Theodora mosaic, 540s, San Vitale, Ravenna (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Justinian mosaic, 540s, San Vitale, Ravenna (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Empress Theodora

The famed imperial mosaics in the church of San Vitale in Ravenna depict the sixth-century Byzantine empress Theodora across from her husband, the emperor Justinian. Empress and emperor appear at the center of each scene, larger than the other figures to show their importance, bedecked in imperial purple, and sporting lavish crowns framed by golden haloes. They process with clergy, courtiers, and soldiers into a church (although neither Justinian nor Theodora ever actually entered San Vitale in Ravenna, which was located far to the west of the Byzantine capital of Constantinople).

While this mosaic of the empress and her retinue in San Vitale is the only certain visual depiction of Theodora, several written descriptions of Theodora survive. The challenge for us today is interpreting these texts, because they diverge significantly in their depiction of the empress.

The writings of Prokopios

The writings of Prokopios of Caesarea, a historian during the reign of Justinian and Theodora, are our main source for their reign. Prokopios wrote several works, such as Wars and Buildings, which cast Justinian and Theodora in a favorable light and circulated widely. But Prokopios also authored a text known as the Secret History, or Anekdota (literally “unpublished things”), which was not initially intended for wide circulation and which attacked the imperial couple.

Prokopios’s Secret History survived from the Byzantine era to today in just one manuscript copy, suggesting that it was not widely reproduced in the Byzantine period. But in our time, the Secret History has become Prokopios’s most popular work, and one of the most widely read primary sources from Byzantine history.

Detail of Theodora mosaic, 540s, San Vitale, Ravenna (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Comparing primary sources

Consider the following excerpts from primary sources, which illustrate how a writer or artist could depict the same subject in a positive or negative light. As you compare these depictions of Theodora, ask yourself why these texts and images were created, what details each work emphasizes, and possible agendas these works were created to serve.

Theodora’s physical appearance

The following two statements—both written by Prokopios—describe Theodora’s physical appearance. Such descriptions of a person’s outward appearance were especially loaded in the Byzantine Empire, where it was widely believed that physical beauty mirrored inner qualities such as virtue.

| The statue [of Theodora] was indeed beautiful, but still inferior to the beauty of the Empress; for to express her loveliness in words or to portray it in a statue would be, for a mere human being, altogether impossible.

Prokopios, Buildings I.xi.2–6 |

Now Theodora was fair of face and in general attractive in appearance, but short of stature and lacking in color, being, however, not altogether pale but rather sallow, and her glance was always intense and made with contracted brows.

Prokopios, Secret History (Anekdota) x.11–2 |

Theodora’s patronage

An important duty for a Byzantine empress was undertaking charitable causes. Here you see Prokopios describe the same act of Theodora’s patronage of a women’s monastery in two very different ways.

| And these Sovereigns have endowed this convent with an ample income of money, and have added many buildings most remarkable for their beauty and costliness, to serve as a consolation for the women, so that they never should be compelled to depart from the practice of virtue in any manner whatsoever.

Prokopios, Buildings I.ix.10 |

But Theodora also concerned herself to devise punishments against the body. Harlots, for instance, to the number of more than five hundred who plied their trade in the midst of the marketplace at the rate of three obols—just enough to live on—she gathered together, and sending them over to the opposite mainland she confined them to the Convent of Repentance, as it is called, trying there to compel them to adopt a new manner of life. And some of them threw themselves from a height at night and thus escaped the unwelcome transformation.

Prokopios, Secret History (Anekdota) xvii.5–6 |

Theodora’s public Image

In addition to being described as both beautiful and charitable, it was conventional in ancient and Byzantine rhetoric to portray a good empress as modest and poised in her demeanor. Consider these final two representations of Theodora: on the left, Prokopios’s account of Theodora before she became empress, and on the right, the artistic representation of Theodora as empress in San Vitale.

| And often even in the theatre, before the eyes of the whole people, she stripped off her clothing and moved about naked through their midst, having only a girdle about her private parts and her groins, not, however, that she was ashamed to display these too to the populace, but because no person is permitted to enter there entirely naked, but must have at least a girdle about the groins.

