A conversation with Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris in front of Cimabue, Virgin and Child Enthroned, and Prophets (Santa Trinita Maestà), c. 1290–1300, tempera on wood, gold background, 384 x 223 cm (Uffizi, Florence)

Cimabue, Maestà or Santa Trinita Madonna and Child Enthroned, 1280-90, tempera on panel, 385 x 223 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Virgin Mary with the Christ Child seated on a throne

By the late 1200s, large paintings featuring the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child seated on a throne were a common sight in Italian churches. Larger-than-life panels with this theme, a kind of image that came to be known as a Maestà (meaning “majesty”), were adaptations of traditional Byzantine icons for use in devotion in Western Europe.

Gallery view with Duccio’s Rucellai Madonna (left) and Giotto’s Ognissanti Madonna (right), Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

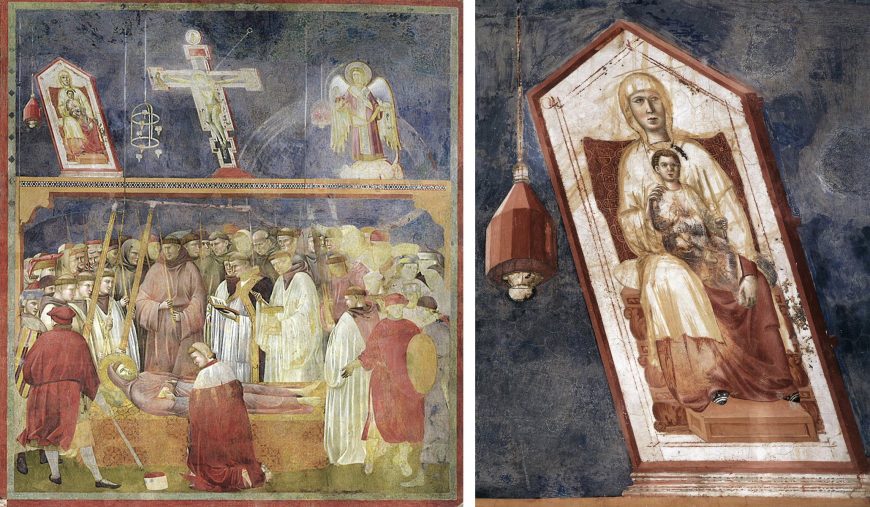

Among the most famous examples are Duccio’s Rucellai Madonna and Giotto’s Ognissanti Madonna. Such paintings may have adorned altars, but they could also have been placed on a beam or wall in the center of a church, perhaps like the painting shown in a fresco depicting the Verification of the Stigmata in the nave of the Upper Church at Assisi.

Left: The Verification of the Stigmata, 1288-1297, Assisi, Upper Church, Basilica of San Francesco; right: detail of the painting displayed on a beam.

Displayed in this way, large Marian images (images of the Virgin Mary) would have been seen by the crowds gathered to hear Mass. Monumental Maestà panels could also be commissioned by lay confraternities—organizations of laypeople who performed acts of piety and service, and gathered to sing hymns of praise to the Virgin. Wherever they might be placed within a church, these imposing, gilded paintings were objects of intense devotion.

View of Cimabue’s Maestà with viewers. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Enthroned Madonna and Child, c. 1250/1275 tempera on panel,124.8 x 70.8 cm (National Gallery of Art)

Santa Trinita Madonna

At an unknown date, probably around 1280, the Florentine artist Cimabue painted a celebrated Maestà for the church of Santa Trinita in Florence. Now housed in the city’s Uffizi Gallery, this massive painting—over twelve feet tall and seven feet wide (12’8’’ x 7’4’’)—features Mary gazing out at the viewer. She gestures toward the child with her right hand, while Christ raises his hand in a priestly pose of blessing, an adaptation of the ancient Byzantine icon type (known as the “Hodegetria”) in which the Virgin Mary points to Christ as the way to heaven.The Byzantine icons that inspired Cimabue and other artists of his day also often included angels posed on either side of the throne, usually shown in much smaller scale than Mary to emphasize her importance (a good example is the painting of the Enthroned Madonna and Child in the National Gallery of Art).

In the Santa Trinita Madonna and other Maestà panels he painted, however, Cimabue makes the angels much larger, and stacks them around the throne so that they seem to be occupying the same space as Mary and Christ. The angels also become interlocutors between the viewer and the holy figures; six of the angels look out toward us directly, while the two in the center gaze at Christ, modeling the pious focus a viewer would imitate.

