Douglas Coupland, Terry Fox Memorial, 2011, bronze and mixed media, dimensions variable, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada (photo: BC Place)

In the shadow of BC Place Stadium in Vancouver, passers-by encounter a line of four bronze statues of a young man running on a prosthetic leg. This memorial commemorates Canadian icon Terry Fox. Each of the four figures is a slight variant on the previous pose, and each grows from life-size to twice that. Spaced equally about half a meter apart, the statues are installed by a simulated highway marked out in darker paving stones. The smoothly finished surfaces of the bronzes display a traditional greenish-brown patina. With muscles tensed, foreheads wrinkled, and determined—even pained—facial expressions suggesting Fox’s struggle and determination. Realistic and dynamic, the bronze figures invite visitors to run beside them by being situated at ground level. At the front of the plaza, the largest image of Fox—symbolically heroic in scale—stands directly on his prosthesis with his left biological leg lifted off the ground. He raises his right arm in a welcoming wave, while his left hand is clenched in a fist—encouraging viewers to confront the magnitude of his accomplishment and legacy.

Terry Fox running in his Marathon of Hope, May 25, 1980 (photo: The Terry Fox Foundation)

Marathon of Hope

In 1980 the young Canadian athlete Terry Fox, who had grown up in British Columbia and had lost his right leg to cancer, embarked on an ambitious cross-country run using a prosthetic leg. His journey, known as the Marathon of Hope, was intended to raise funds and awareness for cancer research. The run began on April 12, 1980, in St. John’s, Newfoundland, and was intended to conclude in Victoria, British Columbia. As Fox made his way from town to town across Canada, his fame grew exponentially. He set himself a grueling 26 mile daily regime, eventually covering over 3,339 miles in 143 days. Having completed half of his projected journey, Fox ended his run near Thunder Bay, Ontario, on September 1. He died the following year at the age of 22.

In a letter to the Canadian Cancer Society (October 15, 1979), Fox explained why he felt compelled to do the run:

The night before my amputation, my former basketball coach brought me a magazine with an article on an amputee who ran in the New York Marathon. It was then I decided to meet this new challenge head on and not only overcome my disability, but conquer it in such a way that I could never look back and say it disabled me.[1]

The artist Douglas Coupland has noted just how profound Fox’s action was in the 1970s:

It’s important to remember that in 1979 people with disabilities . . . didn’t participate in the everyday world the way they do now. For someone with one leg to enter a race of this length was quite shocking.[2]

Terry Fox immediately became a Canadian cultural icon, and starting with a statue in Thunder Bay, public monuments to his memory have appeared in cities across Canada.

A different kind of memorial

Douglas Coupland, Terry Fox Memorial, 2011, bronze and mixed media, dimensions variable, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada (photo: Ross, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Three decades after the Marathon of Hope, Vancouver-based novelist, designer, and visual artist Douglas Coupland was commissioned by the BC Pavilion Corporation to design a new public memorial to Terry Fox for BC Place Stadium in Vancouver. In this busy location, adjacent to a popular sports venue, the monument would be accessible to a large and diverse audience. Working with sculptor Stephen Harman, Coupland’s guiding principle was public legibility—the importance of Fox’s story had to be made clear to passers-by. The result is a memorial that is relatively conventional in terms of its material—bronze—and in its straightforward representational approach. In this sense it matches expectations for public statues and invites a broad cross-section of the public to remember Terry Fox. In fact, the choice of materials was largely to ensure the work’s permanence: as the artist stated at the 2011 unveiling, he wanted people living a thousand years from now to understand Fox’s achievement.

Coupland used photographs and videos for reference, specifically a series of sequential photographs that illustrated the four movements that made up Fox’s running style. This distinctive hop-and-skip gait became a symbol of the Marathon of Hope in the minds of many Canadians. Fox discussed his unique stride: “Some people can’t figure out what I’m doing. It’s not a walk-hop, it’s not a trot, it’s running, or as close as I can get to running, and it’s harder than doing it on two legs.” [3] By separating out the different postures of Fox’s gait and by multiplying and sequentially enlarging his image, Coupland emphasized a prolonged process of pain, struggle, and courage, saying: “You realized through the run that there wasn’t one single step he took where his body wasn’t in some kind of pain, large or small. . . . Boy, it really puts you in your place.” [4] At the same time, Coupland intended the growing height of each figure to symbolize the increasing fame and importance of the subject as the Marathon of Hope progressed.

