In 1905, the celebrated Indian artist Abanindranath Tagore debuted his painting of Bharat Mata. Made from gouache, Tagore’s painting is one of the earliest renderings of the idea of “Bharat Mata,” or “Mother India,” as a political icon. The work centers on a lone female figure draped in saffron-colored robes, who stands amid a glowing landscape where earth and sun entwine in a flash of blended pigment behind her. It is clear that this lone figure is no ordinary woman, but Bharat Mata. Her divine stature is signaled by the double halo that enshrines her head, the aura of light that extends down her legs, her multiple arms, and the line of lotus flowers on the ground beside her feet. She is also identifiable from the blessings that she holds in each of her four hands. Food (shown as grain), clothing (shown as cloth), knowledge (shown as a manuscript), faith (shown as prayer beads)—these are the building blocks and promise of a healthy national future. [1]

Figure holding four blessings (detail), Abanindranath Tagore, Bharat Mata, 1905, gouache, 26.6 x 15.2 cm (Victoria Memorial Hall, Kolkata)

Tagore crafted Bharat Mata amid the fervor of the anti-colonial Swadeshi movement in Bengal, with an awareness that the image would be used to galvanize early support for anti-colonial resistance (direct British rule was imposed on India from 1858–1947, when it became independent). He initially conceived the work as “Banga Mata” or Mother Bengal, modeling the painting on the everyday Bengali woman, perhaps even his own daughter. [2] The painting, however, quickly acquired recognition as Mother India, a wider embodiment of the emerging Indian nation. Bharat Mata was copied by other artists, used on posters in Swadeshi fundraising campaigns, and republished in vernacular media. [3] In 1906, a local magazine reprinted the painting with the label, “The Spirit of the Motherland,” foretelling the prominent place the symbol would come to occupy in the Indian national movement a few years later. [4]

Making past present

Tagore’s Bharat Mata is important both for giving early visual form to this salient political icon and for the ideas the work proffered, on the whole, for the direction of modern art in South Asia. Rising anti-colonial sentiments in the late 19th century had produced a series of debates around the nature and origins of Indian aesthetics. These debates pushed modern artists, like Tagore, in search of new modes of artistic practice that could be harnessed by a burgeoning national polity in South Asia. [5]

In forging this new artistic language, Tagore regularly drew inspiration from the subcontinent’s early artistic heritage. In Bharat Mata, for instance, he compiles the figure’s iconography from visual forms common to South Asian art prior to the 20th century and which hold special significance for several South Asian religions, including Buddhism, Jainism, and Hinduism. More than simply a gesture of cultural renewal amid a period of colonial rule, Tagore’s collected iconography for Bharat Mata asserts the longevity of the subcontinent’s past and heritage through the body of an emerging national icon. It also steeps Bharat Mata in new ideas of Pan-Indian cohesion, befitting an anti-colonial national project in early stages of mobilization.

A recurring form in early South Asian art, the halo was used by Indian artists across the region to imbue figures with divine power and authority. Tagore extends this practice to the figure of Bharat Mata, whose halo is a prominent feature of the composition, formed from a pair of concentric circles that radiate outwards from her body into a golden hue. Bharat Mata’s halo, perhaps foremost, recalls the early iconography of the Buddha in South Asia. As seen in early Buddhist sculpture from Gandhara, the Buddha’s enlightened status is often conveyed through circular rays of light which encircle the Buddha’s head like a crown.