Cimabue, Maestà or Santa Trinita Madonna and Child Enthroned (detail), 1280-90, tempera on panel, 385 x 223 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Set against a gleaming gold leaf background, Mary and Christ sit on a monumental throne fashioned of intricately carved wood and studded with gems. This throne has often been celebrated by art historians as an example of how Cimabue experimented with perspectival effects. The curved steps of the throne lead the eye back into the fictional space Cimabue creates, making it seem as though the figures occupy real space. The large throne also allows Cimabue to place the Virgin and the eight angels that surround her at the top of the composition, foreshortening the front parts of the throne and bringing them closer to the viewer, creating the illusion of depth on the painting’s flat surface.

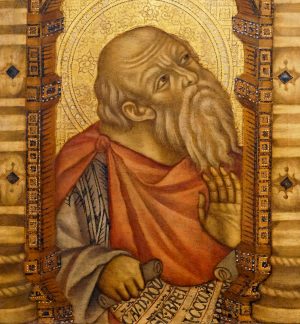

The four figures below

But Cimabue’s most striking and novel element is the inclusion of four bust-length, haloed figures beneath Mary and Christ, enclosed within the arches of the throne’s base. This arrangement foreshadows a trend seen in later altarpieces called a predella—a lateral band of smaller images placed below a larger image. Placed in the foreground, these figures seem to be closer to the viewer than Mary and Christ, further enhancing the sense of three-dimensionality within the painting.

Cimabue, Maestà or Santa Trinita Madonna and Child Enthroned (detail), 1280-90, tempera on panel, 385 x 223 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Cimabue, Jeremiah (detail), Maestà or Santa Trinita Madonna and Child Enthroned, 1280-90, tempera on panel, 385 x 223 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the Santa Trinita Madonna, the men at the base of Mary’s throne are the heroes and prophets Jeremiah, Abraham, David and Isaiah, identified by the scrolls they hold displaying biblical texts associated with each of them (from Jeremiah 31:22; Genesis 22:18; Psalms 131:11; Isaiah 7:14). These figures from the Hebrew Bible (the Old Testament) are included because they each—according to Christian theology—foretold or made possible the coming of Christ (Jeremiah and Isaiah prophesized the coming of the Messiah via a virgin, and Abraham and David were believed to be direct ancestors of the Virgin and Christ). Isaiah and Jeremiah look upwards towards Mary, and each holds an open palm towards the viewer. David gestures similarly, looking towards Abraham, who holds his scroll with both hands and gazes outward from the picture plane. The inclusion of these four men below Mary’s throne glorifies the prophetic heritage and priestly genealogy of Mary and her son.

The Vallombrosans at Santa Trinita

By including these specific figures, Cimabue was perhaps responding to a request from the painting’s commissioners. The church of Santa Trinita was built by a religious reform order called the Vallombrosans, men who lived in community and practiced strict acts of fasting and penance. Founded in the eleventh century by the Florentine knight Giovanni Gualberto, the Vallombrosans sought to bring monastic life back in line with the values of Saint Benedict of Nursia, the founder of western Christian monasticism. In celebrating Saint Benedict, members of the order he founded (the Benedictines), emphasized Old Testament prophets in their literary and artistic traditions. A sixth century text, the Dialogues of Gregory the Great, which includes a biography of Saint Benedict, highlights Saint Benedict’s own prophetic gifts. In the Dialogues, Benedict is compared specifically to King David, legendary author of the Psalms. David is also important in the life of Giovanni Gualberto; his biographers describe how on his deathbed, the saint repeated unceasingly the famous prayer words “of David” from Psalm 23. In Cimabue’s painting, David is the most prominent of the figures below Mary; in contrast to the subdued colors worn by Jeremiah, Isaiah and Abraham, David wears a bright red mantle and a crown. David’s clothing echoes the slightly paler scarlet robes worn by Mary and Christ, and his kinship to Christ himself is reinforced by his position directly beneath the Christ Child.

Cimabue, Abraham and David (detail), Maestà or Santa Trinita Madonna and Child Enthroned, 1280-90, tempera on panel, 385 x 223 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Cimabue’s placement of David and the other figures at the base of Mary’s throne was a completely original visual element, and may have been part of the artist’s efforts to create a new spin on the Maestà in celebration of the Vallombrosans, creating their own “signature” Madonna. Painted at an unknown date in the late thirteenth century, the Santa Trinita Madonna was commissioned at a time when many different religious orders such as the Franciscans and Dominicans were competing for the loyalty of Florence’s wealthy citizens and their offerings. The building of lavish and spacious churches embellished with paintings commissioned by renowned artists were part of these groups’ efforts to keep ahead in the rivalries. The spectacular and innovative Maestà that Cimabue created would certainly have brought new attention and prestige to the Vallombrosans at Santa Trinita.