Coupland made no attempt to beautify or idealize Fox’s proportions, facial features, or pose. Instead, he invites viewers to embrace a new set of standards regarding diverse representations of the human body in public art. It is notable that the fourth and largest of the four statues depicts Fox standing erect and determined on his prosthesis. All other earlier Fox monuments across Canada—notably those in Thunder Bay, Ottawa, Burnaby, and Victoria—show him leaning forward to take his weight on his biological leg, which serves to move his body toward his goal. In Coupland’s work, the prosthesis has become a full part of Terry, and his “disability” is not hidden but brought forward and validated.

Left: Edwin Railton, E.H. Bailey, and Sir Edwin Landseer, Nelson’s Column, 1840–43, granite and bronze, 169 feet 3 inches high, Trafalgar Square, London (photo: Elliott Brown, CC BY 2.0); right: Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, Peter Stuyvesant, 1941, granite and bronze, 8 feet high (photo: Wally Gobetz, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

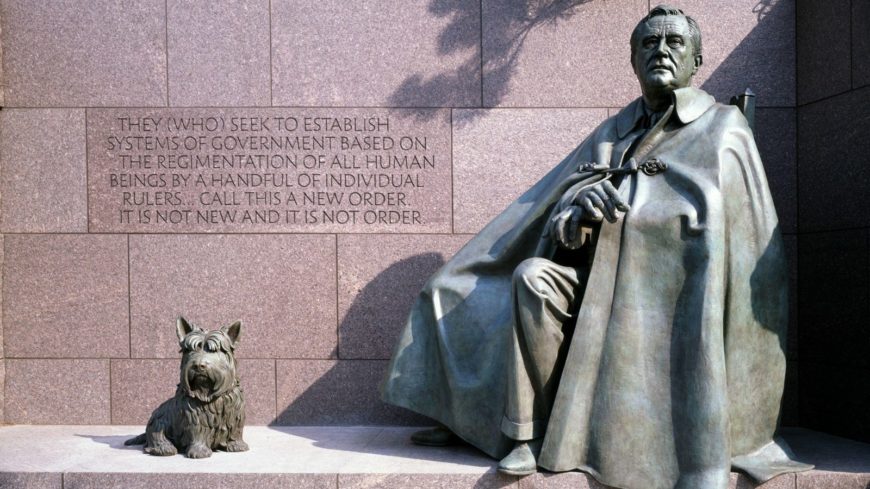

There are several famous examples of disabled figures in earlier Western public statuary—Edward Baily’s Lord Nelson in London’s Trafalgar Square, or Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s Governor Peter Stuyvesant in New York. Both historical figures had missing limbs, yet their bronze representations follow traditional nineteenth-century formulas for heroic monuments. They are raised above the viewer on tall pedestals, and their disabilities—if not totally concealed—are minimized.

