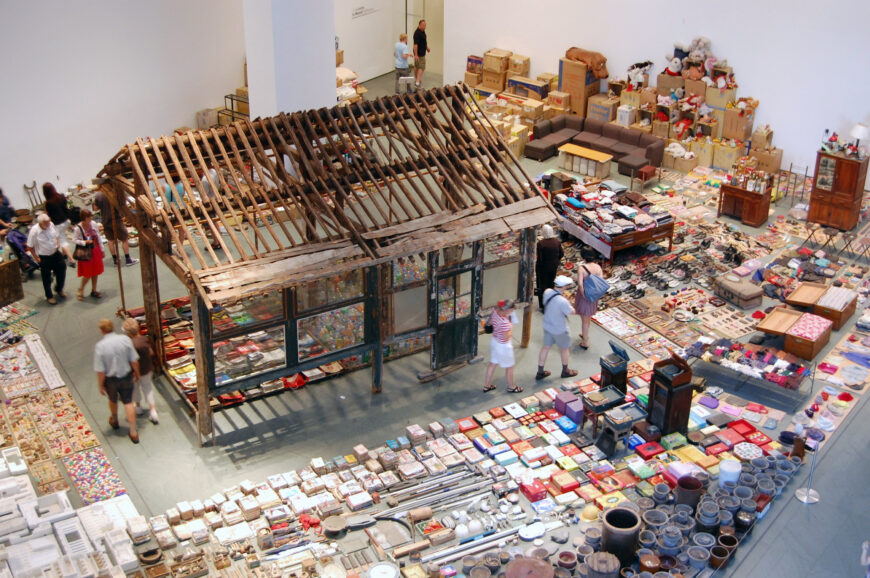

Song Dong, Waste Not, 2005, materials and dimensions variable (Exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2006; photo: Andrew Russeth, CC BY-SA 2.0) © Song Dong

A great number of objects of a wide variety occupy a large area of the floor. The display contains all kinds of household artifacts, from furniture and kitchen implements to used pens, pencils, and shoes. In the middle stands a skeletal structure of a house. While at first glance the scene might resemble a flea market, closer inspection reveals a level of complexity in the grouping and arrangement of the items not found in commercial displays of products. It is an installation by the Chinese artist Song Dong called Waste Not. First exhibited in Beijing in 2005, the work has since been recreated at numerous international venues.

Survival amidst tragedy

Such an expansive display of industrially made consumer products is likely to lead a contemporary Western audience to assume that Waste Not addresses the negative impact of capitalist production and consumption on the planet’s ecology and environment. Yet the primary goal of the installation is to offer an intimate look at a specific individual’s personal struggle for survival amidst a nation’s socioeconomic, political, and cultural changes and her family’s attempt to honor that struggle. The items used in the work come from the personal possession of Song’s mother, Zhao Xiangyuan, who saved literally everything she used and inherited over several decades.

Song Dong’s grandfather was imprisoned for his loyalty to the rulers of China who were vanquished by the Communist revolution in 1949. Later, during Chairman Mao’s devastating Cultural Revolution, which attempted to radically transform all aspects of Chinese society, Song’s father was targeted as a “counter-revolutionary” and sent to a “re-education” camp until 1978. Born in 1966, the year the Cultural Revolution began, Song was primarily raised by his mother.

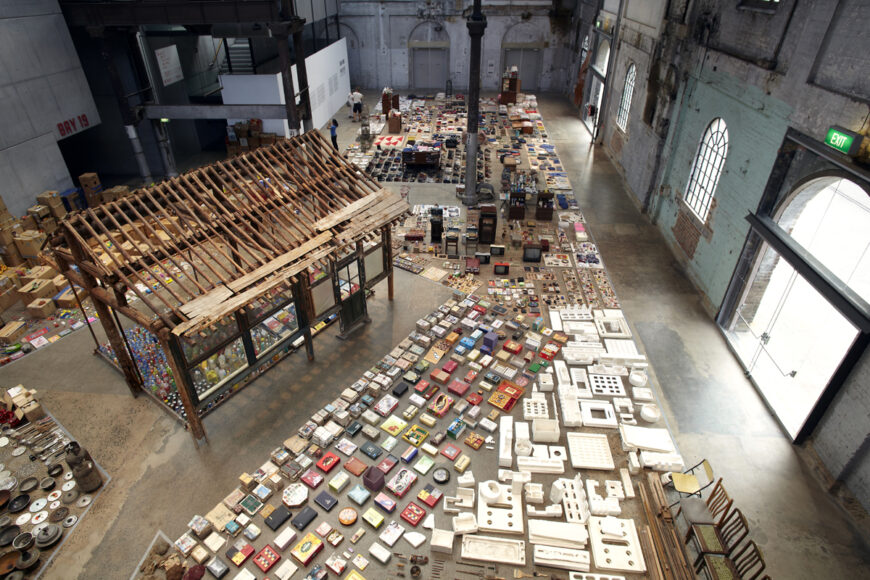

Song Dong, Waste Not, 2005, materials and dimensions variable (Exhibited at the Barbican Centre, London, 2012; photo: Tom Page, CC BY-SA 2.0) © Song Dong

Affected by the decline of her family’s economic status during those years, Zhao saved all used household items, including containers of expended products, such as toothpaste tubes and empty plastic bottles. After Song’s father passed away in 2002, her habit of hoarding became more intense due to deep depression caused by her grief. Her accumulation, which she adamantly protected, grew exponentially in the following years. As Song has remarked, his mother’s compulsion to fill her domestic space was, in fact, a tragic attempt to fill her own emptiness.

