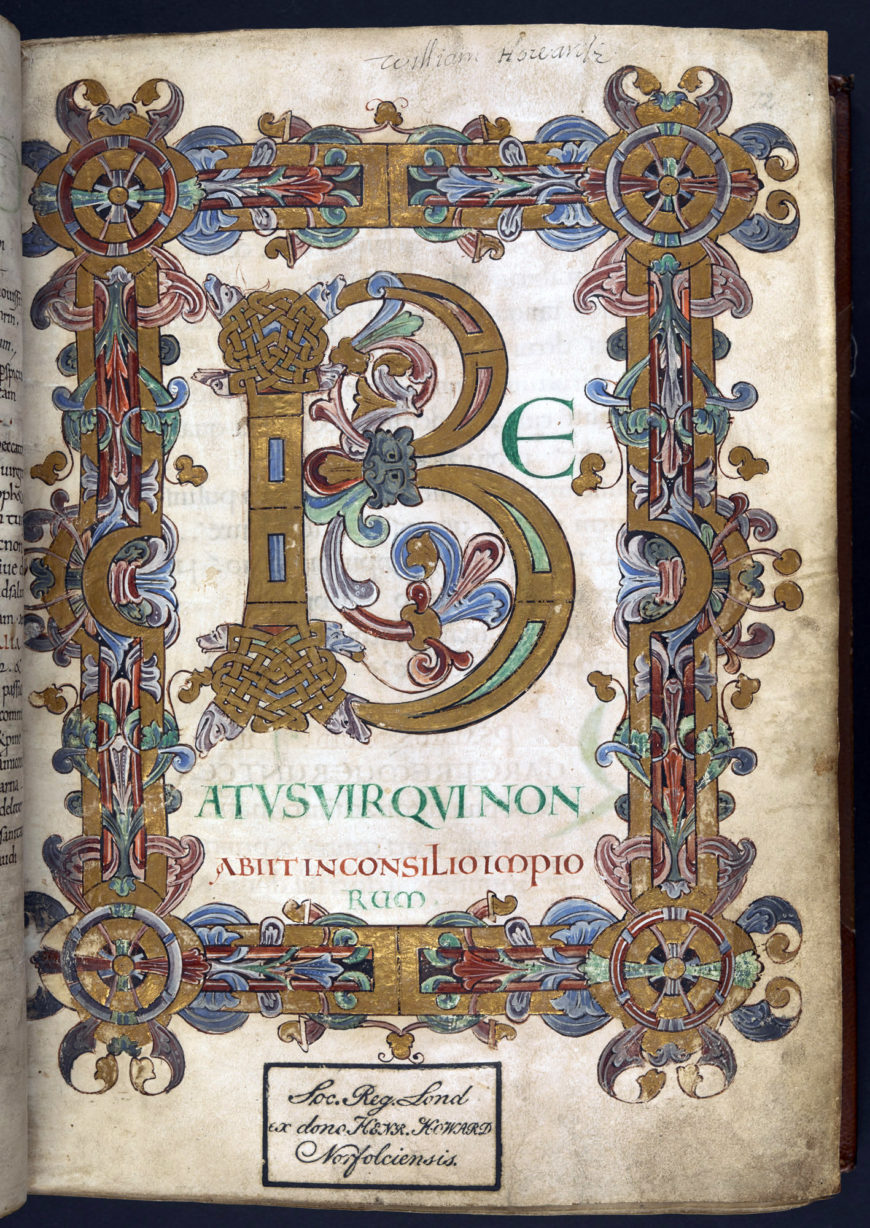

The manuscript is decorated in the late Anglo-Saxon ‘Winchester style’, with frames of painted foliage and animal heads, in a style similar to that found in a Psalter copied by Eadui Basan, a monk of Christ Church, Canterbury who is known to have been active between c. 1012 and c. 1023.