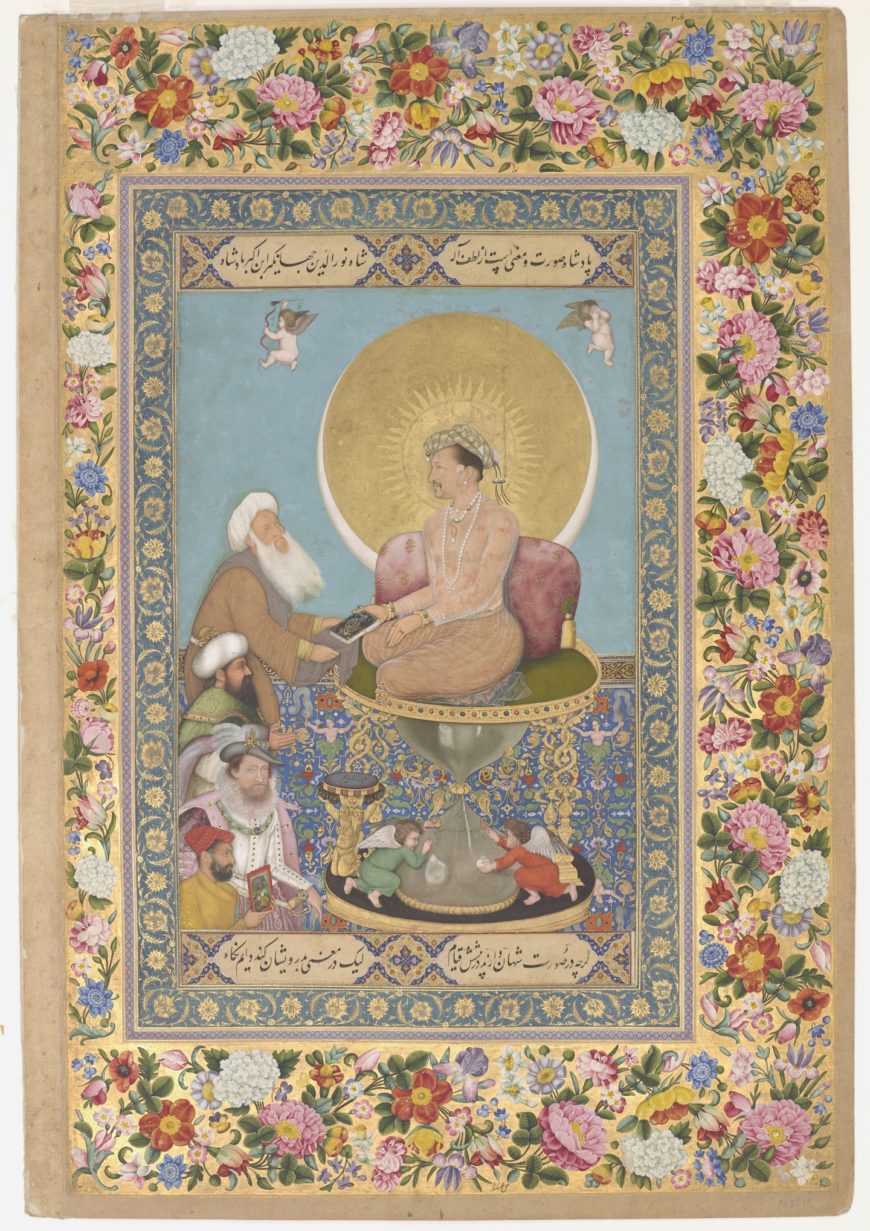

Bichitr, margins by Muhammad Sadiq, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings from the “St. Petersburg Album,” 1615–18, opaque watercolor, gold and ink on paper, 46.9 x 30.7 cm (National Museum of Asian Art, Washington, D.C.)

Bharat Mata’s halo also, however, recalls the conventions of 17th-century Mughal manuscript painting, where the halo was used to visualize new conceptions of divine kingship in South Asia. Tagore’s image, in this regard, is reminiscent of allegorical portraits such as Bichitr’s Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings and Abu’l Hasan’s Jahangir Embracing Shah Abbas. In such paintings, the halo blurs the Mughal emperor Jahangir’s body with key natural elements, such as the sun and moon, to suggest the sovereign’s kinship with nature and, by extension, his authority over his earthly political rivals.

