The images on this stone coffin mingle Old and New Testament scenes—among the oldest examples of Christian art.

Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus (Sarcophagus with philosopher, orant, and Old and New Testament scenes), c. 270 C.E., marble, 23 1/4 x 86 inches (Santa Maria Antiqua, Rome). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’ve just walked through one of the oldest churches in Rome, Santa Maria Antiqua, and one of the most important objects in it is an incredibly early Christian sarcophagus.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:15] This dates to before the time when Christianity was made legal in the Roman Empire in the early 300s. At this point, Christians are, for the most part, practicing in secret and at times are being persecuted.

Dr. Zucker: [0:29] A sarcophagus is a stone tomb. This was found buried under the church of Santa Maria Antiqua. Let’s start at the left side.

Dr. Harris: [0:37] This is such an unusual figure at first, it seems, because this looks like an ancient Roman god of the sea. It looks like Neptune. He’s reclining on the waves and he’s holding a trident, the attribute of Neptune, the god of the sea.

Dr. Zucker: [0:51] There is some conjecture though, that the trident was also an early Christian symbol and may have referenced the cross.

Dr. Harris: [0:57] The fact that there’s the sea god here makes sense as we turn the corner and we begin to look at the next scene, which shows a ship with two figures in it. This is clearly a storm. We can see the rolling waves beneath the ship. This is the beginning of the story of Jonah.

[1:15] Jonah is a figure from the Old Testament who God has commanded to go to the city of Nineveh and foretell their destruction. Jonah disobeys God. Jonah gets on a ship, and God decides to punish Jonah by sending a great storm.

Dr. Zucker: [1:30] The people on the ship figure out that Jonah is responsible. They ask him, “How can we quiet the sea?” He says, “Throw me overboard.”

Dr. Harris: [1:38] Jonah’s immediately swallowed up by a sea creature. He’s in the belly of that sea creature, sometimes described as a whale, for three days and three nights. For the early Christians, this prefigured or foreshadowed the three days and three nights that Jesus spent in the tomb before the Resurrection.

Dr. Zucker: [1:58] This is particularly appropriate on a sarcophagus.

Dr. Harris: [2:00] It’s about life after death. It’s about surviving death.

Dr. Zucker: [2:04] This is such an odd representation of Jonah. First of all, he’s naked. But he’s also laid out in this wonderful pose with his elbow up, his other arm outstretched, and his legs crossed.

Dr. Harris: [2:16] He’s been borrowed from an ancient Roman mythological figure of Endymion. Endymion is a beautiful youth who the moon goddess loved and who was granted eternal sleep by the god Zeus. The idea of peaceful eternal sleep would make sense on a sarcophagus.

Dr. Zucker: [2:34] What’s going on above?

Dr. Harris: [2:36] We see a tree. We know that toward the end of the story, Jonah rests under a bower. The three sheep are rather mysterious.

Dr. Zucker: [2:44] It’s possible this is a reference to paradise.

Dr. Harris: [2:46] As we move along the sarcophagus, we see a figure who is also very common in early Christian imagery. That is a figure that art historians called an orant figure. This is generally a female figure with both arms raised, and it’s understood as a position of prayer.

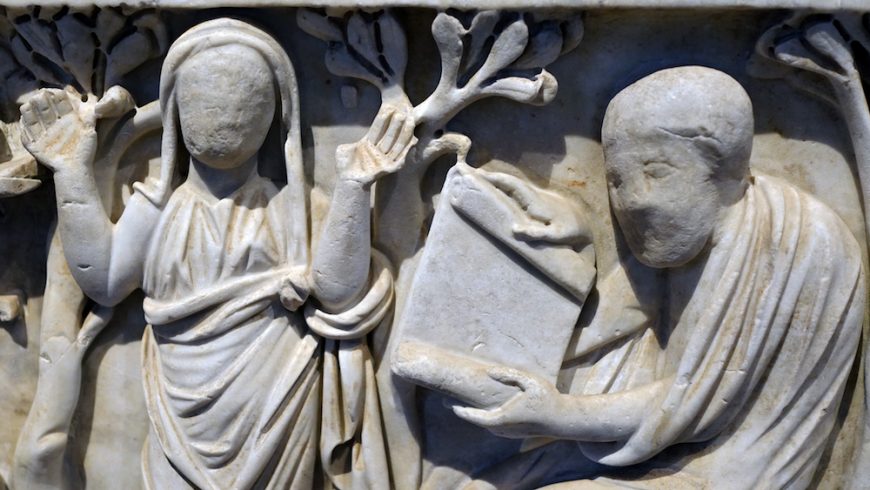

Dr. Zucker: [3:02] These are ideal characteristics for a couple: the man as learned in the scriptures, the woman in prayer, an expression of her piety. It’s also interesting to note that her face and the face of the man seated next to her are unfinished.

[3:16] What might happen is that all of the carving would be done except for the facial features, which could then be finished after it was purchased, so that it could be carved in the likeness of the purchaser.

Dr. Harris: [3:27] This motif of a seated male figure and a standing female figure is derived from, once again, earlier ancient Roman pagan art. We come next to another figure that is very common in early Christian art, and this is Christ, shown as the Good Shepherd. Christ is referred to as the Good Shepherd in the New Testament.

Dr. Zucker: [3:49] If you look at the way that the figure has been carved, although he is fairly squat, you can still see some echoes of the older classical tradition. There is still a trace of contrapposto.

