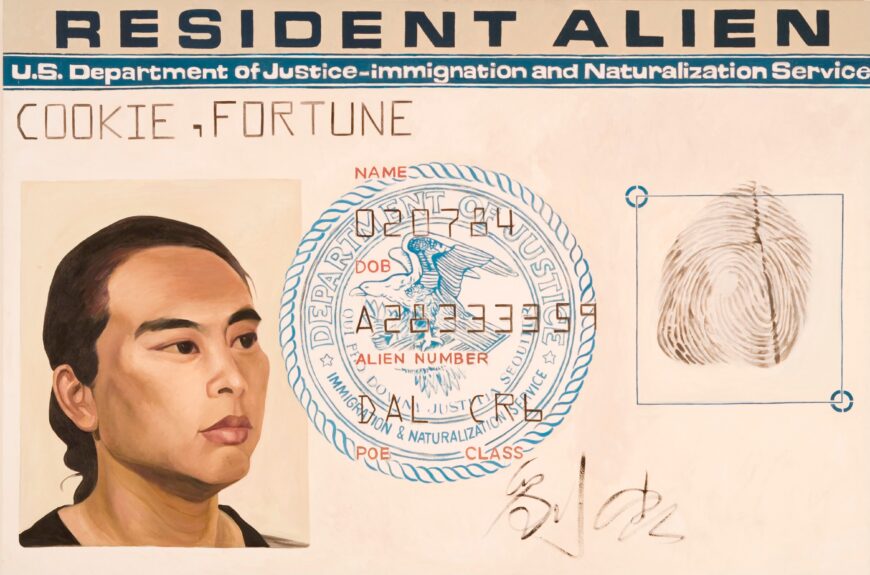

Chris Ofili, The Holy Virgin Mary, 1996, paper collage, oil paint, glitter, polyester resin, map pins & elephant dung on linen, 243.8 x 182.9 cm © Chris Ofili

Sensation

When the personal collection of British advertising executive and art collector Charles Saatchi went on tour in an exhibition called Sensation in 1997, viewers should have known to brace themselves for controversy. The show presented a cross-section of shocking work by a brash new generation of “Young British Artists,” including, for example, Marcus Harvey’s portrait of convicted child-murderer Myra Handley, and pornographic sculptural tableaux by Jake and Dinos Chapman. In London, the museum was picketed from day one, but the media attention eventually ushered in record turnouts.

In October of 1999, Sensation opened at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, where it was Chris Ofili’s iconic painting, The Holy Virgin Mary that incited the most heated debate. Mayor Rudy Giuliani threatened to close the city-funded institution on the grounds that this artwork was offensive to religious viewers. Two months later, the painting, which rests upon two large balls of elephant dung, was desecrated by an elderly visitor who smeared white paint over its surface, claiming that the image was “blasphemous.”

At first glance it seems easy to discern why the painting raised a few eyebrows: the inclusion of real shit and collaged pornography might be enough to offend conservative viewers. However, Ofili’s work is more nuanced than it appeared to his detractors; the piece reflects on art historical precedents while addressing identity politics, religion and pop culture. To grasp its complexity, one must look beneath the surface—as dazzling and shocking as it may be.

Chris Ofili, The Holy Virgin Mary, 1996, paper collage, oil paint, glitter, polyester resin, map pins & elephant dung on linen, 243.8 x 182.9 cm © Chris Ofili

Iconic or iconoclastic?

Set against a shimmering gold background comprised of carefully placed dots of paint and glitter, the central figure in Ofili’s painting stares directly at her beholder, with wide eyes and parted lips. Her blue gown flows from the top of her head down to the amorphous base of her body, falling open to reveal a lacquered ball of elephant dung where her breast would be. Collaged images of women’s buttocks surround the Virgin; cut from pornographic magazines, they become abstract, almost decorative forms that refuse to signify until confronted up-close. The two balls of dung beneath the canvas are adorned with glittering letters spelling out the work’s title.

Formally, the use of gold and the front-facing Virgin link the work to Medieval icons, making the vulgarity of the pornographic images all the more stark. Yet, the artist claims that the sacred and the profane are not always opposed, even in traditional religious art:

As an altar boy, I was confused by the idea of a holy Virgin Mary giving birth to a young boy. Now when I go to the National Gallery and see paintings of the Virgin Mary, I see how sexually charged they are. Mine is simply a hip hop version.

Race, religion, and representation

It is perhaps Ofili’s final statement above that indicates the source of his critics’ anxieties. As Carol Becker has explained, Ofili is “transforming the Holy Virgin into an exuberant, folkloric image. (…) probably most controversial of all, he made his own representation of the Virgin, defiant of tradition.”[2] The “parody-like African mouth” and exaggerated facial features call attention to racial stereotypes, as well as to the assumed whiteness of biblical figures in Western representations. Ofili’s icon asks us to confront the possibility of a black Virgin Mary. Other works express Ofili’s interest in black culture more explicitly: paintings like the Afrodizzia series and No Woman No Cry make references not only to hip-hop and reggae but also to contemporary racial politics.

The triumph of painting

While his works pay homage to iconic black celebrities such as James Brown, Miles Davis, and Muhammad Ali, they are also just as much about the act of painting. With their psychedelic patterning, bright colors and textured surfaces, the images express Ofili’s desire to “get as deeply lost as possible in both the process of painting and the painting itself.”[3]

From his beginnings, the artist was passionate about the medium, even as painting grew out of favor in the wake of postmodernism. He enrolled at the Chelsea School of Art where he developed an expressionistic style, but his work really started to mature after an oft-mythologized trip to Africa.

Ofili was born in Manchester, England to Nigerian parents. When he was awarded a British Council grant in 1992, however, he ventured not to their home country but to Zimbabwe, in southern Africa. There, he was inspired by the abstract motifs found in San rock painting; these graphic marks found their way into the swirling backgrounds of his later compositions.

In Zimbabwe he also discovered elephant dung, and experimented with using it as an aesthetic medium, sticking it onto the surfaces of his canvases. As he later recalled, “it was a crass way of bringing the landscape into the painting,” as well as a nod to modernist art history through the dung’s status as a found object.[4]

The following year, back in Europe, Ofili was already at work with his new material. He staged a performance in Berlin and London entitled Shit Sale, a nod to the American artist David Hammons’ Bliz-aard Ball Sale of 1983, and later produced a work on canvas simply titled Painting with Shit on It, from which his mature style eventually emerged.

Combining visual pleasure with a conceptual practice

Ofili’s work is as formally-motivated as it is political. The artist did not only return to painting, he returned to decoration and visual pleasure, at a time when art was expected to comply with the more cerebral aesthetics of postmodernism. Perhaps his attraction to gaudy bright colors, earthy materials and glittering surfaces, paired with the highly conceptual stakes of his project, reflects another blending of sacred and profane, regarding the conservatism of the art world. By incorporating high and low art forms, historical narratives, religion and pop culture, The Holy Virgin Mary represents a deeper inquiry than the spectacle of Sensation would imply.