Illuminated initial ‘B'(eatus) and full border at the beginning of Psalm 1, in a manuscript copied at Christ Church, Canterbury, Eadui Psalter, 1st half of the 11th century–mid 12th century (British Library, Arundel MS 155, f. 12r)

The new institutions founded in Normandy needed books, and key works had to be sourced for their scribes to make copies. These exemplars were borrowed from as far afield as Dijon and Corbie. There is also substantial evidence of books being brought across the Channel to Normandy from monastic libraries in England.

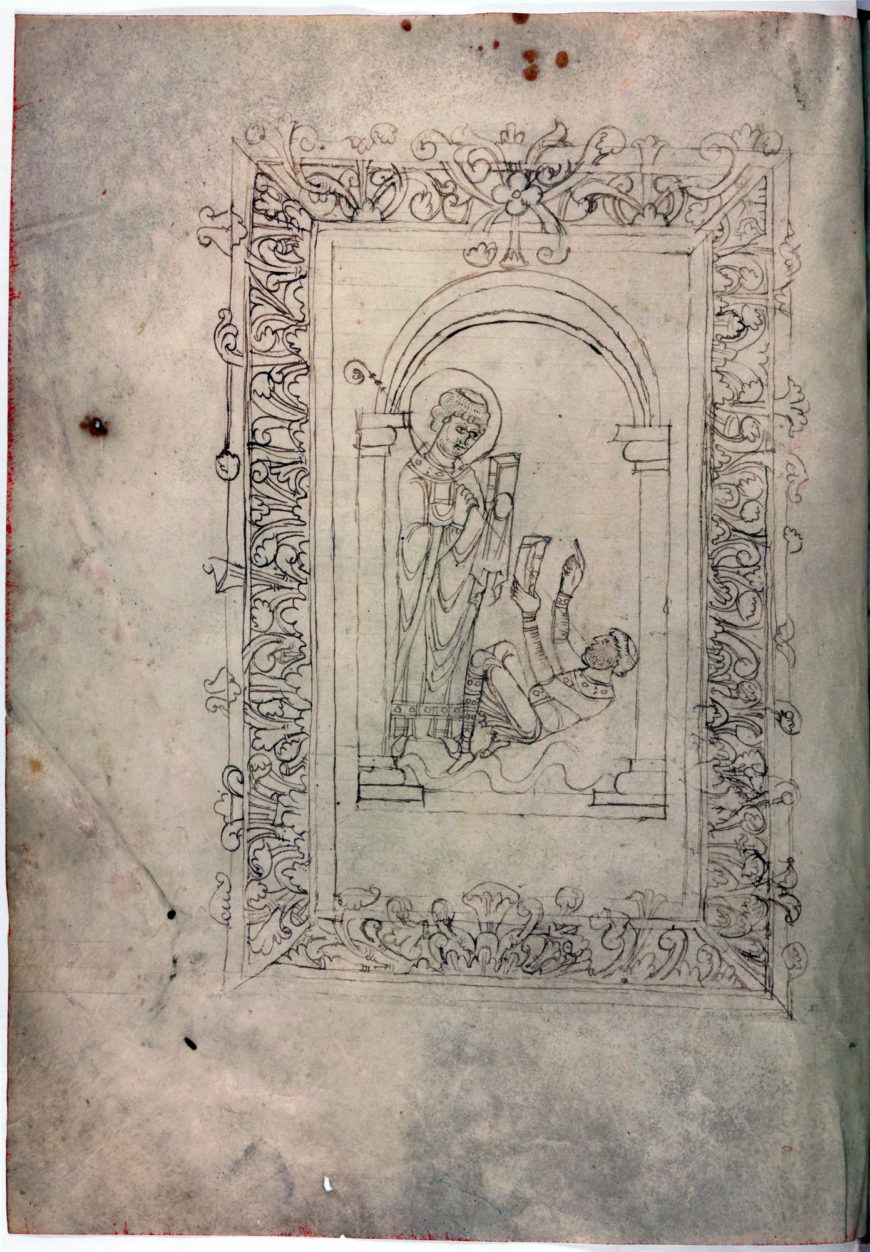

A framed pen-drawing of St Augustine attacking Faustus, St Augustine, Contra Faustum Manichaeum, mid-11th century (BnF, Latin 2079, f. 1v)

For example, manuscripts illuminated at Fécamp and Mont Saint-Michel under the supervision of the scribe Antonius (fl. c. 1060) show the influence of the Anglo-Saxon style on artists working at these two houses. The frontispiece from a Fécamp copy of St Augustine’s (b. 354, d. 430) work Contra Faustum Manichaeum (Against Faustus the Manichean) includes Winchester-style frames (BnF, Latin 2079). In the frontispiece the outline was drawn in ink, complete with an elaborate frame with stylised acanthus leaf decoration, but the page was left unpainted.

