Robert de Luzarches, Thomas de Cormont, and Renaud de Cormont, Amiens Cathedral, Amiens, France, begun 1220; speakers are Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Visiting Amiens Cathedral

With its two soaring towers and three large portals filled with sculpture, Amiens Cathedral crowns the northern French city of Amiens. The cathedral is still one of the tallest structures in the city, its spire climbing nearly 400 feet into the air. You can see the skeletal stone structure on the exterior of the church, where flying buttresses support the upper walls like spider legs or a ribcage. The lace-like façade is made up of slender colonnettes and screen-like openings, heightening the contrast of light and shadow. Deeply set portals topped with tall gables pull the viewer in, an invitation to approach the building and cross the threshold.

Flying buttresses highlighted in red, Amiens Cathedral, begun 1220 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The Portal Sculpture

Through a series of intertwined images, each portal tells a story important to the Christian Church and the local Christian community through its stately sculpture. Within these portals, there is a whole sculpted universe to discover, with a multitude of figures, creatures, and narrative scenes, large and small. Some art historians have called this façade a sermon wrought in stone. If you visit the right portal, you will see images from the life of the Virgin Mary; in the left portal, you’ll find the story of Saint Firmin, the first bishop of Amiens, and images of local saints. Let’s take a closer look at the central portal.

The Beau Dieu, or beautiful God

The central portal announces its importance through its emphasized height and width. This is where you will find the trumeau figure of Christ—the Beau Dieu, or beautiful God—surrounded by the twelve apostles. You’ll notice that the figures on the portal at Amiens are sculpted with a high degree of realism, and that their heavy drapery hangs in languid folds on the figures’ bodies.

The Beau Dieu looks out onto visitors to the cathedral with an expression of peace, holding one hand in a gesture of blessing and a book in the other, signifying the importance of the biblical text. Originally, this figure and the rest of the portal sculpture would have been painted in dazzling colors, enhancing their lifelike qualities. Some of this polychromy remains along the hem of the Beau Dieu’s garment and in the outward gaze of the eyes.

