San Miniato al Monte, Florence, begun 1013 (photo: Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Map of Roman roads on the Italian peninsula (source: Eric Gaba, Agamemnus, Flappiefh, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Before the Italian peninsula was unified into a single nation in the nineteenth century, it was divided into numerous separate countries, papal-controlled territories, and city states with constantly shifting boundaries. Unlike regions north of the Alps, in Italy the durable old Roman roads that snaked down the length of the peninsula were preserved by mild weather and continuous use. The former Roman cities along these roads became hubs of trade. These included Florence on the Via Cassia between Rome and the old central Italian heartland, and Pisa, on the Via Aurelia between Rome and what was known as “Roman Gaul” (today France and Belgium).

Roman walls, aqueducts, monuments, and buildings dotted the landscape, and this Roman heritage profoundly impacted the appearance of the region’s churches. During the middle ages, residents of the cities of Tuscany valued their Roman past, particularly as it was associated with the origins of institutional Christianity. Although Tuscany was a duchy and controlled by the Canossa family, in reality the cities of Tuscany soon established their own governments and civic identities.

Florence and Pisa are wonderful examples of this. During the eleventh century, each city’s Roman heritage was still visible in the form of roads and bridges, walls and cemeteries, but each city also took on its own character based on the preferences of its inhabitants and the sources of their economic strength. The architecture of San Miniato in Florence and the Cathedral of Pisa visibly express both their unique regional and civic qualities, as well as links to the Roman past.

A monastery on a hill

The church of the Benedictine monastery of San Miniato al Monte (above) lies outside the early medieval walls and across the Arno from Florence. It hovers over the city on the crest of a hill, or “monte,” where Florentines believed the cell of Saint Minias, an Armenian Christian hermit who was allegedly martyred by the Roman Emperor Decius in the third century, once stood. By 1018, the bishop of Florence had ordered the construction of a church and installed a community of Benedictine monks there, following a familiar medieval pattern of locating monasteries outside, but within a short distance of, a city so that the monks could minister to the spiritual needs of the city’s inhabitants.

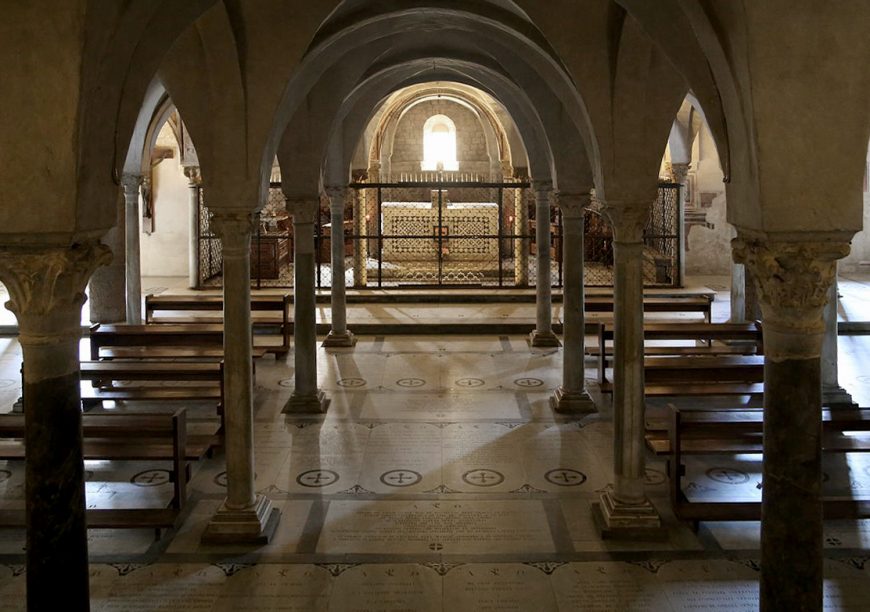

Crypt (below the high altar), San Miniato al Monte, Florence, begun 1013 (photo: Rufus46, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A synthesis of forms

View down the nave toward the raised chancel. Wooden trusses are visible above and diaphram arches can be seen spanning the width of the nave. San Miniato al Monte, Florence, begun 1013 (photo: Waldstein, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The builders cleverly designed the church so that it could accommodate visitors to the tomb of Minias. Adapting a basilica-style structure with its single apse and a trussed timber roof, the builders incorporated an innovative raised chancel. Central stairways allow visitors to see and visit the crypt housing Minias’s relics, while flanking stairways lead to an elevated platform holding the altar and choir used by the monks.

