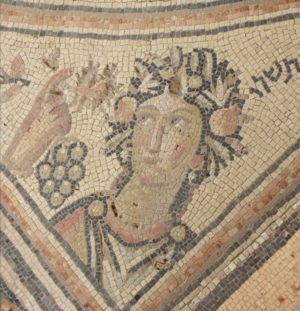

Sol, Hammath Tiberias Synagogue, 286–337 C.E. (Center for Jewish Art)

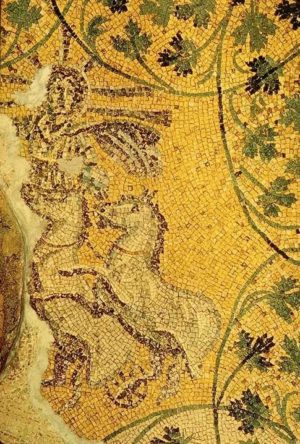

Tiny cube-shaped pieces of cut stone and glass combine to form a mosaic image of a god, a beautiful young male with curly hair and a radiant crown of seven rays of light. He raises his right hand as if signaling his mastery of the cosmos. In his left hand, he holds an orb (representing the sun) and a whip to urge his horses forward. He once stood in a quadriga, a chariot pulled by four horses, now destroyed by the later addition of a wall, though their hooves can still be seen. This 4th-century mosaic depicts the indomitable Roman sun god Sol, known in Greek as Helios.

Sol and empire

Sol became an especially popular solar deity in the later Roman Empire. There was a long imperial tradition of worshiping the sun god, and by the 3rd century, emperors frequently associated themselves with Sol, referring to the god with the epithet “Invictus,” meaning invincible. As the Roman emperors expanded their territory and defended their borders, the sun god’s attributes of eternity and dominion proved an irresistible model for representing imperial triumph. As a result, the image of Sol Invictus frequently appeared in imperial coinage and monuments.

The early fourth-century emperor Constantine I was a particularly fervent adherent of the cult of the sun. Nearly three-quarters of his coinage included portraits of himself with Sol’s rayed crown and raised right hand, and the inscription SOLI INVICTO COMITI (to the invincible sun, companion [of the emperor]).Roman coin of Constantine I with Sol Invictus on the reverse, 307–318 C.E. (Anja Rohde, CC BY-SA 4.0)

