Apse mosaic depicting the Virgin and Child, dedicated 867, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

For many of us, the term “mosaics” evokes the soaring golden walls and ceilings of the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire. But from approximately the twelfth to the fourteenth century, the Byzantines also began creating mosaics that were portable and sometimes small enough to fit in the palm of the hand.

Historians often speak of the Late Byzantine period (1261–1453) as an age of “decline.” During this time, the Byzantine Empire—which was a continuation of the ancient Roman Empire—shrank until it was finally conquered by the Ottomans in 1453. But Byzantine miniature mosaics, which emerged as a new art form in the twilight of the Empire, show that even as Byzantium’s imperial prospects faltered, artistic creativity and patronage continued to flourish.

Floor mosaics, c. 139 C.E., Baths of Neptune, Ostia, Italy (photo: Nicholas Hartmann, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Mosaics

A mosaic is an artwork made by combining small cubes (tesserae) of stone, glass, ceramic, or another material to create a pattern or image. The ancient Romans often used mosaics to decorate floors, as seen at the Baths of Neptune in Ostia. In some cases, ancient Roman mosaics utilized small, colored tesserae that enabled them to appear almost like paintings.

Later, the Byzantines frequently used mosaics to decorate the walls and ceilings of churches. Mosaics were the costliest form of monumental decoration in Byzantium, and were generally favored by imperial and other elite donors, as seen, for example, in the church of San Vitale in Ravenna and in Hagia Sophia, the cathedral in the Byzantine capital of Constantinople (modern Istanbul).

Mosaic of Christ (center) with emperor Constantine IX (left) and empress Zoe (right), 1042–1055, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Miniature mosaics

From around the twelfth century to the fourteenth century, the Byzantines also began creating portable mosaic icons by setting small tesserae into wax or resin on wood panels, which were often enclosed in silver-gilt frames. These objects are sometimes referred to as “miniature mosaics” or “micro-mosaics.” While the Byzantines had long used mosaics for large scale images in buildings, this new use of mosaics to create smaller, portable images was innovative.

Since monumental mosaics were generally viewed from afar, individual tesserae tended to blend together in the vision of the beholder. But since miniature mosaics could be viewed up close, artists began employing tiny tesserae—often as small as 0.5–1 mm, or even smaller—to create a blended rather than a “pixilated” appearance. Such objects must have demanded considerable time and skill to create.

There is little evidence to indicate where or why miniature mosaic icons began to be produced when they did. Some scholars theorize that miniature mosaics may have initially emerged as a preparatory step in the production of monumental mosaics, which enabled artists to plan ahead what they would put on walls or ceilings. Because of the cost and skill that must have been required to produce them, miniature mosaic icons were likely created for imperial and other elite patrons by artists who produced luxury objects in Constantinople. Some fifty miniature mosaic icons survive—most of them from the Late Byzantine period—although many are badly damaged. Byzantine inventories suggest that more once existed, which have not survived.

Mosaic icon of the Virgin Glykophilousa, late 13th century, Triglia in Bithynia, near Constantinople, 107 x 73.5 cm (photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC0)

Larger mosaic icons, such as the thirteenth-century icon of the Virgin Glykophilousa in Athens, sometimes measured several feet tall. Their size suggests they may have been publicly displayed and venerated in churches. Some may have been installed on the templon barrier that divided the altar area from the rest of the church. Other mosaic icons, such as the early fourteenth-century icon of the Virgin Eleousa in New York, were small enough to be held in the palm of one hand. They would have been too small for public display and were likely used in private devotion.

Portable icon with the Virgin Eleousa, early 1300s, probably made in Constantinople (photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0)

An Icon of Christ’s Transfiguration

A mosaic icon of Christ’s Transfiguration in the collection of the Louvre Museum in Paris offers an early example of the miniature mosaic technique, dating from c. 1200. Its miniature tesserae—made from gilded bronze, marble, lapis lazuli, and glass—measure between 0.5 mm and 1 mm on a side (about the diameter of a pencil lead). Its owner(s) undoubtedly treasured this icon not only for its beauty and religious significance, but also as an object of great luxury. Based on its size, this icon may have been displayed in a church or used for private devotion.

Icon of the Transfiguration, beginning of the 13th century, Constantinople, mosaic, 52 x 36 cm (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Transfiguration Apse mosaic, 6th century, the Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine, Sinai, Egypt (photo: Europa Nostra, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The icon depicts the Transfiguration as described in the New Testament—in Matthew 17:1–13, Mark 9:2–8, and Luke 9:28–36—when Christ reveals his divinity to three of his apostles, Peter, James, and John. Christ and his apostles climb a mountain (identified by tradition as Mount Tabor). Suddenly, Christ is transformed, radiating brilliant, heavenly light. Moses and Elijah, prophets from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians refer to as the Old testament), appear on either side of Christ, and the voice of God from heaven identifies Jesus as his Son. The apostles fall down before Christ in fear. The white tesserae used to create Christ’s garments and the mandorla of light that surrounds him, as well as the reflective, gilded tesserae used for the rays and background, must have helped evoke the divine light for Byzantine viewers. The composition closely corresponds with some of the earliest surviving images of the Transfiguration, such as the sixth-century mosaic in the apse of the basilica of the Monastery of Saint Catherine at Sinai, Egypt.

