Christina Fernandez, 1910, Leaving Morelia, Michoacán Mexico from María’s Great Expedition, 1996, gelatin silver print (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles) © Christina Fernandez

A young woman stands against a dark background, toward the right edge of the composition. A rebozo (shawl) wrapped around her torso is held tight by her interlocking hands. Her gaze extends beyond the photo’s frame. She appears preoccupied with whatever lies beyond, contemplating what is ahead: a possible future. The staging of the black and white photograph resembles a film still of a Hollywood Western, suggesting an epic and potentially dangerous but heroic tale is about to be told.

This image is the first in a series of photographs in artist Christina Fernandez’s multimedia installation, María’s Great Expedition. The installation is composed of a map and six photographic prints displayed in a horizontal sequence. Below them is a ledge on which rests caption text for each photograph in both Spanish and English. Though not explicitly stated in the captions, the installation is based on Fernandez’s maternal great-grandmother, María Gonzales, who is portrayed by the artist herself in the photos, making them portraits and self-portraits at the same time.

The captions are based on biographical information Fernandez gathered from family—memories and lore—as well as broader historical research. They commingle fiction and fact, others and self. Like in many immigrant families, physical mementos like photographs were scarce. In the few snapshots of her family that were preserved, Fernandez noted a physical resemblance and, moreover, saw other immigrants in María’s life story.

The first caption notes that in 1910, at 14-years old, María left the ranch she lived on outside of Morelia, Mexico. She was heading into the “recently expropriated U.S. Southwest,” a reference to the forced transfer of land between the two countries following the Mexican-American War. The expropriation meant that people living on this land, often for generations, were suddenly cleaved into U.S. and Mexican territory, regardless of their desire or identification. María is an individual who navigated these forces much bigger than her or her family, and more expansive than any border could contain. She would, as Fernandez’s project posits, navigate these times with cunning, self-determination, resilience, and dignity, encapsulating in her narrative the grueling stories of many immigrants.