Prokopios, Secret History (Anekdota) ix.20 |

Theodora mosaic, 540s, San Vitale, Ravenna (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) |

Rhetorical conventions

Prokopios’s background and the rhetorical conventions of his time help illuminate these apparent contradictions in the primary sources above. Prokopios came to the Byzantine capital of Constantinople (modern Istanbul) from Caesarea in Palestine (modern Israel). He was well educated and may have belonged to a family of the old Roman aristocracy.

In Theodora’s time, writers like Prokopios trained in classical rhetoric—the Greco-Roman tradition of persuasion through the art of public speaking—that followed highly structured formulas. Their training from an early age focused on the ability to offer a positive and negative version of something equally well. Rhetoric textbooks taught writers how to spin facts to fit the larger purpose of a text.

Prokopios deploys established rhetorical formulas to praise Justinian and Theodora in Wars and Buildings while also criticizing the imperial couple in his Secret History. As modern readers, the apparent contradictions in these works might puzzle us as we seek to separate historical fact from fiction. But educated Byzantine readers of Prokopios’s time would have easily recognized the positive and negative accounts of the imperial couple as two different rhetorical genres known as encomium and invective, in effect, two different modes of speaking about the same subject.

The gendered politics of slander

Additionally, in the Roman world to which the Byzantine Empire was heir, it was a common political strategy to slander a wife or daughter in order to damage her husband or father. From the time of Rome’s first emperor, Augustus, detractors accused female members of the imperial family of engaging in prostitution as a way to try to diminish the emperor. If he can’t even control his own family—or so the rhetoric goes—how can he possibly rule the empire?

Modern receptions of the Secret History

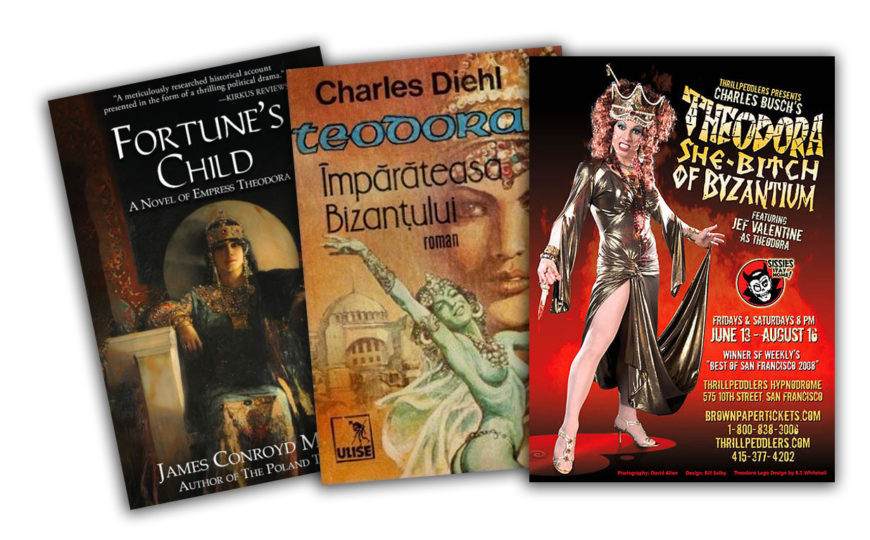

The Secret History, which includes many negative descriptions of Theodora, is also filled with accusations against her husband, the emperor Justinian. For example, the Secret History describes Justinian as a lord of the demons who allegedly wandered the imperial palace removing his head and carrying it in his arms. But while many modern readers have dismissed such fantastical descriptions of Justinian as a demon, they have often been willing to accept lurid descriptions of Theodora from the same text as truth. Modern fascination with these passages has also inspired popular depictions of Theodora in books, theater, and film.

Byzantine primary sources

The differing depictions of Theodora in the writings of Prokopios and the mosaics at San Vitale challenge us to consider how we approach primary sources from other periods and cultures. They remind us to be mindful of cultural conventions such as rhetoric before we accept their images and texts as literal, historical facts.

Additional resources

Smarthistory’s free Guide to Byzantine Art e-book

Anne McClanan, Representations of Early Byzantine Empresses: Image and Empire (New York; Palgrave, 2002)

Carolyn L. Connor, Women of Byzantium (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004)

Roland Betancourt, Byzantine Intersectionality: Sexuality, Gender, and Race in the Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020)