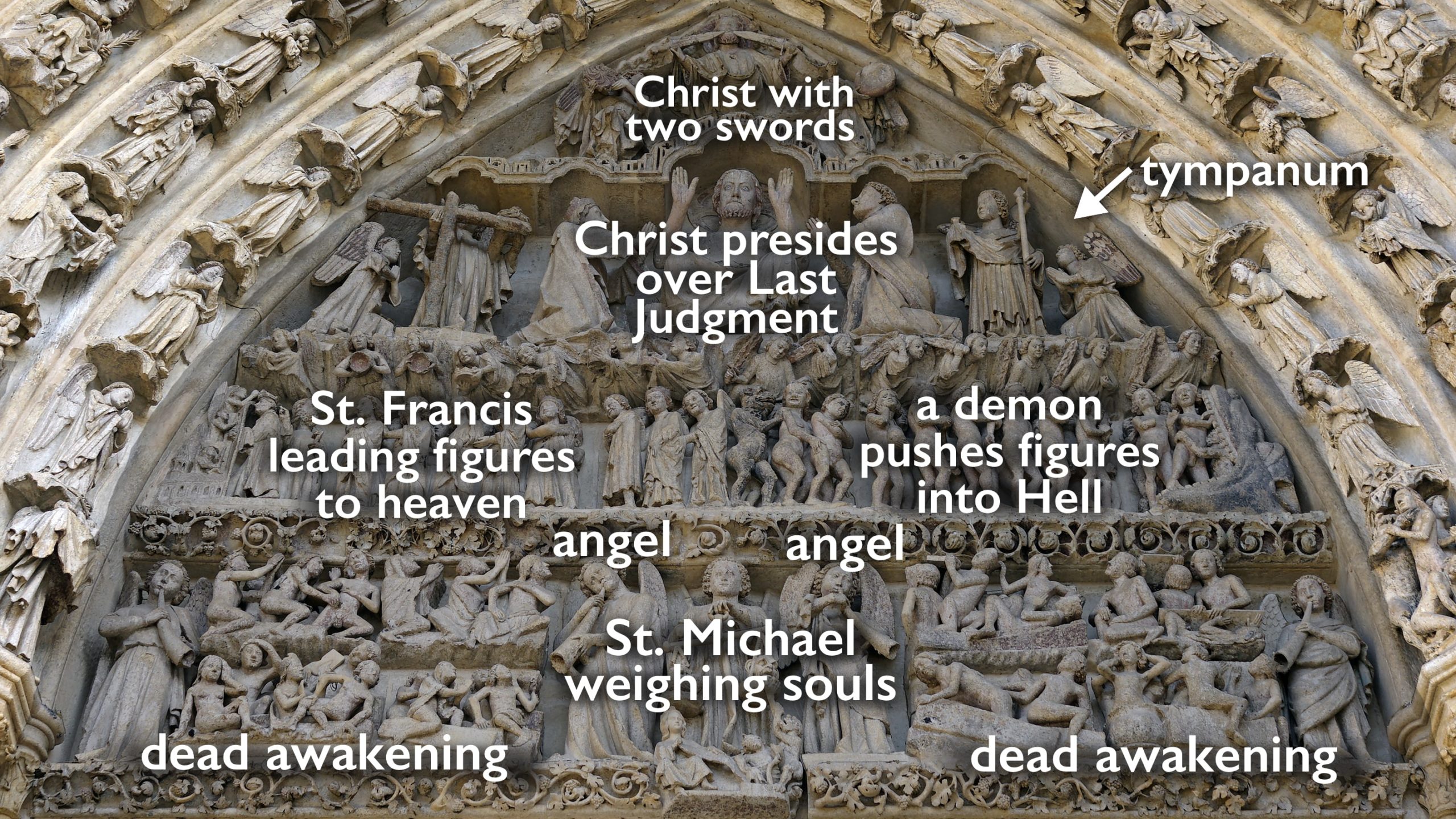

Tympanum

Above the trumeau, the tympanum depicts two more images of Christ. One version of Christ appears seated between kneeling figures of the Virgin Mary and St. John. He presides over the Last Judgment, a biblical event described in the last book of the New Testament, the Book of Revelation, in which the dead are awakened and sorted into Heaven and Hell.

On the lowest register of the tympanum, we see figures awakening from their tombs while St. Michael, flanked by trumpeting angels, weighs the souls of the dead. Above this register on the left, St. Francis leads a line of figures clothed in long robes into Heaven, where they are welcomed by St. Peter. On the right side of this register, a demon pushes a line of terrified, naked figures into the jaws of Hell. At the very top of the tympanum, a third image of Christ flies above the whole scene with two swords coming out of his mouth, a representation of the Christ of the Apocalypse, described in the Book of Revelation:

Coming out of his mouth is a sharp sword with which to strike down the nations. “He will rule them with an iron scepter.” He treads the winepress of the fury of the wrath of God Almighty. On his robe and on his thigh he has this name written: king of kings and lord of lords.Revelation 2:15

Courage (virtue) and fear (vice), west façade, Amiens Cathedral (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Virtues and vices

In addition to the three depictions of Christ, another set of images carved in relief appear at eye level: the Vices and Virtues. These quatrefoils are presented in pairs: Courage and Cowardice, Patience and Anger, Chastity and Lust.

The Virtues are represented by seated female figures holding shields, while narrative scenes depict the Vices. In the example illustrated here, the vice of cowardice is represented on the bottom as a knight so frightened by a small rabbit that he jumps away and drops his sword. Above, is the virtue of courage represented by a seated figure holding a shield with the image of a lion.

These images suggest to the viewer that they, too, can choose to follow a life of virtue, rather than a life of vice. By following this prescription, he or she can work towards an afterlife in the kingdom of Heaven, like St. Francis, and avoid the jaws of Hell.

