The octagonal plan references earlier churches and symbolizes regeneration. Was Charlemagne’s throne at its center?

Palatine Chapel (Aix-la-Chapelle), Aachen, begun c. 792, consecrated 805 (thought to have been designed by Odo of Metz), significant changes to the architectural fabric 14–17th centuries (Gothic apse, c. 1355; dome rebuilt and raised in the 17th century, etc.), mosaics and revetment from the 19th century, columns looted by French troops in the 18th century though many were later returned, added back without knowledge as to their original locations in the 19th century. The structure was heavily damaged by allied bombing during WWII and significantly restored again in the second half of the twentieth century. With special thanks to Dr. Jenny H. Shaffer. Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re at the Palace Chapel in Aachen, in what is now Germany. This was the center of Charlemagne’s empire.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:11] If one has experience being in a building as old as this, one expects to see marble that has been worn away, floors to be uneven, parts of mosaics to be incomplete. None of that is here.

Dr. Zucker: [0:24] That’s because much of what we’re seeing, that is, the surface decoration, was added in the 19th century. We walk into a building like this in a sense wanting to walk into the 9th century. Instead, we’re first confronted with 19th century. Our job is to understand this building as it changes through time. Let’s see if we can go layer by layer back to the era of Charlemagne.

[0:49] We know that the building would have originally had mosaic. There would have been stone revetment, but the decorations that we’re seeing here speak to a 19th century aesthetic. This 19th century work was being done at a moment when Germany was unifying into a single state and looked at a building like this as critical for its historical identity.

Dr. Harris: [1:10] That had been challenged by Napoleon. Napoleon conquers much of Europe. The Holy Roman Empire that Charlemagne had founded, ended. Napoleon also stole works of art from the various places that he conquered. Aachen is no exception, he took columns [and] capitals. Most of it was returned after Napoleon’s defeat.

Dr. Zucker: [1:34] One of the problems that the restorers in the 19th century faced is they weren’t sure where things went. And so 19th century restorers had to make decisions without much documentary evidence, and so the columns that we’re now seeing may well not be in the correct location.

[1:50] It would be a mistake to think that the building was in pristine historical condition when Napoleon entered. In fact, the chapel had been remade, most recently in the style that we now call the Baroque.

Dr. Harris: [2:03] Not only was the surface decoration changed, but there were also architectural additions. In the Gothic era, an entire choir was added.

Dr. Zucker: [2:13] We can go even further back in time if we look at the large chandelier brought to Aachen in the 12th century by Frederick I. It’s a magnificent and rare example of a large, round chandelier.

[2:25] Now we can step back to the Ottonians, that is, the dynasty of Holy Roman Emperors that ruled in the years surrounding the turn of the millennium, that is, right around 1000. One of the most remarkable additions of the Ottonians is an ambo, that is, a pulpit that was added by Holy Roman Emperor Henry II.

Dr. Harris: [2:43] It’s no longer in its original location, which would have been much more central. Today, it’s right at the entrance to the Gothic choir that was built. This ambo, even though it’s covered in gold and precious stones and ivory panels, is actually not noticed by most people who come to the chapel.

Dr. Zucker: [3:05] What I’m most struck by is that nothing matches. It’s a collage of different materials, of different scales, of different techniques, as if you’d taken a series of separate treasures and put them together.

Dr. Harris: [3:18] Henry II, through various violent and nefarious machinations, managed to become king and emperor. Because his rule was contested, it is that very mixture of things that demonstrate his power over a vast empire.

Dr. Zucker: [3:36] The elements that are embedded in the ambo likely come from across the empire, and even well beyond. Some scholars have hypothesized that some elements may have come from the Islamic world, specifically from Fatimid Egypt; that there may be elements that come from the Byzantine Empire in the east.

Dr. Harris: [3:53] What’s interesting about those ivories is that two of those panels represent the pagan god of wine, Dionysos. So on this Christian pulpit are decorations that date back to pre-Christian Rome.

Dr. Zucker: [4:08] That would have made sense to the Ottonians, who were using ancient Roman objects as a way of expressing the legitimacy of their rule.

Dr. Harris: [4:15] That they were the inheritors of the Roman Empire.