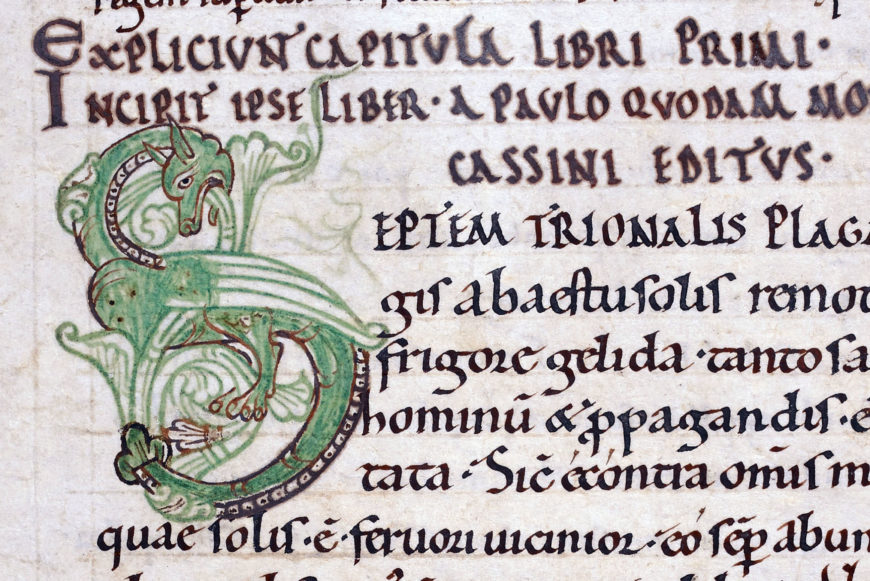

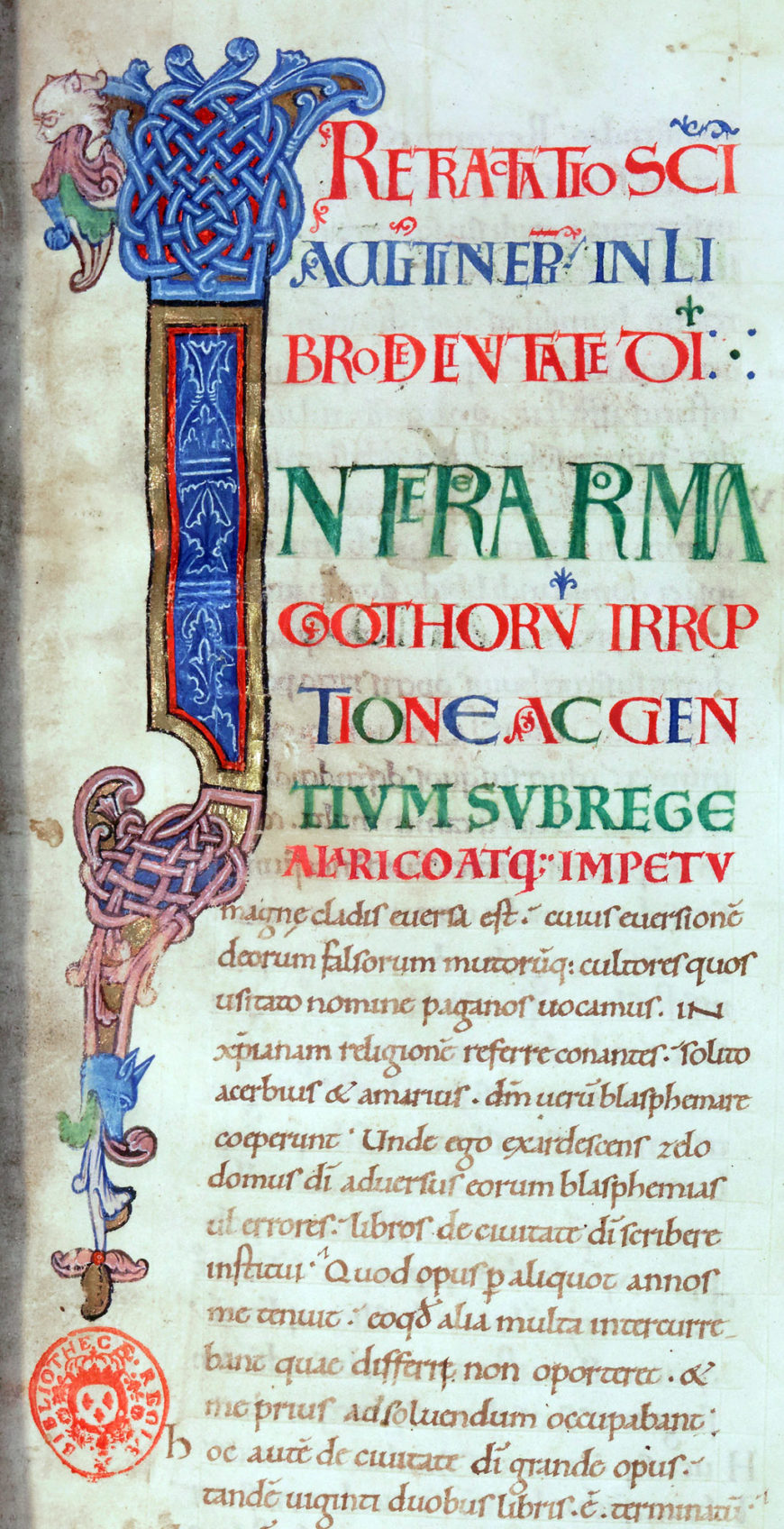

Interlace initial from the opening page of St Augustine’s De civitate Dei, c. 1060 (The City of God) (BnF, Latin 2055, f. 1r, detail)

