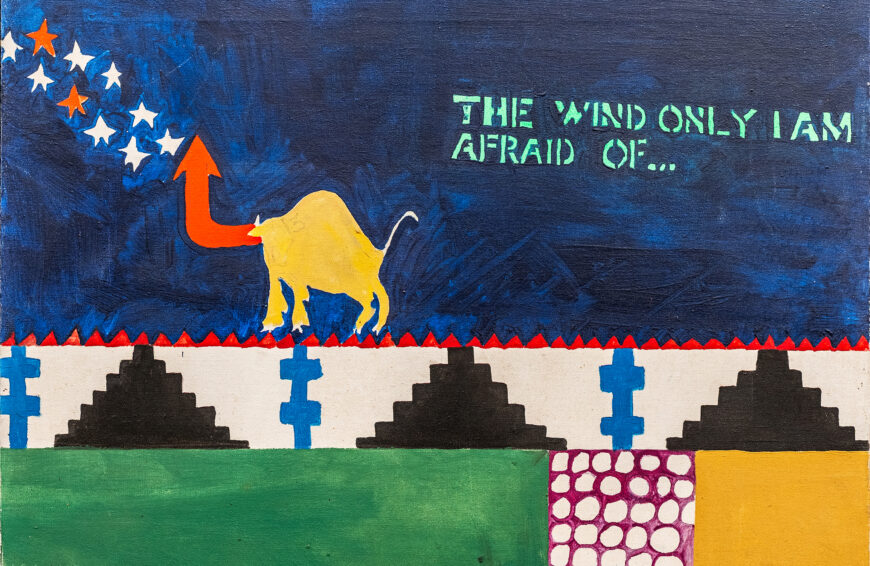

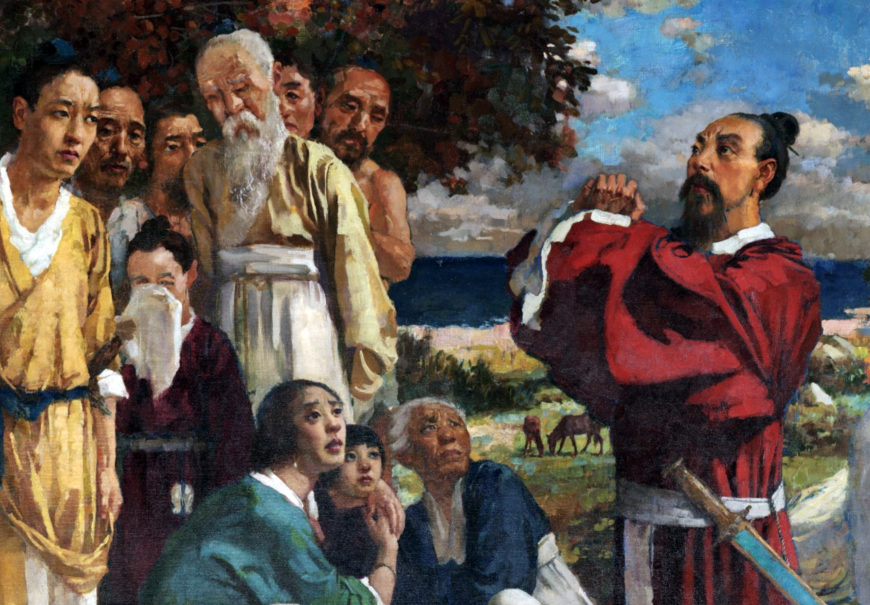

Xu Beihong, Tian Heng and His Five Hundred Followers, 1928–30, oil on canvas, 197 x 349 cm (Xu Beihong Memorial Museum, Beijing)

Onlookers gaze at a red-robed figure standing on a beach with his hands clasped together, his white horse shifting its weight behind him. Both young and old, common and noble, gather to witness the scene, their faces and gestures displaying a mixture of emotions. In this captivating oil painting, Xu Beihong recounts an ancient legend, Tian Heng and His Five Hundred Followers, by picturing the heroic 3rd-century B.C.E. prince Tian Heng at a pivotal moment. Defeated in war, Tian Heng fled to an island and was called upon by the emperor to surrender. Tian Heng surrendered but killed himself on his way back to the capital—a fate he announces with great conviction in Xu’s painting. Upon hearing of his fate, five hundred followers killed themselves out of loyalty to the hero and his cause. Xu’s mastery of color, light and shadow, and figural expression in this carefully composed work underscored the patriotic interests of the artist and his desire to reform Chinese painting in the modern era.

