Luo Zhongli, Father, oil on canvas, 1980, 215 x 150 cm (National Art Museum, Beijing, China)

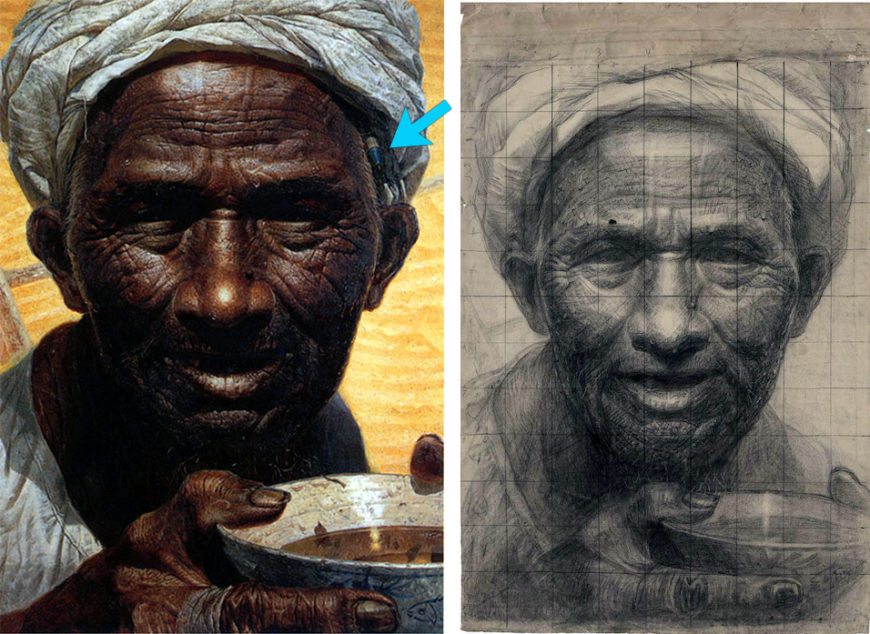

When Luo Zhongli’s oil painting, Father, was first exhibited at the Second National Youth Exhibition in 1981 in China’s capital, Beijing, visitors were astonished by what they saw. It was not necessarily the subject matter, composition, or colors that drew them in. Rather, it was the raw truthfulness with which Luo depicted his subject. Originally titled “My Father,” this painting is based on sketches he made of a man whose job was to guard a local manure pit in the remote Daba Mountains. This artwork elicited strong reactions among the Chinese public and remains one of the most revered paintings from this period in China’s history.

A rural inhabitant

The subject matter of a rural inhabitant would not have been new or shocking to a Chinese audience at the time. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, the “peasant” was upheld as one of the three “heroes” of Communist leader Mao Zedong’s socialist revolution, alongside soldiers and workers. In fact, it was only through the support of China’s vast peasantry that the communists were able to consolidate power in 1949 after many years of civil war.

Lasting from 1966–1976, China’s Cultural Revolution was Communist leader Mao’s last push to maintain his power over the nation. Marked by anti-intellectualism, cultural and economic isolation, and totalitarianism, it was one of the most oppressive and violent periods in China’s modern history. In 1968, in an attempt to diffuse the violent uprisings of the student militants known as the Red Guard, Mao declared that the youth of China’s cities should move to the countryside to be re-educated by the rural peasantry. Luo Zhongli, after graduating from the Sichuan Academy preparatory middle school in Chongqing in 1968, was one of millions impacted by this policy. He lived for ten years in the rural Daba mountain region on the border between Sichuan and Shaanxi provinces, where he encountered the man who would later become the subject of his most celebrated painting.