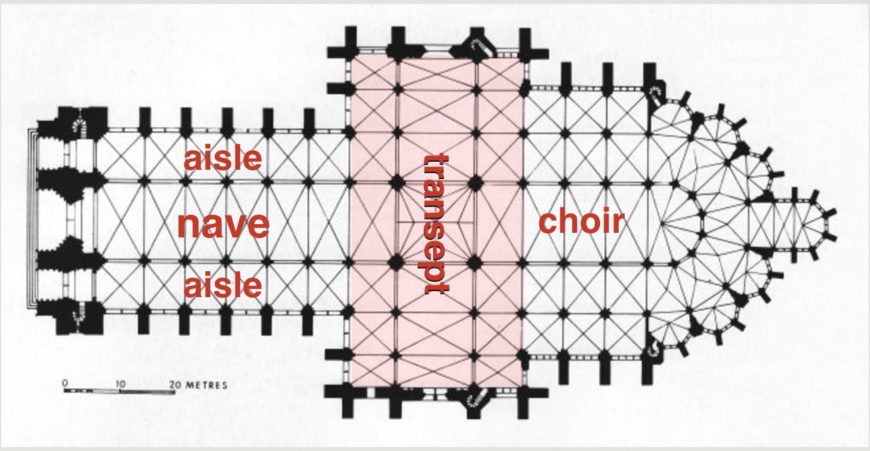

Interior plan

When you enter the cathedral (the entrance is on the west side), you might notice that the interior space is organized into three main aisles: a tall central aisle, called the nave, flanked by narrower aisles on either side. The church is laid out in a Latin cross plan, with a transept that intersects the nave and defines the choir.

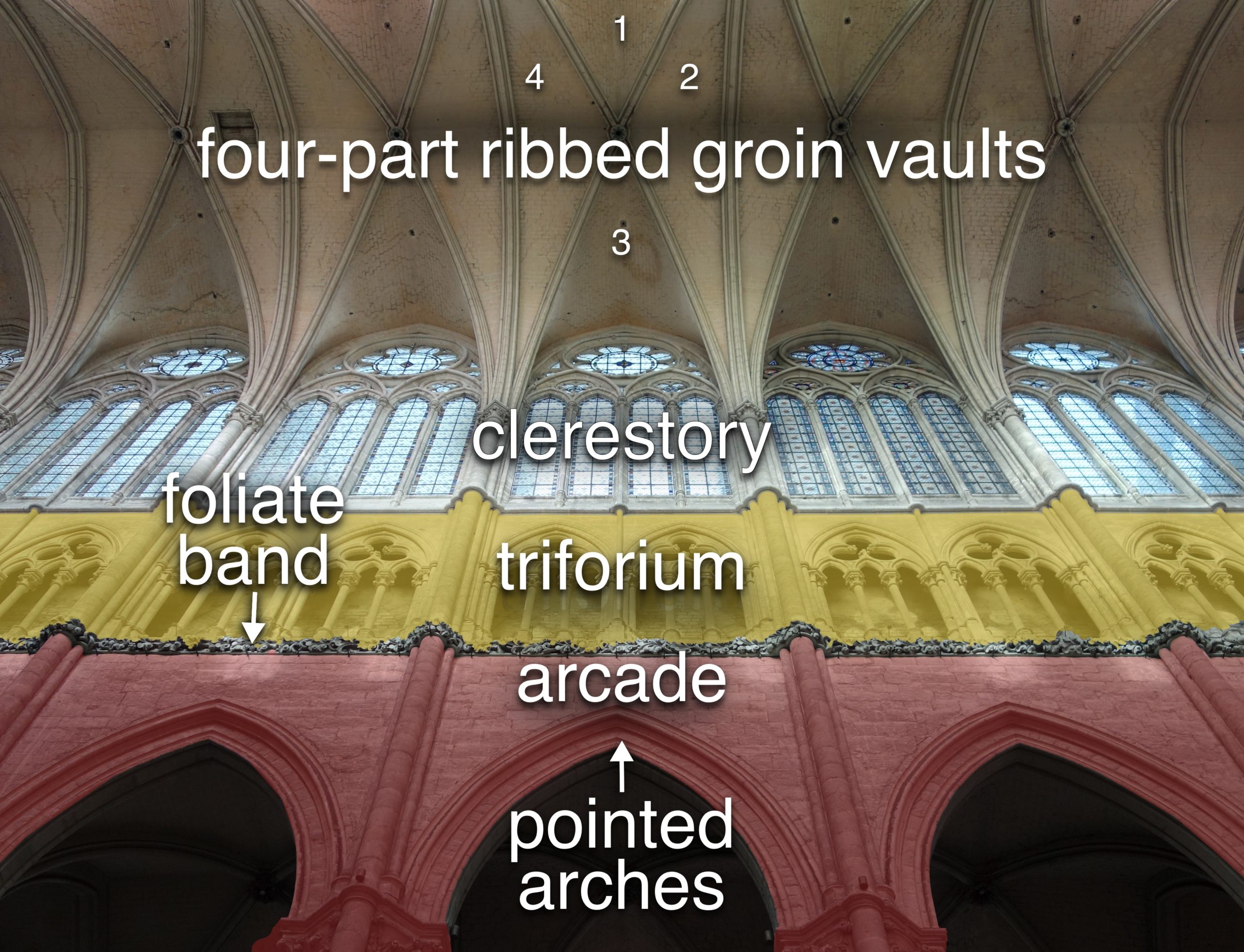

Interior elevation

If you look up, you’ll see that the building is made up of three levels: the arcade, the triforium, and the clerestory of tall windows. The large piers that support the main arcade are over six feet in diameter, supporting a series of pointed arches crowned with quadripartite ribbed groin vaults.