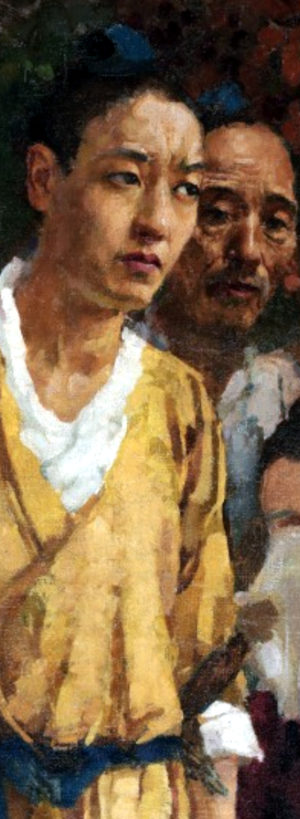

Tian Heng in red on the right, with some of the crowd reacting to him. The artist is on the far left in gold. Xu Beihong, Tian Heng and His Five Hundred Followers (detail), 1928–30, oil on canvas, 197 x 349 cm (Xu Beihong Memorial Museum, Beijing)

History painting for modern China

Although the legend of Tian Heng took place two thousand years earlier in China’s Han dynasty, this historical event offered an allegory for modern viewers—ostensibly to inspire patriotism and self-sacrifice in light of the rise of Japanese imperialism. Outraged by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, which awarded Japanese-occupied territory in Shandong province to Germany, Chinese demonstrated in Beijing—marking the start of the May Fourth Movement, which deeply moved Xu and his contemporaries. This nationalistic movement aimed to restore China’s position among world powers, principally through creating a new culture inspired by Western notions of science and democracy, but also with the hope of thwarting Japanese aggression.

Figures rolling up their sleeves, with one who grasps a sword. Xu Beihong, Tian Heng and His Five Hundred Followers (detail), 1928–30, oil on canvas, 197 x 349 cm (Xu Beihong Memorial Museum, Beijing)

Xu Beihong placed himself in his painting of Tian Heng and His Five Hundred Followers (detail), 1928–30

Using both colors and ink, Xu portrayed Tian Heng in velvety red robes as a hero standing on the beach of the island, while the facial expressions and gestures of the crowd suggest predictable expressions of awe, despair, and loyalty. Some appear to roll up their sleeves and grasp their swords in readiness, while others cling to one another in gestures of protection. The artist pictured himself at the center of the crowd, illuminated in a ray of light and wearing gold robes, as if expressing his personal admiration of Tian Heng’s decision even though it took place long before. With furrowed brows and the hilt of his sword tucked beneath his arm, Xu pictured himself gazing solemnly at Tian Heng.

Through works like Tian Heng and His Five Hundred Followers, Xu advocated for a complete reform of Chinese painting by incorporating observation of the natural world and Western techniques. He first traveled to view art in Japan, and later studied abroad in Paris during the 1920s, where he studied drawing from life and copied works by artists like Eugène Delacroix and Rembrandt van Rijn in the Louvre. Perhaps those works informed his lavish use of jewel tones of blues, crimson, and gold as well as dramatic light and shadow in the legend of Tian Heng.

Rather than look to more recent works by French modernists such as Paul Cézanne or Henri Matisse, Xu continued to favor earlier European oil paintings in the conventional Salon style of the late nineteenth century—such as large history paintings made for government-sponsored Salons where painters made bids to display their works, many of which exemplified interests in realism and middle-class subject matter.

Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, 3.3 x 4.25 m, painted in Rome, exhibited at the salon of 1785 (Musée du Louvre; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

For instance Tian Heng, which is massive in scale, recalls works on a large scale made for the Salon like Jacques Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii that uses Greco-Roman themes to portray self-sacrificial loyalty as a civic virtue. Immersed in bohemian Paris, Xu also may have drawn upon works such as Picasso’s Boy Leading a Horse; Picasso was himself, of course, interested in neoclassical art.