Portable Icon with the Virgin Eleousa, early 1300s, probably made in Constantinople, miniature mosaic set in wax on wood panel, with gold, multicolored stones, and gilded copper, 11.2 x 8.6 x 1.3 cm (photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0)

An Icon of the Virgin Eleousa

Virgin of Vladimir, 12th century with later repainting, tempera on wood, (photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC0)

Another miniature mosaic icon (mentioned above) depicts the Virgin and Child rather than a narrative scene and is part of the collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Created in the early 1300s, roughly a century after the Louvre’s Transfiguration icon, the Met’s miniature mosaic shows the Virgin Eleousa (“compassionate”), who tenderly holds the Christ child to her cheek. The Virgin Eleousa was one of many compositions of the Virgin and Child in Byzantium; its best-known example is probably the Virgin of Vladimir, which was transferred from Byzantium to Russia in the twelfth century, where it became well-known and widely imitated.

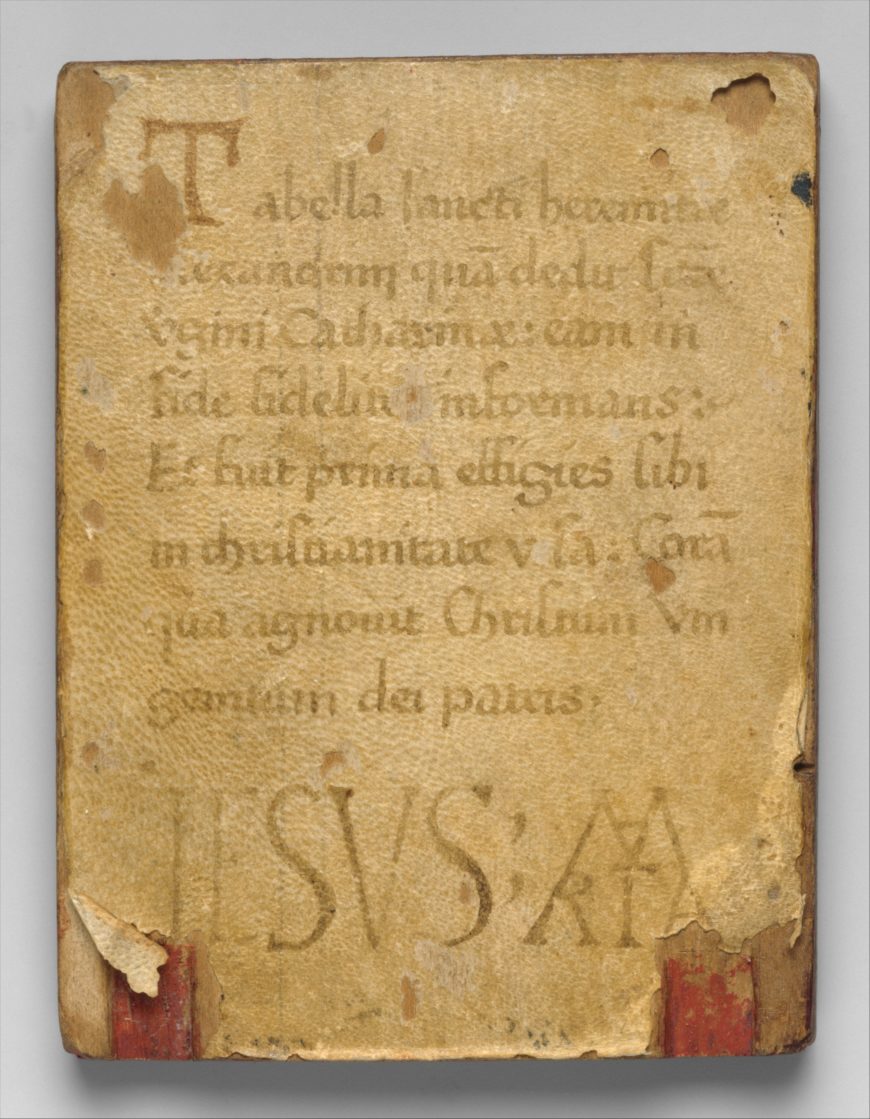

The miniature mosaic icon of the Virgin and Child at the Metropolitan is smaller than the Louvre’s Transfiguration, measuring 11.2 x 8.6 cm, and likely functioned as a private devotional object. A fifteenth-century Latin inscription on the icon’s back testifies to its preservation in western Europe following the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453.

