Periods of Byzantine history

Early Byzantine (including Iconoclasm) c. 330 – 843

Middle Byzantine c. 843 – 1204

The Fourth Crusade & Latin Empire 1204 – 1261

Late Byzantine 1261 – 1453

Post-Byzantine after 1453

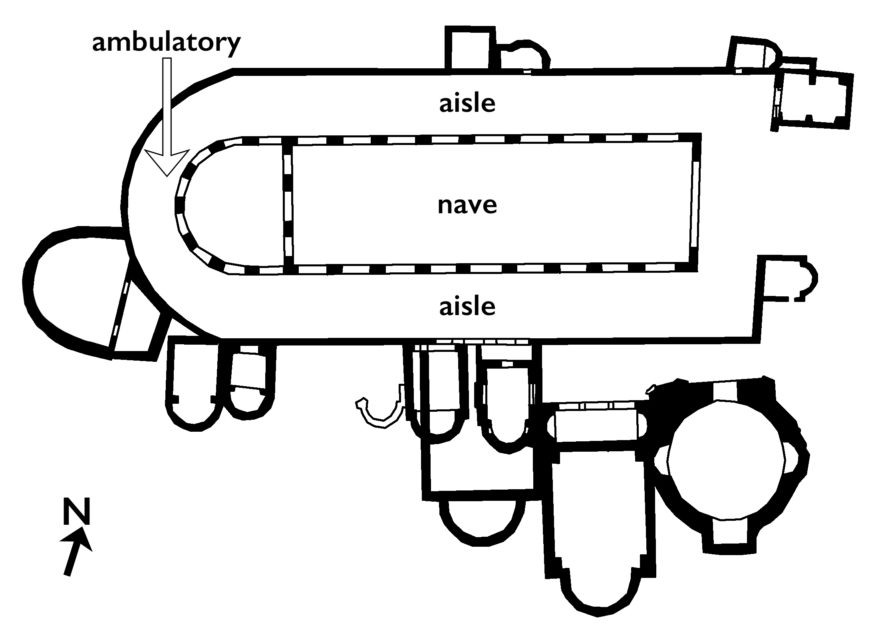

Dura Europos, house church floor plan, c. 230 (adapted from plan by Udimu, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Buildings for a minority religion

Officially Byzantine architecture begins with Constantine, but the seeds for its development were sown at least a century before the Edict of Milan granted toleration to Christianity in 313 C.E. Although limited physical evidence survives, a combination of archaeology and texts may help us to understand the formation of an architecture in service of the new religion.

The domus ecclesiae, or house-church, most often represented an adaptation of an existing Late Antique residence to include a meeting hall and perhaps a baptistery. Most examples are known from texts; while there are significant remains in Rome, where they were known as tituli, most early sites of Christian worship were subsequently rebuilt and enlarged to give them a suitably public character, thus destroying much of the physical evidence.

Synagogues and mithraia from the period are considerably better preserved. A notable exception is the Christian House at Dura-Europos in Syria, built c. 200 on a typical courtyard plan. Modified c. 230, two rooms were joined to form a longitudinal meeting hall; another was provided with a piscina (a basin for water) to function as a baptistery for Christian initiation.

Another house-church, considerably modified, was the house of St. Peter at Capharnaum, visited by early pilgrims.

Early Christian burials

Better evidence survives for burial customs, which were of prime concern in a religion that promised salvation after death. Unlike pagans, who practiced both cremation and inhumation (burial), Christians insisted upon inhumation because of the belief in the bodily resurrection of the dead at the end of days. In addition to areae (above-ground cemeteries) and catacombs (underground cemeteries), Christians required settings for commemorative banquets or refrigeria, a carry-over from pagan practices.

