Imagine yourself at a desk, preparing for an evening of private study. But instead of a chapter of political theory or a thorny set of math equations, what you are facing is a sacred text which, according to Jewish teaching, was delivered directly from the mouth of God to the hand of Moses. Would you dive right in and get to work, or would you need a moment or two to collect yourself?

If you chose the second approach, you would be in good company. In the Jewish tradition, study of Jewish scripture and law (Torah) is equivalent—perhaps even superior—to prayer and requires serious attention. Medieval Iberian Jewish scholar and philosopher, Maimonides, advocated for a measured, reverential approach, “one should sit awhile before prayer in order to direct the mind, and then pray gently and beseechingly.” [1]

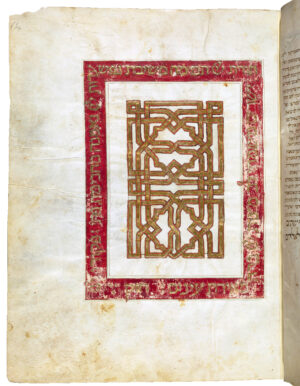

Turning the luxurious opening folios of Kennicott 2, a Hebrew Bible codex made by Joshua ibn Gaon in early 14th-century Iberia, we can see how a ritualized, mindful engagement between reader and Hebrew Bible is supported by the manuscript’s decorative program.

Preliminary texts set in architectural frames. Right: Folio 5r; center: 5v; left: 10r, all from Joshua ibn Gaon, MS. Kennicott 2, 1306, Soria (Spain) (Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford)

The bible opens with a series of preliminary texts set in architectural frames. These prefatory texts provide information to help guide the reader in their study of the texts that follow: the Torah (Five Books of Moses), Writings, and Prophets. In this case, these preliminary texts comprise a list of the 613 Mitzvot and their locations in the text of the Torah.

Right: folio 14r; center: 14v; left: 15r, all from Joshua ibn Gaon, MS. Kennicott 2, 1306, Soria (Spain) (Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford)

But, at the conclusion of these preliminary texts, before we reach the famous words of the first book of the Hebrew Bible—”In the beginning, God created the heavens and earth”—we come across three additional pages, where the decoration intensifies: we find three full-page decorated folios (often called carpet pages) composed of geometric interlaced ornament painted in rich colors.

Joshua ibn Gaon, Folio 14r, MS. Kennicott 2, 1306, Soria (Spain) (Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford)

One of these folios (fol. 14r), contains a mesmerizing full-page golden pattern framed on all sides by a red border in which a golden Hebrew inscription from the Book of Psalms shimmers:

The law [Torah] of the Lord is perfect, restoring the soul;

the testimony of the Lord is sure, making wise the simple.

The precepts of the Lord are right, rejoicing the heart;

the commandment of the Lord is pure, enlightening the eyes.Psalm 19: 8-9

When one pauses to read this inscription, it becomes apparent that the material features of the folio’s design mirror the qualities attributed to the Torah by the words which surround it. The qualities conveyed by the Psalmist—such as “enlightening the eyes”—are mirrored by the golden pattern, which stands out against its unpainted parchment background. Viewed directly, the design is symmetrical and balanced. At the same time, the gaze is invited to follow its turnings and to penetrate its openings as if peering through a window lattice.

Since the Hebrew language is read from right to left, the text begins in the upper right corner of the design, reads across and then down the left margin, then down the right margin, and finishes on the bottom left. In order to read the Hebrew inscriptions that run down the long sides, the reader must rotate the bible, inviting a different perspective of the golden pattern within.

Folios (pages) with butterfly forms highlighted, 14r, MS. Kennicott 2, 1306, Soria (Spain) (Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford)

The composition has two focal points which each resemble open butterfly wings. These are presented horizontally above and vertically below the panel’s midline. If one turns the codex in a clockwise direction to read the inscriptions on the folio’s long sides, these butterfly-shaped forms shift their orientation: now the vertically aligned one becomes horizontally aligned and vice versa. No matter which direction you turn the codex, the reader will always see one horizontally- and one vertically-aligned butterfly shape.

Hebrew Bible, 1300–50, ink, tempera, and gold, 23.7 x 20.1 cm, Castile, Spain (The Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Over a hundred bible codices survive from medieval Iberia—some of which are even more highly decorated than Kennicott 2. The ancient rabbis considered it a mitzvah (positive commandment) for a man to copy his own Torah scroll, so that he might better study the Torah. In medieval times, when Torah scrolls were stored for communal use during weekly worship in the synagogue, this notion was applied to bible codices, which could be used for personal study. Books like Kennicott 2 were commissioned for private study and many contain colophons (a statement naming their patron, or owner, and scribe).