Dr. Harris: [3:59] This is a figure that goes back to ancient Greek art and is here being transformed to mean something very different and specific to the Christian community.

Dr. Zucker: [4:08] That is that the faithful are Christ’s flock and that he will look after them, protect them, and lead them towards paradise.

Dr. Harris: [4:16] As we move toward the right, we have what is perhaps the most recognizable Christian scene. This is a scene of baptism, and we can see the baptismal waters underneath, a bearded figure doing the baptizing, and a small figure that is being baptized.

Dr. Zucker: [4:32] It is possible that this is John the Baptist, and that’s a representation, no matter how small, of Christ. However, it’s also possible that this represents baptism more generally, and that this could be a convert to Christianity.

Dr. Harris: [4:45] What’s perhaps telling is that the figure being baptized looks down at a sheep. If the sheep represent the Christian flock that Christ cares for, maybe that’s an indication that figure is indeed Christ. We also see a dove or a bird in the tree. This may just be a bird in a tree, but it also is more likely a reference to the Holy Spirit, who appears at the time of Christ’s baptism.

Dr. Zucker: [5:13] If we turn around, we come across two additional figures who are holding a net. These are two fishermen.

Dr. Harris: [5:19] Several of Christ’s apostles were fishermen, and Christ referred to the work of the apostles as being the fishermen of souls.

Dr. Zucker: [5:27] I find the motifs on the sarcophagus fascinating because they represent this moment when Christian iconography, when Christian storytelling through images, is being created. This sarcophagus represents such an early example of Christian art before Constantine, before Christianity is decriminalized, and certainly before Christianity had become dominant.

Dr. Harris: [5:50] The iconography will change when Christianity becomes legal, when it becomes the official religion of the Roman Empire, but it’s interesting to think about the birth of a new artistic vocabulary for a new religion in the Roman Empire.

[6:06] [music]

Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus, c. 275 C.E., white veined marble, found under the floor of Santa Maria Antiqua, Rome

Early Christian and Roman (pagan) art

This third century sarcophagus from the Church of Santa Maria was undoubtedly made to serve as the tomb of a relatively prosperous third century Christian. As we will see below, Early Christian art borrowed many forms from pagan art.

The male philosopher type that we see in the center of the Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus (above) is easily identifiable with the same type in another third century sarcophagus (below), but in this case a non-Christian one.

Asiatic sarcophagus from Sidamara, c. 250 C.E. (Istanbul Archaeological Museum, Istanbul) (photo: Richard Mortel, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The female figure beside him in the Santa Maria Antiqua sarcophagus who holds her arms outstretched combines two different conventions. The outstretched hands in Early Christian art represent the so-called “orant” or praying figure. This is the same gesture found in the catacomb paintings of Jonah being vomited from the great fish, the Hebrews in the Furnace, and Daniel in the Lions den.

Left to right: Orant from the Sarcophagus of Sabinus, c. 310-20 (Vatican Museums); Orant from the Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus, c. 270, Santa Maria Antiqua, Rome; Orant from the Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome, fresco, late 2nd century through the 4th century C.E.

Illustration of Dioscorides, late 6th century C.E., illuminated manuscript

The juxtaposition of this female figure with the philosopher figure associates her with the convention of the muse in ancient Greek and Roman art (as a source of inspiration for the philosopher). This convention is illustrated in a later sixth century miniature showing the figure of Dioscorides, an ancient Greek physician, pharmacologist, and botanist (left).

On the left side of the sarcophagus (below), Jonah is represented sleeping under the ivy after being vomited from the great fish. The pose of the reclining Jonah with his arm over his head is based on the mythological figure of Endymion, whose wish to sleep for ever—and thus become ageless and immortal—explains the popularity of this subject on non-Christian sarcophagi (see the detail from a Roman sarcophagus below).

Jonah (detail), Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus, c. 275 C.E., white veined marble, found under the floor of Santa Maria Antiqua, Rome

Endymion (detail), Marble sarcophagus with the myth of Selene and Endymion, early 3rd century C.E., Roman, marble, 28 1/2 inches / 72.39 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Moschophoros, early 6th century B.C.E., marble (Acropolis Museum, Athens)

Another popular Early Christian image appears on the Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus, known as the Good Shepherd (below). While echoing the New Testament parable of the Good Shepherd and the Psalms of David, the motif had clear parallels in Greek and Roman art, going back at least to Archaic Greek art, as exemplified by the so-called Moschophoros, or calf-bearer, from the early sixth century B.C.E. (left).

On the far right of the Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus, we see an image of the Baptism of Christ (below). The inclusion of this relatively rare representation of Christ probably refers to the importance of the sacrament of Baptism, which signified death and rebirth into a new Christian life.

Good Shepherd and Baptism (detail), Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus, c. 275 C.E., white veined marble, found under the floor of Santa Maria Antiqua, Rome

A curious detail about the male and female figures at the center of the Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus is that their faces are unfinished. This suggests that this tomb was not made with a specific patron in mind. Rather, it was fabricated on a speculative basis, with the expectation that a patron would buy it and have his—and presumably his wife’s—likenesses added. If this is true, it says a lot about the nature of the art industry and the status of Christianity at this period. To produce a sarcophagus like this meant a serious commitment on the part of the maker. The expense of the stone and the time taken to carve it were considerable. A craftsman would not have made a commitment like this without a sense of certainty that someone would purchase it.

Orant and Seated figure (detail), Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus, c. 275 C.E., white veined marble, found under the floor of Santa Maria Antiqua, Rome