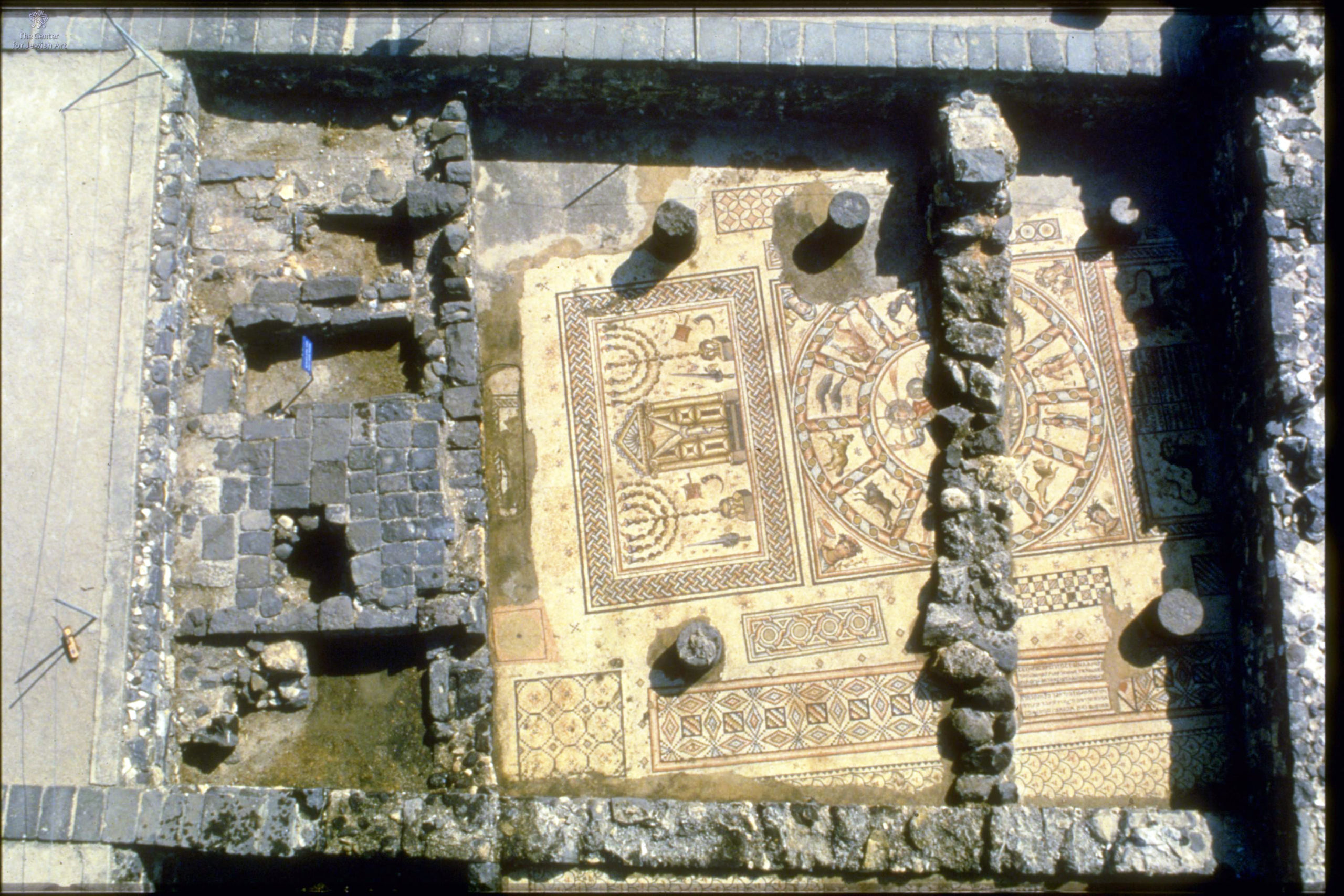

Hammath Tiberias Synagogue, 286–337 C.E. (Zev Radovan, 1994, Center for Jewish Art)

In Hammath Tiberias, the personified sun god appears at the center of a large mosaic floor divided into three panels featuring dedicatory inscriptions, personifications of the seasons and the twelve signs of the zodiac, and motifs associated with the ancient Jewish Temple in Jerusalem. What prompted the fourth-century Jewish community of Hammath Tiberias, a monotheistic community, to adorn their house of worship with an image of Sol, a prominent Roman deity? The mosaics of Hammath Tiberias can only be understood in the context of Late Antique and early Byzantine Jewish history and culture, Greco-Roman and early Christian artistic traditions, and the dramatic political, religious, and social circumstances of the 4th through 7th centuries.

Roman expansion and religious pluralism in the eastern Mediterranean

From the early days of the Roman Republic on, the Romans continuously expanded their territory as they came into conflict with surrounding city-states, kingdoms, and empires. By the second century C.E., the Roman Empire had reached its greatest extent, with its territory stretching across modern-day western Europe, north Africa, and western and central Asia. Judea (the Land of Israel) was among the many new regions conquered by the Romans, including the city of Tiberias, founded by Roman Emperor Herod Antipas in 19–20 C.E. on the fertile shores of the Sea of Galilee. To its south lies a small suburb, Hammath Tiberias, well known for its therapeutic baths fed by natural hot springs.

As the Romans conquered Judea and other territories, for the most part, these new cities and regions were allowed to maintain their existing cultural and political institutions. Although religious practice of the Roman Empire centered on the pantheon of Roman gods, the Jewish communities living in the Roman-controlled Judea and in the Diaspora were permitted freedom of religious worship. This likewise extended to other religious communities, such as Zoroastrians, and Christians, among others, living in the territories of the Roman Empire.

Having lived under Roman rule from at least the 2nd century B.C.E., the Jewish population had acculturated and developed a deep knowledge and appreciation of Greco-Roman traditions and artistic forms. Alongside reading Hebrew, the language of the Hebrew Bible, and speaking and writing in Aramaic, the literary and spoken language of the Jewish community in the land of Israel, many Jews also spoke and wrote in Greek, widely used throughout the Roman Empire.