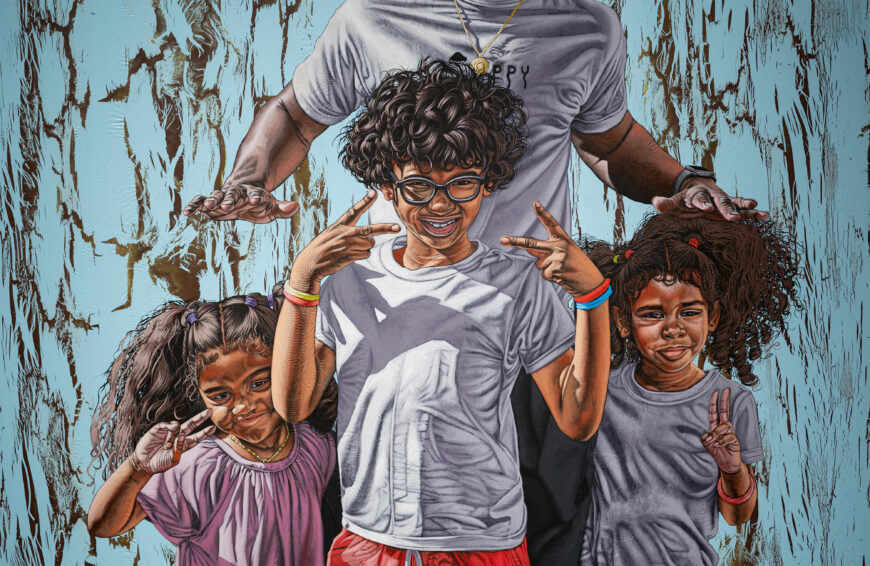

Examples of propaganda posters of the 20th century featuring idealized peasants: left: Zhang Yuqing, “The Future of the Rural Village,” October 1958, 53.5 x 76.5 cm (private collection); right: Revolutionary Group of the Second Liaison office of the Fifth Battalion of the Shanghai Cultural System, “Prepare for Struggle, Prepare for Famine, For the People,” 1970, 53 x 77 cm (IISH collection)

Depicted as happy, strong, and healthy, the idealized image of the peasant came to represent the success of the Communist Party in the propaganda paintings, posters, and murals of the time. Most of the prints and posters that were widely disseminated were originally based on oil paintings. In Zhang Yuqing’s poster “The Future of the Rural Village,” for example, the well-dressed and hearty peasants work happily together in a village containing state of the art agricultural machinery, a streetlight, and a telephone, all symbols of a wealthy, technologically advanced country. Unfortunately, the artworks did not reflect the harsh reality that many rural inhabitants endured as a result of poverty, famine, and poor infrastructural planning under Mao’s leadership. The Cultural Revolution came to an end after Mao’s death in 1976. After the implementation of new policies which opened China’s economy to the rest of the world in 1978, Chinese people began to reflect upon the reality and legacy of Mao’s revolution. Luo’s large-scale oil painting Father (made in 1980) is representative of this larger trend of historical reassessment.

Still, as Luo once said “The image of this old peasant actually is the summary of the images of so many peasants in my mind.” In fact, he never knew the man’s name that he painted. There is an interesting tension in the specificity of the photorealist style and the fact that this figure still stands as a symbol for “peasants” in general. It demonstrates how at this time in Chinese history, the “peasant” still held a strong symbolic meaning that was directly related to China’s process of modernization. The jury of the exhibition actually changed the name from “My Father” to “Father,” which pushes the symbolic function of the painting even further.

Photo-realistic

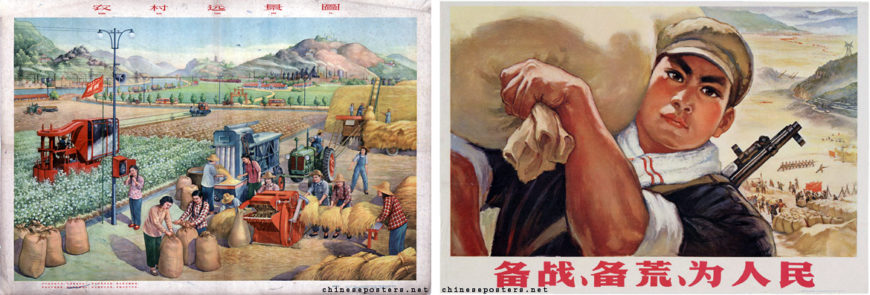

Chuck Close, Mark, 1978–79, acrylic on gessoed canvas, 274.3 x 213.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

