Kenseth Armstead and Steven Zucker discuss Kenseth’s Surrender Yorktown 1781 (2013) at the Newark Museum

How can we begin to correct the lies of history? Artist Kenseth Armstead suggests a poetic solution.

[0:00] [music]

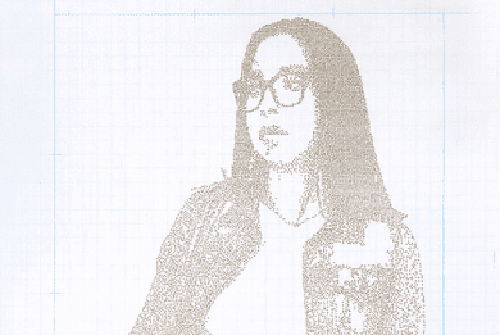

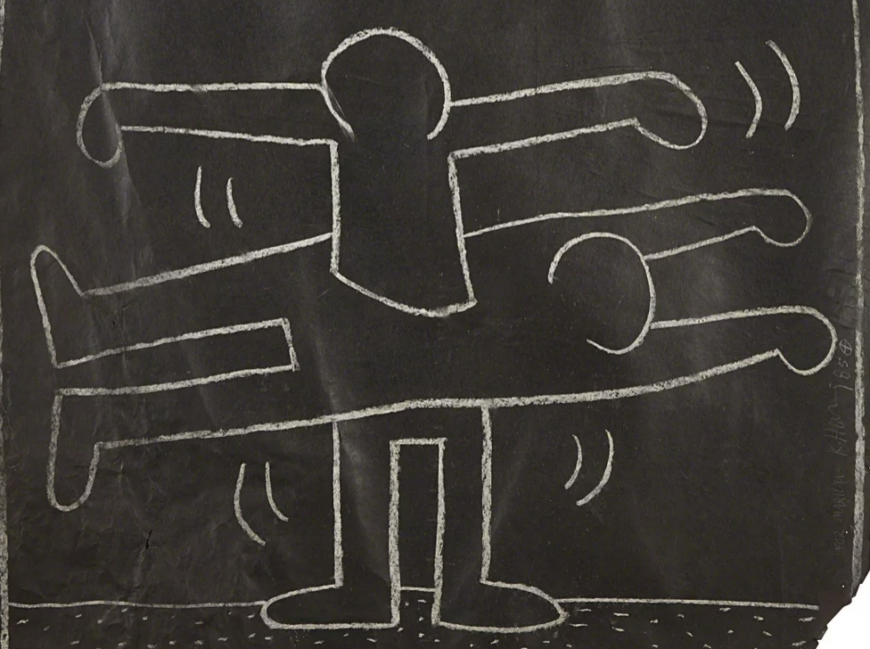

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] I’m in the Newark Museum with Kenseth Armstead, looking at “Surrender Yorktown 1781.” This is not a painting. It’s a drawing, and I see your hand all over it.

Kenseth Armstead: [0:17] The vast majority of history paintings, you can’t see the brushstrokes. In my rendition of history, you can see the hand of the artist.

Dr. Zucker: [0:24] Then what does it mean to take that genre, to take history painting, and to remake it in the 21st century? To take its grand scale but to transform it completely? This is pencil. This is graphite.

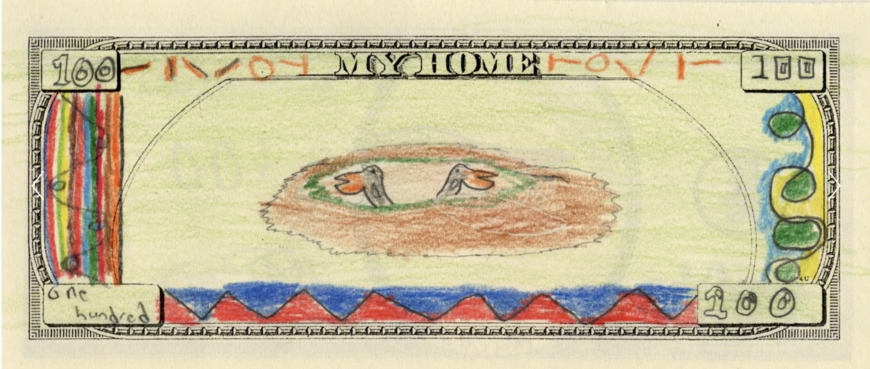

Kenseth: [0:37] The king of France at the time of the American Revolution had invested his ships and capital, literal cash, in our American Revolution, and he wanted a memento of how it is that the American Revolution ended with the British defeated. This, as a Frenchman, made him extremely happy, so he commissioned Blarenberghe to make a painting called “Surrender Yorktown 1781.”

[0:58] What he did was piece together a fantasy of the British surrendering at Yorktown that would satisfy this one patron who needed a memento of his investment in the American Revolution.

[1:10] The original painting by Blarenberghe, it has in it dancing slaves. I doubt very seriously slaves were at the moment of the American Revolution dancing since they weren’t being freed.