Latin inscription, portable icon with the Virgin Eleousa (reverse), early 1300s, probably made in Constantinople (photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0)

An Icon of the Forty Martyrs of Sebasteia

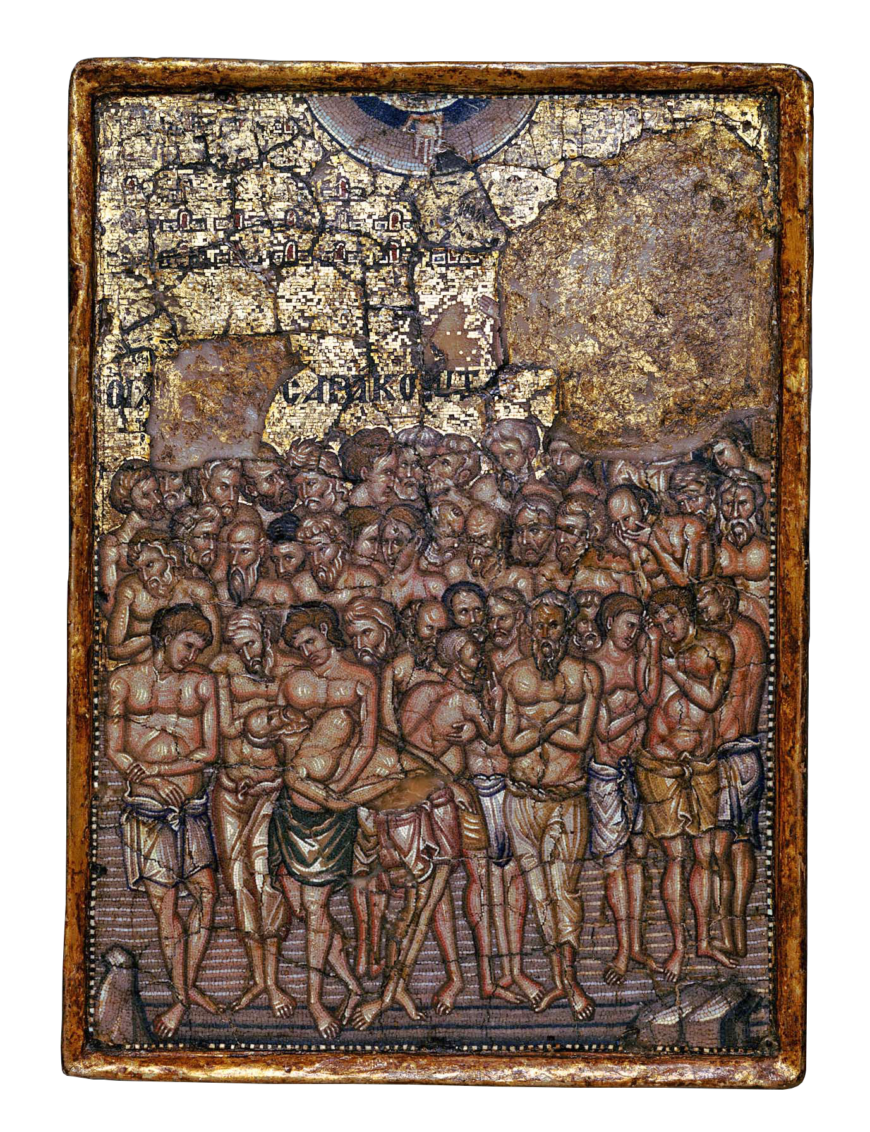

Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C. preserves another fine example of Byzantine miniature mosaics, this time picturing an account of Christian martyrdom: the Forty Martyrs of Sebasteia. The icon dates to the late thirteenth century, combines gold and multicolored stone tesserae set in wax on a wood panel, and has been somewhat damaged. The icon utilizes tiny tesserae measuring less than 0.5 mm, which must have made the production of this icon long and difficult, but which gives the image an almost painterly appearance.

Miniature mosaic icon with the Forty Martyrs of Sebasteia, 13th century, Byzantine, stone and glass on wax and wood, 22 x 16 cm (photo © Dumbarton Oaks)

The image recounts the tale of forty Roman soldiers sentenced to die for their Christian faith by exposure in a frozen lake in Lesser Armenia around 320 C.E. The artist has taken no shortcuts, rendering the figures in individual poses that convey their suffering. One man in the foreground collapses. Another, in the upper right, holds his hands to his face in distress. The soldiers’ suffering is vindicated as the hand of God bestows crowns of martyrdom on the soldiers from a heavenly dome in the top of the mosaic.

Miniature mosaic icon with the Forty Martyrs of Sebasteia, 13th century, Byzantine, stone and glass on wax and wood, 22 x 16 cm (photo © Dumbarton Oaks)

Such miniature mosaic icons illustrate how the arts flourished in the final centuries of the Byzantine Empire. Although the medium of mosaics had been used to decorate buildings since ancient times, artists from the twelfth-century onward reimagined the medium to create small, portable icons that were nothing short of innovative.

Additional resources

Smarthistory’s free Guide to Byzantine Art e-book

Edmund C. Ryder, “Micromosaic Icons of the Late Byzantine Period” (PhD diss., New York University, 2007)