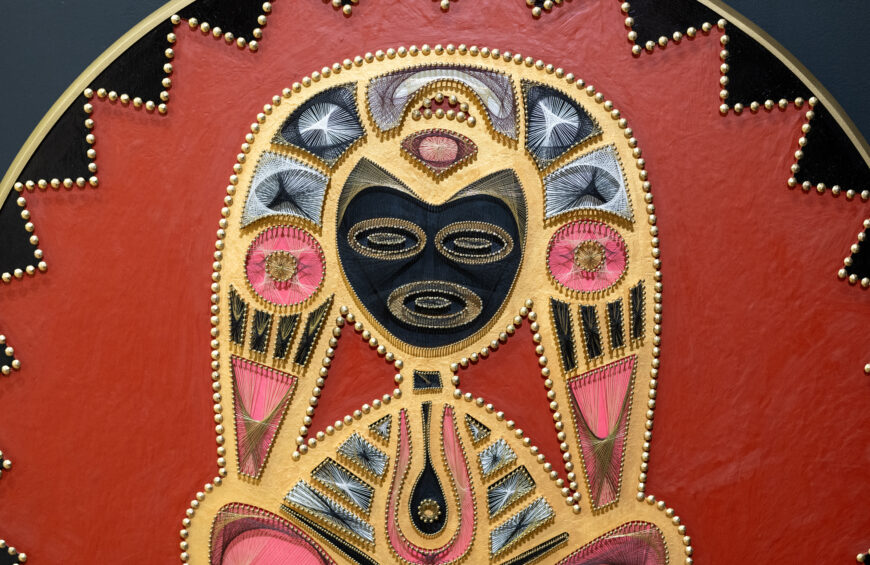

Neil Estern, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Fala, 1997, at the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, Washington, D.C. (Carol M. Highsmith, Library of Congress)

More recently, an over-life size statue of President Franklin D. Roosevelt by artist Neil Estern caused some debate when unveiled at the new FDR Memorial in Washington, D.C. in 1997. Controversy arose when historians and disability-rights advocates noted that the president’s disability and wheelchair had been concealed underneath a large cloak, following the precedent of public images of FDR made during his lifetime. (In 2001, a new life-size statue of FDR was added to the Memorial; following recommendations that the president’s wheelchair be shown openly in the interests of historical accuracy and the need to inspire people in comparable circumstances, artist Bob Graham depicted FDR sitting in a wheelchair similar to the one he actually used.)

Interestingly, it was in the same year that Bill Koochin’s stone statue of Canadian athlete Rick Hansen in his wheelchair was installed in Vancouver without incident. In this case, however, Hansen’s achievement was clearly linked to his disability, and images of him engaging in athletic activities in his wheelchair were widely known. This new kind of frank realism in public monuments invites viewers to interact with a new set of aesthetic and ethical ideals. As Susan Wendell reminds us in her book, The Rejected Body, “the lack of realistic cultural representations of experiences of disability not only contributes to the ‘Otherness’ of people with disabilities by encouraging the assumption that their lives are inconceivable to non-disabled people but also increases non-disabled people’s fear of disability by suppressing knowledge of how people live with disabilities.” [5] Marc Quinn’s landmark representation of artist Alison Lapper also comes to mind, and in this context Coupland’s monument in Vancouver appears as the culmination of a long series of public works that represent differently abled figures in a heroic guise.

Douglas Coupland, Terry Fox Memorial (detail from behind), 2011, bronze and mixed media, dimensions variable, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada (photo: Karen Lee Photography, CC BY-SA 2.0)

A participatory monument in a digital age

Coupland’s monument replaced an earlier Fox monument on the site, created in 1984 by architect Franklin Allen and artist Ian Bateson. This had taken the form of a postmodern, Roman-inspired triumphal arch, topped by stylized lions—traditional Western symbols of strength and heroism—on each corner of the roof. This design met with an immediate and ongoing negative reaction from the public, partly because many felt that it did not reflect Fox’s humble personality. Most importantly, it initially contained no actual representation of Fox (at a later date a larger-than-life etching of the athlete, as well as a map showing his journey across Canada, were added by artist Ian Bateson.) But Coupland’s new monument introduces a powerfully immersive approach to its subject that differs from all the earlier—and perhaps more traditional—monuments to Fox.

Coupland invites the viewer to recreate the spirit and energy of Fox’s run by providing an experiential and participatory component. This typifies a trend in many contemporary monuments that aim to actively engage visitors in a physical interaction rather than encourage passive contemplation. In this case, visitors can run beside the statues of Fox, installed at ground level, on the simulated highway to one side. The receding lines of the highway, in combination with the differing heights of the figures, create a forced perspective that suggests Fox moving toward us from a distant point of origin. Approaching the monument from across the street, visitors may feel that they are witnessing a segment of Fox’s run all over again. In an interview with a local newspaper, Coupland also suggested that he “wanted to create something that people could interact with on a digital level.” [6] He demonstrated his intention by picking up an iPhone, suggesting that visitors could create their own photographic animations of Terry’s run. Coupland’s monument, with its naturalistic approach, participatory goals, and outreach to our own digital age is intended to inspire current and future generations with Terry Fox’s belief that “anything’s possible if you try; dreams are made possible if you try.” [7]