A public expression of private life

Song, who had shifted from conventional painting to conceptual art practice, persuaded his mother to collaborate with him on an installation project using her possessions. The phrase Waste Not is a translation of a pithy expression in Mandarin underscoring the virtue of frugality. The vast number of objects in the Beijing show were grouped not by formal properties, such as color, shape, or texture; instead, drawing on the early scientific practice of classification known as taxonomy, Song separated them by type and function. Not only did such a public expression of Zhao’s private life introduce a structure and order to her personal histories and memories, but it also generated conversations with many exhibition visitors from her own generation who could relate to her entrenched obsession with frugality. The enhanced social interactions with them brought her a sense of purpose. According to Song, Zhao was the artist in the project and he, her assistant.

Song Dong, Waste Not, 2005, materials and dimensions variable (Exhibited at Carriageworks, Sydney, 2013; photo: Carriageworks, CC BY-SA 3.0) © Song Dong

After a brief hiatus following Zhao’s death from a tragic accident in 2009, Song continued to exhibit the work, collaborating with his elder sister Song Hui and his wife Yin Xiuzhen, herself a renowned artist. Beginning at San Francisco in 2011, over 10,000 items have been shown in the second phase of Waste Not, with occasional compositional variations in its several iterations around the world. The work has since become both a shrine honoring Zhao’s memory and a symbol of bonding for the family.

Shoes are a case in point. Women in pre-revolution China had to wear shoes of smaller sizes because small feet signified feminine beauty. Compared to Zhao’s shoes, therefore, those inherited from Song’s grandmother are unusually small. Song’s sister’s shoes, on the other hand, are more modern but also cheaper products of the sort available during the Cultural Revolution. In contrast, the shoes worn by his niece are fancier and more expensive. The presentation of footwear thus bridges four generations of women in the family. In San Francisco, additional objects came from the other members of the family, a structure resembling Zhao’s house was introduced within the display, and photo-based works by Song addressing family ties were included.

Song Dong, Waste Not, 2005, materials and dimensions variable (Exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2006; photo: C-Monster, CC BY-NC 2.0) © Song Dong

The installation is based entirely on strategies of arrangement, as nothing in it, except for the frame of a house, is made by the artist. Kitchen utensils like ladles and spoons are separated from noodle-strainers; the individual items in each group are carefully placed on the floor, apart from one another, recalling displays of archeological specimens. The same strategy is evident in the organization of flattened toothpaste tubes, watches, bottle caps of various sizes and colors, and rows of markers, pens, and pencils, all in their assigned place. Bowls, pots, and pans, on the other hand, are grouped in their own area, separated from numerous flowerpots in another zone. Tied stacks of books and magazines sit next to several collapsible umbrellas, not far from an assortment of hammers and other household tools. Many pieces of fabric are neatly folded and stacked on a bed and inside a cabinet, whereas other fabrics are rolled, tied, and organized in individual rows on the floor, adjacent to a large heap of plastic shopping bags folded into triangles. A row of unmatched chairs marks one edge of the installation area, along with four television sets. With no aisles through the display, visitors can only walk along its boundaries. The itinerant character of the project is reinforced by the packing boxes stacked along the wall, displaying stuffed toys. All this constitutes a tiny fraction of the entire inventory.

Song Dong, Waste Not, 2005, materials and dimensions variable (Exhibited at the Barbican Centre, London, 2012; photo: Tom Page, CC BY-SA 2.0) © Song Dong

The objects exist in an intriguing space between the domains of the private and the public, as their impersonal identity as manufactured products is compromised by the unmistakable traces of use on every single one of them; the shabby, worn-out commodities carry memories of personal touches, evoking a narrative about human resilience and survival. What is more, the appeal of the mere ordinariness of the items is holistic, since visitors move along the contours of the installation, unable to examine them individually. While such a visual experience may provoke reflections in a viewer on their own relationship with material consumption, the designs, brands, and implied functions of many of the products meant for use in China should also appear somewhat culturally distant to a foreign audience.

Engaging the archive

There is no question that Waste Not is strongly grounded in the mode of art practice that addresses the archive, not least because Song is currently developing a digital archive of the exhibits. Archives were conventionally seen as neutral repositories of knowledge that had existed for centuries. Around the 1970s, however, a revisionist approach to culture identified the archive (as well as the museum) as an artificial entity. An archive, in other words, has its own history and politics; the context of its origin is integral to the content it preserves; and due to this contingency, its structure, content, and purpose are subject to change. This new understanding led such artists as the Belgian Marcel Broodthaers, the German Hans Haacke, and the French Christian Boltanski to experiment with archival properties in their own works, paving the way for the artists of a younger generation. The Americans Mark Dion, Fred Wilson, and Sarah Sze, for instance, have employed various aspects of archival principles to address issues that have seemed urgent to them.

Song Dong, Waste Not, 2005, materials and dimensions variable (Exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2006; photo: C-Monster, CC BY-NC 2.0) © Song Dong

Not only does Waste Not rightfully belong to this legacy of art practice of engaging the archive, but it reinterprets that practice in the context of modern Chinese history and culture. Constructing a spectacle out of the least spectacular, the mundane, Song Dong has made a substantial archive out of his mother’s large accumulation that redefines her history of hoarding—a socially awkward and psychologically questionable habit—into a rich site. The site enables him and his family to confront their own history, shaped through the aspirations and tribulations of modern Chinese society, and reaffirm their solidarity.