[1:20] It has in it landed gentry and it has a landscape that’s lush and beautiful, which wouldn’t actually be realistic after a battle had just concluded.

[1:29] This is the idea of the New World from somebody who’s a fantasist about the New World. They’ve never been, the king of France never been, the painter’s never been. Blarenberghe makes a painting that will satisfy the patron but doesn’t have that much to do with history.

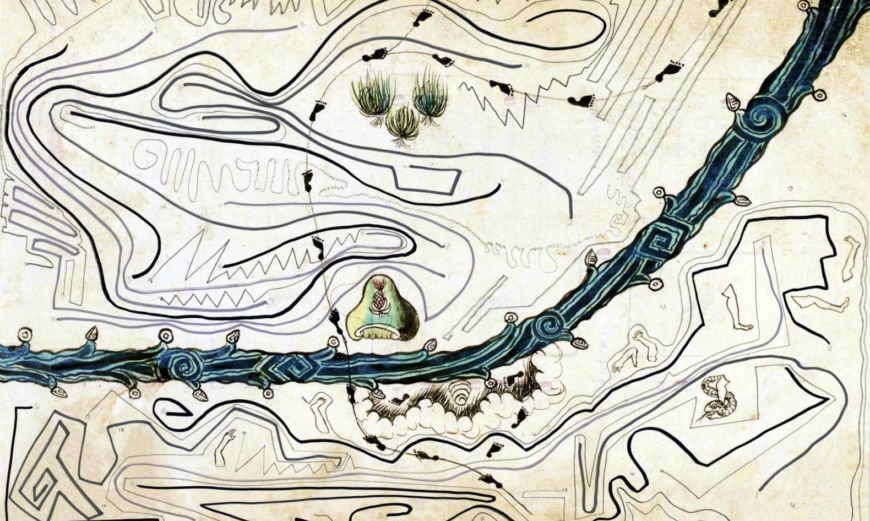

Dr. Zucker: [1:42] There are two kinds of lies at work. There’s the lie of illusionism. We’re looking at a flat canvas, or, in this case, a flat piece of paper. Yet, we have this vast landscape that stretches out before us.

[1:53] But there’s another lie, which is the history, which is the story that’s being told, and you’ve treated this in a completely unexpected way. Instead of trying to imagine what that battlefield looked like populated, you’ve removed.

Kenseth: [2:07] I started out looking at Blarenberghe’s work. I wanted to be honest about it and really work with it. As I started to compose it, I’m like, “Well, that’s fiction, and that’s fiction.”

Dr. Zucker: [2:17] So far, we’ve mostly discussed what you’ve removed, how you’ve stepped away from the illusionistic traditions of history painting and from their falsehoods. But what you have created is this majestic empty space, the aftermath of a terrible battle where hundreds of people died.

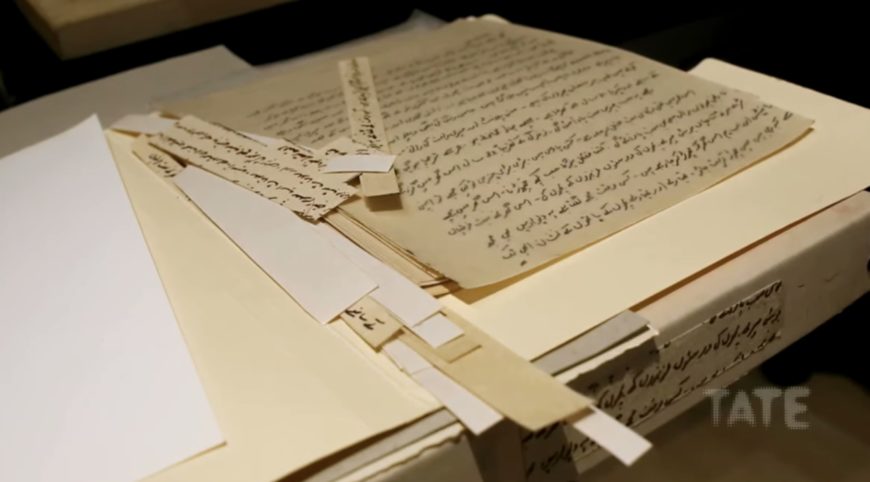

Kenseth: [2:34] The first person to die in the American Revolution is a descendant of Africans. The war would not end without the participation of Africans, specifically James Armistead Lafayette, but also the 20 percent of Washington’s troops. And the French who allowed us the financing and the ships to keep Cornwallis cordoned off so he couldn’t leave by ship. My work allows entry point to explore that all of the histories that we’re given are needing work.

[3:00] They’re all incomplete. When people look at this work in depth, they’ll see layer upon layer of mark making. Making a history painting is not a passive act. It’s a proactive act. You have to go and shape it.

Dr. Zucker: [3:14] You’ve given us a stage set. You’ve given us an open space. You’ve given us an arena that we can repopulate with a truer history.

[3:21] [music]