Just below the triforium, you might notice the sculpted foliate band that runs the entire length of the cathedral. This feature is unique to Amiens; no other Gothic cathedral from this period has comparable foliate carving as elaborate or monumental in scale. The foliate band is made up of hundreds of individually sculpted blocks that fit together to create a seamless line of foliage—though if you look closely, you’ll see subtle differences throughout the building. The foliate carving in the nave is robust, while the transepts have less emphasis on the fleshy leaves. In the choir, the pattern changes altogether. The three modes of foliate carving correspond roughly to the three phases of construction carried out by three separate architects.

Clerestory in the nave (flying buttresses visible through the windows), Amiens Cathedral, begun 1220 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Little remains of the original stained glass in the clerestory, which has been replaced with clear windows. Originally, light coming into the cathedral would have been filtered through the saturated jewel tones of colored glass. The medieval stained glass was removed before World War I as a precaution, but most of it was destroyed in a fire while in storage. The clear glass was installed later in the 20th century, incorporating fragments of medieval glass that survived. Some of the original panels can be seen in the choir triforium and rose windows.

Center of the Labyrinth, Amiens Cathedral, installed 1288. The original plaque is in the Musée de Picardie.

Labyrinth

Amiens Cathedral is not only one of the most important examples of Gothic architecture from the medieval period, it is an experiential work of art signed by its makers. At the center of a large labyrinth, we find a plaque that depicts four men: the bishop Evrard de Foulloy, under whose leadership the cathedral’s construction began, and three architects: Robert de Luzarches, Thomas de Cormont, and Thomas’s son, Renaud. It is unusual that we know the names of these medieval master masons, as few building records from this time survive. These architects directed the construction of the cathedral beginning in 1220 until the installation of the labyrinth pavement in 1288 (today’s pavement, a faithful replica of the original, was replaced in the 1880s). Even though work continued after 1288, much of what we see today is the creation of these architects and their teams of sculptors and stonecutters.

Glass behind the triforium in the choir, Amiens Cathedral, begun 1220 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Changes to the building’s design

You can notice changes in the building’s design as you compare work in the nave and transepts with the architecture in the choir. The last architect, Renaud de Cormont, made some departures from his father’s design, including installing stained glass behind the triforium instead of opting for a solid wall, changing the decorative sculpture in the capitals, and altering the design of the foliate band.

