Model of the western wall of a Dura-Europos Synagogue with view of its narrative wall paintings and Torah shrine as it may have appeared between 244 and 256 C.E. The paintings are based on photographs taken prior to 1967. The model was created by Displaycraft in 1972 (collection of Yeshiva University Museum)

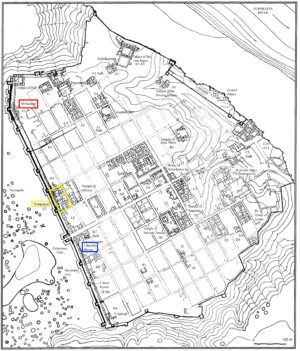

The location of the synagogue in the L7 block is indicated in yellow. Site plan showing orthogonal (grid-planned) city blocks filling c. 52 hectares (128.5 acres) within the city walls and defended by steep cliffs on three sides. Plan by A. H. Detweiler, modified by J. Baird. Original used by kind permission of Yale University Art Gallery

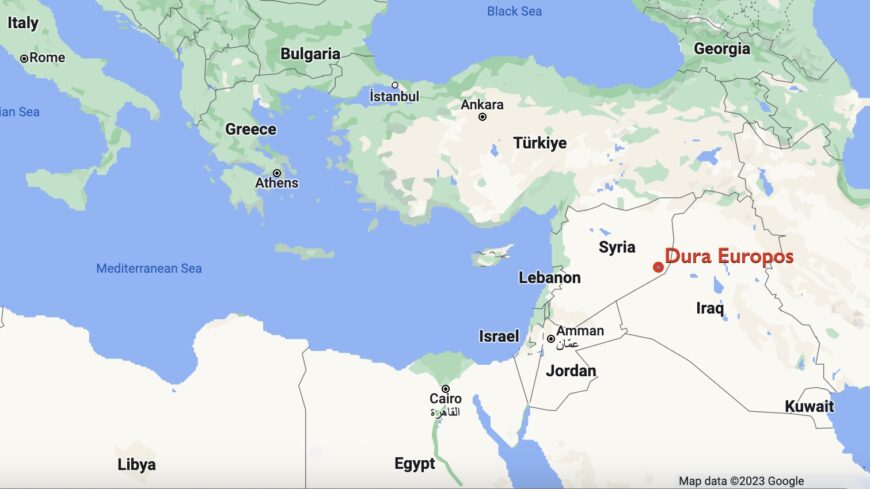

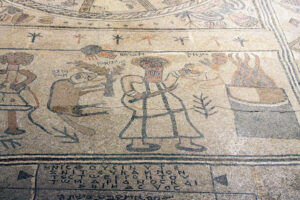

Discovery of a 3rd-century C.E. synagogue at the ancient site now known as Dura-Europos (in modern Syria) in 1932/1933 shocked the scholarly world. To that point, many had assumed that Jews would never create such an elaborately painted structure for worship—in antiquity or otherwise—because of traditional interpretations about prohibitions against making figural images in the second biblical commandment.

Yet, extensive representations of biblical figures and scenes on the walls of the synagogue’s assembly hall dispel this notion. Moreover, the presence of Hebrew and Aramaic writing on the walls and the ceiling, paired with an additional Persian inscription on the murals that explicitly describes the space as dedicated to the “God of Gods of the Jews,” collectively confirmed its use by Jewish worshippers. [1] Combined, these elements of the synagogue offer rare documentation of Jewish life and devotional space in a 3rd-century frontier town, situated within a multilingual and multicultural society.

The Dura Synagogue and the circumstances of its preservation

Decades before the construction of the synagogue, sequences of conquest, destruction, and rebuilding had already shaped Dura into a politically, culturally, and demographically complex town. Roman soldiers fortified Dura in the mid-250s C.E., inadvertently protecting the synagogue (their efforts included back-filling buildings along the defense walls of the town, including the synagogue, to bolster their resistance to demolition by the enemy’s battering rams).