Left: terracotta oil lamp with Sol, Cyprus, c. 75–125 C.E. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); middle: terracotta oil lamp with chi-rho, Cyprus, 4th-5th century C.E. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); terracotta oil lamp with menorah, c. 375–500 C.E., Carthage, Tunisia (The British Museum)

Beginning in the 4th century, the Eastern Mediterranean underwent a period of dramatic political, economic, and cultural change, including the rapid Christianization of the region. As the religious majority changed, Jews and Christians lived side by side, in dialogue and in competition. This was especially the case in their artistic output. Jews and Christians drew upon a common visual language that emerged out of the dominant Roman visual tradition. Although they shared art forms, materials, and techniques, they adapted these elements to express their own theologies and histories. For example, clay oil lamps dating to the 2nd through 4th centuries reflect this shared heritage—some oil lamps display Roman deities, such as the sun god Sol, while others include Christian symbols such as the chi-rho, or Jewish symbols, such as the menorah. As much as artistic production reflected their collective cultural experience, it also became an indispensable tool for each religious community to define itself vis-a-vis the other.

Hammath Tiberias synagogue, 286–337 C.E., Israel (Brad Erickson, CC BY-NC 4.0)

The Hammath Tiberias mosaics

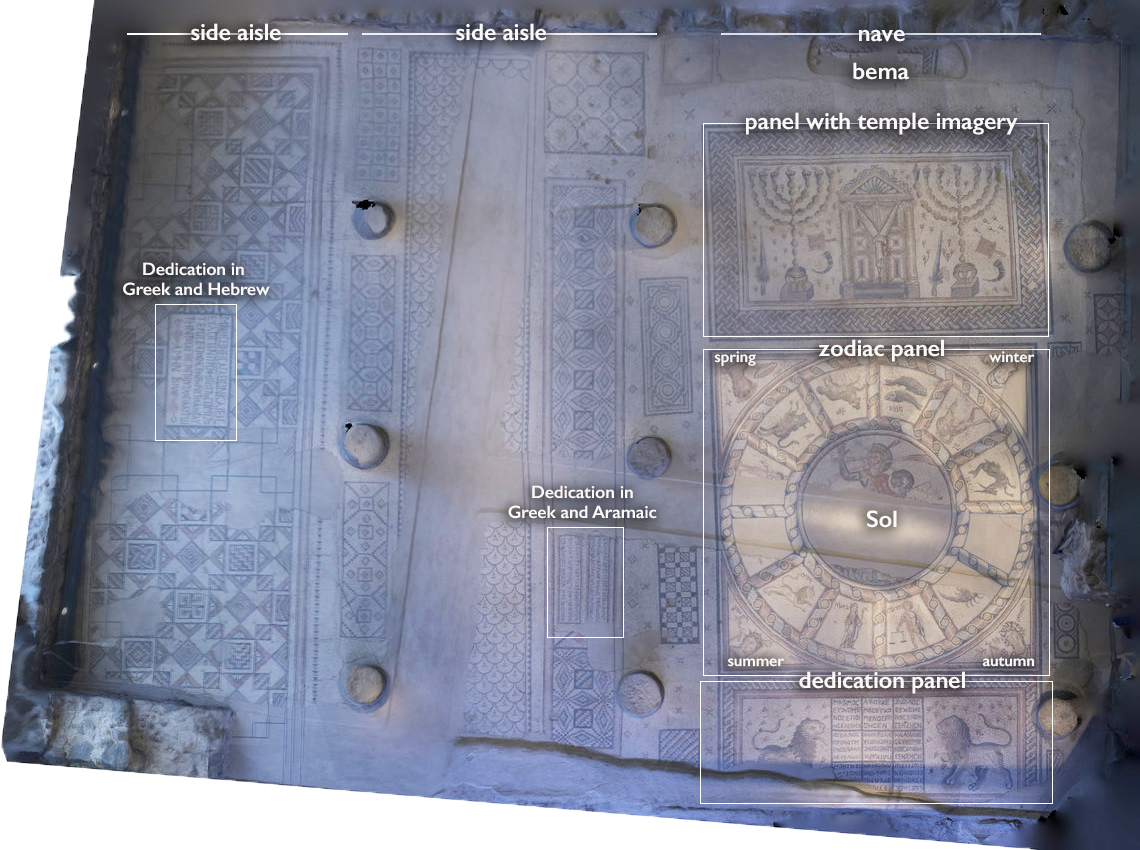

Located on a bluff overlooking the Sea of Galilee, the Hammath Tiberias synagogue was built in the first half of the 3rd century following a basilica plan with a central nave and two side aisles, a layout commonly used for Roman public buildings. Following its partial destruction by an earthquake in 306 C.E., the local residents renovated the synagogue, retaining much of its original structure, while also outfitting it with a new mosaic floor.

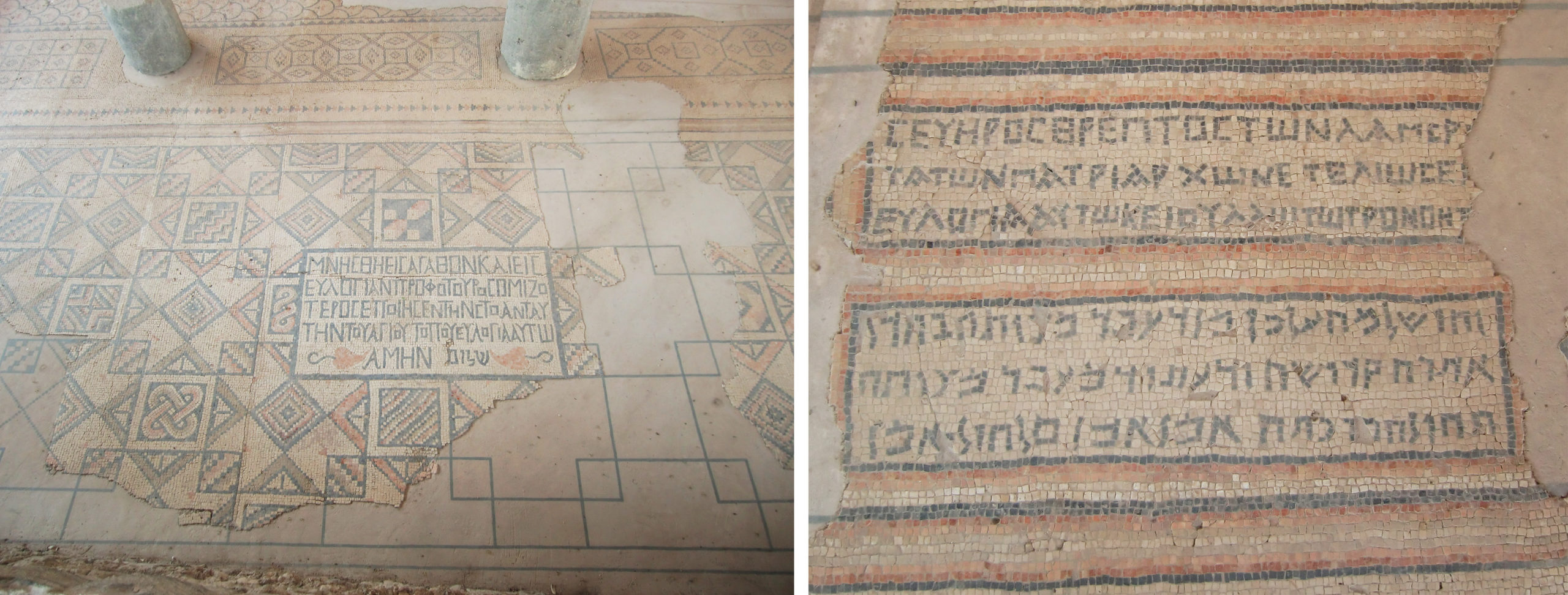

Left: Greek dedicatory inscription; right: Greek and Aramaic dedicatory inscriptions, side aisles, Hammath Tiberias, 286–337 C.E. (Manar al Athar)

Upon entering from the east, worshippers encountered three dedicatory inscriptions, two in Greek and one in Aramaic naming the synagogue’s main donors and blessing other members of the community who had or would donate to the synagogue. Several inscriptions mention “Severos, student of the illustrious patriarch,” suggesting that the synagogue may have been closely aligned with the Patriarchate, which acted as the official channel of communication between the Roman Empire and its Jewish subjects. With their ties to the patriarch, the reconstruction and lavish decoration of the synagogue would have offered Severos and other local elites the opportunity to communicate their wealth, power, and distinctly Jewish identity to a broader public.

