St. Sernin, Toulouse, France, c. 1080-1120 with later additions (photo: Holly Hayes, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The political center of Toulouse, France today is Place du Capitole, an open city square to the east of a beautiful eighteenth-century neoclassical building. Two major north-south roads traverse the western side of this square, and the names of these two thoroughfares have much to say about the history of the city. The street on the southern end of the square — Rue de Sainte-Rome — is named after a long since destroyed thirteenth-century Dominican church, Sainte-Romain. The street that proceeds northwards from the northwest corner of Place du Capitole — Rue du Taur — whispers the smallest of hints as to the most important church in the city, Saint-Sernin.

Place du Capitole, Toulouse, France (photo: Benh LIEU SONG, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A martyred saint

This imposing Romanesque basilica was constructed in honor of St. Sernin (Saturninus in Latin), the first bishop of Toulouse. He was born in the early third century in Greece, and was one of seven bishops that Pope Fabian sent to different parts of Gaul to actively preach the Christian gospels to the pagans who lived in those areas. Many stories that pertain to the early Christian martyrs are fantastical, and we should take Sernin’s own narrative with the proverbial grain of salt.

Notre Dame du Taur, Toulouse, France, 14th century (photo: Didier Descouens, CC BY-SA 4.0)

According to legend, when Sernin entered the city of Toulouse, all of the pagan idols — which hitherto had regularly spoken to their priests — suddenly and disturbingly fell into silence. One day in 257, a great group had gathered around an altar, and a man pointed to Sernin as the cause of this divine silence, exclaiming, “There is the one who preaches everywhere that our temples must be torn down, and who dares to call our gods devils! It is his presence that imposes silence on our oracles!” Sernin was then chained to a nearby bull and drug through the city until his body was broken and skull crushed. His corpse was eventually deposited on a street that since those times has been called the Rue du Taur, the Road of the Bull. A church appropriately called Notre Dame du Taur commemorates the spot where the bull finally deposited the lifeless body. About 300 meters further north is Saint-Sernin, the basilica where the martyred saint’s bodily remains are purported to reside.

A pilgrimage church

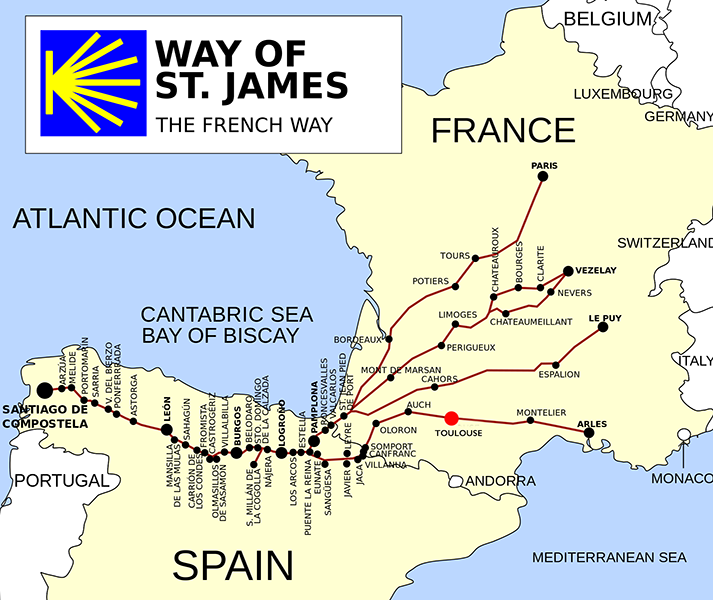

Begun sometime around 1080 (approximately 825 years after the saint’s death), Saint-Sernin was formally consecrated as a church about a century later. The opening centuries of the second millennium were a time of great religious pilgrimages, and one of the most important pilgrimage sites for the Catholic faithful — then as now — is the cathedral of St. James in Santiago de Compostela, a city in northern Spain. For the pilgrims commencing their journey in Italy, the path they travelled took them through the southern part of France, and one of the major stopping points on this section of the Santiago Trail — the Way of St. James — was the city of Toulouse and the basilica of Saint-Sernin, the church that held the relics of one of the most famous martyred saints of the area.