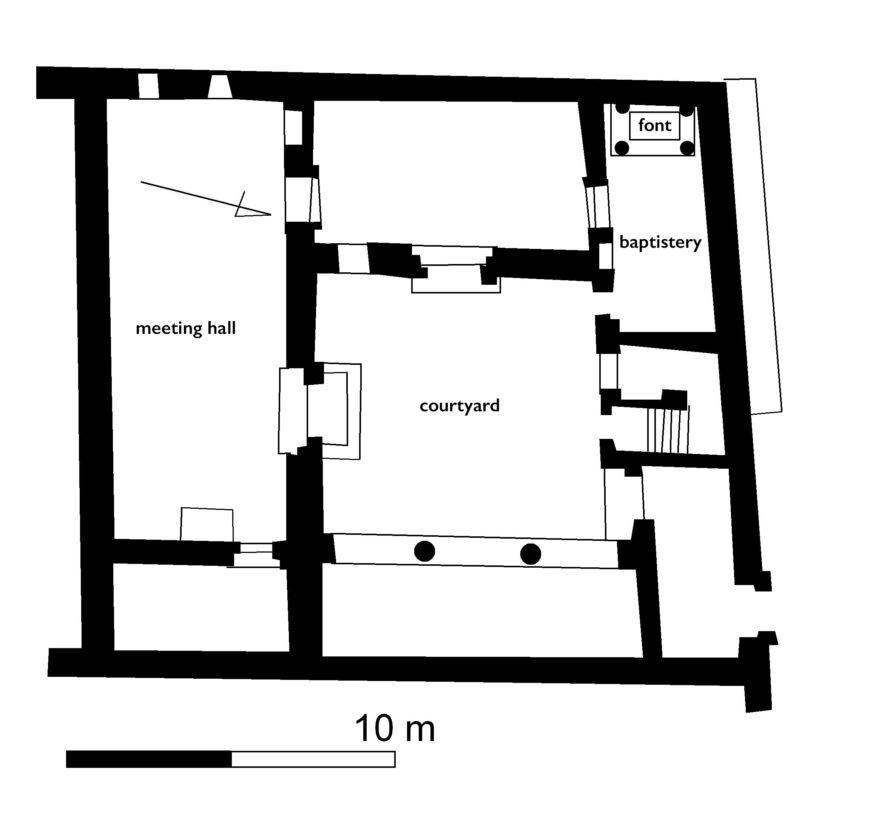

Roman catacombs, cubiculum with loculi (left), cubiculum with arcosolia (right), adapted from Antonio Bosio, Roma sotterranea, opera postuma di Antonio Bosio romano, antiquario ecclesiastico singolare de’ suoi tempi (Rome: 1632) (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

The earliest Christian burials at the Roman catacombs were situated amid those of other religions, but by the end of the second century, exclusively Christian cemeteries are known, beginning with the Catacomb of St. Callixtus on the Via Appia, c. 230. Originally well organized with a series of parallel corridors carved into the tufa (a porous rock common in Italy), the catacombs expanded and grew more labyrinthine over the subsequent centuries. Within, the most common form of tomb was a simple, shelf-like loculus organized in multiple tiers in the walls of the corridors. Small cubicula surrounded with arcosolium tombs provided setting for wealthier burials and provide evidence of social stratification within the Christian community.

Above ground, a simple covered structure provided a setting for the refrigeria, such as the triclia excavated beneath S. Sebastiano, by the entrance to the catacombs.

The development of a cult of martyrs with the early church led to the development of commemorative monuments, usually called martyria, but also referred to in texts as tropaia and heroa. Among those in Rome, the most important was the tropaion marking the tomb of St. Peter in the necropolis on the Vatican Hill.

Crypt of the Popes, Catacombs of Callixtus, Rome, 3rd century (photo: Dnalor 01, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Increasing visibility

By the time of the Tetrarchy, Christian buildings had become more visible and more public, but without the scale and lavishness of their official successors. In Rome, the meeting hall of S. Crisogono seems to have been founded c. 300 as a visible Christian monument. Similarly in Nikomedia at the same time, the Christian meeting hall was prominent enough to be seen from the imperial palace. Just as the administrative structure of the church and the basic character of Christian worship were established in the early centuries, pre-Constantinian building laid the groundwork for later architectural developments, addressing the basic functions that would be of prime concern in later centuries: communal worship, initiation into the cult, burial, and the commemoration of the dead.