Corinthian capital, San Miniato al Monte, Florence, begun 1013 (photo: Rufus46, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A similar synthesis of ancient, Early Christian, and medieval forms is visible in the church’s walls. An arcade of polished stone columns supporting Corinthian capitals march down the nave, above which colorful stone inlay brightens the surface—all reminiscent of Early Christian basilicas like Santa Sabina in Rome. Many of the capitals are Roman spolia, noticeable because they are much narrower than the columns they crown.

The roots of Florentine style

Yet onto this traditional framework the builders grafted imposing diaphragm arches that divide the nave into three massive bays, marked on the walls with attached columns and compound piers. The green and white stone inlay familiar from some Early Christian interiors clads the surfaces of the façade and the interior (though in some places, after money ran out, artists imitated the decorative stone in paint). This style of construction, joining modified basilican architecture with colorful, two-dimensional stone inlay, would become typical of the Florentine region.

San Miniato al Monte, Florence, begun 1013 (photo: Rufus46, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The façade also references the Roman past. Although the component parts are flattened and rendered in pink, green and white stone, we can still identify an orderly row of columns topped by Corinthian capitals, crowned by a set of four Corinthian pilasters holding a triangular pediment that recalls a Roman temple front. In the fifteenth century, the Renaissance architect Leon Battista Alberti, would use many of the same elements in crafting the typically Tuscan façade of Santa Maria Novella, across town.

Baptistery, cathedral, and campanile, Piazza dei Miracoli, Pisa, 11th-12th century (photo: Massimo Catarinella, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Pisa and its “Leaning Tower”

Campanile (bell tower), Piazza dei Miracoli, Pisa, begun 1173 (photo: Nikolai Karaneschev, CC BY 3.0)

The Arno, the river that flows through Florence, eventually reaches the city of Pisa on its way to the Mediterranean Sea. In the Middle Ages, before the river’s silt deposits pushed the sea away, Pisa was located very near the coast. It was an important port city from Roman times onwards, and by the eleventh century it became a maritime republic (a city-state whose economic base was maritime trade), competing with the other Italian naval powerhouses like Genoa, Venice, and Amalfi to dominate Mediterranean trade. Pisa warred constantly with rival maritime powers in Corsica, Sicily, North Africa and on the Italian mainland. The cathedral for which it is now famous was built starting in 1063, in the wake of, and using booty from, Pisa’s naval victory over Palermo.

Like most cathedrals on the Italian peninsula, Pisa’s was built as an assemblage of freestanding buildings, including a baptistery and bell tower (campanile) in addition to the church. The Pisa cathedral complex was unusual, however, in that it was situated well outside the city walls in a grassy precinct that incorporated an ancient cemetery. Surrounded by the marshes of the Arno, the precinct’s damp soil contributed to unstable ground under the complex’s key structures, most noticeable in the campanile, which began to lean even while it was still being built in the twelfth century.

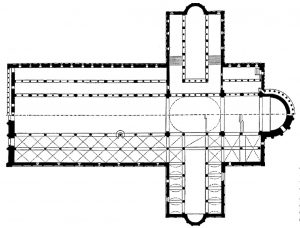

Plan of Pisa Cathedral, begun 1063, from Georg Dehio, Die kirchliche Baukunst des Abendlandes (1887), plate 68 (Heidelberg University Library)

Old meets new

Pisa Cathedral, like San Miniato, borrows heavily from the architectural past. It has a basilica footprint with double aisles separated from the nave by colossal Corinthian columns, a trussed timber roof, and a single semicircular apse, all perhaps intended to recall Old St. Peter’s in Rome. Each of the arms of the transept repeats this basic formula on a smaller scale, with single aisles flanking a central space that leads to a smaller apse, creating a four-armed groundplan. This and the substantial galleries below clerestory windows recall the basilicas of the early Byzantine east.