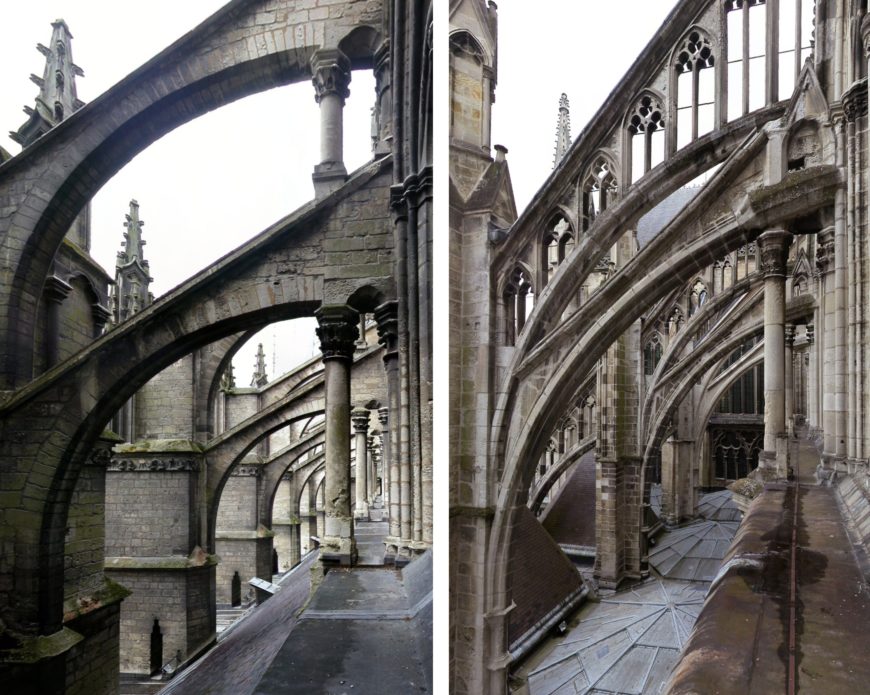

Unfortunately, some of these changes also led to structural instability in this part of the building. Just before 1500, one of the vaults suffered a partial collapse. The building had to be reinforced by an iron chain (still hidden inside the triforium today), and additional flying buttresses on the exterior.

On the exterior of this part of the building, we also see a difference in the flying buttresses: whereas the flying buttresses in the nave are solid, Renaud chose to use lace-like patterns in the openwork flying buttresses in the choir.

Why did Renaud do this? Art historians don’t have a definitive answer, but it is possible that the architect was responding to trends in Gothic design opting for more light, thinner supports, and more decorative qualities. Whatever the intention, the aesthetic effect is one of extraordinary delicacy.

In the choir, the architecture appears to float, as if the vaults were suspended above with little to support them. The added stained glass in the triforium would have filled this important part of the building—where the canons performed the mass in front of the high altar—with an ethereal light of dazzling color.

Through its architecture, sculpture, and history, Amiens Cathedral provides a window into the practice and culture of religious belief of the Middle Ages, as well as the ingenuity of medieval architects, masons, and artisans. This building stands as an irreplaceable example of the many dynamic forces at work in Gothic architecture.

Additional resources:

Amiens Cathedral (official website)

Life of a Cathedral: Notre-Dame of Amiens

Virtual Tour of Amiens Cathedral

Amiens Cathedral Construction Sequence

Jean-Luc Bouilleret, Aurélien André, and Xavier Boniface, eds. Amiens: la grâce d’une cathédrale (Strasbourg: La Nuée bleue, 2012)

Stephen Murray, A Gothic Sermon: Making a Contract with the Mother of God, Saint Mary of Amiens (Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, 2004)

Stephen Murray, Notre-Dame of Amiens: Life of the Gothic Cathedral, Columbia University Press, 2020

Stephen Murray, Notre-Dame, Cathedral of Amiens : The Power of Change in Gothic (New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 1996)

Dany Sandron, Amiens, La Cathédrale (Paris: Zodiaque, 2004)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”Amiens17,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:04] We’re standing in the square outside of the beautiful 13th-century cathedral of Amiens. This is a Gothic masterpiece, both in architecture and sculpture.

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:15] This is such a great example of the Gothic because the front of the building is not so much a stone wall but a complex surface that’s almost like lace in the way that it’s opened up.

Dr. Harris: [0:24] Starting at the bottom, we have these three large doorways. That mirrors what we would find inside a church, a large central nave and then smaller aisles on either side. To call these doors is such an oversimplification. These are decorated with dozens of figures and almost act like funnels that draw us into the church.

Dr. Zucker: [0:48] Yes. There is a sense of movement in, but at the same time there’s a sense of amplification outward. It’s almost as if the messages of the figures that are carved within these portals, that their voices are amplified by the multiple arches that radiate outward.

Dr. Harris: [1:01] Above the doorway, we see pointed arches decorated with quatrefoils. Then, typically for many Gothic churches, we see a row of figures, standing in niches, and this is called the kings gallery.

Dr. Zucker: [1:14] Then on either side, two towers, which are actually later additions.

Dr. Harris: [1:18] In between that, a rose window.

Dr. Zucker: [1:20] The kings gallery functions as a Tree of Jesse, that is, the lineage of Old Testament kings that Christians believe were the ancestors of Christ.

Dr. Harris: [1:28] One way we could understand this is to think about this left portal as telling us the stories of a local saint, who would’ve been especially venerated by the people of Amiens as their first bishop. On the right, we have Mary, the intercessor between mankind and God. Then in the center we see Christ presented to us in three ways.

Dr. Zucker: [1:48] Let’s take a close look at the portal that’s devoted to the Virgin Mary.

Dr. Harris: [1:52] Here we see Mary holding the Christ Child on the trumeau.