Imperial patronage

The Colossus of Constantine, c. 312-15 (Palazzo dei Conservatori, Musei Capitolini, Rome) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

With Constantine’s acceptance of Christianity as an official religion of the Roman Empire in 313, he committed himself to the patronage of buildings meant to compete visually with their pagan counterparts. In major centers like Rome, this meant the construction of huge basilicas capable of holding congregations numbering into the thousands. Although the symbolic associations of the Christian basilica with its Roman predecessors have been debated, it thematized power and opulence in ways comparable to but not exclusive to imperial buildings.

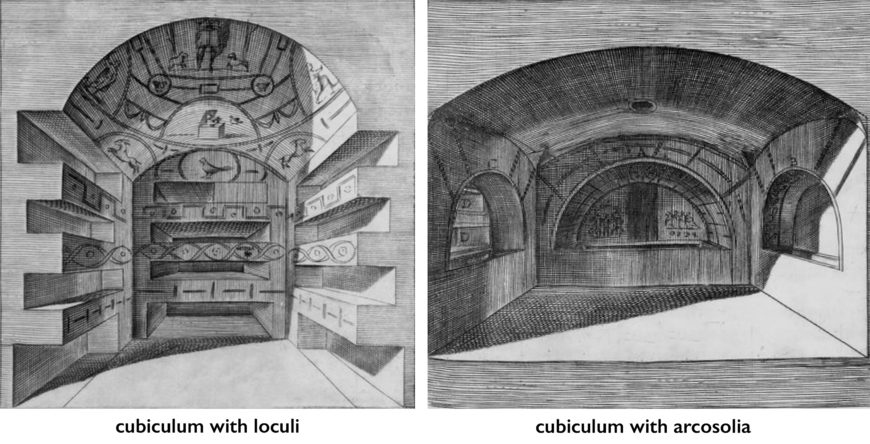

Elements of a Christian basilica, adapted from illustration of S. Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna, in Banister Fletcher, A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method, 6th ed. (London: B. T. Batsford, 1921)

Relief with Marco Aurelius sacrificing to Jupiter (Pietas Augusti) with a temple in the background, from the decoration of a triumphal arch, 177-180 C.E. (Capitoline Museums, Rome) (photo: MatthiasKabel, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Formally, the basilica also stood in sharp contrast to the pagan temple, at which worship was conducted out of doors. The church basilica was essentially a meeting house, not a sacred structure, but a sacred presence was created by the congregation joining in common prayer—the people, not the building, comprised the ekklesia (the Greek word for “church”).

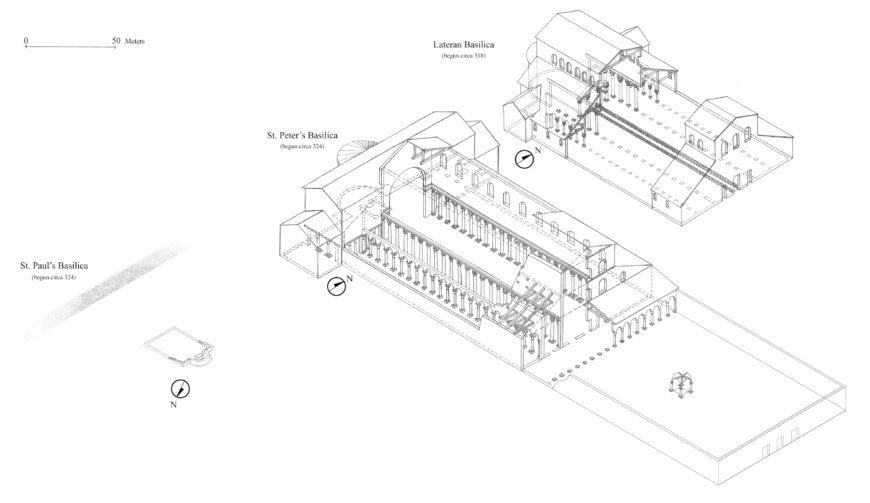

The Lateran basilica, originally dedicated to Christ, was begun c. 313 to serve as Rome’s cathedral, built on the grounds of an imperial palace, donated to be the residence of the bishop. Five-aisled in plan, the basilica’s tall nave was illuminated by clerestory windows, which rose above coupled side aisles along the flanks and terminated in an apse at the west end, which held seats for the clergy. Before the apse, the altar was surrounded by a silver enclosure, decorated with statues of Christ and the Apostles.