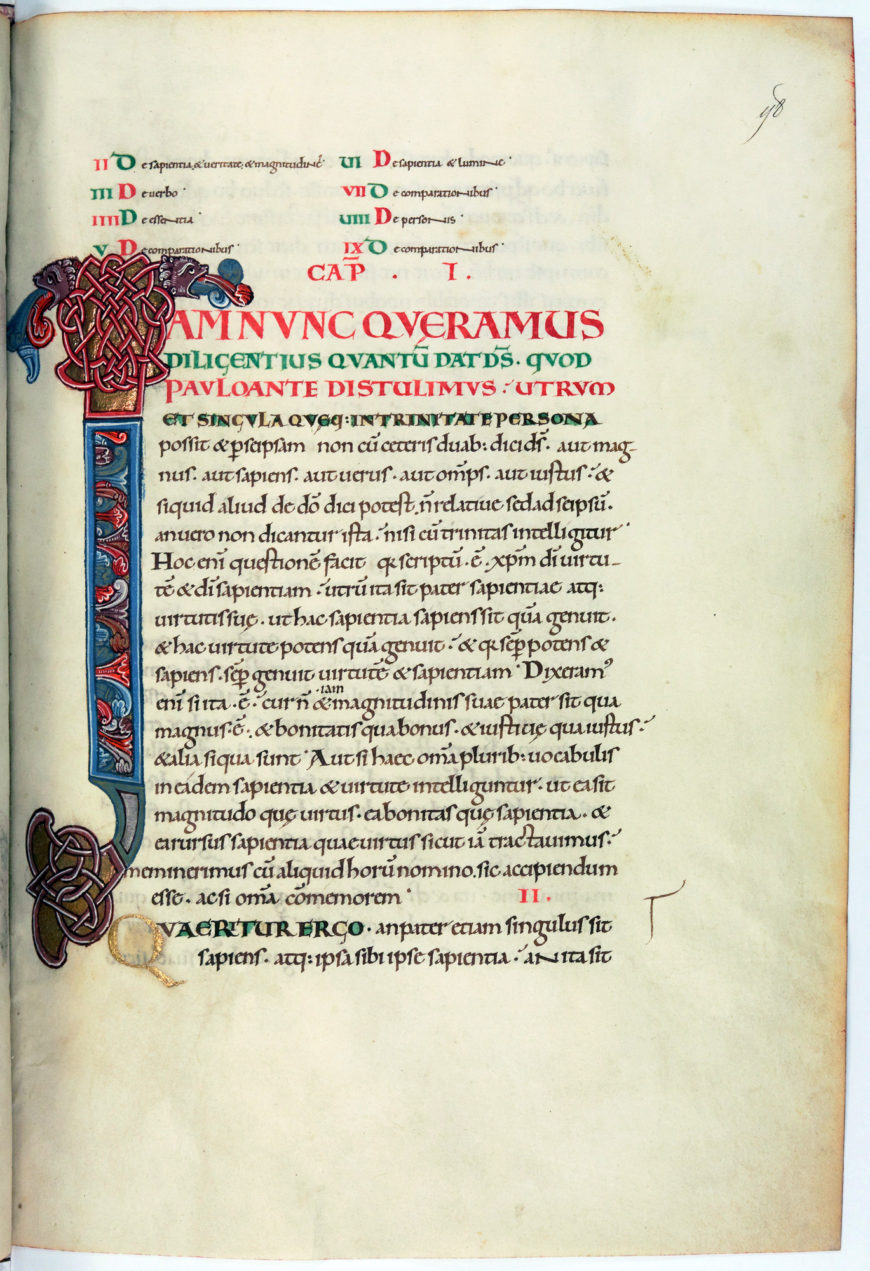

Two of St Augustine’s works were copied by the scribe Antonius himself and decorated in the Winchester style. The first manuscript contains De civitate Dei (the City of God), and the second contains De Trinitate (The Trinity). Both can be dated to between 1056 and 1065 (BnF, Latin 2055 and Latin 2088).

Interlace initial in a French copy of St Augustine’s De Trinitate (The Trinity), c. 1060 (BnF, Latin 2088, f. 78r)

English-style frames are also found in a number of luxury Gospel-books produced in Normandy between the last quarter of the 11th century and the first quarter of the 12th century. An example is a Gospel book from the abbey of Saint-Pierre de Préaux (British Library, Add MS 11850). This deluxe book features full-page portraits of the four Evangelists in rectangular frames in bright colours and gold, with foliate decoration.

The Norman Conquest

William, Duke of Normandy (‘the Conqueror’) was crowned king of England in 1066 (r. 1066–1087). Following his accession to the throne, a number of senior Norman clerics including Lanfranc of Bec (b. c. 1010, d. 1089) and Herbert Losinga of Fécamp (d. 1119) were appointed to key positions in the English Church. These churchmen brought manuscripts with them and also ordered books that were unavailable in England from their former monastic houses in Normandy. English handwriting in particular was influenced by the more angular Norman style.

