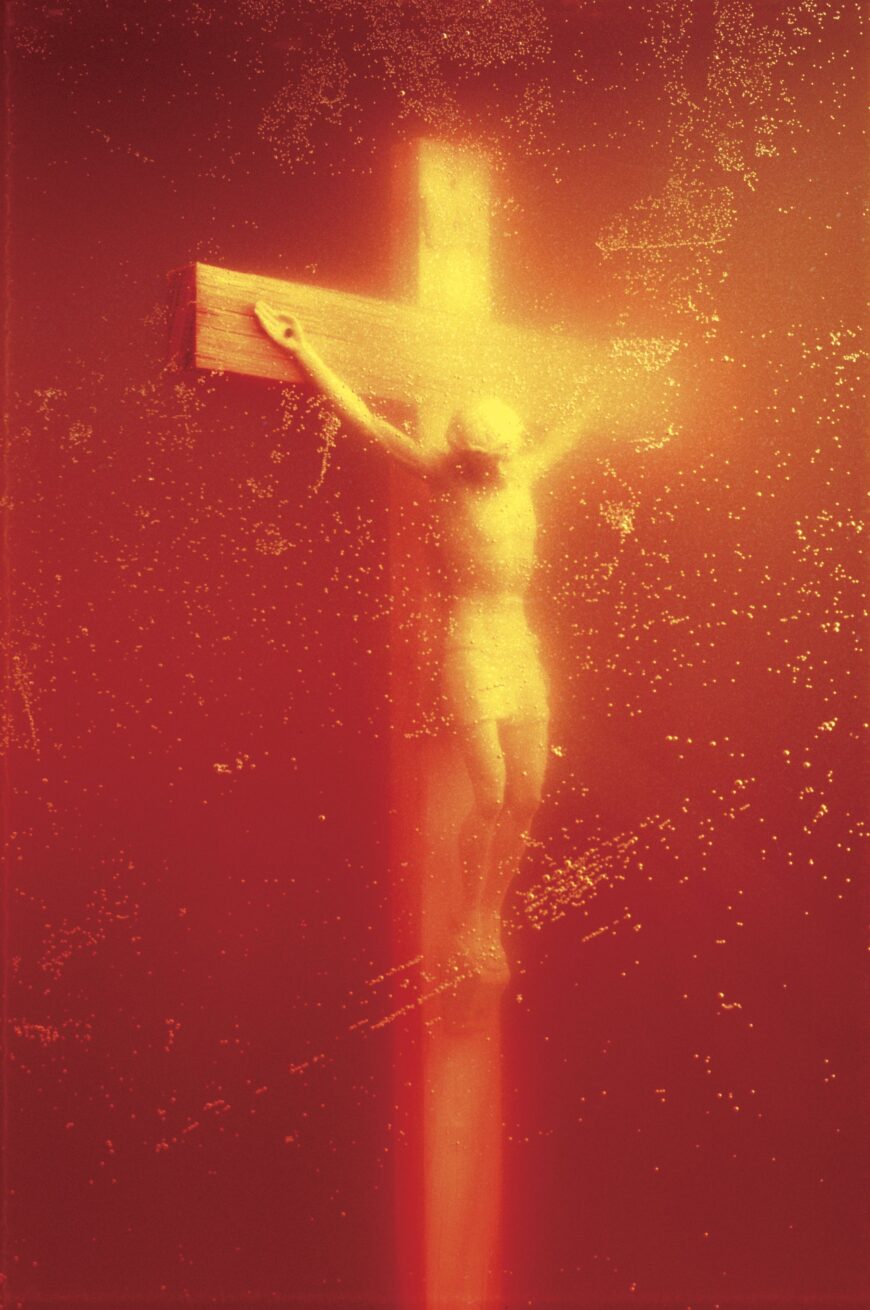

A large glossy Cibachrome photograph shows a reddish yellow surface, darker around the edges and lighter at the center. Contrasted by this backdrop and spread across the picture plane, clusters of tiny bubbles produce an illusion of depth. A crucifix, slightly off center, dominates the space. The object glows in a soft, golden light cast from the right. While the left edge of the horizontal bar and the right hand of Christ appear relatively sharp, the rest of the crucifix is blurred, as if melting away into the reddish mist that seems to engulf the object. The ambiance of the scene claims it as a devotional image. Part of a photographic series by Andres Serrano called Immersion, this image from 1987 is titled Piss Christ.

The photo, along with a selection of other images from the series, debuted at New York’s Stux Gallery in 1987 and Greenberg Wilson Gallery the following year, and was favorably received at both venues. The image was then exhibited at the Center for Contemporary Art in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where the series won the Awards in the Visual Arts competition. The award was partially sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts, founded by the federal government in 1965 to support American artists.

Andres Serrano, installation view of works from Immersions, 1987–90 (photo: © Edward Tyler Nahem Gallery)

When Piss Christ reappeared at another exhibition in Richmond, Virginia in early 1989, however, controversy erupted around the title of the image, especially when the artist admitted that he had photographed a small plastic crucifix placed in a transparent container filled with his own urine. Initially brought to public attention by the right-wing Christian group called the American Family Association, the work was condemned by various conservative organizations that accused Serrano of insulting Christ, the Christian faith, and its followers. What is more, even though only one-third of the $15,000 award had come from the NEA, the offended parties protested the NEA’s lack of accountability for the outcomes of its sponsorship of art projects with public money.