Dr. Zucker: [1:56] She’s stepping on a creature that has a human head, but attached to a lizard-like body, which represents evil that she’s stomping out. The Virgin is so elegantly represented. She holds the Christ Child, her palm is forward as if she’s presenting him to us. You can still make out the blue paint that would’ve originally covered her dress.

Dr. Harris: [2:15] So much of the paint is still visible. You see reds, and blues, and golds.

Dr. Zucker: [2:19] She’s crowned because this is a representation of Mary as the Queen of Heaven. Above her, we see an architectural structure that is a kind of tabernacle. Within it is a representation of the Ark of the Covenant, and that’s the ark that would’ve held the 10 Commandments.

Dr. Harris: [2:33] On either side of that, we see three patriarchs. Above that, in the tympanum, two scenes from the life of the Virgin; the Dormition, or the death of the Virgin.

Dr. Zucker: [2:42] That’s on the left.

Dr. Harris: [2:44] On the right, the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. Mary was understood to have been assumed bodily into heaven, and we see angels lifting her up.

Dr. Zucker: [2:53] Both of those sculptures, although they tell different stories, seem so similar at first. I love the slight distinctions that help us tell one from the other. On the right, Mary is lifted ever so slightly.

Dr. Harris: [3:06] If we move up to the very top of the tympanum, we see a scene that is quite common in Gothic sculpture. That’s the Coronation of the Virgin Mary. Angels are placing a crown on the head of the Virgin Mary as Queen of Heaven, and she’s surrounded by angels.

Dr. Zucker: [3:22] Let’s spend a moment looking at some of the jamb figures on either side of the doorway. We see the Annunciation. On the left is the Archangel Gabriel announcing to the Virgin Mary that she will bear Christ.

Dr. Harris: [3:33] Then, next to that, we see the Visitation. This is Mary being visited by her cousin, Elizabeth, who’s pregnant with Saint John the Baptist. Mary is pregnant with the Christ Child.

Dr. Zucker: [3:43] I love the sense of naturalism in these figures, the way in which they’re interacting. This is quite different from the earlier jamb figures that we see at Chartres, where the figures are very separate, very columnar.

Dr. Harris: [3:53] Here, the drapery falls quite naturally in folds that appear three-dimensional. There’s not a lot of interest here in showing the body underneath the drapery. There is a plainness and simplicity of the figures in their drapery and in their faces that has been noted by art historians.

Dr. Zucker: [4:11] One aside — below the feet of the jamb figures, there are these architectural canopies, and below that, wonderfully complex figures. In some cases, they seem to relate directly to the figures above them. For instance, just below the Virgin Mary, you see Eve, who’s being offered the apple by the devil in the guise of a serpent.

Dr. Harris: [4:30] Mary is understood in Christian theology as the second Eve, who, with Christ, sets right the Original Sin created by Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden.

Dr. Zucker: [4:39] We’ve walked over to the central portal. Let’s start in the very center with the trumeau.

Dr. Harris: [4:43] This figure is known as the Beau Dieu, the Beautiful God, and he is beautiful. He looks peaceful. He’s got his right hand raised in a gesture of blessing. In his left hand he holds a book.

Dr. Zucker: [4:55] Look how his drapery points upward towards the Bible, drawing our eye to the word of God.

Dr. Harris: [5:00] We get a sense of being blessed as we enter the church. We also note that Christ is standing on two creatures: one that looks like a lion, another that looks like a dragon or a serpent. Again, that idea of good overcoming evil.

Dr. Zucker: [5:15] What I find fascinating is that this is the lowest of three representations of Christ. We also find Christ as judge in the tympanum, and above that, an apocalyptic Christ. Let’s take a look at the tympanum more closely.

Dr. Harris: [5:27] The tympanum is, in a way, a warning.

Dr. Zucker: [5:29] Christ sits as judge, in this case, on a low stool. His palms are up, and if you look very closely, you can just make out drops of blood coming from his wounds from the cross.

Dr. Harris: [5:39] All of these figures who look very real to us today would have appeared so much more lifelike when they were painted.

Dr. Zucker: [5:46] Christ’s pupils are still painted. His eyes look out at us with wonderful intensity.

Dr. Harris: [5:50] This is the Last Judgment. On the left, we see Mary. On the right, Saint John. On either side of them, angels holding the instruments of the Passion.

Dr. Zucker: [5:59] Then kneeling angels at the far corner. In the register just below Christ, we see the blessed and the damned. The damned are on the right. They’re naked and they’re being forced by devils into the mouth of hell itself.