We cannot be certain of the original patron of Kennicott 2; the manuscript’s colophon (which names Moses ibn Haviv as recipient and Joshua ibn Gaon as scribe) appears on a page that may not have been part of the original commission. Kennicott 2 is one of seven bible codices connected to Joshua ibn Gaon’s workshop either because these manuscripts contain his actual name or because they so closely resemble the signed examples.

By medieval standards, Jews were well-integrated into society in Islamic Spain. They spoke and wrote in Arabic and served as important officials in the courts of al-Andalus. Iberian bibles likewise feature designs that display vegetal and geometric forms derived from an Islamicized visual repertoire.

![Geometric ornament in window screens, restored between 1908 and 1914, Puerto de Espíritu Santo, Great Mosque of Córdoba, 10th century (Ariel Fein, CC BY-SA 2.0)[2]](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/espiritu-santo-wide2-300x238.jpg)

Geometric ornament in window screens, Puerta del Espíritu Santo, Great Mosque of Córdoba, 10th century, window screens restored c. 14th century (Ariel Fein, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The interlace ornament in folio 14 recto (fol. 14r) finds parallels in textiles, metalwork, stucco, ceramics, and other media. For example, the window screens (celosias) of one of the gates of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, restored in the 14th century, are similar in their repeated and interlocking designs. In other settings, such as palaces, the geometricized ornament of al-Andalus communicates the authority of its residents. The use of interlocking geometricized ornament in Kennicott 2 was surely also associated with luxury and affirms the owner’s status.

The preparation for the Passover festival, the Golden Haggadah, c. 1320, northern Spain, probably Barcelona (British Library, MS. 27210, fol. 15r)

While Iberian bibles like Kennicott 2 favor interlace imagery, in other Hebrew manuscripts produced in Iberia at the same time, human and animal figures predominate. For example, haggadahs, manuscripts used for the holiday of Passover commonly feature figural imagery. It is thought that such images may have been permissible due to the book’s use in the domestic and family-oriented Passover ritual known as the Seder. Those making Hebrew Bibles—the holiest text in Judaism—were more reticent about employing figures, due to the honor accorded to sacred scripture and Islamicizing forms offered an avenue for decoration and expression without contravening the Second Commandment prohibition against graven images.

Joshua ibn Gaon, Folio 14r, MS. Kennicott 2, 1306, Soria (Spain) (Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford)

Even though they are aniconic, carpet pages like the one discussed above may still be seen as meaningful—perhaps even capable of expressing certain concepts more fully than figural compositions. The decorative program of Kennicott 2 expresses the way people thought about the Bible’s contents. This is an assertion we have seen made, as well, for sacred codices in Christianity and Islam. The opening folios of Christian bibles and Qur’ans also feature full-page decorative designs popularly known as carpet pages. The opening folios of these codices evoke the protective qualities of city-gates, portals, and even the silks once used to wrap separate sections of the holy texts.

Medieval Iberian Jews used the term mikdashyah (Temple of the Lord) when describing the Bible codex in recognition of its relevance to maintaining Jewish life after the Temple in Jerusalem, the site for community offerings and sacrifice, was destroyed by the Romans in the 1st century C.E. Many bibles open with frontispieces which depict the Temple Implements described in Exodus, while others rely on carefully placed carpet pages at the beginning of the Torah, Prophets, and Writings to indicate the tripartite arrangement of the bible, which mirrored the three-part structure of the lost Temple’s architecture. [2] In this way, the decoration of the bible codex presented the notion of its centrality to the survival of the Jewish people until the Temple could be rebuilt in the Messianic age.

The codex of the entire Hebrew Bible was the medium through which medieval Iberian Jews had their most intimate encounter with scripture. The notion of “Torah” as a endless body of knowledge—capable of providing guidance for and limitless readings by its followers—is spurred by the pious engagement of scholars like the person (almost certainly a man) who commissioned Kennicott 2. The abstract ornament we see on fol. 14r of Kennicott 2 participates in this enterprise. It allows the reader to slow down and enjoy the experience of study. It acts as a visual metaphor for the ideation surrounding Torah. It helps us to understand the transition made by the holiest texts of Judaism: from the top of Mt. Sinai to a reader’s desk.