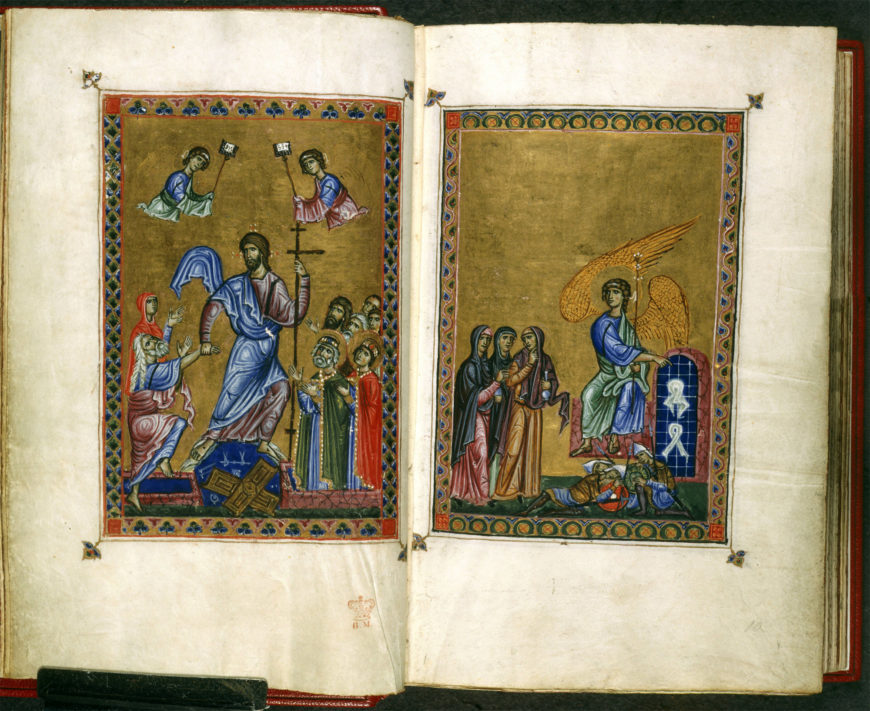

The Harrowing of Hell (left) and the three Marys at the tomb (right), the Melisende Psalter (Egerton 1139, 9v and 10r), 1131–1143 (© The British Library)

The Melisende Psalter is a manuscript from the 12th century, which contains the book of Psalms, as well as prayers and a calendar. It is a product of the crusading movement, in which western European Christians sought to capture Jerusalem and the surrounding area from Muslims rulers and maintain control of the region by establishing crusader states.

The crusader states, 1135 (Amitchell125, CC BY-SA 4.0)

It shows the ways that the artistic traditions of western Europe and the Byzantine Empire—an eastern Christian empire whose nearby capital was Constantinople (modern Istanbul) and where Greek was the predominant language—could converge as a result of the crusades. The Melisende Psalter also offers us insight into the life of a remarkable medieval woman: queen Melisende of Jerusalem.