Dr. Harris: [6:11] Angels above them brandish fiery swords, pushing them into that mouth of hell.

Dr. Zucker: [6:16] If you look closely, the figures that are closest to the mouth of hell, who seem to be trying to turn away, are being pulled in by a devil’s arm.

Dr. Harris: [6:24] Of course, escape is impossible. On the left, we see the blessed, who are being escorted in an orderly way into heaven, where they’re being crowned. Angels gently guide them by placing a hand on their back. The angels above them place crowns on their heads.

Dr. Zucker: [6:41] At the bottom of the tympanum, we see four angels blowing trumpets. They are waking the dead. We can see souls rising out of their tombs, lifting the heavy stone slabs from their coffins. Some have their hands in prayer and some seem simply bewildered. Each of these souls will be judged.

Dr. Harris: [7:00] In the center, we see Saint Michael, who’s weighing souls. He’s got a scale. On the left side, we see a lamb, the Lamb of God, which is understood as Christ. On the right, a demon. It looks as though the weight of the scale is toward the side of the lamb, toward the side of the blessed. Souls are being weighed to decide their fate, whether they go to heaven or they go to hell.

Dr. Zucker: [7:23] If you look very closely, you can see that there’s a demon below the scales who’s lifting his arm and is trying to tip the balance. He’s trying to cheat. At the very top, we see the third representation of Christ, but this is the apocalyptic Christ that comes directly from the book of Revelation.

Dr. Harris: [7:38] In that book, it says, “In his right hand, he held seven stars, and coming out of his mouth was a sharp, double-edged sword. His face was like the sun shining in all of its brilliance.”

Dr. Zucker: [7:42] We see two angels. The angel on the left holds the sun, and the angel on the right, the moon. The Last Judgment is this division between the blessed and the damned. Above the central portal, it’s a reminder to everybody entering and leaving the church that they can live their life in a way that is in accordance with God or not. We see that also in the lower registers of the portal.

Dr. Harris: [8:10] The tympanum is addressing what will happen in our afterlife based on the choices we make while we’re alive. We’re reminded of those choices in the quatrefoils just below the jamb sculptures, where we see, in some cases, representations of virtues and vices.

[8:26] The one I love the most is the pair of courage and cowardice. Courage shows us a knight holding a shield and a sword.

Dr. Zucker: [8:34] On the shield, we see a representation of a powerful creature. I think that might be a bear.

Dr. Harris: [8:39] That sword has been dropped quickly.

Dr. Zucker: [8:41] We see this figure of cowardice turning back, startled by two little animals…

[8:47] [laughter]

Dr. Zucker: [8:47] …a rabbit and a bird, and he seems to be running away. It is a wonderful contrast. Even though this is carved in a lighthearted way, below the surface is a serious message. Those that come into the church are being reminded that they have choices that will have powerful consequences in the afterlife.

Dr. Harris: [9:04] And that the Virgin Mary is available to intercede on our behalf. We’re reminded of that in the right portal. The first Bishop of Amiens is also there for us, as we’re reminded in the left-hand portal. We have these tools available to us to aid in our salvation as we enter the miraculous space of Amiens Cathedral.

Dr. Zucker: [9:27] It’s quieter, but surprisingly bright.

Dr. Harris: [9:30] The stained-glass windows that would have been here in the 13th century don’t survive, and so we’re not quite seeing the interior the way it would have been seen back then.

[9:39] Standing in the nave, the main wide central space of the church, we notice that there’s one aisle on either side. When we look down the nave, we see the holiest part of the church, the east end, where the altar is.

Dr. Zucker: [9:53] If we follow the great piers that do much of the work of the building, supporting the vaulting above, our eye rises up to the triforium, and then to these massive walls of glass, what art historians call a clerestory.

Dr. Harris: [10:08] Amiens is a High Gothic church, and this vocabulary of Gothic architecture is being utilized here to its fullest. That clerestory is so important. The idea of letting light into the church, of opening up the walls, and that spiritual quality of light, so important to the Gothic architects.

Dr. Zucker: [10:28] The clerestories themselves are much more elaborate than have been seen in earlier Gothic cathedrals. They’re made up of a pair of arches, each with a pair of lancet windows. Then above, there are smaller oculi — in this case, round, four-lobed windows — and above that, a larger round rose window.

Dr. Harris: [10:45] Even the spaces between the double arches and that large rose are opened up to the light.