Comparative view of the Constantinian basilicas at St. Paul’s, St. Peter’s, and at the Lateran. Model of St. Paul’s by Evan Gallitelli. Image by Evan Gallitelli includes drawings by Konstantin Brandenburg published in Hugo Brandenburg’s Ancient Churches of Rome from the Fourth to the Seventh Century (Turnhout: Brepols, 2004), fig. 1. (© Nicola Camerlenghi)

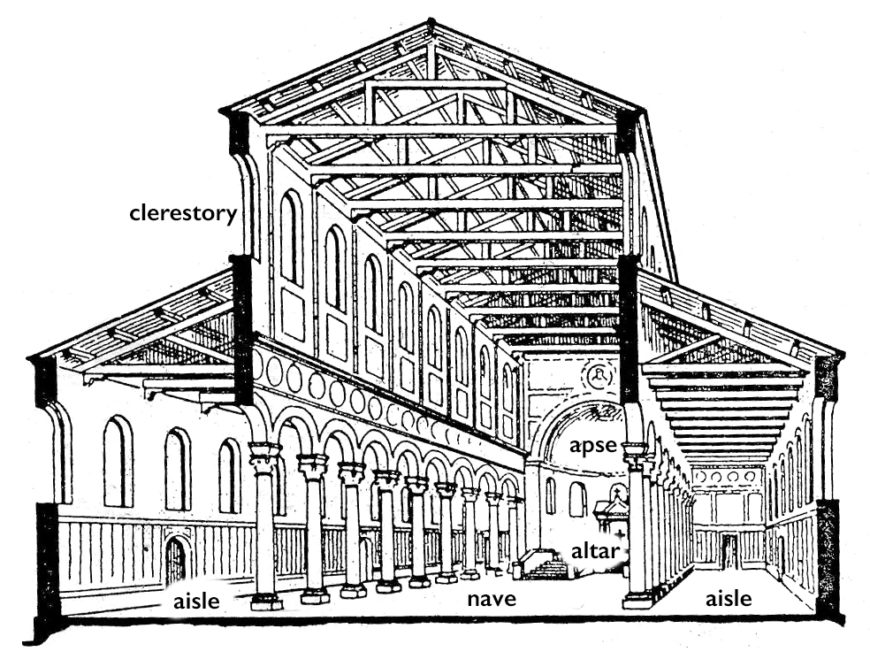

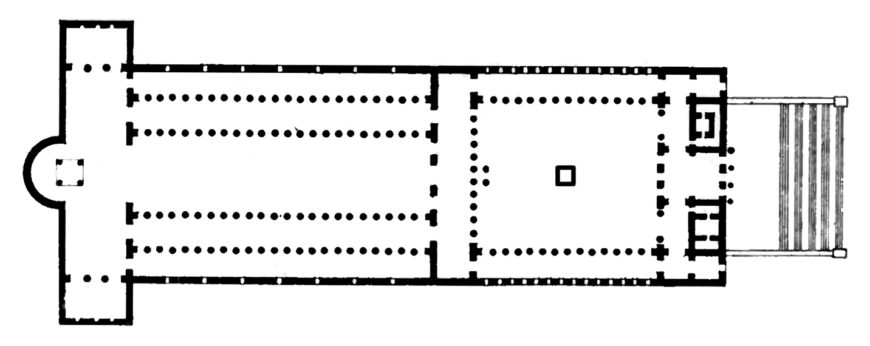

In addition to congregational churches, among which the Lateran stands at the forefront, a second type of basilica (or ambulatory basilica) appeared in Rome at the same time, set within the cemeteries outside the city walls, apparently associated with the venerated graves of martyrs. S. Sebastiano, probably originally the Basilica Apostolorum, which may have been begun immediately before the Peace of the Church, rose on the site of the earlier triclia, in which graffiti testify to the special veneration of Peter and Paul at the site. These so-called cemetery basilicas provided a setting for commemorative funeral banquets. Essentially covered burial grounds, the floors of the basilicas were paved with graves and their walls enveloped by mausolea.