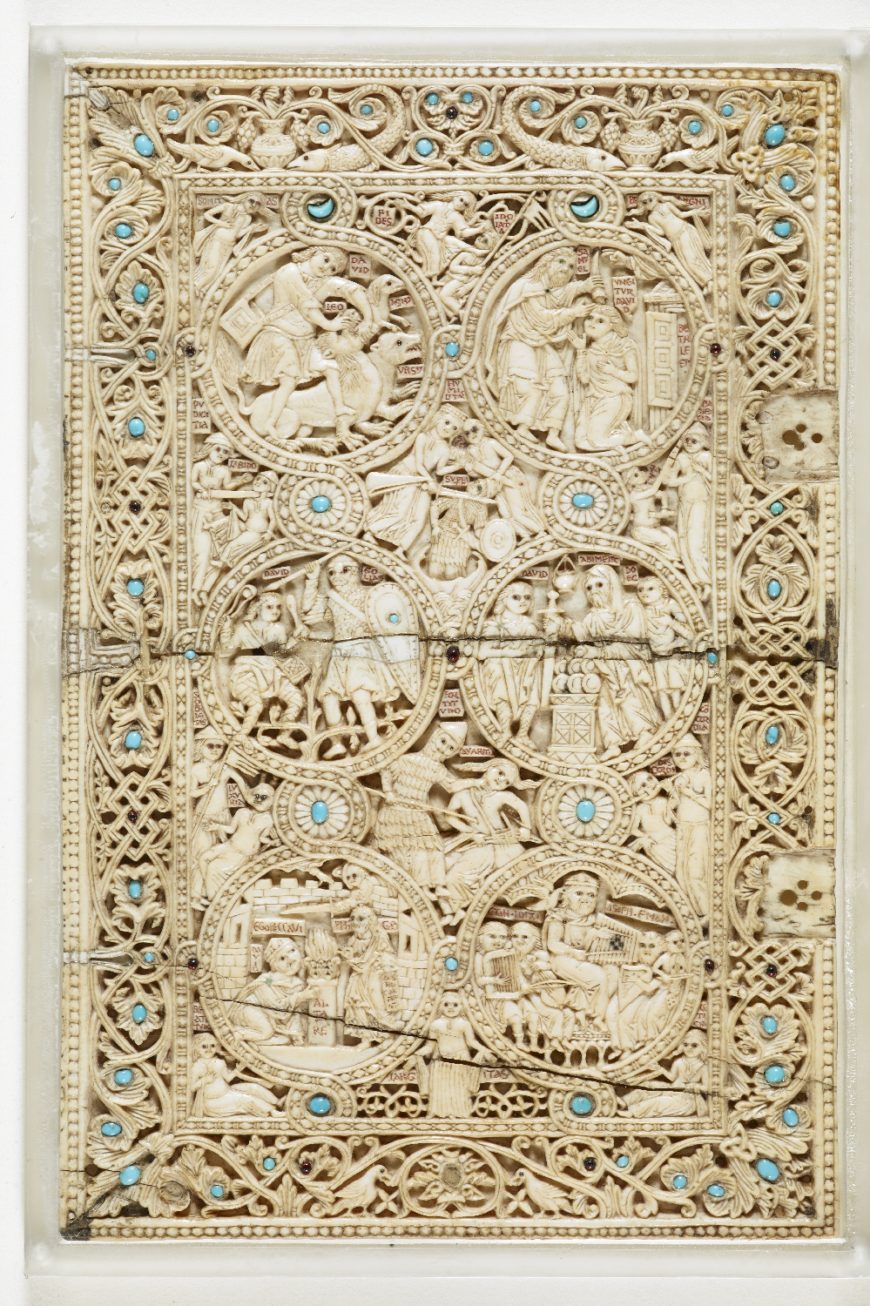

Upper cover of the Melisende Psalter, 1131–1143, ivory (© The British Library)

Ivory book covers

The Melisende Psalter is so well-preserved that even its original ivory covers survive—a rare occurrence with medieval books. These ivory covers exemplify the way crusader art often interwove cultural elements imported by the western European crusaders with more local traditions, such as those found in the Byzantine Empire. The top cover shows, in six circles, scenes from of life of King David—a figure from the Hebrew Bible who was widely regarded as a role model by medieval rulers. In the roundel on the bottom right, David appears with a lyre as the author of the book of Psalms, the contents of this very book. View annotated image.

David with his harp (right), detail of upper cover of the Melisende Psalter, 1131–1143, ivory (© The British Library)

David composing the Psalms, Paris Psalter (Paris Grec 139, 1v), Byzantine, 940–960 (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

The ivory cover follows a long tradition of connecting current medieval rulers with the biblical king David, as we see in this Byzantine manuscript, the Paris Psalter, which shows David hard at work composing the Psalms, and which was likely produced for a Byzantine emperor.

The rich symbolism of the ivory cover of the Melisende Psalter doesn’t stop there, because in between those ivory medallions with King David, a battle for human will is waged by allegorical representations of virtues and vices. Such depictions of abstract concepts in the form of human figures were common in western medieval art. For example, on the lower left, beneath the medallion showing David fighting Goliath, sobriety (sobrietas) is shown holding a banner and conquering luxury (luxuria). View annotated image.