Dr. Zucker: [10:51] Now, all of this seems absolutely miraculous. There’s this massive stone vault above. How is it possible that the glass holds that up? Some of the weight is held up by the piers, but if you look closely through the now clear glass, you can see the shadows of one of the great innovations of Gothic architecture, the flying buttress.

[11:12] This draws the weight of the vaulting outside, so that the interior walls and the interior piers can be much more slender than had been possible in earlier forms of architecture.

Dr. Harris: [11:22] Those buttresses are helping from outside to support the building.

Dr. Zucker: [11:26] If you look very closely, you’ll know that they’re pairs of flying buttresses, and that’s because the lower of the two was added later when the great weight of the cathedral was creating a buckling. This helped stabilize the structure.

Dr. Harris: [11:39] This is before modern engineering. This is a little bit of trial and error involved by the master builders who worked on this church, by the way, whose names were mentioned in the labyrinth that once occupied the crossing of the church. There was a recognition of the importance of these master builders.

Dr. Zucker: [11:58] And their role in creating an architecture that was a reflection of heaven in the earthly sphere.

Dr. Harris: [12:03] It’s important to notice, too, that the Gothic architects are making use of the pointed arch, which allowed them much greater flexibility than the round arches used by Romanesque architects.

Dr. Zucker: [12:14] The thrust of a pointed arch pushes down more directly. A rounded arch pushes out more, and this allows the architects to build higher.

Dr. Harris: [12:23] We also notice in Gothic architecture that they’re making use of the ribbed groin vault, yet another technical achievement that allowed the architects to build so high and to build such vast spaces. We have this space that is incredibly high and open, with very thin columns that support this roof that doesn’t appear to weigh anything at all.

Dr. Zucker: [12:46] The entire space feels miraculous, even today.

Dr. Harris: [12:50] Romanesque churches, in the period before the Gothic, you walked in and you were met with vast expanses of walls that were covered with paintings, with murals that told biblical stories. Here, those walls are opened up. It’s the light that is communicating the divine.

Dr. Zucker: [13:08] A great example of that can be seen in one of the later parts of the cathedral. Here, the solid wall of the triforium is opened up and becomes an additional set of windows, making the church feel even more diaphanous.

Dr. Harris: [13:19] As we look at the piers, which are doing much of the work of carrying the weight of the vault, the way that they appear to be almost like bundled groups of smaller columns again give[s] us that sense of lightness, of delicacy, of removing that sense of weight.

Dr. Zucker: [13:36] Of masking their massiveness.

Dr. Harris: [13:38] One of my favorite parts of the church is the lovely sculpting that we see on the stringcourse just above the nave arcade that helps to draw our eye down toward the east end.

[13:49] This is the time when the University of Paris is established. There’s a going back to ancient philosophers, especially Aristotle, and a desire to unify the logical thinking found in Aristotle with Christian theological ideas. We know that geometry was very important to Gothic architecture.

Dr. Zucker: [14:09] The idea was that the church’s proportions ought to correspond to the ideal of heaven. One of the ways that architects would do that is to think about dimensions that are spoken of in the Bible. One of the most famous is Noah’s Ark, which was known to be 50 cubits.

[14:23] Architectural historians have surmised that the central square of the church, right in the middle of the crossing, is the basis for the proportions of the church as a whole. This theory suggests that that inner square is 50 feet on each side, but that square is then extended 30 feet on each side in accordance with the Golden Section, making a great square which is 110 feet on each side.

Dr. Harris: [14:46] This unit forms a module that gets repeated through parts of the church.

Dr. Zucker: [14:51] For example, in order to get the width of the transept, of the great crossing that makes the outline of the church into a cruciform, into the shape of a cross, one needs to simply take 50 percent of the great square and add that again to either side. Similarly, if you take the diagonal of the great square, that is the length of the nave.

[15:10] Again, if you take the diagonal of the great square and you turn it 90 degrees upward, you have the height of the nave.

Dr. Harris: [15:16] What all of this suggests is a desire to unify the church, to use a system of measurement that is somewhat consistent.

Dr. Zucker: [15:23] But also based on a kind of ideal that comes from the Bible. Because this entire enterprise, this entire cathedral, is meant to represent heaven on earth.

Dr. Harris: [15:33] To lead the human mind toward the divine, and therefore toward our salvation.

[15:38] [music]