Goodrich Castle, view of the courtyard from the keep

The traditional view of a medieval English castle is that it was designed for warfare, suggesting that medieval lords were perpetually either at war or preparing for it. Until recently castles were mostly studied by military men or at least by men with a military background who had fought in one of the two world wars. Their work on castles extended their interest in warfare back to an earlier period and into an area which had been little studied in comparison with religious architecture. For these men, castles were defined as strongly fortified residences, and both elements, fortification and accommodation, must be present if a building is to be a castle. More recently many scholars have argued that castles had more to do with factors other than warfare, such as dominating the landscape, and that they are best seen as an architectural expression of the social status of their owners.

It is accepted by the archaeologists who have excavated them that castles were introduced to England by the Normans (who came from Normandy in Northern France, and conquered England in 1066). The typical form was a wooden keep (a fortified tower) built on top of a motte (a mound of earth), the whole surrounded by a ditch.

A reconstruction of a Castle has been created at Stansted Mountfitchet (in Essex), by building a fence made of chestnut wood palings around the top of a motte which dates to the time of the Normans, and calling it a “Medieval Experience.” Only a few Norman mottes ever became fully fledged stone castles (the earliest Norman castles were built of timber and earth).

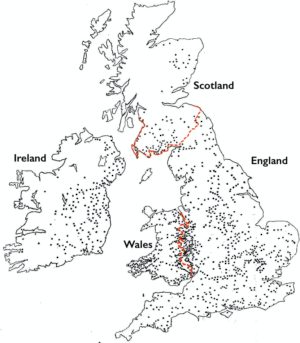

A glance at the distribution map shows that there was a heavy concentration of mottes along the borders between England and Wales and Scotland, but otherwise they were evenly spread across populated areas. Apart from the strategic border castles that were genuinely intended either to guard against invaders or to act as garrisons for raids into Wales, mottes were built in cities, boroughs and practically every town of any size. It was not that the Normans were expecting attacks from the townspeople or even those of the neighboring town. Rather they were building physical statements of their dominance. These mottes are not very high as a rule, and they didn’t need to be to tower over a cluster of surrounding buildings that were little more than huts made of wattle and mud.

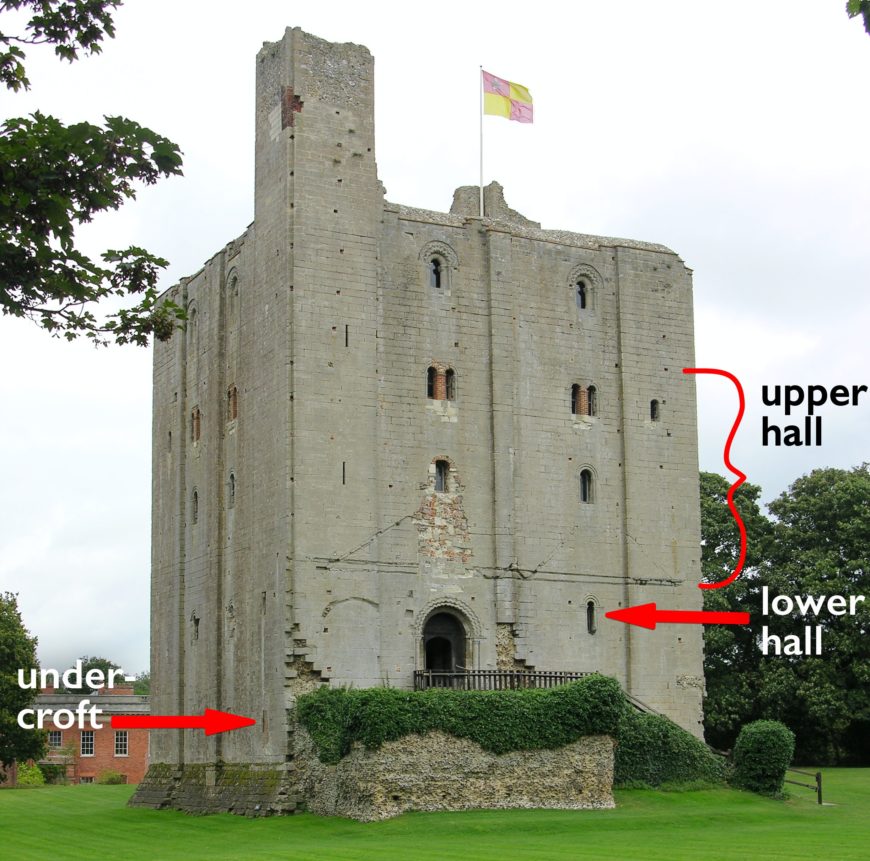

Hedingham Castle

Hedingham Castle in Essex is one of the strongest and most impressive castles in Eastern England, and it was built by one of the richest and most powerful families, the de Veres, Earls of Oxford, most probably in the 1140s. It was an expensive project: there is no suitable local stone, and the high-quality limestone used to build it had to be carted eighty miles from the quarries at Barnack in Northamptonshire. Its tall keep rises to a height of almost 100 feet and dominates the flat surrounding landscape for miles in every direction. This business of height is important. The taller a building, the less stable it is. A genuinely defensive building should be low and squat. But at Hedingham visual prominence is the important factor.