David fights Goliath (top), sobriety conquers luxury (lower left), detail of upper cover of the Melisende Psalter, 1131–1143, ivory (© The British Library)

Melisende Psalter illuminations

Despite this visual warning against luxury on the cover of the Melisende Psalter, the manuscript found inside is splendidly illuminated. The Melisende Psalter has 218 folia plus some loose leaves, and opens with images of key moments in the life of Christ, all in the style favored by the crusader courts that mimicked the icons of the Byzantine Empire.

Harrowing of Hell, the Melisende Psalter (Egerton 1139, 9v), 1131–1143 (© The British Library)

The Harrowing of Hell

The Harrowing of Hell, or Anastasis, scene employs imagery, or iconography, which has been directly borrowed from Byzantine art. A towering Christ strides dynamically through the center of the scene, his blue and purple clothes rippling with motion. In his left hand he holds the cross on which he was crucified, and with his right hand he raises the souls of the dead from their tombs.

The composition includes typical Byzantine details that illustrate Christ’s victory over death, such as the broken locks and doors of hell—used to imprison the souls of the dead—which Christ now tramples underfoot. These same details can be observed in contemporary works of Byzantine art, such as this eleventh-century mosaic at the monastery of Hosios Loukas.

Anastasis mosaic, Byzantine, 11th century, Hosios Loukas monastery, Boeotia, Greece (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the Melisende Psalter’s image of the Harrowing of Hell, the angels hovering above Christ hold standards bearing the letters “SSS,” an abbreviation for the angelic hymn, “holy, holy, holy,” which is taken from Isaiah 6:3, and which was also sung in both the Latin church services of western Europe and the Greek services of the Byzantine Empire. This “SSS” abbreviation stands for “sanctus, sanctus, sanctus,” the Latin (rather than Greek) version of this text, suggesting that what initially appears to be a Byzantine image was intended for western European rather than Byzantine viewers.

Detail of the Harrowing of Hell, the Melisende Psalter (Egerton 1139, 9v), 1131–1143 (© The British Library)

The artist’s signature

The artist who painted the twenty-four opening scenes for this manuscript even signed his name—Basilius—an unusual flourish in a time when most artists remained anonymous.

Deësis, the Melisende Psalter (Egerton 1139, 12v), 1131–1143 (© The British Library)

Like the Harrowing of Hell image, the artist’s inscription, Basilius me fecit (“Basil made me”), similarly seems to intermingle the medieval cultures of the Byzantine Empire and the Latin West: the artist’s name is Greek, possibly suggesting a connection with the Byzantine Empire, while the inscription is in Latin.

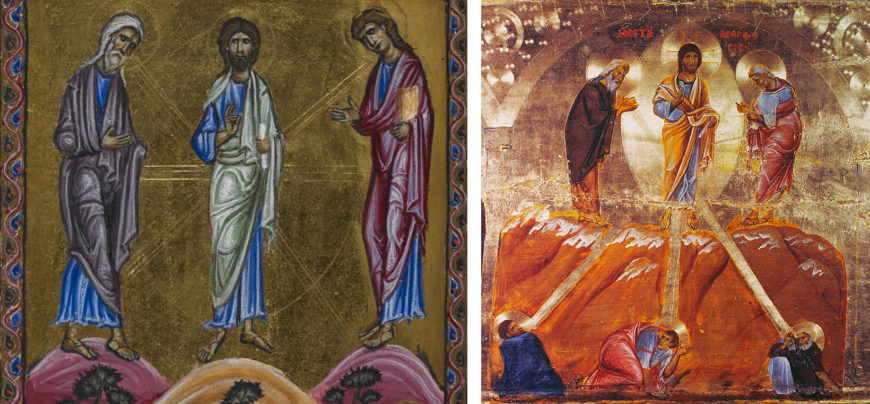

The Transfiguration, the Melisende Psalter (Egerton 1139, 4v), 1131-1143 (© The British Library)

The Transfiguration

The Transfiguration scene also shows that Basilius was aware of contemporary art trends. It closely resembles Byzantine renderings of this moment from the New Testament when Christ is transfigured by divine light before the events leading to his crucifixion: “And he was transfigured before them, and his face shone like the sun, and his clothes became dazzling white” (Matthew 17:2). The artist even deployed contemporary Byzantine aesthetic principles, emphasizing subtle modulations of light in the gold beams radiating from Christ, which can also be observed in Byzantine depictions of the Transfiguration, as on this templon beam at the Monastery of Saint Catherine at Sinai.