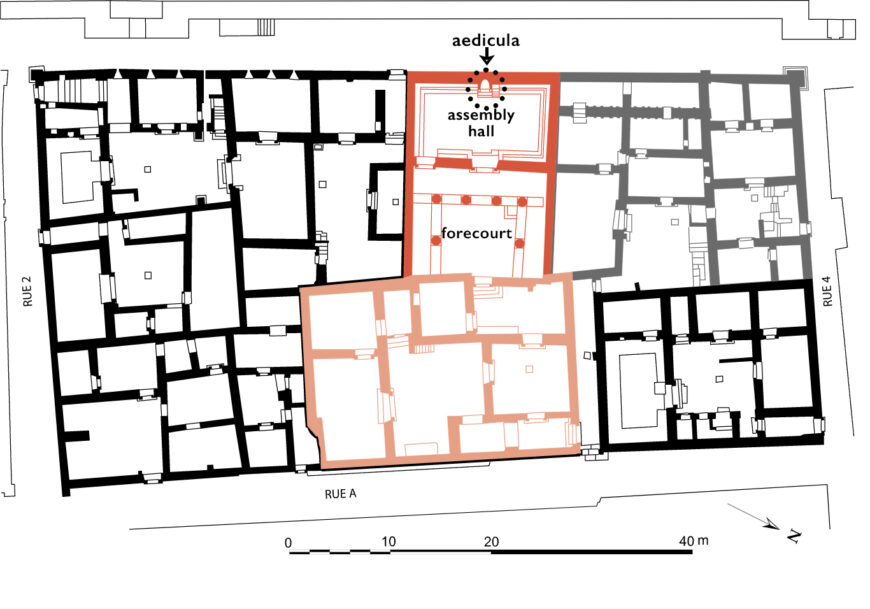

Plan of the L7 block of Dura-Europos with the synagogue (last state) in red; in orange, the entrance and outbuildings (plan after N. C. Andrews (1941) taken up in Hachlili, Ancient Jewish Art and Archeology in the Diaspora, 1998, 41 after Pearson in Hopkins e. a. 1936; plan: Marysas, CC BY-SA 3.0)

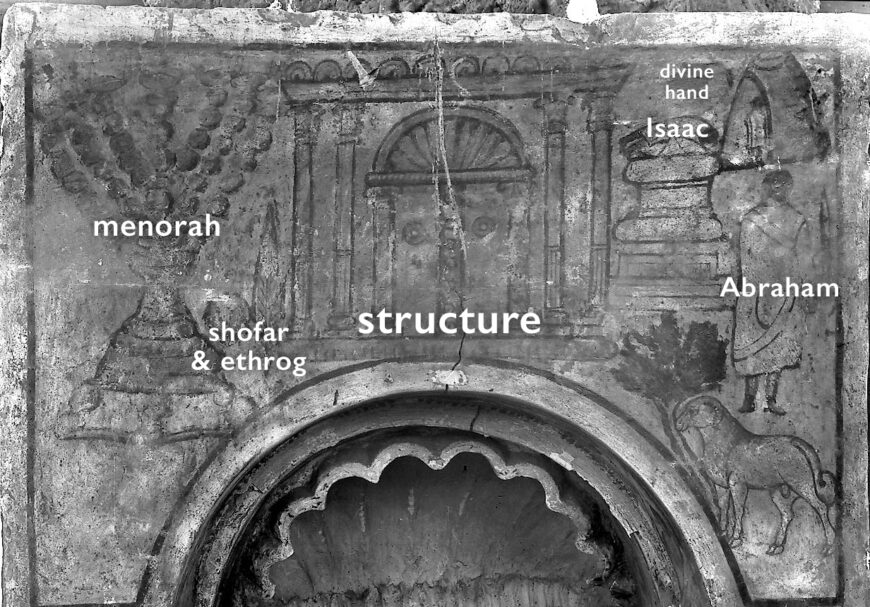

Aedicula from the synagogue, 3rd century C.E., Dura-Europos, Syria. Photographed 1932–33 (Yale University Art Gallery)

Phasing and architecture

Yale University’s excavations in the 1930s revealed that the original synagogue building was probably constructed in the late 2nd century or early 3rd century C.E. While much remains unknown about this earlier structure, its foundations are partly documented and indirectly preserved.

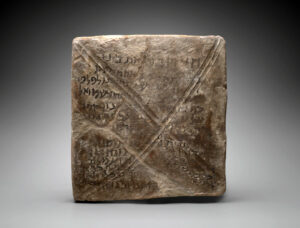

The final phase of the synagogue, which was completed in the 240s, is its best understood. The synagogue was primarily composed of an assembly hall and a forecourt (with entry through the adjacent building). The assembly hall may have accommodated up to 120 people. Opposite the entryway, a sculpted aedicula occupied a central position along the western wall of the assembly hall, accessed by several steps from the floor. The Torah (a scroll containing the first five books of the Hebrew Bible) might have been stored and read possibly in or around the aedicula on this wall.