In plan they were three-aisled, with the aisle continuing into an ambulatory surrounding the apse at the west end. By the end of the fourth century, however, the practice of the funerary banquet was suppressed, and the grand cemetery basilicas were either abandoned or transformed into parish churches.

Martyria

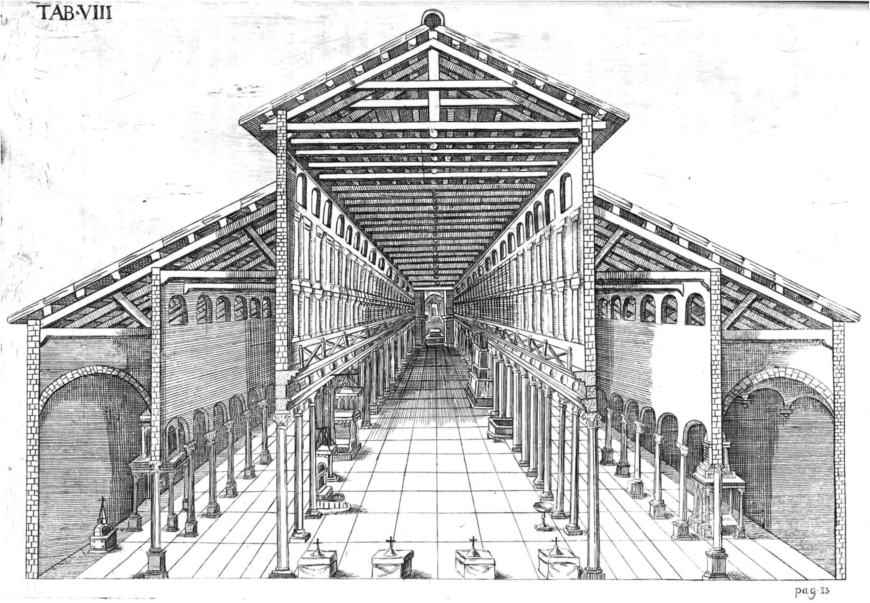

Constantine’s St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome, from: Giovanni Ciampini, De sacris aedificiis a Constantino Magno constructis: synopsis historica, 1693, p. 33

Ciborium of Old St. Peter’s, Werro, Itinerarium von der saeligen Reise gegen Romeund Jerusalem im Jahr 1581 (Fribourg, Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire, ms. L 181, f. 16v)

Constantine also supported the construction of monumental martyria.

Most important in the West was St. Peter’s basilica in Rome, begun c. 324, originally functioning as a combination of cemetery basilica and martyrium, sited so that the focal point was the marker at the tomb of Peter, covered by a ciborium (canopy) and located at the chord of the western apse. The enormous five-aisled basilica served as the setting for burials and the refrigeria. To this was juxtaposed a transept—essentially a transverse, single-aisled nave—which provided access to the saint’s tomb. The eastern atrium seems to have been slightly later in date.

Reconstructed plan of Constantine’s St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome, c. 320, adapted from Banister F. Fletcher, A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method, 5th ed. (London: B. T. Batsford, 1905).