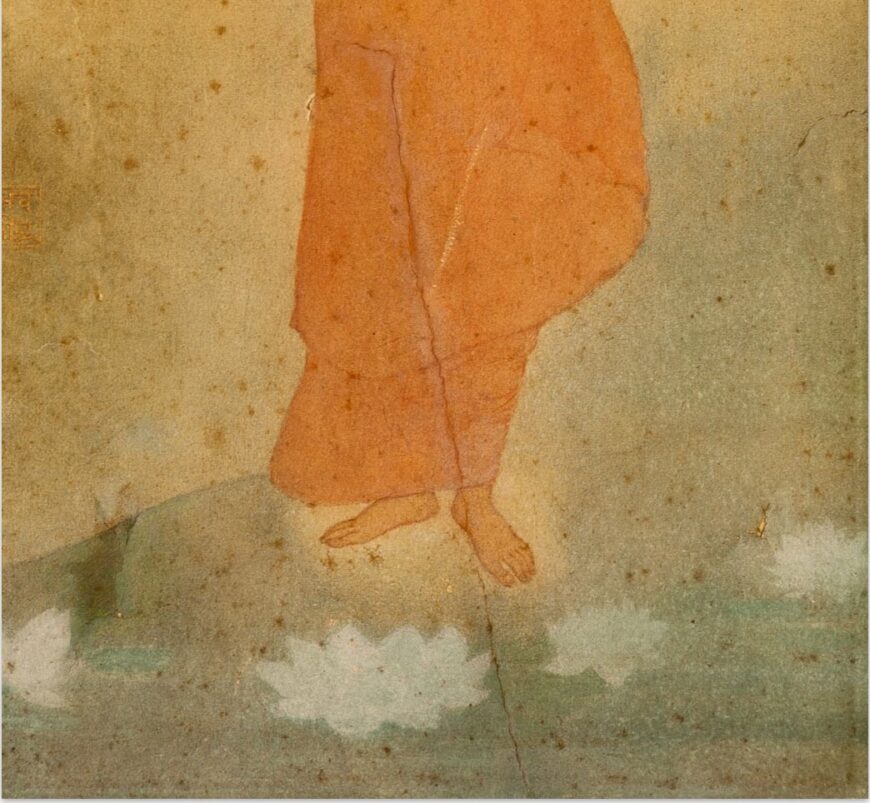

Lotus flowers (detail), Abanindranath Tagore, Bharat Mata, 1905, gouache, 26.6 x 15.2 cm (Victoria Memorial Hall, Kolkata)

The lotus flowers that surround Bharat Mata like a throne place Tagore’s painting in dialogue with other early Buddhist monuments in South Asia, including the Great Stupa at Sanchi. The lotus flower is an important metaphor for the Buddha’s life and teachings, associated with ideas of spiritual purity, enlightenment, and devotion. Such flora is carved in abundance at Sanchi, where it imbues the site’s reliquary architecture and monastic complex with a sacred status becoming of the Buddha and his devotees. In Tagore’s painting, the presence of lotus flowers beneath Bharat Mata’s feet, like her halo, helps to underscore the figure’s ethereal difference and in turn elevate the idea of Indian collectivity. [6]

Durga slays the Buffalo Demon Mahishasura, from the north side of Mahishasuramardini Mandapa, Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu, India, c. 7th century, granite, approximately 2.4 x 4.6 m (photo: © Arathi Menon, all rights reserved)

Bharat Mata’s many arms also potently invoke early depictions of the Hindu goddess Durga. In the Hindu pantheon, Durga is an important consort of Lord Shiva. She is worshipped for her strength and power, as both warrior and primordial mother. [7] In early Hindu reliefs such as Durga Slaying the Buffalo Demon at Mamallapuram, Durga is depicted as the embodiment of the feminine and divine force of shakti. She sits astride her lion, confidently engaged in battle against the forces of evil, with weapons bestowed from the heavens in each of her eight arms. Bharat Mata’s close kinship with such images of Durga lends Tagore’s composition a sense of strength and transcendence, important for a nation in the process of becoming. These iconographic ties also, however, point to the potential limits of Tagore’s Pan-Indian vision, anticipating the role Bharat Mata would later play as a national icon in figuring the Indian nation as predominantly Hindu, to the exclusion of other religious minorities.

Painting a national icon

Setting aside the painting’s iconography, Tagore’s Bharat Mata is also noteworthy for inaugurating the Bengal School of Art, which by the 1940s was celebrated by art critics and leaders within the Indian national movement as a true “national” art form. Pioneered by Tagore in the early 20th century, this new mode of painting was envisioned as an “Indian” counter to the predominance of British academic art in South Asia.

Academic art refers to a style of naturalistic painting and sculpture nurtured by European academies of art in the 19th century and later British art schools in South Asia. It is an artistic approach that prioritizes materials such as oil and canvas, and techniques such as linear perspective, foreshortening, and chiaroscuro to achieve strong illusionistic effects and narrative legibility.