After 1978, as part of China’s opening its doors to the rest of the world, Chinese publishing houses released translations of foreign literature and philosophy, and art journals began to print reproductions of foreign artworks, initiating a period often referred to as “Cultural Fever.” Although Luo had never seen an actual reproduction of any of Chuck Close’s work, he was inspired to take a similar approach when painting Father as the American artist after reading a vivid description of his photorealistic style by a Japanese author. [1]

For a Chinese viewer in 1980 accustomed to the propaganda of the Mao period, the lack of triumphant heroism in Father — that had previously been required in representing a peasant — would have been shocking. Instead, he focuses in the most direct way on the painful labor this man, and those he represents, has endured. The composition is almost entirely filled by the man’s face, which is friendly, but at the same time confronts the viewer directly, returning our gaze, implicating us. Both face and hands are covered in fine and deep wrinkles, a single tooth pokes jaggedly out of the right side of his mouth, his fingernails are filthy, sweat drips from his forehead, brow, and nose, one finger is wrapped with a thin bandage, and the bowl of tea he holds is cracked. He stares straight out at the viewer, squinting in the harsh sunlight that is reflected on his forehead, nose, and lower lip.

Unlike the Revolutionary Realism of Maoist propaganda, a style which Luo mastered during the Cultural Revolution, this painting highlights the harmful effects of years of working in the hot sun, revealing a truth that had been unspoken during the previous decades. This, combined with the man’s guileless gaze, inspires compassion and reverence for the millions like him that gave so much of their lives and health attempting to fulfill Mao’s utopian dreams.

Wang Guodong, Portrait of Mao above Tiananmen Gate, 1964, 20 x 15 feet (6.1 x 4.6 m)(photo: Nicor, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Monumental in size

Viewers in front of Luo Zhongli, Father, oil on canvas, 1980, 215 x 150 cm (National Art Museum, Beijing, China)

One reason this painting was so moving to viewers was its monumental size, measuring about 215 x 150 cm. Such a large scale had previously been reserved for portraits of powerful politicians, and before that, emperors, ancestors, and literati officials. In fact, Father’s large scale and composition is reminiscent of the most famous Chinese portrait at the time: the portrait of Mao Zedong by artist Wang Guodong, a version of which continues to hang above Tiananmen Gate watching over Tiananmen Square in Beijing. Some were so moved by the painting that they even suggested that Father should replace Mao’s portrait.

Although the audience was urban-based, many had had experiences similar to Luo’s in which they were sent to the countryside to learn from the rural peasantry. Others still traveled from the countryside and smaller towns and villages to see the exhibition. This connection with the rural countryside held by so many undoubtedly enhanced the feeling of identification with the portrait. Luo has said:

Our country is a country of peasants. But those who speak for them are few and those who speak the truth are even fewer. They are our father and mother who provide us with clothing and food, they are the veritable masters of our country. [2]