The photograph soon found itself at the core of a nationwide debate over questions of propriety and decency of art funded by taxpayer dollars. Harsh criticisms on the Senate floor later that year, spearheaded by conservative Republican senators Jesse Helms and Alfonse D’Amato, intensified the controversy and secured the scandalous status of this specific photo among the entire Immersion series. Serrano received hate mail, including death threats. For a better understanding of the fierce antagonism and polarization of that debate, it is important to take a brief look at it in the larger context of that era.

Left: Elizabeth Kastor, “Funding Art That Offends,” Washington Post, June 7, 1989; right: Elizabeth Kastor, “Senate Votes to Expand NEA Grant Ban,” Washington Post, July 27, 1989

The culture wars of the 1980s

Under the Republican administration of Ronald Reagan, the 1980s saw a conservative backlash against the liberal reforms of the preceding two decades. So-called trickle-down economics widened the wealth gap; corporate lobbying became a norm in American politics; welfare programs were severely curtailed and labor unions undermined; the “war on drugs,” launched in the previous decade, was now heavily invested in criminalizing minority communities, causing an overwhelming increase of people of color in the prison population; government funding for AIDS research was consistently denied because it was labeled a homosexual disease, which resulted in a devastating epidemic; and military and financial support for corrupt regimes in multiple Central American nations to thwart leftist movements in those countries raised embarrassing questions about U.S. foreign policy.

While the term “culture war” has resurfaced in recent years, it was first widely used in the late 1980s, when conservative and liberal values clashed over allegations of obscenity, blasphemy, and anti-nationalism in art. In addition to Piss Christ and several other cases, a series of photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe (who died of AIDS early in 1989) also came under fire for their explicitly homoerotic content. In fact, the American Family Association took the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati to court in 1990 on charges of obscenity for hosting an exhibition that included the Mapplethorpe images. And because the show, which had begun in Philadelphia, was funded by the NEA, the demand for NEA accountability only grew louder. Since it was clearly stated in the NEA regulations that it would not interfere with the contents of the projects it funded, the question of censorship versus creative freedom became pivotal. The American press and media were inundated with articles and conversations across a spectrum of opinions about the state of American culture. The hardline protesters insisted that NEA be disbanded or its budget slashed as a punitive measure. Even the American art world, though largely opposed to censorship, was often divided over the artistic merits of the controversial images by Serrano, Mapplethorpe, and others.

Serrano has consistently denied any intention to offend anyone with Piss Christ. Instead, he has argued that discomfort or insult caused by the image should motivate one to ponder the violence and ugliness of the actual Crucifixion. Born in 1950 in a Spanish-speaking mixed-race Catholic family, Serrano considers himself a practicing Christian, albeit with an ambivalent relationship to the teachings of the Catholic Church. Instead of faithfully accepting the Church’s views of the body, he chose to experiment with images of body fluids in his photographic practice. His Milk, Blood from 1986, for instance, is a photograph of a diptych of two rectangular containers, one filled with blood and the other with milk. Serrano has insisted that such images represent his experiments with photographic abstraction. Piss Christ from 1987 is executed in the same way but with a container full of urine.

Abject art

Abject art is a trend that emerged in the 1980s and the 1990s. Artists who identified with this genre challenged the prevailing cultural disgust with the aesthetically unacceptable elements, conditions, and functions of the human body, such as defecation and lactating breasts. Their aim was to explore the limits of the vulnerability of the body in social contexts, deliberately provoking discomfort or revulsion as a step toward appreciation of the subtler aspects of the content of the art. While Serrano’s photographs belong to this genre, the abject in his work comes to the fore only via the descriptive title, which exposes his materials and process. Thus, it is the title that is at the root of the allegations against Piss Christ.

The Immersion series, produced between 1985 and 1990, is the culmination of Serrano’s experiments with abject elements in photography. All the photographs show figurative objects—both Christian and Greco-Roman—in fluids that are not always identified. Piss Discus from 1988, the blurred silhouette of a Greek athlete submerged in urine, did not offend anyone; nor did Crucifixion from 1987 where equally hazy figures of Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene flank the crucified Christ. The scandal erupted only when the “sacred” (the crucifix) and the “profane” (urine) came together in the title “Piss Christ.” For many, this combination disrupted the pleasure of the spiritually complacent image and turned it into a symbol of a secular assault on the Christian faith.

Crucifixion (detail), Andres Serrano, Piss Christ, 1987, Cibachrome print, 152.4 x 101.6 cm © Andres Serrano

Legacy

The debate over Serrano’s photograph offers at least two lessons. First, it makes one aware of the difference between seeing an image and knowing about it; the use of language, which situates an image in a broader context, can radically alter one’s visual perception of it. Second, once an image is in circulation, the intent of the artist is all but inconsequential, as viewers project their own values on it to construct diverse meanings. If, as Serrano claims, his work is open to interpretation, then it is difficult to accept his other claim—that he never expected any controversy when he made the image. It seems improbable that he had not anticipated any discontent while candidly disclosing his material and process using one of the most potent religious icons in the world.

After the initial uproar in 1989, Piss Christ was vandalized at an exhibition in Melbourne, Australia in 1997, then again in Avignon, France in 2011. As recently as 2023, there were protests in one of the school districts in Santa Barbara, California, after the photograph was shown in a high school art history class. It was promptly removed from the curriculum. If context plays a crucial role in the impact of content in art, then there is no question that the context created by the alliance between iconography and title in Piss Christ leaves the doors to further discontent wide open.