Left: Melisende Psalter; right: The Transfiguration, detail of a templon beam, Byzantine, c. 1200, Monastery of Saint Catherine, Sinai (photo: Princeton University)

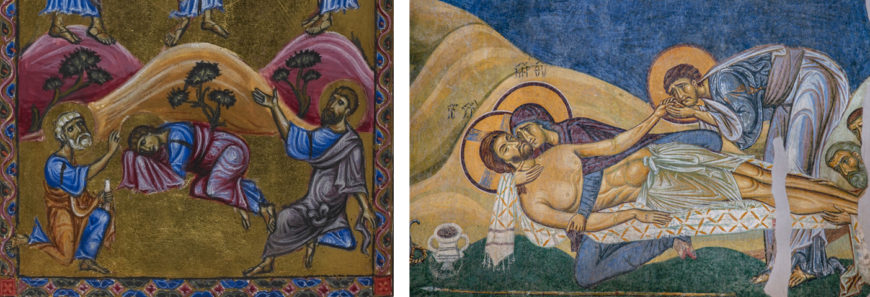

The apostles Peter, John, and James show their astonishment at Christ’s Transfiguration with an exaggerated emotionalism that can also be found in Byzantine art from this same period, for example in the twelfth-century fresco of the Lamentation at the church of Saint Panteleimon at Nerezi (North Macedonia).

Left: Melisende Psalter; right: Detail of the Lamentation at Saint Panteleimon, Nerezi (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