Panel with Greek dedicatory inscriptions, Hammath Tiberias, 286–337 C.E. (Manar al Athar)

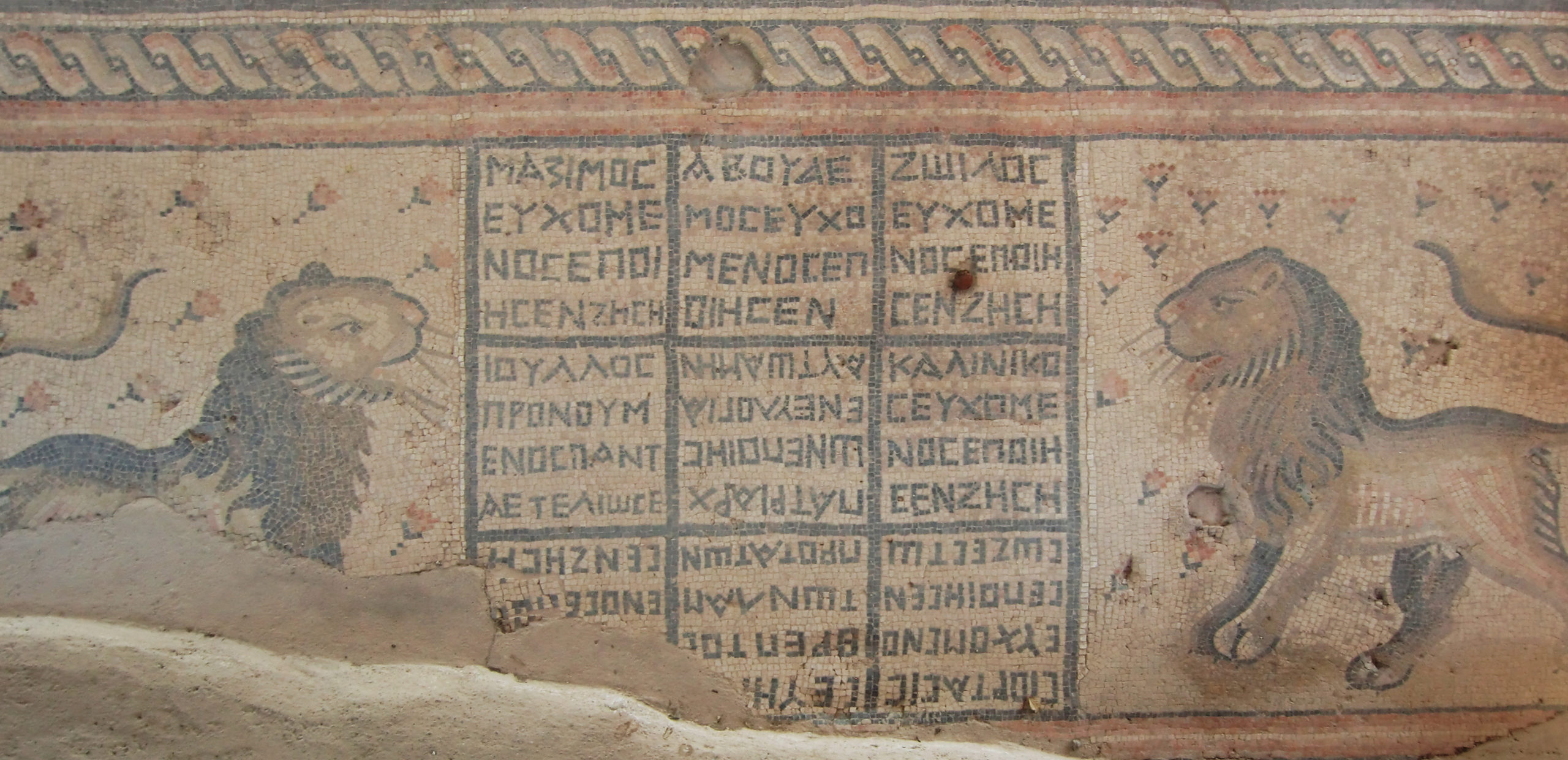

The mosaics of the side aisles, although mostly destroyed, contained continuous geometric patterns and dedicatory panels. In contrast, the mosaics of the nave are divided into three panels featuring figural imagery. To the north, a pair of mosaic lions flank a dedicatory panel, divided into nine squares and inscribed in Greek with the names of the synagogue’s donors, including two squares devoted to the patronage of Severos.

Personifications of the four seasons, zodiac, and Sol, Hammath Tiberias, 286–337 C.E. (fabcom)

Personification of Autumn, Hammath Tiberias, 286–337 C.E. (Manar al Athar)

The center of the room features a large panel with personifications of the seasons labeled in Hebrew in each of its four corners. Each of the personifications bears attributes representing the agricultural activities of the season: Spring for example wears a sleeveless tunic, a wreath of flowers, and carries a bowl of flower buds; Autumn wears a wreath of leaves with figs and pomegranates and carries a vine branch with grapes and possibly olives, symbolizing the fall harvest.

These personifications frame two concentric circles that contain images of the twelve astrological signs of the zodiac in the outer circle, also labeled in Hebrew, with the sun god Sol in the inner circle. Like Sol, the form of the zodiac and its individual figures draw on contemporary Roman artistic traditions. The astrological sign for Virgo, for example, appears similar to the goddess Kore-Persephone, whose cult was popular in Roman Israel.

Mosaic panel with Temple imagery, Hammath Tiberias, 286–337 C.E. (Manar al-Athar)

At the southern end of the synagogue, a bema (raised platform) with a Torah ark (an architectural shrine housing the Torah scrolls), demarcated the sacred locus of the synagogue. Just before the bema, is a mosaic image of the ancient Temple in Jerusalem. At its center is an architectural façade, with two wooden doors covered by a curtain (the parochet, the curtain described in the Hebrew Bible as hanging before the Ark of the Covenant). It is flanked by two large menorot, or seven-branched candelabras, as well as smaller depictions of the lulav and etrog, shofar, and incense shovels—all objects derived from the rituals of the ancient Temple.