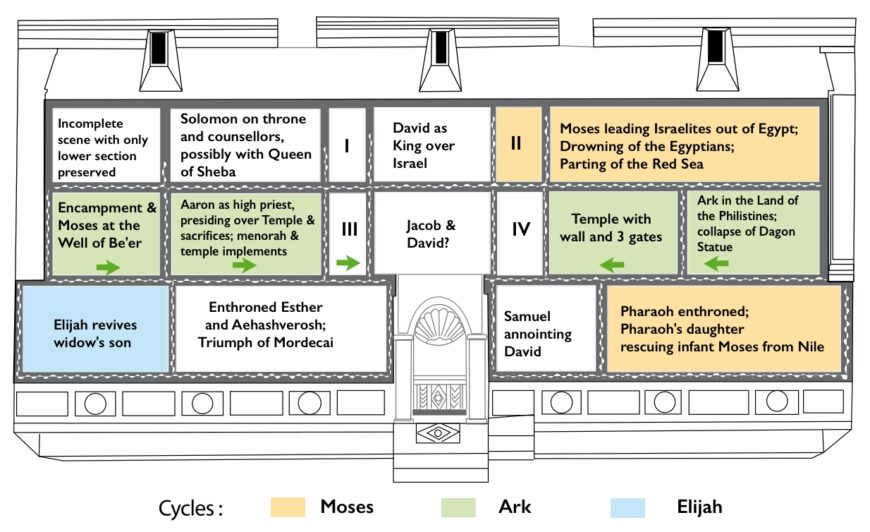

Scenes of the painting west wall frescoes in Dura Europos synagogue (diagram: Marsyas, CC BY-SA 3.0A, ater Weitzmann and Kessler 1990)

Wall paintings

The extensive decorative program on the walls of the final phase of the synagogue included roughly 70 panels depicting stories from the Hebrew Bible. The murals were originally applied to dry, rather than wet plaster (using al secco techniques). [2]

South wall, dado panels 4–6, synagogue, 3rd century C.E., Dura-Europos, Syria (Yale University Archive)

Shrine to Mithras (Mithraeum), c. 240 C.E., painted plaster, 162.5 x 206.4 cm (Yale University Gallery of Art)

Scenes on the walls were presented, out of chronological sequence, in three registers; black rectangular borders divided each panel from others. The lowest decorative band (dado) was distinctive; its colors and decorative program, representing exotic animals and women’s faces or masks in the middle of a black background, separated the biblical panels—both spatially and stylistically—from the floor below.

Similar artisans might have painted the walls of several buildings in Dura, including the synagogue, Christian building, and mithraeum. Nonetheless (and for multiple reasons) the Dura synagogue is exceptional, both locally and regionally; it boasts the most well-preserved decorative program of any Durene building and it contains the only fully decorated walls to survive from any known ancient synagogue.

Painting at the top of the aedicula from the west wall of the synagogue, 3rd century C.E., Dura-Europos, Syria (Yale University Archive)

The west wall

Remaining portions of the west wall, which faced the hall entrances, remain among the best preserved. The aedicula was elaborately and brightly painted. We see a large yellow menorah (a candelabrum with seven branches topped with individual oil lamps), beside which other implements associated with the Temple in Jerusalem also clustered, including a shofar (ram’s horn used as a ritual wind instrument) and ethrog (citron fruit, used by Jews during the festival of Sukkot).

Detail with the hand of God, Beit Alpha synagogue, 6th century, C.E., Israel (Sean Leatherbury/Manar al-Athar)

In the center is an indeterminate architectural structure—perhaps the Holy of Holies from the temple or the Temple itself. On the other side appears an aqeda scene that represents the sacrifice of Isaac. A tiny Isaac appears already on the top of the altar, awaiting his (averted) sacrifice and Abraham appears from behind, and a descending divine hand or the hand of an angel appears to intervene directly from above.