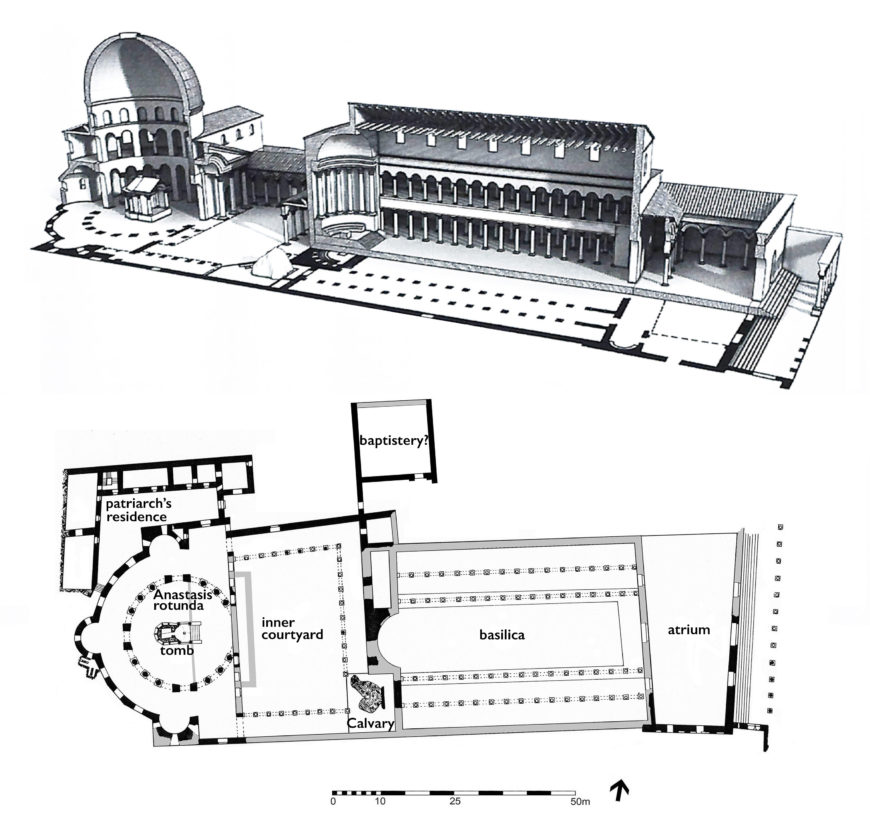

In the Holy Land, major shrines similarly juxtaposed congregational basilicas with centrally-planned commemorative structures housing the venerated site. At Bethlehem (c. 324), a short five-aisled basilica terminated in an octagon marking the site of Christ’s birth. At Jerusalem, Constantine’s church of the Holy Sepulchre (dedicated 336) marked the sites of Christ’s Crucifixion, Entombment, and Resurrection, and consisted of a sprawling complex with an atrium opening from the main street of the city; a five-aisled, galleried congregational basilica; an inner courtyard with the rock of Calvary in a chapel at its southeast corner; and the aedicula of the Tomb of Christ, freed from the surrounding bedrock, to the west. The Anastasis Rotunda, enclosing the Tomb aedicula, was completed only after Constantine’s death.

Restored plan and hypothetical section, church of the Holy Sepulchre, c. 350 C.E. (© Robert G: Ousterhout and Tayfun Öner)

Most martyria were considerably simpler, often no more than a small basilica. At Constantine’s Eleona church on the Mount of Olives, for example, a simple basilica was constructed above the cave where Christ had taught the Apostles.

Pilgrims’ accounts, such as that left by the Spanish nun Egeria (c. 380), provide a fascinating view of life at the shrines. These great buildings played an important role in the development of the cult of relics, but they were less important for the subsequent development of Byzantine architecture.