Interior, Pisa Cathedral, begun 1063 (photo: Tango7174, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The builders also added new features. Above the arcade and galleries and between the clerestory windows one finds expanses of cream and green striped wall. Although the pattern here is different from that found on the walls of San Miniato in Florence, both share the same complexity and conspicuous display of expensive materials.

An unusual dome

Although they probably originally planned a simpler wooden covering for the crossing, by the end of the eleventh century the builders had begun to construct a dome, perhaps to keep pace with contemporary domes built north of Tuscany in Lombardy, or even by Pisa’s economic rival, Venice. The unusual and complicated elliptical shape was dictated by the rectangular outline of the crossing created by the meeting of the nave, choir and transepts. The builders bridged the corners of this opening under the dome’s base with Byzantine-inspired squinches that resemble those built at Hosios Loukas in Greece just a few years before. Above the squinches, subtlely incised blind arcades can be seen. The colorful fresco depicting the Assumption of the Virgin was added in the 17th century.

A virtual Holy Land

Pisa Cathedral, begun 1063 (photo: Stefan Lew, CC 0)

Most impressive to medieval visitors would have been the exterior. The simple geometry of the façade immediately recalls San Miniato’s stack of rectangles and triangles, all resting on a shallow arcade with Corinthian capitals that frame three doors. At Pisa, though, above the ground floor, the façade becomes dramatically three-dimensional, with open arcades that screen a wall decorated with grey and white stripes.

Pisa Cathedral, begun 1063 (photo: © José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro / CC BY-SA 3.0)

On the church’s sides, transept, and apse, the grey and white stone has been embellished with blind arcades and colonnades (rows of columns). Lozenges, roundels, and rectangles of multicolored stone inlay dot the exterior.

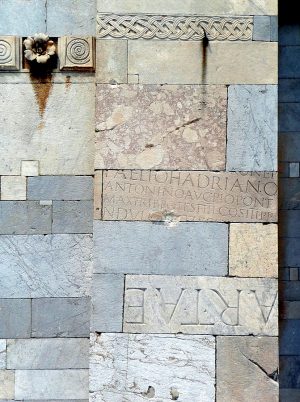

Spolia on the exterior of Pisa Cathedral (photo: Lucarelli, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Reused stones covered with inscriptions and sarcophagi imported from Rome are inserted seemingly at random: a testimony to the builders’ desire to invent an ancient heritage for the building and demonstrate the wealth and power of Pisa.

The other buildings in the complex, built starting in the twelfth century after the Pisan navy participated in the First Crusade, complete this sumptuous display. The centrally-planned, domed baptistery may have been intended to imitate the church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. It and the leaning campanile are completely encased in stacked arcades, mirroring those on the cathedral. The “Camposanto,” an enclosed cemetery, was filled with earth imported from the Holy Land in the holds of Pisan ships. Pisans may have imagined this collection of buildings, with its many references to ancient Christian sites, as a virtual Holy Land, a site they were then trying to reconquer.

Each a product of its particular region, San Miniato and Pisa Cathedral speak to the ways that medieval builders sought to express their cities’ unique identities through both ancient allusions and innovative forms.

Additional resources:

San Miniato al Monte on Google Arts and Culture

Plan and elevation of San Miniato al Monte at the Courtauld Institute

Piazza del Duomo, Pisa on the UNESCO World Heritage website

Photos and 3-D models of Piazza del Duomo from CyArk

Diane Cole Ahl, “Camposanto, Terra santa: Picturing the Holy Land in Pisa,” Artibus et Historiae 24 (2003), pp. 95-122.

Kenneth John Conant, Carolingian and Renaissance Architecture 800-1200 (New York: Penguin, 1978), pp. 372-382.