The Way of St. James — routes from France (image: Vivaelcelta, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Saint-Sernin is an excellent example of a Romanesque pilgrimage church, a building that needed to accomplish two interrelated ends. First, the structure needed to provide a suitably inspiring shrine for the holy relics of the saint it was built to commemorate. Second, it needed to be large enough to accommodate the thousands of pilgrims who would arrive each day to pray before and venerate those relics. Fulfilling these two goals, Saint-Sernin is one of the best-preserved and perhaps the largest Romanesque churches in the world. Even almost 950 years after its construction was begun, it remains a religious structure that awes and inspires the pilgrims who still visit.

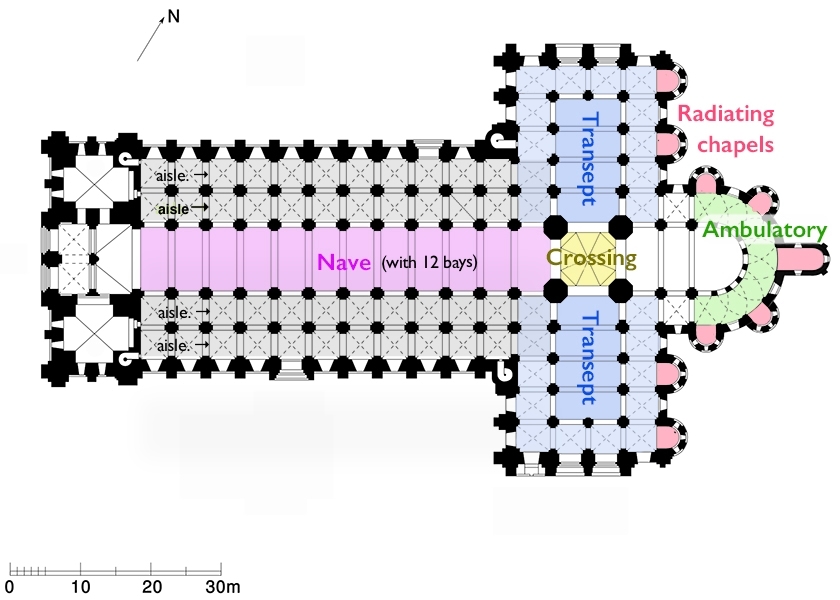

The Romanesque style is so called because the medieval architects who designed these buildings used a fundamentally Roman architectural language. Romanesque churches are notable for their thick walls with relatively few windows, Roman arches, barrel vaults, and the use of massive vaulting. In contract to the Gothic buildings that would become fashionable a couple of centuries later, Romanesque churches appear heavy and comparatively dark. Saint-Sernin is also an excellent example of a church with a Latin cross plan. A long central east-west nave is intersected by a shorter north-south transept, a shape that mimics the most recognizable symbol of the Christian faith.

One of the best ways to fully appreciate a medieval church is to stroll around its exterior. Indeed, during this circumnavigation, one is not only transported back in time, but also through time. It often took centuries to construct churches of the size and scale of Saint-Sernin. By walking around the exterior of these churches an observant visitor can clearly see shifting architectural styles and changing sculptural aesthetics. Although construction was begun on Saint-Sernin by about 1080, slight changes in the proportion of brick and stone used during the course of its construction suggest the church went through a number of different building campaigns from its genesis until its ultimate conclusion, perhaps as many as four. Romanesque (and Gothic) churches are often a negotiation between what was dreamed and what came to pass; the final church often looks different from its original architectural plan.

Basilica of Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, France, c. 1080-1120 with later additions (photo: Guillermo Fdez, CC BY-NC 2.0)

This is evident when looking at the west façade of the church (in medieval churches, this is commonly referred to as the westwork). Most churches during the late medieval period were constructed with a tower on both the north and south ends of the westwork, and the extensive and massive buttressing on the corners of the west façade of the structure strongly indicate that such towers were part of the original plan of the church. In the absence of these vertical towers, the front of the church is instead dominated by its large central circular window, set into a shallow pointed arch recession. Underneath this window are five small Roman (round) arches that harmoniously frame the two large Roman arch entranceways. This central part of the façade — from the large entrances to the circular window — is framed by the vertical buttresses on the left and right sides.