Additional resources

This painting at the Uffizi in Florence

Holly Flora, Cimabue and the Franciscans (Brepols, 2018), pp. 164-169.

Luciano Bellosi, Cimabue (Motta, 1998), pp. 249-256, 282-283.

Myth and Miraculous Performance: The Virgin Hodegetria

Icons and Iconoclasm in Byzantium

Myth and Miraculous Performance: The Virgin Hodegetria

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”SHTrinita,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re in Uffizi in Florence, looking at a really tall painting. This is the “Madonna and Child Enthroned” by Cimabue, sometimes known as the “Santa Trinità Madonna.” That’s because it was commissioned by a confraternity that was associated with the Church of Santa Trinità in Florence.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:22] When you walk into this room, you are confronted with three enormous images of the Virgin and Child enthroned. Similar in many ways, but also different in many ways.

Dr. Zucker: [0:35] All three panel paintings are enormous. The Virgin Mary is seated on a throne. The Christ Child is seated on her lap, on her left side. He’s shown blessing in each of the three images.

[0:46] Now, there’s a reason that these are similar. The painting that we’re looking at by Cimabue may have been commissioned by this confraternity for laypeople. These are people who were probably excluded from the most sacred part of the church and were intent, with [a] painting like this, on creating a spiritual focus within the more public part of the church that they could occupy.

[1:07] They wanted a painting very much like a painting that had recently been produced for another confraternity. That is Duccio’s “Rucellai Madonna.”

Dr. Harris: [1:15] There was a sense of competition. One of the obvious things that makes this painting different to me is that here, the Virgin Mary, instead of holding Christ with her right hand, gestures toward him to say “This is our savior, this is the path to salvation.”

Dr. Zucker: [1:32] Mary is the largest figure. This is a reflection of her increasing importance at the end of the medieval period, what is often referred to as the cult of the Virgin Mary. In France, in Italy, Mary is increasingly seen as the intercessor, as a bridge to Christ. Christ was too aloof, too powerful, but Mary was seen as more accessible.

Dr. Harris: [1:54] There was a way in which we could appeal to Mary in order to have Christ hear our prayers.

Dr. Zucker: [2:01] Christ seems to be responding to our prayers. His fingers are in the position of blessing. He holds with his other hand a scroll, a reference, perhaps, to the Old Testament, to the ancient Judaic tradition.

Dr. Harris: [2:12] To the idea that the Old Testament prophets had prophesied the coming of a savior for mankind, and Christ is understood as that savior.

Dr. Zucker: [2:22] That’s why Cimabue paints four Old Testament prophets at the bottom of this painting.

Dr. Harris: [2:27] We recognize them as prophets because they hold scrolls.

Dr. Zucker: [2:31] The stylization of the human body and of the throne, of the forms in general, what we’re seeing is an adaptation of the style of the East, of the Byzantine. The long fingers, the impossibly long body, but here, we’re at this critical moment in Italy where there’s an increasing interest in bringing the spiritual down to earth.

Dr. Harris: [2:50] Well, we do have a sense that the throne is somewhat three-dimensional, the angels move back behind the throne, so we do have a sense of a foreground and a little bit of a background. And if we look closely at the gold, it gives us a sense of the folds of the drapery.

Dr. Zucker: [3:08] I see that especially around her forehead. Look at the way that there seem to be folds that crease in and out, where highlights of gold alternate with recessionary areas in shadow.

Dr. Harris: [3:19] I see it especially around her knees, her lap, her belly.

Dr. Zucker: [3:24] But all of those gold striations are also highly decorative, so there is a kind of conflict. There are these efforts at creating a sense of dimension, a sense of volume, a sense of even mass.

[3:35] At the same time, there are aspects of this painting that work against that, that create a sense of two-dimensionality. What we’ll see as we move from Cimabue to his most famous student, Giotto, is an increasing interest in favoring illusionism.

Dr. Harris: [3:48] What we’re seeing here in the late 1200s and in the 1300s is the birth of a new kind of painting in western Europe. This influence from the Byzantine, from the East, the increasing naturalism that we see in Gothic sculpture coming together in Italy, creating divine figures who are newly accessible to us.

[4:10] [music]