Although Xu exhibited his oil paintings in the official Salon in Paris and participated in other exhibitions throughout Europe, he painted Tian Heng after his return to China in 1927; he started the painting in Shanghai in 1928 and completed it in Nanjing in 1930. There, he was appointed by the Minister of Education Cai Yuanpei to lead the newly established National Central University first in Nanjing and later in Chongqing, after war broke out in 1937. Japan launched a full-scale invasion in Beijing, followed by Shanghai and Nanjing, where tens of thousands perished in the six weeks following Japan’s invasion known as the “Nanjing Massacre.” Having fled to Chongqing, Xu continued to teach drawing and formal observation as the basis for what he viewed as “realistic” oil painting, while also returning to Chinese ink painting.

Xu Beihong and the New Culture Movement

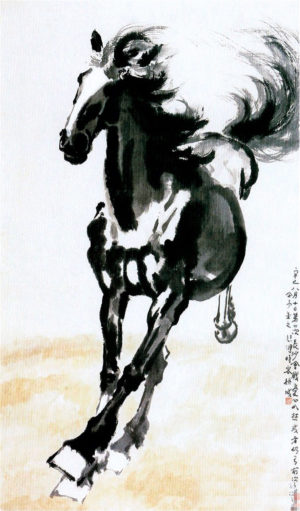

Xu Beihong, Galloping Horse, 1941, ink and color on paper (hanging scroll), 130 x 76 cm (Xu Beihong Memorial Museum)

Moved by the progressive goals of the New Culture Movement, Xu became a prominent voice in contemporary debates about Chinese art in modern society. Beginning with an article published by the revolutionary Chen Duxiu in the radical journal New Youth (Xin qingnian 新青年) in 1915, the New Culture Movement aimed to rally China’s youth toward social progress through Western ideas of science and democracy, and urged a move away from classical Confucian thought. Xu and other artists who had visited Japan and Europe, trained in international art schools and taught in newly established Chinese universities, responded to this charge in a variety of ways—some embraced European modernism (like Liu Haisu and Lin Fengmian), while others (like Xu and the Gao brothers of the Lingnan school) experimented with Chinese subjects and media along with European techniques.

The wide range of works by Xu exemplifies his goal to advance Chinese art without abandoning traditional subjects and media. His paintings may not have been especially successful in their aesthetic qualities, but Xu’s life and works had great theoretical consequences in his time. For instance, although his study of European techniques informed Xu’s portrayal of the legend of Tian Heng, poised beside his valiant white horse, Xu also rendered the horse as a subject in the traditional medium of Chinese ink. In Galloping Horse, Xu captured the realistic movement and the innate spirit of the horse in only a few, quick strokes. The painting offers an approach seemingly at odds with the measured techniques of European academic art, but one that is entirely in line with traditional Chinese painting and its focus on brushwork, which is often referred to as an “art of the line.”

Attributed to Han Gan, Night-Shining White, c. 750, ink and color on paper (handscroll), China, 30.8 x 33.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The contrast between Tian Heng and Galloping Horse further reveals that Xu was not only concerned with formal observations—whether of colors and volume in Tian Heng, or lines and movement in Galloping Horse—but also Chinese themes of patriotism and noble behavior in his subjects. Throughout the history of Chinese art, horses have been regarded as celestial steeds that are likened to mythical dragons and used to symbolize talented officials—such as we see in Night-Shining White from the 8th century.

In the absence of emperors and officials in Republican China, Xu extended these legendary traits to the heroism of Chinese soldiers. He used these images to raise awareness for the patriotic cause of Chinese sovereignty, organizing exhibitions abroad of his ink paintings to raise money for his country amid the threat of Japanese imperialism.

Reform in many forms

In picturing a Chinese legend in the medium and technique of a European history painting, Tian Heng and His Five Hundred Followers illuminates the international outlook and activism of artists in the Republican era. Xu’s efforts to reform Chinese painting took many forms, whether oil or ink painting, yet nonetheless emphasized close visual observation and patriotic themes. For Xu and many of his colleagues, the reform of Chinese painting offered a way to advance China’s position in the modern world.