Detail of personifications of the four seasons, zodiac, and Sol, Tzippori synagogue, Galilee, 5th century C.E. (Manar al-Athar)

The mosaic floors, with their combination of Jewish religious imagery and motifs adapted from Greco-Roman traditions, powerfully evoked the sacred atmosphere of the ancient synagogue. While the mosaics at Hammath Tiberias are the first known instance of this iconography, this composition, with its imagery of the ancient Temple and vision of sacred time, clearly presented a compelling message for the Jewish community. Variations with the zodiac, temple implements, and biblical scenes, which further emphasize God’s covenant with the Jewish people, appear in five later extant synagogue floors across northern Israel, all dating to the 5th and 6th centuries: Beth Alpha, Huseifa, Susiya, Na’aran, and Tzippori.

Sol, Hammath Tiberias Synagogue, 286–337 C.E. (Manar al-Athar)

Sol or God the Creator?

View of the western wall of a model of the Dura-Europos Synagogue with view of its narrative wall paintings and Torah shrine as it may have appeared between 244 and 256 C.E. The paintings are based on photographs taken prior to 1967. The model was created by Displaycraft in 1972 (collection of Yeshiva University Museum, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Since its discovery in 1961, the Hammath Tiberias mosaics have drawn significant attention. On the one hand, these images defy the widely held assumption that Judaism is a non-visual tradition, either not producing visual art at all or creating only non-figural images, due to the Second Commandment prohibition against the creation of graven images. The Hammath Tiberias mosaics, along with the discovery of several other ancient synagogue floors filled with figural imagery and the extensive figural paintings of the contemporaneous Dura-Europos synagogue in Syria, emphatically dispel this notion.