Dr. Zucker: [4:19] Let’s go further back in time, beyond the Ottonians to the Carolingians.

Dr. Harris: [4:23] It was Charlemagne who built this chapel as part of his palace, along with many other buildings. Today, what remains is just this chapel.

Dr. Zucker: [4:33] Really, all that remains of Charlemagne’s original structure is this very tall, domed interior space and an ambulatory that is octagonal in shape.

Dr. Harris: [4:43] That supports a two-storied gallery. What’s critical is that we are looking at a centrally planned space.

Dr. Zucker: [4:52] Art historians believe that Charlemagne chose this form, which was very unusual north of the Alps, for its symbolic meaning, that this centrally planned structure would recall important historical precedents.

[5:05] The building that is most usually referenced as a precedent is San Vitale in Ravenna. There are some clear parallels. You have a large, open-domed, space. It is a centrally planned space. It is also octagonal. And it is covered with complex decorative revetment and mosaics. This building may have also been recalling Hagia Sophia in Constantinople.

Dr. Harris: [5:28] Some of the elements that Charlemagne used to build this church were taken from Rome and Ravenna. Charlemagne got in touch with the pope and said, “I’m building this new church in my new capital at Aachen. Can I have some columns and capitals, some spolia?”

Dr. Zucker: [5:43] These were ancient columns that Charlemagne brought to Aachen as a symbolic way of saying that his empire was recalling the grandeur of ancient Rome.

Dr. Harris: [5:55] What better way than to bring architectural elements from Rome and Ravenna here to Aachen.

Dr. Zucker: [6:01] Despite the fact that the Ottonian emperor, Otto III, digs up the body of Charlemagne, Charlemagne still remains in this church, entombed in an elaborate golden reliquary that stands in the Gothic extension.

Dr. Harris: [6:15] For me, the historical weight of this building is overwhelming, and it reminds me of how every single person that we’ve talked about felt that historical weight.

[6:27] From Charlemagne, who’s bringing spolia from Rome and Ravenna, to Otto III, who’s digging up the remains of Charlemagne himself, to Henry II, who’s building the ambo to legitimize his reign, to Napoleon, who’s stealing bits of architecture from this building.

[6:46] To the 19th century that wants to recreate what this building originally looked like in the year 800, when it was first built, in order to celebrate a German identity.

[6:58] And today, for all the tourists and worshipers who come to visit. I feel very lucky that this building still stands and we’re able to experience it despite everything it’s been through.

[7:09] [music]

Carolingian art and the classical revival

The Palatine Chapel at Aachen is the most well-known and best-preserved Carolingian building. It is also an excellent example of the classical revival style that characterized the architecture of Charlemagne’s reign. The exact dates of the chapel’s construction are unclear, but we do know that this palace chapel was dedicated to Christ and the Virgin Mary by Pope Leo III in a ceremony in 805, five years after Leo promoted Charlemagne from king to Holy Roman Emperor. The dedication took place about twenty years after Charlemagne moved the capital of the Frankish kingdom from Ravenna, in what is now Italy, to Aachen, in what is now Germany.

In the construction of his chapel, Charlemagne made several strategic choices that linked his building to the legacies of ancient Rome and the fourth-century emperor Constantine. The Emperor Constantine was important because he was the first Christian emperor of Rome. The location for the new building was selected because it was an historic Roman site with hot springs that were used for bathing. The materials used for the chapel also invoked Rome; among them were columns and marble stones that Pope Hadrian permitted Charlemagne to transfer from Rome and Ravenna to Aachen around the year 798. A relic of the cloak of St. Martin was installed in the church at its consecration—the choice of a fourth-century Roman soldier who had a vision of Jesus after sharing his cloak with a beggar was another way to reinforce the link of Charlemagne’s rule with Rome.

