Sutton Hoo and Europe 300–1100 C.E., The Sir Paul and Lady Ruddock Gallery © The Trustees of the British Museum

The most famous Anglo-Saxon treasures in the Museum come from the Sutton Hoo burial site in Suffolk. Here mysterious grassy mounds covered a number of ancient graves. In one particular grave, belonging to an important Anglo-Saxon warrior, some astonishing objects were buried, but there is little in the grave to make it clear who was buried there.

Sutton Hoo

On a small hill above the river Deben in Suffolk is a strange-looking field, covered with grassy mounds of different sizes. For several hundred years what lay under them was a mystery.

Left: Painted portrait of Edith Pretty (© British Museum); Right: Basil Brown (photo: Suffolk Archaeological Unit)

In 1939 Mrs Edith Pretty, a landowner at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk, asked archaeologist Basil Brown to investigate the largest of several Anglo-Saxon burial mounds on her property. Inside, he made one of the most spectacular archaeological discoveries of all time. Brown started digging under mounds 2, 3 and 4, where he found a few, mostly broken, Anglo-Saxon objects which had been buried alongside their owner’s bodies. Sadly, grave robbers had taken most of what was there. With a little more hope he started on the biggest mound, Mound 1. He did not know that the treasures under Mound 1 would turn out to be the most amazing set of Anglo-Saxon objects ever found.

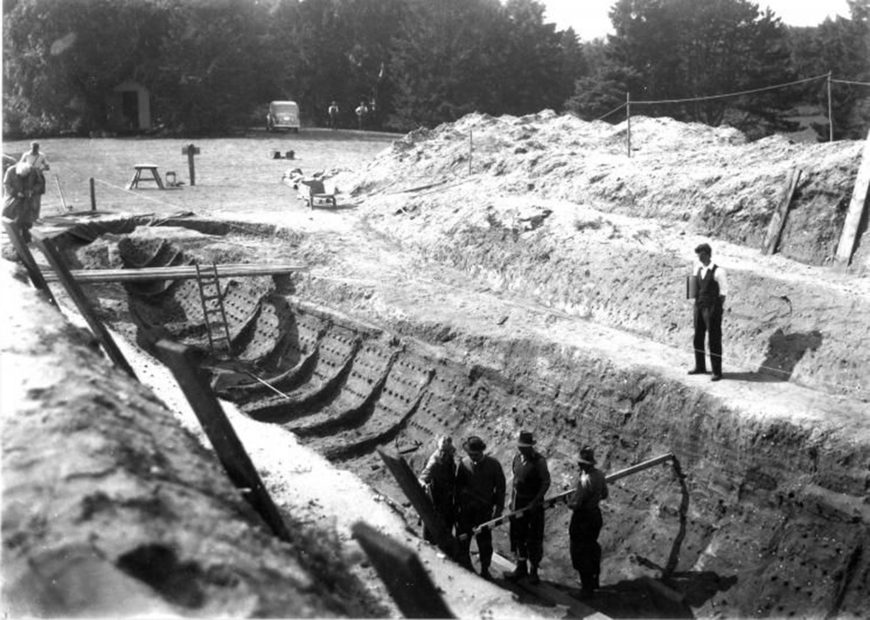

Excavation of the Sutton Hoo ship burial, 1939 (photo: Barbara Wagstaff, © 2019 The Trustees of the British Museum)

Beneath the mound was the imprint of a 27-metre-long ship. At its centre was a ruined burial chamber packed with treasures: Byzantine silverware, sumptuous gold jewelry, a lavish feasting set, and most famously, an ornate iron helmet. Dating to the early 600s, this outstanding burial clearly commemorated a leading figure of East Anglia, the local Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It may even have belonged to a king.

Belt Buckle, Sutton Hoo, early 7th century, gold, 13.2 x 5.6 cm © Trustees of the British Museum

Gold coins and ingots from the ship burial at Sutton Hoo, early 7th century, Sutton Hoo, Suffolk, England © Trustees of the British Museum.

The burial can only be dated on the basis of the coins that were found there. There was a purse among the burial goods, which contained 37 gold coins, 3 coin-shaped blanks, and 2 small gold ingots. The presence of the coin-shaped blanks suggests that the number of coins was deliberately rounded up to 40. The coins cannot be dated closely, but seem to have been deposited at some point between around 610-635. They all come from the kingdom of the Merovingian Franks on the Continent, rather than any English kingdom, although coin production had started in Kent by this time. Sutton Hoo was in the kingdom of East Anglia and the coin dates suggest that it may be the burial of King Raedwald, who died around 625.

The Sutton Hoo ship burial provides remarkable insights into early Anglo-Saxon England. It reveals a place of exquisite craftsmanship and extensive international connections, spanning Europe and beyond. It also shows that the world of great halls, glittering treasures and formidable warriors described in Anglo-Saxon poetry was not a myth.

Mrs Edith Pretty donated the finds to the British Museum in 1939.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”suttonhoo,”]