During the late Roman and early Byzantine periods in which the synagogue mosaics were produced, through to the present day, Jewish communities have interpreted the Second Commandment liberally, not considering figural images to be idolatrous. Nevertheless, the question remains, how did the Jewish community of Hammath Tiberias reconcile their Jewish faith with the personification of the sun god Sol at the center of their most sacred space?

Mosaic with Sol, Luna, Aion, and the four seasons, House of Silenus, Thysdrus (Tunisia), late 3rd–early 4th century C.E. (Ariel Fein, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

No singular interpretation can fully explain the figure of Sol in Hammath Tiberias and other Galilean synagogues; however, the range of possibilities reflect the complexity of Jewish communal life in late antiquity. Some interpretations understand Sol at Hammath Tiberias as nothing more than an image of the sun. Although Sol is a god, Sol differs from almost all other Roman gods; after all, the sun is a natural, visible phenomenon. So, while some images represented Sol as a god in a traditional sense, including in cult statues and depictions of mythological scenes, Sol also appeared as a representation of the sun and the heavens. For example, a mosaic floor from the house of Silenus in Thysdrus (modern-day Tunisia), includes busts of Sol, Luna (personification of the moon), and Aion, a Roman deity associated with cyclical time, alongside personifications of the four seasons. Shown together, they evoke the heavens and the annual passage of time. According to this interpretation, the mosaic image of Sol at Hammath Tiberias, along with the surrounding moon and stars, and the figures of the zodiac, may depict the Jewish heavens or a calendar, taking part in a complex visualization of the Jewish cycle of sacred time.

On the other hand, it is possible that the representation of Sol may in fact reflect the actual worship of the cult of the Sun God in Jewish circles in the 3rd century. By this time, sun worship, focusing on the Roman deity Sol, was embedded in Roman religious practices. At the same time as the cult of the sun took center stage amongst the Roman polytheistic population, Jewish laws composed and compiled by the rabbis reflected a real fear that Jews would worship the sun and moon. A Jewish magic book from the late 3rd or early 4th century, for example, includes a prayer in honor of Helios (the Greek name for Sol). Perhaps the synagogue floor mosaics represent an aspect of popular Jewish worship, practiced by Greek-speaking Jews who were familiar with local cult practices.

Temple and Zodiac panel with Sol, Hammath Tiberias, 286–337 C.E. (Manar al-Athar)

More likely, rather than evidence of Jewish sun worship, the synagogue’s mosaics (both the figure of Sol as well as the imagery of the zodiac), suggest the level of acculturation of the Jewish community to their Roman neighbors. Having lived under Roman rule for centuries, Jews were intimately familiar with the institutions of Roman life. They borrowed and adapted the visual formulae used in Roman art and architecture within their own constructions. First and foremost, the patrons of the Hammath Tiberias Synagogue decorated their holy space with mosaics—a ubiquitous medium throughout the Roman Empire, found in bathhouses, marketplaces, temples, churches, and private homes, meant to impress and convey wealth and prestige.

Triumph of Neptune, Roman mosaic from La Chebba, Tunisia, late 2nd century C.E. (Tony Hisgett, CC BY 2.0)

Moreover, in the selection of geometric and figural imagery, the Hammath Tiberias floors drew heavily upon the local Roman and the later Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire’s mosaic repertoires. For example, a comparable image of Sol leading his chariot through the universe can be seen in a mosaic from a 3rd-century Roman villa, as well as representations of other deities ruling from their chariots, such as the god Neptune in a late 2nd-century mosaic from La Chebba (modern-day Tunisia).

In the Hammath Tiberias floors, the representation of the sun god may have been conceived of as a Judaized Sol Invictus—the Jewish god as the single, invincible ruler of the universe. The purple color of the young god’s tunic and his globe are reminiscent of Roman imperial images. Moreover, Jewish sources in late antiquity referred to God’s supremacy by connecting his power with symbols of authority, such as riding a horse or chariot. By adapting this imperial motif of Sol Invictus, the synagogue floor conveyed the God of Israel’s absolute power over the universe—the land and sea from which the chariot emerges—and all of time, captured in the surrounding zodiac.