A celebrated example of academic art in South Asia is Raja Ravi Varma’s The Galaxy of Musicians. Commissioned by the Maharaja of Mysore in 1889, the painting brings to life a diverse group of Indian women engaged in a musical performance. The painting is notable for its rich, naturalistic detail and for its allegorical use of the Indian woman to personify the geographic and cultural diversity of the Indian subcontinent.

Raja Ravi Varma, A Galaxy of Musicians, 1889, oil on canvas, 49 x 43 inches (Sri Jayachama Rajendra Art Gallery, Jaganmohan Palace, Mysore, Karnatak)

Tagore’s Bengal School of Art, in contrast with the British academic style, is interested more in harnessing the coloristic and emotive possibilities of regional materials such as tempera and watercolor, which were long central to local forms of South Asian art, including Mughal, Rajput, and Pahari painting. As seen in Bharat Mata, it is a style of painting that forsakes the bold lines, stringent linear perspective, and verisimilitude of academic art in favor of flatter picture surfaces and large swathes of blended color.

This shift in material and technique encouraged Indian artists to use painting to explore the complexities of human interiority and intimacy, with palpable ramifications for an image like Bharat Mata. The Bengal School style, in this regard, not only lends Bharat Mata a new sense of authenticity at a time when the idea of “Indian” art and culture was in flux, but also helps to ground Bharat Mata and, by extension, the idea of the Indian nation, in the realm of the personal and the everyday. In spite of her divine stature, Bharat Mata and her promise of self-sufficiency is made available and accessible to viewers.

Abanindranath Tagore, The Journey’s End, c. 1913, tempera on paper (National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi)

Tagore’s signature “wash technique” is another defining characteristic of the Bengal School approach. This form of loose brushwork, which centers color and mood, grew from Tagore’s interest in Pan-Asianism and his wider experimentation with Mughal manuscripts and Japanese ink painting. [8] In Bharat Mata, this kind of brushwork combines with the figure’s Pan-Indian iconography to produce a mythic composition of woman and nation, emblematic of a new idealism within Indian national discourse by the early 20th century.

Notes:

[1] Sister Nivedita, “Art Appreciations,” The Complete Works of Sister Nivedita, volume III (Calcutta: Ramakrishna Sarada Mission, Sister Nivedita Girls’ School, 1955), pp. 58–59.

[2] Tapati Guha-Thakurta, The Making of a New ‘Indian’ Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1992), p. 255.

[3] Sumathi Ramaswamy, The Goddess and the Nation: Mapping Mother India (Durham: Duke University, 2010), p. 15–16; Guha-Thakurta (1992), p. 259.

[4] Ramaswamy (2010), p. 15.

[5] Guha-Thakurta (1992), pp. 78–116; Iftikhar Dadi, Modernism and the Art of Muslim South Asia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2010), p. 48–60.

[6] Naela Aamir and Aqsa Malik, “From Divinity to Decoration: The Journey of Lotus Symbol in the Art of Subcontinent,” Pakistan Social Sciences Review, volume 1, number 2 (Dec 2017), p. 206.

[7] Diana L. Eck, Darśan: Seeing the Divine Image in India (New York: Columbia University, 1998), p. 28, 106.

[8] Guha-Thakurta (1992), p. 255.

Additional resources

Iftikhar Dadi, Modernism and the Art of Muslim South Asia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2010).

Diana L. Eck, Darśan: Seeing the Divine Image in India (New York: Columbia University, 1998).

Tapati Guha-Thakurta, The Making of a New ‘Indian’ Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1992).

Tapati Guha-Thakurta, Monuments, Objects, Histories (New York: Columbia University, 2004).

Monica Juneja and Sumathi Ramsawamy, editors, Motherland: Pushpamala N.’s Woman and Nation (New Delhi: Roli Books, 2022).

Sumathi Ramaswamy, The Goddess and the Nation: Mapping Mother India (Durham: Duke University, 2010).

Gayatri Sinha, “Cult of the Goddess: Gender and Nation: From Bharati to Bharat Mata,” Iconography Now: Rewriting Art History? (New Delhi: Sahmat, 2006), pp. 547–56.