New Rome

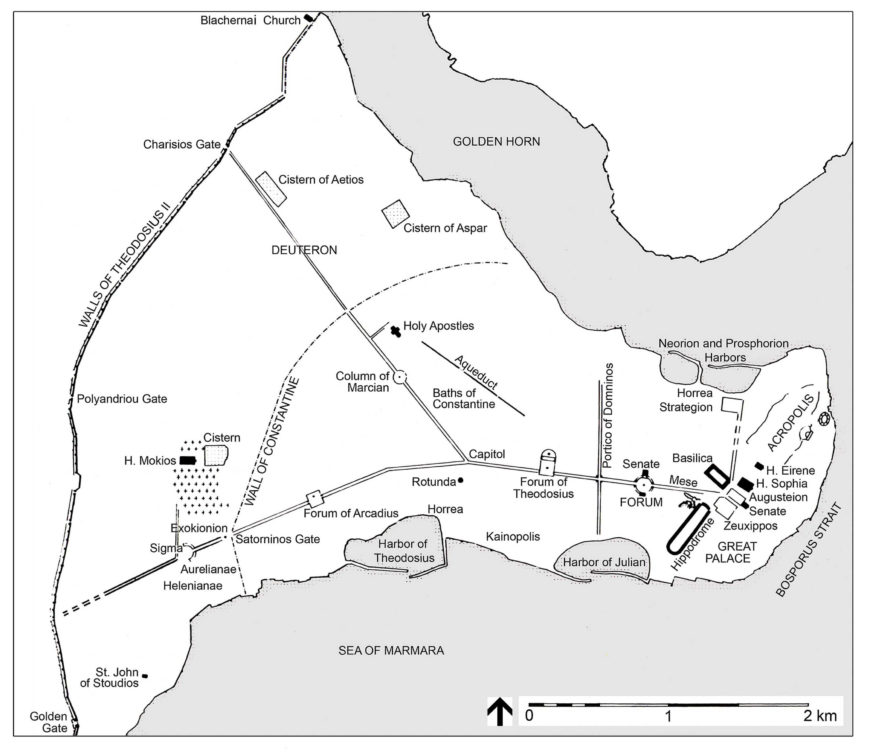

In addition to his acceptance of Christianity, Constantine’s other great achievement was the establishment of a new imperial residence and subsequent capital city in the East, strategically located on the straits of the Bosphorus. Nova Roma or Constantinople, as laid out in 324-330, expanded the urban armature of the old city of Byzantion westward to fill the peninsula between the Sea of Marmara and the Golden Horn, combining elements of Roman and Hellenistic city planning.

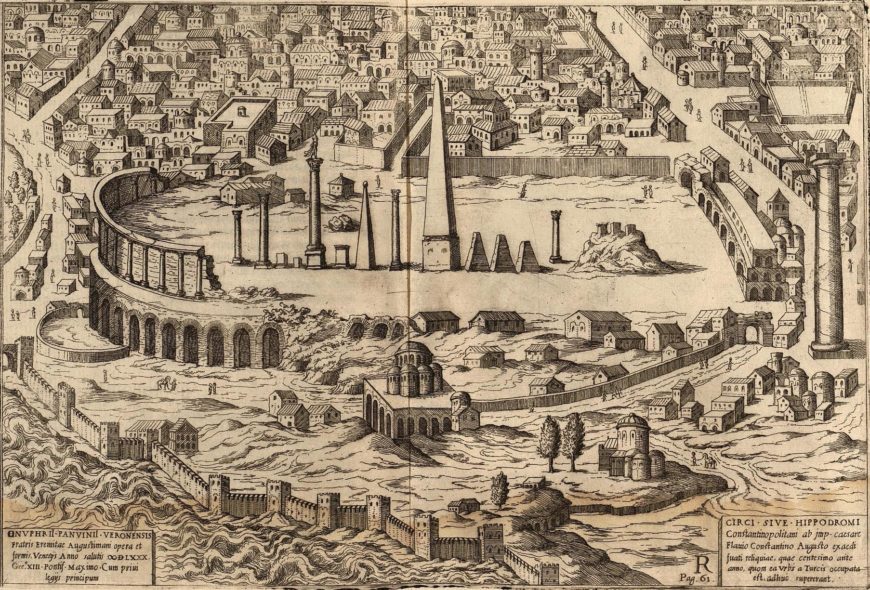

Like old Rome, the new city of Constantine was built on seven hills and divided into fourteen districts; its imperial palace lay next to its hippodrome, which was similarly equipped with a royal viewing box. As in Rome, there were a senate house, a Capitol, great baths, and other public amenities; imperial fora provided its public spaces; triumphal columns, arches, and monuments, including a colossus of the emperor as Apollo-Helios, and a variety of dedications imparted mimetic associations with the old capital.

Constantinople, plan of the fifth century city (© Robert G. Ousterhout, based on Cyril Mango, Développement urbaine de Constantinople, 1985)

Constantine’s own mausoleum was established in a position that encouraged a comparison with that of Augustus’s mausoleum in Rome; the adjoining cruciform basilica—the church of the Holy Apostles—was apparently added by his sons. Beyond the much-altered porphyry column that once stood at the center of his forum, however, virtually nothing survives from the time of Constantine; the city continued to expand long after its foundation.

Ruins of the hippodrome in Constantinople, c. 1560, engraving by Étienne Dupérac, for Onofrio Panvinio, De ludis circensibus, 1600, probably based on a late 15th century drawing (photo: Paul K, CC BY 2.0)

Next: read about Early Byzantine architecture after Constantine

Additional Resources

Smarthistory’s free Guide to Byzantine Art e-book

Robert G. Ousterhout, Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019)