Visualizing time

For the Jewish community worshiping within the Hammath Tiberias synagogue, the images of the mosaic floor, combined with the synagogue’s furnishings, may have offered a vision of Jewish time—past, present, and a hope for a messianic future. The synagogue’s representation of the ancient Temple in Jerusalem, depicted the Jewish past. During the The First Jewish-Roman War, in which the Jewish population rebelled against the Romans, the Roman army laid siege to the city of Jerusalem, destroying the Temple and leaving the Jewish people without a religious center to bind them together. Over time, new institutions and leaders arose to fill that void. Synagogues offered new spaces where the Jewish community could gather to read the Hebrew Bible, pray, and form a sacred community with their God.

Left: Menorah from a second synagogue in the town of Hammath Tiberias, known as Hammath Tiberias A, 5th–6th century C.E., limestone (Israel Museum); right: Torah Ark lintel, Nabratein synagogue, 3rd century C.E. (Davidbena, CC BY 4.0)

The Hammath Tiberias mosaics representing the ancient Temple appeared just before the part of the synagogue where the the Torah shrine was located. Although few Torah shrines have survived intact, a stone lintel of a Torah shrine from a 6th-century synagogue in the Jewish village of Neburaya in the upper Galilee, gives us a sense of what the original shrine in the Hammath Tiberias Synagogue would have looked like. Its arched form closely resembles Hammath Tiberias’s mosaic image of the ancient Ark of the Covenant. Moreover, just as in the mosaic floor, Hammath Tiberias’s Torah shrine likely would have been flanked by two seven-branched stone menorahs, like the menorah uncovered at a 5th- or 6th-century synagogue in the same town. Framed by stone candelabras, the near mirror image between the Hammath Tiberias mosaic floor and its furnishings would have reflected an attempt to associate the synagogue with the ancient Temple, as both descending from and replacing the now-obsolete Temple rituals. The mosaic may have also symbolically signaled a longing for the future rebuilding of the Temple and the restoration of its cult practices. According to Jewish tradition, with the coming of a messiah, the temple will be rebuilt and its rituals restored. Thus, the Temple panel and the synagogue’s bema visualized past, present, and future Jewish worship.

This concept of time is anchored in the imagery at the center of the synagogue—the four seasons, the zodiac, and the sun (Sol), moon, and stars. Together they presented a Jewish vision of daily, monthly, and annual cycles of time, offering a multilayered affirmation of God’s covenant with the Jewish people throughout history. Such themes would have been especially appropriate for the Jewish community living under Roman rule. It would have emphasized the legitimacy of Jewish monotheistic tradition in the face of the polytheistic Roman cults.

By the 5th century, this imagery became even more relevant, as the Jewish community faced a rising threat—Christianity. These two monotheistic religions had rival claims to a covenant with God. While both sought their foundations in the text of the Hebrew Bible, Christianity conceived of Judaism as a tradition it had superseded. For Christian readers, Hebrew scriptures recount the history and prophecies of God’s original chosen people and foreshadow God’s new covenant with the Christian people.

Mosaic with Helios (Sol) and Selene (goddess of the moon) and the labors of the month, Monastery of Lady Mary, Scythopolis, 6th century, watercolor by A. Bentwich (Penn Museum)

Christ as Sol Invictus, 3rd–4th century C.E., Tomb of the Julii (Mausoleum M), Vatican Necropolis (Tablar)

With their competing universal claims, the Jewish and Christian communities looked to the same visual language to express their legitimacy. Just as at Hammath Tiberias, Christian patrons transformed Jesus into the solar emperor of the universe, Sol Invictus. In a mausoleum beneath St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, for example, we see a possible Christianized Sol Invictus, a figure bearing a cross-shaped nimbus riding on a chariot with a sunburst halo. Similarly, the 6th-century monastery of Scythopolis (Beth Shean) in the Galilee also includes a floor mosaic of the zodiac with Sol and a personification of the moon at its center. As the new Christian religion developed, gaining imperial support and followers, the Jewish community needed to define and defend their own legitimacy as inheritors of God’s promise to the Jewish people. By visually staking a claim to the Jerusalem Temple and God’s covenant, and using Sol Invictus as a symbol of the Jewish God’s infinite powers, they declared that the messiah described in Christian doctrine had not yet come, emphasizing that the Jews, and not the Christians, are the chosen people of the Hebrew Bible.