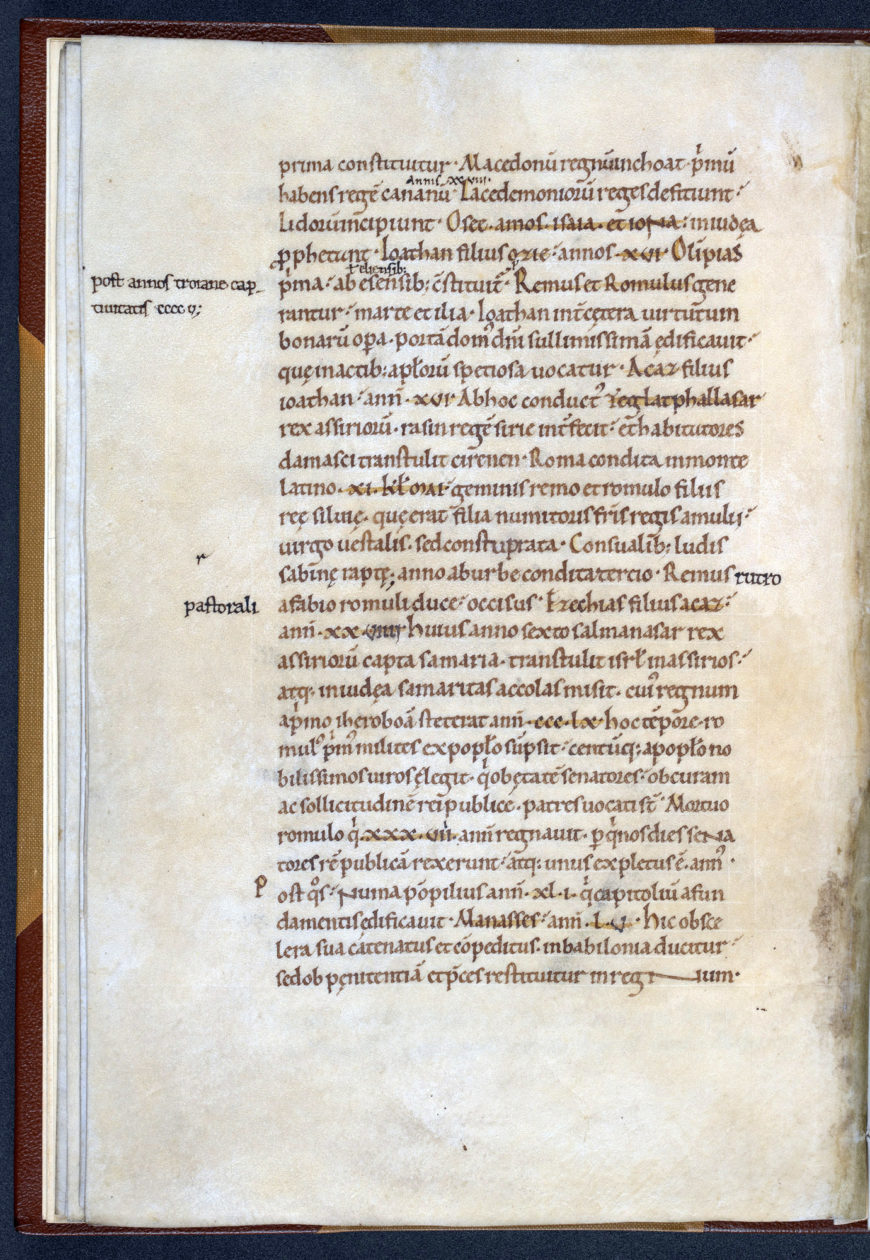

Text page with marginal notes from Ado de Vienne’s Chronicon, 4th quarter of the 11th century (Chronicle of the Six Ages of the World) (British Library, Royal MS 13 A XXIII, f. 16v)

For example, the Norman scribe Scollandus was previously based in Mont Saint-Michel. He became abbot of St Augustine’s abbey in Canterbury in 1072. Two manuscripts that he brought to Canterbury from Mont Saint-Michel are now in the British Library. One manuscript contains a chronicle written by Ado of Vienne (d. 874) together with a list of the dukes of Normandy (British Library, Royal MS 13 A XXIII). Additions and corrections have been made in the margins in a script characteristic of scribes working at St Augustine’s, Canterbury around 1100.

The second manuscript that Scollandus brought to Canterbury also features historical material (British Library, Royal MS 13 A XXII). The book contains the Historia Langobardorum (History of the Lombards) written by Paul the Deacon (b. c. 720, d. 799), followed by an excerpt from the chronicle of world history by Frechulf of Lisieux (d. c. 850). These texts are similar to models that were in the library at Mont Saint-Michel and the decoration is typical of manuscripts copied there.

These examples of artistic influence and circulation of books testify to the frequent exchanges across the Channel before and after 1066, as monks, scribes and artists travelled between monastic houses. These cultural exchanges contributed to the richness of manuscript production and decoration in both Normandy and England in the 11th century.