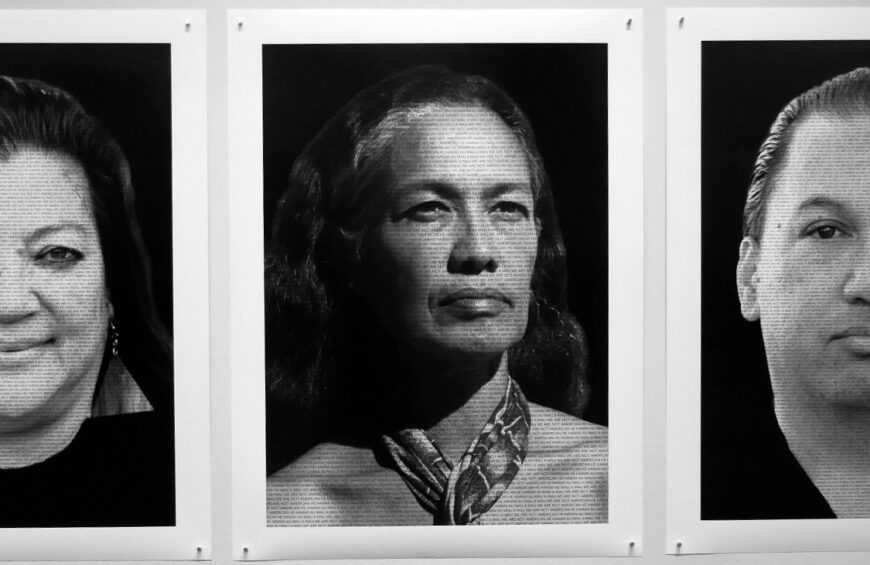

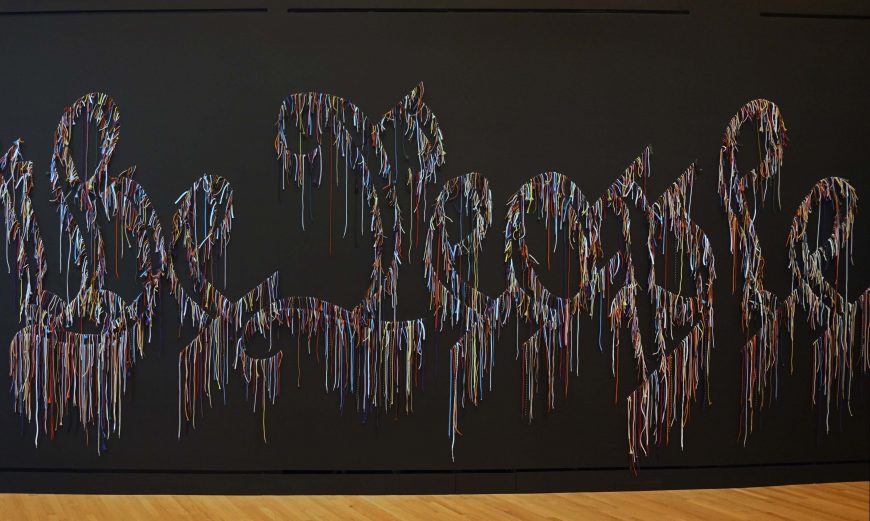

Christina Fernandez, María’s Great Expedition, 1995–96, photographs with bilingual narrative (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles) © Christina Fernandez

How do you tell a story that is universal yet particular? One that combines the gritty detail of your own lived experience with collective and less easily graspable narratives, be they familial, national, or even global? These collective narratives, which help us understand how we got to where we now stand and see the world, often take place long ago and are half-remembered, perhaps even intentionally erased.

Museum

To begin to answer these questions, Fernandez chose to create an artwork that recalls a museum exhibition. Since the 19th century, the museum has been a key component for building and maintaining national identity, which depends on audiences to envision themselves as part of a larger community. Museums collect, preserve, display, and narrate objects and documents that are deemed of value and representative of the nation, “American Art” for example. Art and the stories they tell that are not housed in this space can be perceived as falling outside the borders of established categories. By appropriating this form of display, Fernandez draws attention to this exclusion. In treating María’s story as worthy of museum display, Fernandez places it on the museum’s “marble pedestal” and—at the same time—chips away at that pedestal.

Fernandez created María’s Great Expedition for an exhibition in 1995 titled From the West: Chicano Narrative Photography at the Mexican Museum in San Francisco. Several of the artworks included explored how the concept—myth, really—of the “American West” was constructed through photos. In other words, when someone says the “American West” and you think of wide-open land and endless opportunity—or Indigenous dispossession and genocide—that idea, whether based in fact or fiction, was developed in great part by exposure to images, often mass-mediated photos. The exhibition also called attention, as does María’s Great Expedition, to the ways “national” culture can originate outside geopolitical boundaries and through the process of migration.

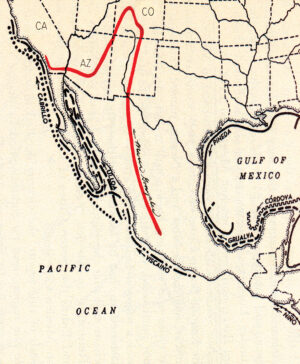

Christina Fernandez, Composite Map from María’s Great Expedition, 1996, inkjet print (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles) © Christina Fernandez

The first image presented in María’s Great Expedition is a map that shows Mexico and the U.S. Southwest. We see the political contours of Mexico and U.S. states, various bodies of water, and land and sea routes. Maps are another key component for building national identity. Though they appear to be the product of a scientific method, maps also tell stories and make claims about resources, inhabitants, and domains. Maps are forms of representation that are not too different from a photograph. The lines and dashes and dots on the page make a claim of relation to the earth; we know that such markings don’t appear on the ground when we cross between Ciudad Juárez and El Paso. Whoever draws up a map or takes a picture, especially one that circulates widely, possesses influence and even power.

Fernandez harnesses this authority to tell a couple of different stories. Her map is a composite one, layering information from various points of view and priorities. These range from major world historical processes—the “exploration” and eventual colonization and settlement by Europeans—to smaller-scale ones, like María’s migration from Morelia to Southern California.

In order to draw attention to María’s trajectory, Fernandez uses a red line that sweeps up from central Mexico, into New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and California. The line can be interpreted as a laceration or scar, recognizing María’s trailblazing and the violence and injustice she encountered along the way. It is more akin to an ocean or mountain ridge, which rarely conforms to political boundaries. We are also reminded that borders that appear so permanent and impenetrable may be relatively recent and contested.

While the “Great” in María’s Great Expedition points to an epic, it can also have a parodic meaning. Expeditions are trips of national import, often for geographic surveys and scientific research. Without discounting the purposefulness of María’s journey—to seek a better life—Fernandez also called attention to the ways narratives of “exploration” and “discovery” often hide the violence of colonization and war. The map in María’s Great Expedition invites the audience to follow María on this journey but also aids in our own “discovery” of the myths of the American West and American Art. We can also follow Fernandez on her embodied exploration of her ancestor through photography.

