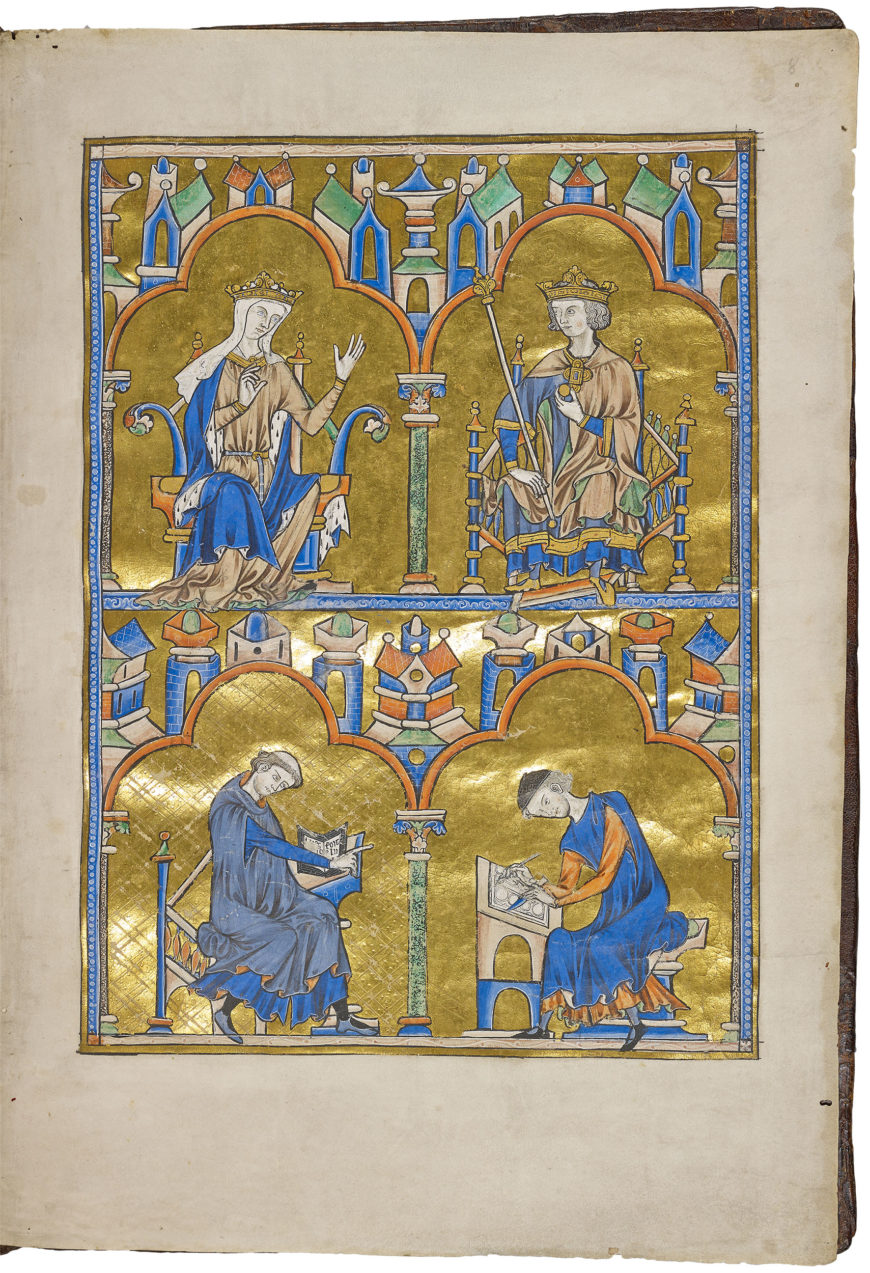

Middle left (detail), Scenes from the Apocalypse, Paris-Oxford-London Bible moralisée, France, c. 1225–45 (The British Library, Harley MS 1527 fol. 140v)

One book, thousands of illustrations

Biblical text and commentary

Bible moralisée contain two texts: the biblical text and the commentary text, which is sometimes called a gloss. These commentary texts interpreted the biblical text for the thirteenth century reader. Commentary authors often created comparisons between people and events in the biblical world and people and events in the medieval world. In the case of the Bible moralisée, the commentary often draws parallels between the bad guys of the biblical text and those who were perceived as bad guys in the thirteenth century. In France, as in most of western Europe at this time, Jews and corrupt priests were the bad guys and there are anti-semitic themes throughout the commentary and illustrations.

The format of Bible moralisée manuscripts is unusual, as the artist had to create a coherent arrangement for the biblical text, its accompanying commentary text, and an illustration for each. On each page of this manuscript there are eight circles, called roundels, that illustrate biblical scenes and commentary scenes. There are short snippets of text, either from the bible or commentary, that accompany each scene.

And the angel thrust in his sharp sickle into the earth, and gathered the vineyard of the earth, and cast it into the great press of the wrath of God (Douay-Rheims translation)

Upper left (detail), Scenes from the Apocalypse, Paris-Oxford-London Bible moralisée, France, c. 1225–45 (The British Library, Harley MS 1527 fol. 140v)

The illustration is a visual interpretation of this text, with some extra details added. A figure on the right harvests grapes from the vines on the right and Christ, with his cruciform (cross-shaped) halo, pours the grapes from the basket on his back into the winepress. God and his angels bless the scene from above.

Left: Commentary (detail), Scenes from the Apocalypse, Paris-Oxford-London Bible moralisée, France, c. 1225–45 (The British Library, Harley MS 1527 fol. 140v); right: Middle left (detail), Scenes from the Apocalypse, Paris-Oxford-London Bible moralisée, France, c. 1225–45 (The British Library, Harley MS 1527 fol. 140v)

The commentary begins with the red letter “P” below and talks about how the great winepress signifies hell. Note that in the accompanying illustration, there are demons herding the damned into a hellmouth—literally the jaws of hell. Among the damned is a corrupt bishop, identified by his special hat, the mitre. There is also a corrupt king in hell.

This arrangement gives the biblical text three interpretations: a visual interpretation, a commentary interpretation, and a visual commentary interpretation. Each interpretation builds on the other. The illustrations are more than simple representations of the text, they are contemporary interpretations of it. The commentary text does not mention bishops or kings, but the illustrator adds those.

The reader then moves on to the right, to the next pairing of images and text.

Upper right (detail), Scenes from the Apocalypse, Paris-Oxford-London Bible moralisée, France, c. 1225–45 (The British Library, Harley MS 1527 fol. 140v)