A close examination of the keep shows that a lot of the height is fake.

There is an undercroft (a lower hall at the level of the main doorway), and a double-height upper hall with two rows of windows, and that is all. The row of windows at the top were originally above the roof so that this whole upper storey was open to the sky. It was later roofed in and called the dormitory, but the roof is modern, and the inner walls were never plastered because they were outside.

The false upper storey was not unusual in the Norman period—the White Tower, William the Conqueror’s keep at the Tower of London, was just the same.

This is not the whole story, of course. Castles were luxurious residences too. The luxury is not usually obvious because most castles are ruined nowadays, but the evidence is there to be found. At Hedingham there are richly chevron-decorated arches, fireplaces with carved capitals. and plastered walls, sometimes with traces of painted decoration still surviving.

Rochester Castle

Castles could also be genuinely defensible, but not without preparation and a special effort. During the Barons’ War against King John in the early thirteenth century Rochester Castle in Kent was held by a large garrison of about 100 of the barons’ men.

Rochester Castle was reputed to be the strongest castle in the kingdom—a coastal castle genuinely built for defense. It was besieged by the king for almost fifty days by a large force with engines, battering rams and crossbows, but held out.

Eventually the king employed miners with picks to dig underneath the foundations, propping up the tunnels with timbers, and then setting fire to them using pig-fat to feed the flames. The tunnels collapsed and the tower above them fell, but the defenders continued to hold out in the ruin until they were starved out. Later, however, the barons called on the help of Prince Louis of France, who landed in Kent and proceeded to take all the chief castles of south-east England in rapid succession: Berkhamsted, Cambridge, Colchester, Hertford, Norwich, Orford, Winchester, Hedingham and Pleshey.

This suggests that castles could resist a siege, but only under special circumstances, and those include siting—Rochester is at the mouth of the River Medway, which limits the attackers’ means of approach—and it had a large garrison as well as defensive architectural features. These features could include ditches or moats crossed by bridges with removable central sections, or gatehouses with drawbridges and portcullises, battlements with walkways and machicolations (an opening through which stones or burning objects could be dropped on attackers), and plans designed to make would-be invaders into sitting targets by ensuring that the only access route to the castle was exposed to archers on the battlements. This could be done by building the castle on a man-made or natural hill, and using a moat to slow their progress.

Fortification and Residence

As explained above, the traditional definition of a castle is that it is a fortified residence, and both elements—fortification and residence—are essential before something can be called a castle. The work of recent writers like Robert Liddiard, Oliver Creighton, and Matthew Johnson presents a very different and more complex idea of how castles worked. First there has been a tendency to downplay the military aspect, not least by pointing out that most castles were never under siege. The rules of medieval warfare were designed to avoid genuine sieges. A full-scale siege required enormous resources of men and horses, siege engines had to be constructed and dragged into position, and men committed for weeks or months to operating them and finding suitable ammunition. If the defenders surrendered, they should be allowed to march away unharmed, while the attackers gained only a ruined castle. In practice a siege was usually unnecessary because castles could simply be bypassed by invading forces wishing to advance.

John Goodall has suggested a new definition of a castle as “the residence of a lord made imposing through the architectural trappings of fortification, be they functional or decorative” (Goodall, 2011, p.6). This introduces the idea of fortification as an architectural style, which has much to commend it.

Goodrich Castle

Goodrich Castle in Herefordshire is strategically placed on a sandstone outcrop overlooking the river Wye, near the border between England and Wales. Goodrich reached its full medieval development in the fifteenth century. It was never under siege or serious attack until the English Civil War of the seventeenth century.

To properly understand the way castles worked it is important to try to see them as their users saw them, which can be difficult because there are always additions and losses and, most importantly, there are no longer any inhabitants.

A knight visits the castle

Let’s try to put ourselves in the position of a medieval visitor of high status — a knight in the fifteenth century.