Basilica of Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, France, bell tower c. 1270-1470 (photo: Guimsou, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Walking from the front of the church along one of the sides brings into focus the large bell tower over the crossing. The octagonal tower is made of five layered tiers that are capped by a spire. The first three tiers feature Roman arches and were likely begun in the twelfth century. The much later uppermost tiers date from about 1270 — nearly two centuries after construction the church first began — and feature Gothic pointed arches. The spire at the top was finally completed around 1470 and measures 213 feet (65 m) in height. The bell tower alone is a visual lesson in the shifting architectural styles in fashion over the four centuries of a church’s construction.

Basilica of Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, France, apse and radiating chapels, c. 1080-1120 with later additions (photo: Pierre-Selim, CC BY 2.0)

If the bell tower and its spire are the elements of the church that are most visible around the city of Toulouse, it is the architectural elements on the eastern side of the church — the apse end — that made Saint-Sernin famous. It was common during the medieval era for the apse of the church to have small chapels for the placement of holy relics where pilgrims could come to visit and venerate them. But in Saint-Sernin, the entire eastern end of the church — from the north transept, around the apse, and concluding on the southern transept — is filled with nine radiating chapels. Even from an exterior view, it is clear that one of the primary roles of this structure was to house relics for pilgrims to visit.

Basilica of Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, France, view of the nave toward the apse, c. 1080-1120 (photo: PierreSelim, CC BY 3.0)

Chapels, sculptures, and the tomb of a saint

The plan of the interior of the church reinforces this function. The large barrel-vaulted central nave is flanked on each side by double side aisles. When standing in the nave the faithful look towards the same high altar that Pope Urban II consecrated on 24 May 1096.

The nave is 69 feet in height and is twelve bays in length from the entrance (the narthex) to the crossing. Each bay is twice as wide as it is long. Harmoniously, these same proportions are mirrored by each of the double side aisles that flank the nave, thus creating a profound architectural unity. This unity is likewise reflected by the arches that separate the nave from the innermost side aisle and the arches in the triforium that allow light to flood into the nave.

Elevation, St. Sernin, Toulouse, c. 1080-1120 (photo: kristobalite, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

If the primary function of the nave was for the celebration of the Catholic mass, then the double side aisles allowed the throngs of pilgrims who arrived daily to visit the nine radiating chapels without interrupting any religious service in process. A pilgrim might enter the church, turn to their left, and then proceed down a side aisle and move along the transept. From there, they could worship and venerate at any of the nine radiating chapels and see the works of art located in the ambulatory. Of particular note is a large-scale relief of Christ in Majesty that dates from c. 1096. Jesus sits in a shallow mandorla; he raises his right hand in a gesture of blessing while his left hand holds a gospel with the words Pax Vobis — “Peace to You” in Latin — inscribed on the pages. Symbols of the four gospel writers look towards Jesus from the four corners.

Basilica of Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, France, Christ in Majesty relief, c. 1096 (photo: Frédéric Neupont, CC BY 2.0)

The main attraction of the basilica, however, is the tomb of Saint Saturnin that is located on the inner part of the ambulatory. To reach this space, a pilgrim would enter through a doorway where the lintel was carved with the head of Christ flanked by two scallop shells, visual symbols for the pilgrimage trail to Santiago de Compostela. Immediately underneath this lintel — on the iron gate that serves as a barrier — are the words Non Est in Toto Sanctior Orbe Locus; “There is no holier place on earth.”

Saint-Sernin also featured upper and lower crypts that could be visited while in the ambulatory, which contained various shrines and reliquaries. Concluding their visit, the traveling pilgrims would then walk along the side aisle opposite the one they had previously used and then exit the church.

Basilica of Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, France, entrance to the tomb of Saint Saturnin, c. 1080-1120 (photo: Dr. Bryan Zygmont)

Looking to St. James

While the Basilica of Saint-Sernin may have served as a kind of stopping point for pilgrims on the Way of St. James, it became a kind of pilgrimage destination in its own right in the decades after its construction. Indeed, it is a near contemporary with the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela (c. 1078), and there is some disagreement about which church is older, as some architectural historians date the groundbreaking for Saint-Sernin to 1077. Regardless of which is older, there is one important note that is generally well accepted: there is clear relationship between the two buildings. Both are Latin cross in plan, and both feature nine radiating chapels on the eastern side of the church. In arriving in Santiago de Compostela, those pilgrims who had traveled together along the southern path of the Way of St. James and had previously visited Saint-Sernin would have encountered a church that familiarly whispered to them.