Scholars have offered many theories to explain why these images appear together and in this precise location. Scenes which render cultic implements from the Temple (such as the menorah, shofar, and, ethrog), images of architectural structures, and aqeda scenes appear frequently in mosaic floors of synagogues of Roman Palestine from the fourth and fifth centuries C.E., often closest to where the Torah was likely stored and read. Some scholars have argued that this iconographic and spatial pairing might simultaneously evoke and memorialize the cultic activities of the destroyed Temple in Jerusalem, depict Abraham’s consummate act of piety (his willingness to sacrifice Isaac to demonstrate his obedience to God), and, perhaps, create visual continuity between the destroyed Temple and the liturgical practices conducted within the Dura synagogue centuries later.

Infancy of Moses and the Pharaoh’s daughter, left half, west wall, synagogue, 3rd century C.E., Dura-Europos, Syria (Yale University Archive)

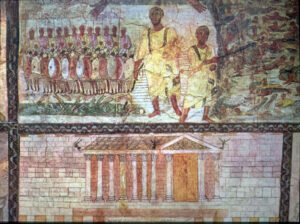

Images on the west wall surrounding the aedicula similarly depict biblical stories about the history and key leaders of ancient Israel. Scenes from Moses’s life are particularly abundant; they include representations of Pharaoh’s daughter rescuing him as an infant from the Nile River and Moses’s leadership of the Israelites miraculously crossing the Red Sea to escape from slavery. Images of the Jerusalem Temple, of Aaron as High Priest, and of the sacrificial activities associated with the Temple cult also recur on the wall.

Synagogue painting, Mordecai and Esther detail, synagogue, 3rd century C.E., Dura-Europos, Syria (Yale University Archive)

Paintings on that wall also depict events of divine intervention, during which Jews were miraculously saved from certain destruction at the hands of their enemies; scenes of the miraculous parting of the Red Sea and the scene depicting Esther enthroned in Persia, collectively function in this way. The positioning of these particular scenes on the same wall that the Torah might have been stored and read appears deliberate.

Moreover, more than serving as mere illustrations of the stories which were recited from the Torah (perhaps with the exception of the Esther story), these representations may play didactic roles, while constituting visual forms of textual interpretation (or midrash). They also serve as spatial and chronological anchors, linking the locations of prayer and recitations of liturgy inside the synagogue to the geography of events within Jews’ historical and religious past.

View of the south wall of the synagogue, 3rd century C.E., Dura-Europos, Syria (Yale University Archive)

The other walls

The other walls are more poorly preserved because they were either partly demolished in antiquity or were badly supported by the fill and thus more susceptible to collapse and destruction. The south wall depicts Elijah and the prophets of Baal; the north wall includes scenes of Bethel and Ezekiel’s vision of dry bones; and images of David and Saul in the wilderness appear on the east. Some of these, as scholars have argued, may depict additional messianic themes.

The Temple with wall and three gates, western wall, right side, from the synagogue, 3rd century C.E., Dura-Europos, Syria (Yale University Archive)

Function of the paintings

These paintings likely served multiple functions for synagogue visitors. They visually conjured and memorialized the greatness of the Jewish God, Jewish heroes and ancestors, and they reminded visitors of a proud lineage that extended back to ancient Israel. Images of the Temple itself, as well as representations of stories in which God saved the Jews from danger, also projected important ideas for their audience, reminding them of God’s power, munificence and protection. Scholars have argued that some images, such as those rendering the vision of dry bones’ in Ezekiel, 37, might suggest God’s promises of future salvation. These images thus simultaneously performed familial, historical, messianic, polemical, and liturgical functions for their ancient viewers. However, the exact relationship between the placement and narrative of many these images remains unclear, because the details of scenes are sometimes abstract and challenging to contextualize.

Replica of ceiling of Dura Europos Synagogue in Damascus Museum, Syria (Yale University Archive). Tiles inside the ceiling were square and 0.42 m and 0.045 m thick.

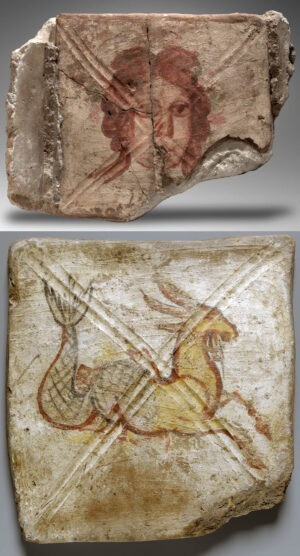

Upper: Tile with Female Face; lower: Tile with Capricorn; both 245 C.E., synagogue, Dura-Europos (Yale University Art Gallery)

Ceiling

Until recently, the ceiling had been a neglected feature of the Dura synagogue. The ceiling was originally framed on joists and supported by wooden beams inset with painted terracotta tiles to suggest a coffered ceiling.