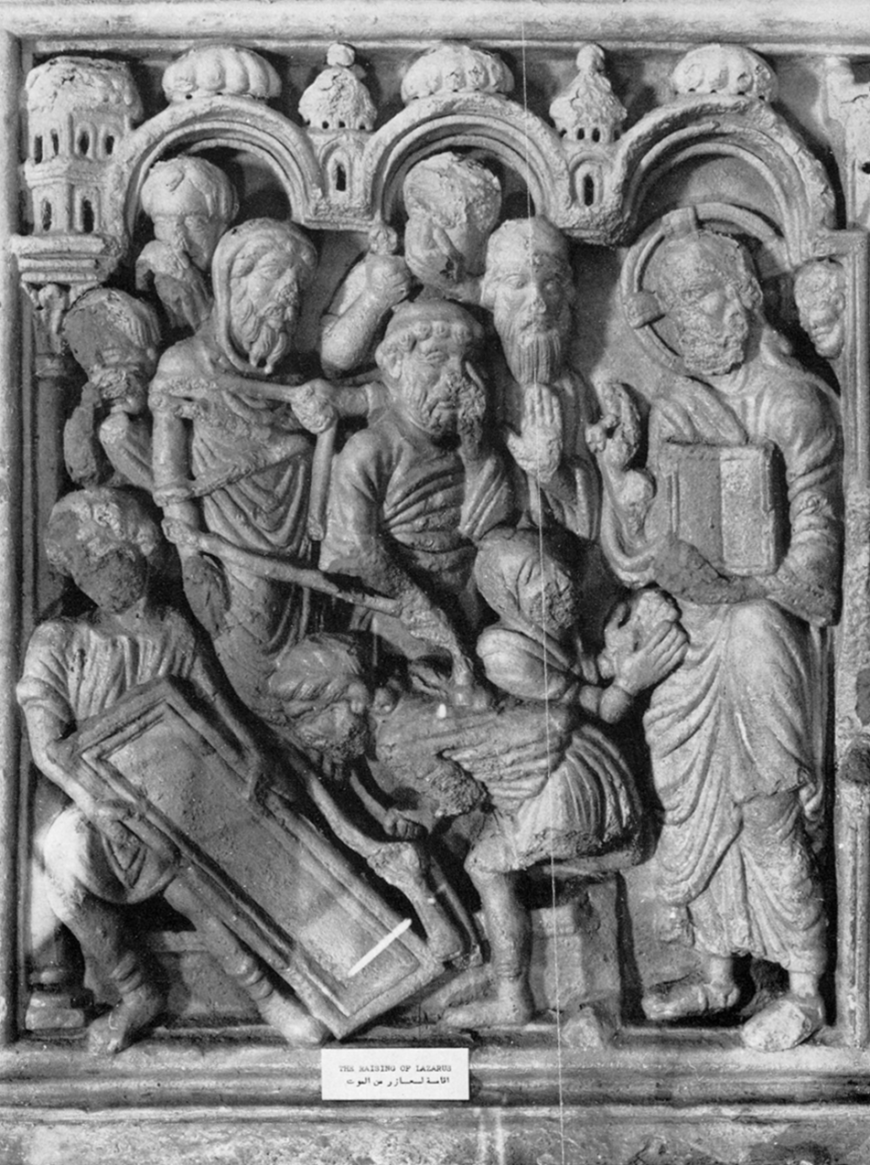

The Raising of Lazarus

On the other hand, this scene of the raising of Lazarus displays influence from western European as well as Byzantine art. While the gold background and stylized depictions echo the style of Byzantine art, Lazarus emerges from the arched opening of a building, rather than a rock-cut tomb, as typically appears in Byzantine representations of the scene.

The Raising of Lazarus, the Melisende Psalter (Egerton 1139, 5r), 1131–1143 (© The British Library)

This non-Byzantine-style depiction of Lazarus’s tomb can be compared to another image of the Raising of Lazarus from a carved lintel dated to c. 1149 at the church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem—a building that Melisende helped renovate and expand in the 1140s. In this carved version of the scene, Lazarus similarly emerges from beneath an arch with depictions of buildings above.

Christ (right) commands that Lazarus’s tomb be opened. Two men remove the tombstone (lower left) while others unwind Lazarus’s grave clothes above, The Raising of Lazarus, detail from a lintel of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, c. 1149

The patron of the Melisende Psalter

This and other evidence has led art historians to conclude the manuscript was made in the workshop of the church of the Holy Sepulchre in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem—an important center for book production under crusader rule—during the twelfth century. But who inspired this remarkable manuscript? We find a clue in the Latin used for the manuscript’s prayers that use feminine endings (such as peccatrix, “sinner”), narrowing the possibilities to the aristocratic women in the crusading movement.

The crusader states, 1135 (Amitchell125, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Queen Melisende is the most likely option. The daughter of the crusader king Baldwin II and the Armenian queen Morphia, because Melisende had no brothers she became the heir presumptive to the crusader throne and was included in official documents issued by her father, King Baldwin II. Her parents moreover are mentioned in the manuscript’s calendar on 21 August and 1 October, respectively, further suggesting a connection to her immediate family.

Coronation of Fulk and Melisende, c. 1275, northern France (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS fr. 779, fol. 123v)

As the heir to the Crusader throne, Melisende expected that when she married Fulk, Count of Anjou (France), she would rule as an equal partner following the death of her father in 1131. Instead, Fulk tried to exclude Melisende and rule alone, with disastrous results: Fulk failed to consolidate power and the Kingdom of Jerusalem was plunged into civil war.

Perhaps this gorgeous manuscript was intended as a gesture to appease the brilliant queen Melisende when, in 1135, Fulk accepted that he must share rule with his queen. Or perhaps the powerful queen Melisende commissioned it herself.

Additional resources

Smarthistory’s free Guide to Byzantine Art e-book

“The Melisende Psalter,” British Library

Sarah J Biggs, “Twelfth-Century Girl Power,” British Library

Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb, ed., Jerusalem, 1000-1400, Every People under Heaven (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2016), no, 121, pp. 244–246.

Hugo Buchthal and Francis Wormald, Miniature Painting in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1957)