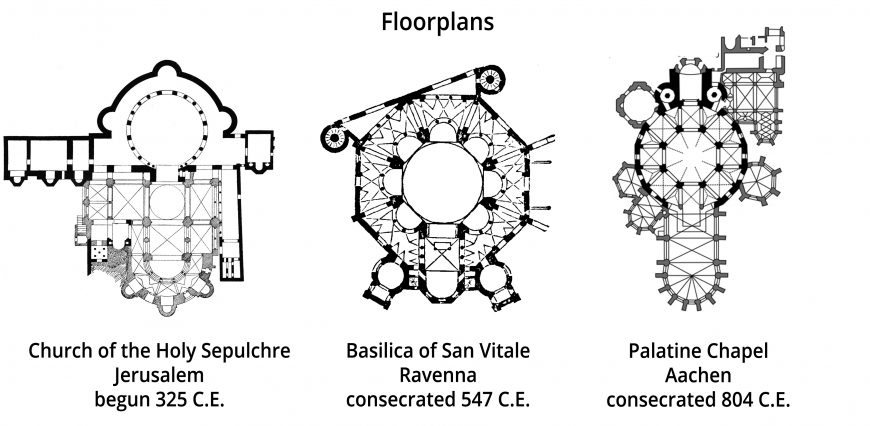

Floorplans of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem; Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna; and Palatine Chapel, Aachen

Two important models (the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and San Vitale in Ravenna)

The chapel’s classical style also referenced its Roman imperial lineage, particularly in its imitation of two significant Christian buildings: the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and San Vitale in Ravenna. The Holy Sepulchre’s building program was started in 325 C.E. by Constantine’s mother, Saint Helena, and completed in 335. The centralized plan and surrounding ambulatory and upper gallery is echoed in the plan of the Palatine Chapel. However, the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem is composed of two main buildings—in addition to the rotunda that covers the tomb is a similar structure over the traditionally-accepted location of the crucifixion. The Holy Sepulchre may also have been the inspiration for the lion-head knockers of the chapel’s bronze doors (below).

Door (detail), Palatine Chapel, Aachen (photo: Bojin, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Because it didn’t receive extensive additions like the Holy Sepulchre, the San Vitale Chapel at Ravenna is probably the best comparison for what the Palatine Chapel would have looked like before its Gothic renovations. San Vitale is a small octagonal church, with a centralized plan and a two-story ambulatory (below).

The octagonal plan of the Palatine Chapel (see plans above) not only recalled that of its two most significant models, but also participated in the tradition of early Christian mausoleums and baptisteries, where the eight sides were understood to be symbolic of regeneration—referencing Christ’s resurrection eight days after Palm Sunday. Its original dome was also based on classical models and bore an apocalyptic mosaic program, consisting of the agnus dei, or Lamb of God (which is, symbolically, Jesus Christ), surrounded by the tetramorph (symbols of the four Gospel writers) and the twenty-four elders described in Revelation 4:4. The agnus dei image was later obstructed by the installation of a chandelier.

Palatine Chapel interior (photo: Velvet, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The octagonal centralized plan of the Palatine Chapel is unique among Carolingian chapels; this may have been because, unlike a longitudinal plan which created a sense of processional direction toward the apse and altar, a centralized plan did not place special emphasis on the altar (and therefore may not have been as effective liturgically for the purpose of a chapel). That said, it does seem to have established an association of Charlemagne with Christ; some scholars believe that Charlemagne’s marble throne (below) was originally located in the center of the octagon on the first floor, that is, directly below the image of the agnus dei, thereby creating a kind of visual link between the emperor and the Christ.

Charlemagne’s throne, Palatine Chapel, Aachen (photo: Berthold Werner, CC BY-SA 3.0)

By presenting his capital at Aachen as a new Rome and himself as a new Constantine through the careful appropriation of late antique artwork and architecture, Charlemagne was not simply making a positive assertion about himself as ruler; he was also implicitly contrasting his reign with that of the Eastern Empire (the Byzantines), a negative stance that was also expressed around the same time in the Opus Caroli Regis contra Synodum (i.e., “The Work of King Charles against the Synod), a detailed response to the Second Council of Nicaea, written on his behalf by Theodulf of Orléans.

Palatine Chapel exterior, Aachen, consecrated 805, Carolingian structure visible (lower two stories) (photo: CaS2000, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Charlemagne’s body was interred in the Palatine Chapel after his death in 814. The building would continue to be used for coronation ceremonies for another 700 years—well into the sixteenth century.

Major additions to the chapel began in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, significantly changing the building’s profile and footprint with exterior chapels. After several fires in the seventeenth century, the dome was rebuilt and heightened.