More than 400 square tiles once comprised the ceiling. Most bore figural decoration, including stylized portraits of benignly smiling women, animals, grains, and fruit. They also incorporate fantastical images of composite creatures that may evoke zodiac signs, such as goat-fish, centaurs, and bird-fish; these were joined by at least two representations of the evil or “good” eye, being assailed by weapons and enemies. Some of these images recur in other buildings from Dura, but most do not; this is the only synagogue ceiling to survive from antiquity and scholars are uncertain why these images were selected.

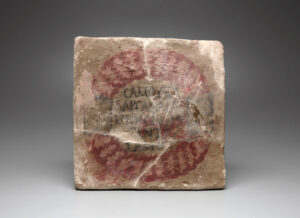

Tile with Greek Inscription in Wreath, 245 C.E., synagogue, Dura-Europos (Yale University Art Gallery)

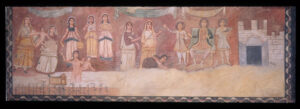

Inscriptions and graffiti

Also painted on some of the ceiling tiles were multiple dedicatory inscriptions, which documented the donations of men to the reconstruction of the final synagogue in 244/5 C.E. Three of the tiles from the Dura ceiling included Greek inscriptions, neatly painted, and surrounded by foliate wreaths, which honored individuals named Abram, Arsaces, Silas, and Salmanes; Samuel son of Yeddayah (“Presbyter of the Jews”); and Samuel son of Saphara (Barsaphara) for their generosity. Two Aramaic tiles described the process of the synagogue’s renovation and were unusually presented in two continuous parts. These inscriptions document the final date of the reconstruction of the synagogue, the synagogue officials who supervised the renovation, records of the hard work undertaken, and honor the participation of unnamed women and children. These also record activities associated with the celebration of the sabbath.

In other synagogues, donor plaques were more commonly placed in areas of synagogues where visitors could view them more easily, such as in floor mosaics and on lower portions of walls. Any explanation for the choice to place donor inscriptions in the ceiling at Dura necessarily remains speculative: these tiles possibly may have been inscribed on the ceiling to bring the donors closer to the higher power of God.

Inscriptions were also found in other areas of the building. An Aramaic dedicatory text was lightly scratched above the aedicula, which attributes the donation of the Torah shrine to a certain “Joseph son of Abba.” The dominance of Aramaic inscriptions inside the synagogue is significant, because, while Aramaic dialects were likely spoken in Dura by Jews and non-Jews alike, Greek is the best documented language in local inscriptions and dedications. Aramaic thus appears to have fulfilled a cultural or ritual importance for Jews who used the synagogue, which is unmatched in other buildings from the town.

A label notes here that “Moses when he went out from Egypt and parted the Sea,” synagogue, 3rd century C.E., Dura-Europos, Syria

Several other types of official inscriptions were also found in the building. Some of these were tituli, or labels, found upon the paintings themselves. Ancient people carefully applied these in paint—in Greek or Aramaic—directly to the paintings. Their work appears to reflect concerns that some of the images were sufficiently ambiguous or difficult for audiences to decipher that they required verbal clarification. Aramaic name labels include those that identify individuals, such as King Solomon (with the Queen of Sheba), Esther, Ahashverosh, and Elijah; a label in Greek identifies the figure of Aaron, the High Priest, who presides over a sacrificial scene. Still panels incorporate fuller captions to help viewers interpret surrounding scenes, such as the label for “Moses when he went out from Egypt and parted the Sea”; or “Samuel, when he anointed David.”