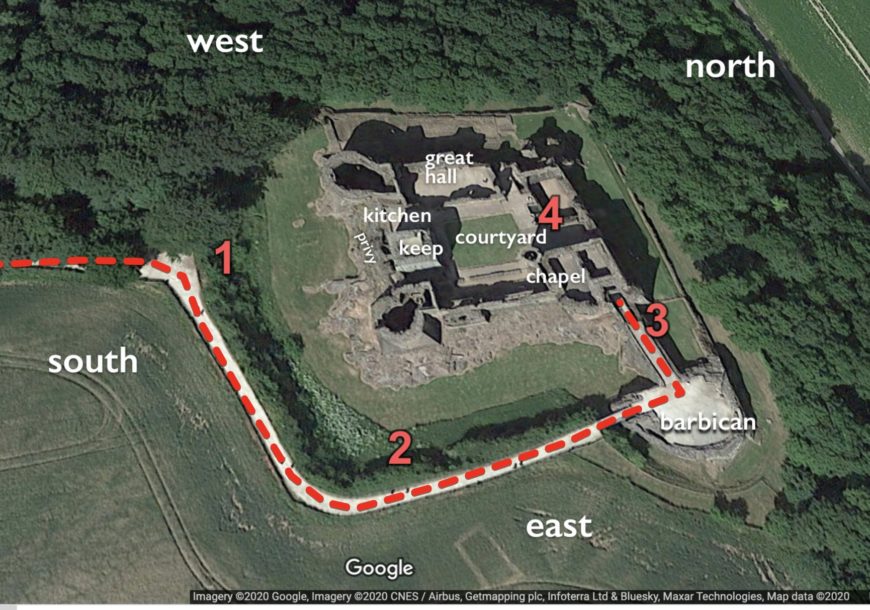

Goodrich: the approach to the castle

As usual there is just one main approach road. The lower orders might do something slightly different, but our knight simply follows the road and is led by the clues it gives. He approaches from the south with his retinue and gains his first view of the castle. In the center he sees a big square building (the keep), obviously older than the rest, which tells him that the castle is ancient—he is visiting a venerable family (in fact the Talbot Earls of Shrewsbury).

View #2: Goodrich Castle, east side (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) (Google street view)

The knight follows the road to the right, around the south-east tower, and sees the east side of the castle, originally reflected in the water of the moat, doubling its size. It has an impressive curtain wall with battlements and arrow slots. Immediately beyond the round corner tower, he sees a newly installed three-seater garderobe or privy — the last word in late-medieval plumbing. Imagine the sight and the smell as he rounds that corner and sees the human waste staining the walls as it drops into the moat. Matthew Johnson has argued that this was an important part of the castle experience, and that all that shit and food waste would have impressed the visitor with the wealth of the occupants and the lavishness of their table. Throughout the ride along the east side, our knight is separated from the castle by a deep moat, but he is observed by watchers on the battlements who will give warning of his approach. An attacking force would be most vulnerable at this stage.

View #3: the approach to Goodrich Castle from the Barbican (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) (Google street view)

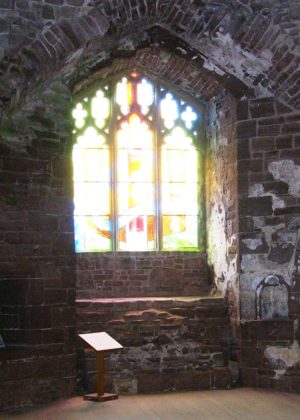

The knight rides on and reaches the barbican—a fortified outwork where he sees the gateway ahead and must dismount. No horses were allowed inside the castle. Retainers dressed in the Talbot family livery take his horse to the stables. All the servants wear the badge of the Lord so our knight can never forget whose roof he is under. To the left of the gateway he sees a chapel — recognizable by its traceried window.

He walks under the gateway and sees murder holes overhead. Perhaps he looks upwards and feels nervous as he sees the portcullis and the murder holes, through which molten lead could be poured on invaders.

These so-called defensive features were not designed to deter a large force (which would probably bombard the walls rather than using the gatehouse), but to impress a single man or a small group.

View #4: Goodrich Castle: the courtyard seen from the gatehouse (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) (Google street view)

The knight emerges into the central courtyard and immediately knows where he is — even if he has never been here before— because the elements of a castle were the same everywhere. The building on the right is the Great Hall, with the dining hall in the centre, the Lord’s lodgings at this end, the high end, and the kitchen at the far end.

As a visitor our knight will use the entrance at the low end, between the kitchen and the hall itself, but he cannot simply walk in. There is a lobby area with benches for visitors to wait until the Lord is ready to receive them.

Goodrich Castle: lobby at the low end of the Great Hall (Great Hall on right, kitchens on left) (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Courtly life was ritualized in this period. The retainers wore their costumes, and the Lord had his part to play like anyone else. A castle was the stage on which social relations were played out, and it was important that all the actors knew their moves and their lines. The similarities between castles were vital to the maintenance of correct social relations, which is why the component parts of a castle were designed to be easily recognizable: the tall window recesses in the Great Hall gave away its function from the exterior, as did the elaboration of the Lord’s private quarters and the traceried windows of the chapel.

A castle visit can be a haunting experience; the crumbling walls evoking thoughts of medieval warfare and lost grandeur. But also, for historians who can read their messages, castles provide valuable evidence of the way life was lived in the Middle Ages. The problem is how to interpret what we see. Churches and cathedrals still operate today; we know what they do and how the various parts fit together as a setting for the liturgy. Even a ruined monastery is not such a puzzle that we cannot work it out. But castles like those I have looked at here function today as tourist destinations and occasionally as wedding venues. They can be settings for pleasure, ritual, and feasting, but not as they were originally conceived. Their value for the historian is that they provide the physical setting for social life in the Middle Ages, and the effort made to interpret them is generously repaid by the understanding these ruins provide.