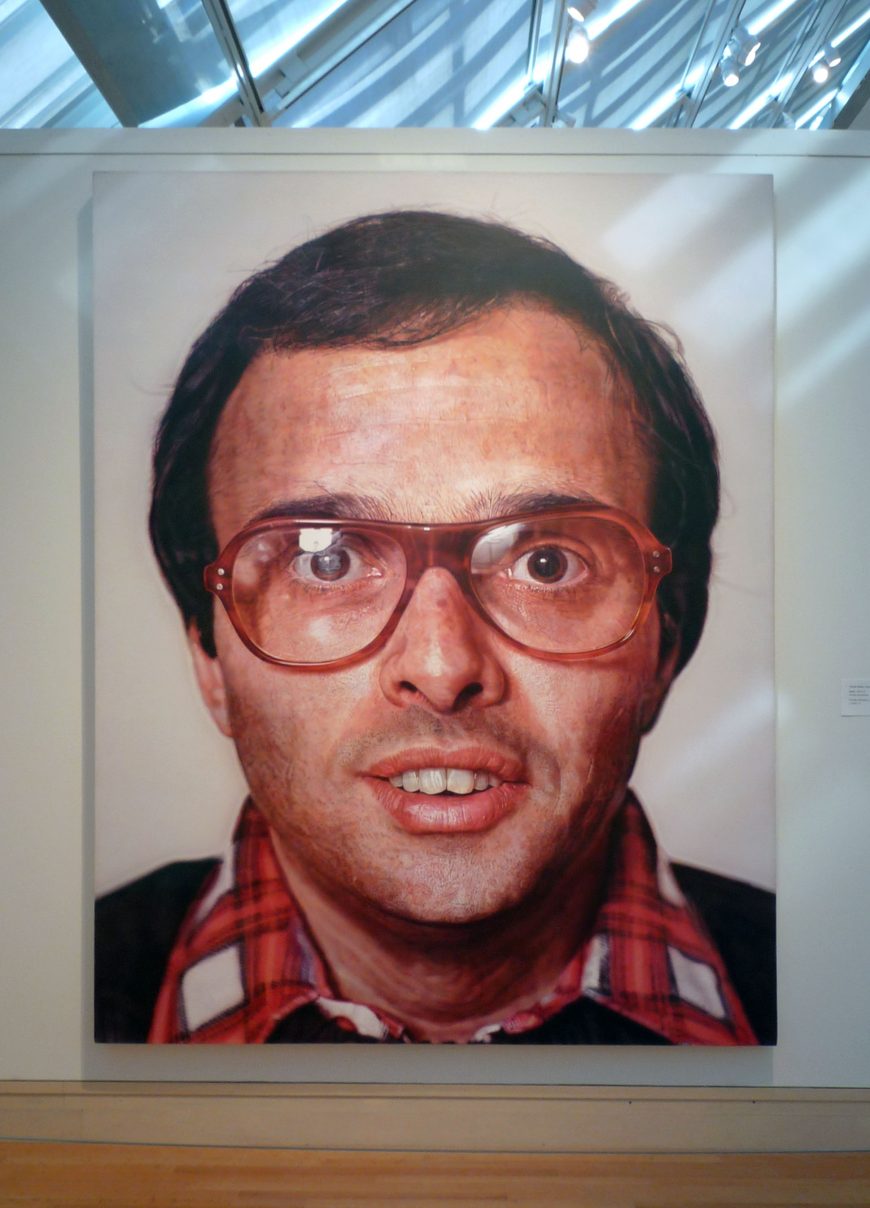

Left: location of the pen in Luo Zhongli, Father, oil on canvas, 1980, 215 x 150 cm (National Art Museum, Beijing, China); right: a draft by Luo Zhongli for Father in which the pen is not there

What’s with that pen?

One detail that strikes many viewers as out of place within the composition is the ball point pen resting behind the man’s left ear. It is important to note that the exhibition where this work was first displayed was officially sponsored by the central government and therefore had a political agenda to promote the positive elements of Chinese society. It was within this context that the chairman of the Sichuan Artists Association, Li Shaoyan, insisted that Luo add the ballpoint pen to the composition for fear it would not be accepted into the exhibition without it. The pen was pivotal in expressing that this peasant was modern and educated, representative of China’s hopeful future, rather than being seen as a direct attack on the policies of the Chinese Communist Party, who continued to hold power after Mao’s death and remain in power today.

Ongoing relevance

Throughout the 1990s, Chinese economic and political policies began to favor urban development over rural stability. In the last 30 years, millions of rural inhabitants, unable to make a living in their hometowns and villages, have been forced to work as migrant laborers in Chinese cities along the East coast, often lacking economic and legal stability. While in recent years the government has attempted to improve China’s rural economy, the rural inhabitant remains one of the most marginalized within the current system of global capitalism. It is perhaps for this reason that Luo Zhongli’s painting continues to resonate both in China and around the world, decades after it was first painted.