Nearly 70 graffiti were also found inside the synagogue. These include visitor’s unofficial drawings and writings that they applied to the surfaces of the synagogue, during their visits through time. Some record activities of various sorts, such as a carving of an aedicula. Textual graffiti are most abundant. Most textual graffiti are in Aramaic and suggest that writing and carving inside the synagogue was a respectful activity, rather than one of defacement. Examples include the names of individual writers or their families, or several requests that writers should “be remembered,” or “be remembered for good” by future readers and passersby. [3]

Photograph showing dipinti in the Purim panel, synagogue, 3rd century C.E., Dura-Europos, Syria (Yale University Archive)

One last form of writing—usually called dipinti because they are painted, rather than carved as are graffiti— was also found upon certain murals from the synagogue—particularly around the so-called “Purim panel” on the west wall, and around the Elijah and Ezekiel panels on the south and north walls. These are distinctive because they are applied in Middle Persian and Parthian scripts and express visitors’ appreciation for the magnificence of the building and its walls. Most writers identify themselves as scribes, which explains their facility with writing in ink. [4]

Cutting away the painting to remove it from the synagogue, 3rd century C.E., Dura-Europos, Syria (Yale University Archive)

Henry Pearson, one of the excavators at Dura, personally supervised the excision of the synagogue walls and their installment inside a special room constructed for their display inside the Damascus Museum, where they still remain. The precarious military situation of Dura—situated along the Euphrates and the Syrian/Iraqi border in the modern town of Salihiyah—currently precludes visitation. While political factors inhibit direct access to the wall panels of the synagogue in Damascus and to the original archaeological site itself, scholars can continue to study the Dura synagogue and other buildings at the site, through digital projects such as the International Digital Dura-Europos Archive (IDEA) and through the photographic archives and collections of the Yale Art Gallery. The unparalleled richness of elements from the Dura synagogue reminds us of the complex nature of architecture diversities in religious practice, and variabilities in the population in Dura-Europos in the middle of the 3rd century C.E.

Notes:

[1] Aramaic inscriptions on the hall’s coffered ceiling call the space a house (of prayer).

[2] The original colors of the wall paintings are somewhat uncertain. The murals faded rapidly after their excavation and initial exposure. The excavators then painted a shellac on the walls to protect them from further deterioration, but this inadvertently caused the opposite effect: in the decades following synagogue’s discovery the coated surface degraded and darkened considerably. The original black-and-white photographs and negatives captured on site, therefore, offer some of the best documentation of the original appearances of the murals. The colorized images, which are often reproduced, were subsequently painted by Herbert Gute and offer an artistic impression of the ancient colors.

[3] Many such examples were preserved on broken plaster, but their adherence to architectural elements (including door jambs) suggests that most originally appeared around the doorways of earlier and later phases of the structure. The discovery of graffiti containing comparable messages (if not in identical languages) in other Durene buildings confirms the regional convention of writing these types of messages (personal names and remembrance requests) on walls of religious buildings and spaces; most graffiti from other cultic contexts, however, appeared in distinctive locations around shrines and altars.

[4] Some have argued that the scribes who visited the structure were Persian Jews; others have argued for the opposite view, based on Zoroastrian terminology embedded in some of their dipinti. Regardless, the presence of these painstakingly painted messages, which respectfully conform to the contours of specific figures, suggests that Persian visitors to the synagogue, like their local Jewish counterparts, wrote their messages inside the synagogue as a respectful activity, to express their appreciation of the space and of devotional activities conducted inside it.

Additional resources

The Torah and its adornment on Smarthistory.

International Dura-Europos Archive.

Jennifer A. Baird, Dura-Europos (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018).

Lisa R. Brody and Gail L. Hoffman, eds., Dura-Europos: crossroads of antiquity (Boston: McMullen Museum of Art, Yale University, 2011).

Jaś Elsner, “Viewing and Resistance: Art and Religion in Dura Europos,” in Roman Eyes: Visuality and Subjectivity in Art and Text (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), pp. 253–87.

Stephen Fine, Art and Judaism in the Greco-Roman World: Toward a New Jewish Archaeology, revised edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Robin Jensen, “The Dura Europos Synagogue and Christian Baptistery: Early Christian Art and Religious Life in Dura Europos,” in Jews, Christians, and Polytheists in the Ancient Synagogue, ed. Steven Fine (London: Routledge, 1999), pp. 174–89.

H. Kraeling, The synagogue (New York: KTAV Publishing House, 1979).

Ted Kaizer, Religion, society and culture at Dura-Europos (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Michael I. Rostovtzeff, et al., eds., The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters: Preliminary Report of Sixth Season of Work, October 1932–March 1933 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1936).

Karen B. Stern, Writing on the Wall: Graffiti and the Forgotten Jews of Late Antiquity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018).

Karen B. Stern, “Mapping Devotion in Roman Dura Europos: A Reconsideration of the Synagogue Ceiling,” American Journal of Archaeology 114, no. 3 (2010): pp. 473–504.