Christina Fernandez, 1927, Going Back to Morelia; 1930, Transporting Produce, Outskirts of Phoenix, Arizona; and 1945, Aliso Village, Boyle Heights, California, all from María’s Great Expedition, 1995–96, gelatin silver prints (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles) © Christina Fernandez

Snapshots of gender, labor, and class

Fernandez’s installation centers María not only as a woman but as a single mother and head of household. In this way, Fernandez draws attention not only to issues of gender but also labor and class in her interweaving of familial and national narrative. María defied social norms, leaving her husband while pregnant. In three of the photographs, we see her supporting herself and her three children by working various jobs: a housecleaner, a migrant farmer, and a sharecropper, among others.

Fernandez’s photos render this experience, largely invisible to official histories and mass media, visible. That she chooses self-portraiture is significant. Fernandez joins a coterie of women artists in the U.S., especially women of color—including Eleanor Antin, Ana Mendieta, Cindy Sherman, and Carrie Mae Weems—who have used this genre for the purposes of combatting sexist and racist mainstream representation and becoming stewards of their own and their community’s public image through self-fashioning.

Christina Fernandez, 1930, Transporting Produce, Outskirts of Phoenix, Arizona, from María’s Great Expedition, 1995, gelatin silver print (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles) © Christina Fernandez

Fernandez also engages with the history of photography to craft her narrative. For the installation’s fourth photograph, set in Phoenix, Arizona in 1930, Fernandez depicts herself packing up fruits and vegetables to take to market. She loads the heavy wood crates into her car alone. Absorbed in her work, her gaze does not acknowledge the camera. The subject and composition of this photo recalls images produced under the auspices of the U.S. Farm Security Administration (FSA) during the Great Depression starting in the 1930s. The agency commissioned photographers—Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Ben Shahn, Jack Delano, and Gordon Parks, among others—to document the need for and benefits of government aid during the economic crisis, including sharecroppers like María. One of the most iconic images from this project, reproduced widely, was a photo known as Migrant Mother by Lange. It aroused compassion in audiences through its seemingly unvarnished presentation of the suffering of a woman and her children. In adopting Lange’s on-the-spot, no artifice aesthetic, Fernandez makes a case for María as part of an official and iconic repertoire of national imagery.

At the same time, Fernandez reminded audiences of the constructed-ness of such imagery. Though the photographs in María’s Great Expedition depict various points in María’s life they do not aim for total historical accuracy. There are items visible, intentionally included by Fernandez, that take the audience out of the time period of the photo. For example, the artist wears a fanny pack in a 1919 portrait set in Colorado, where María boarded miners against a backdrop of police violence toward labor organizing. However, in being brought back to the time and place of our viewership, we are also presented the opportunity to think about the present-day experience of recent immigrants to the U.S. and working-class culture, where fanny packs are used to keep money and other valuables close to bodies and safe.

Christina Fernandez, 1950, San Diego, California, from María’s Great Expedition, 1995, chromogenic print (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles) © Christina Fernandez

Not an End

For the installation’s final photograph, María stands at a stove, having heated water in a saucepan for a cup of coffee or tea. She wears a knit sweater instead of a rebozo. In this episode, she looks not out beyond the frame but returns the gaze of the camera and the photo’s beholder. With her hand occupied, she holds a newspaper circular for the 99 Cents Only store in between her arm and torso, signaling mundane concerns and thrift. A young woman is now an abuela. Some of the photo’s elements, though, hint at a world beyond the kitchen and a challenging past: the expanse of green-painted wall, decorative plates with pastoral scenes, and a devotional card depicting the Crucifixion. The year is 1950, according to the caption, and María is in San Diego. She is not in good health and has come to live in California with family. María passes in 1952.

While certainly part of the narrative Fernandez presents is the strength and resilience of one person, another story, perhaps a lesson to take away from this work, is that we can see ourselves in each other and in History. Journeys, such as María’s, are bigger than just one person. They remind us that progress is not necessarily linear or orderly, and we should question whether what we are told is natural or just the way things are. This is an inheritance that endows future generations with the right to look forward and the responsibility to remember the sacrifices and successes of ancestors and those in their position. Interacting with Fernandez’s María’s Great Expedition is an experience in this task.

This essay is part of Smarthistory’s Latinx Futures project and was made possible thanks to support from the Terra Foundation for American Art.