Striding atop a mountain peak wearing a look of determination on his face, Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan shows a young Mao Zedong ready to weather any storm. In picturing a moment in Chinese Communist Party history, Liu Chunhua celebrated Chairman Mao (then in his seventies) and his longstanding commitment to Communist Party ideals. Painted in 1967 at the dawn of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, this work uses socialist realism to portray Chairman Mao as a revolutionary leader committed to championing the common people.

Socialist realism and Mao paintings

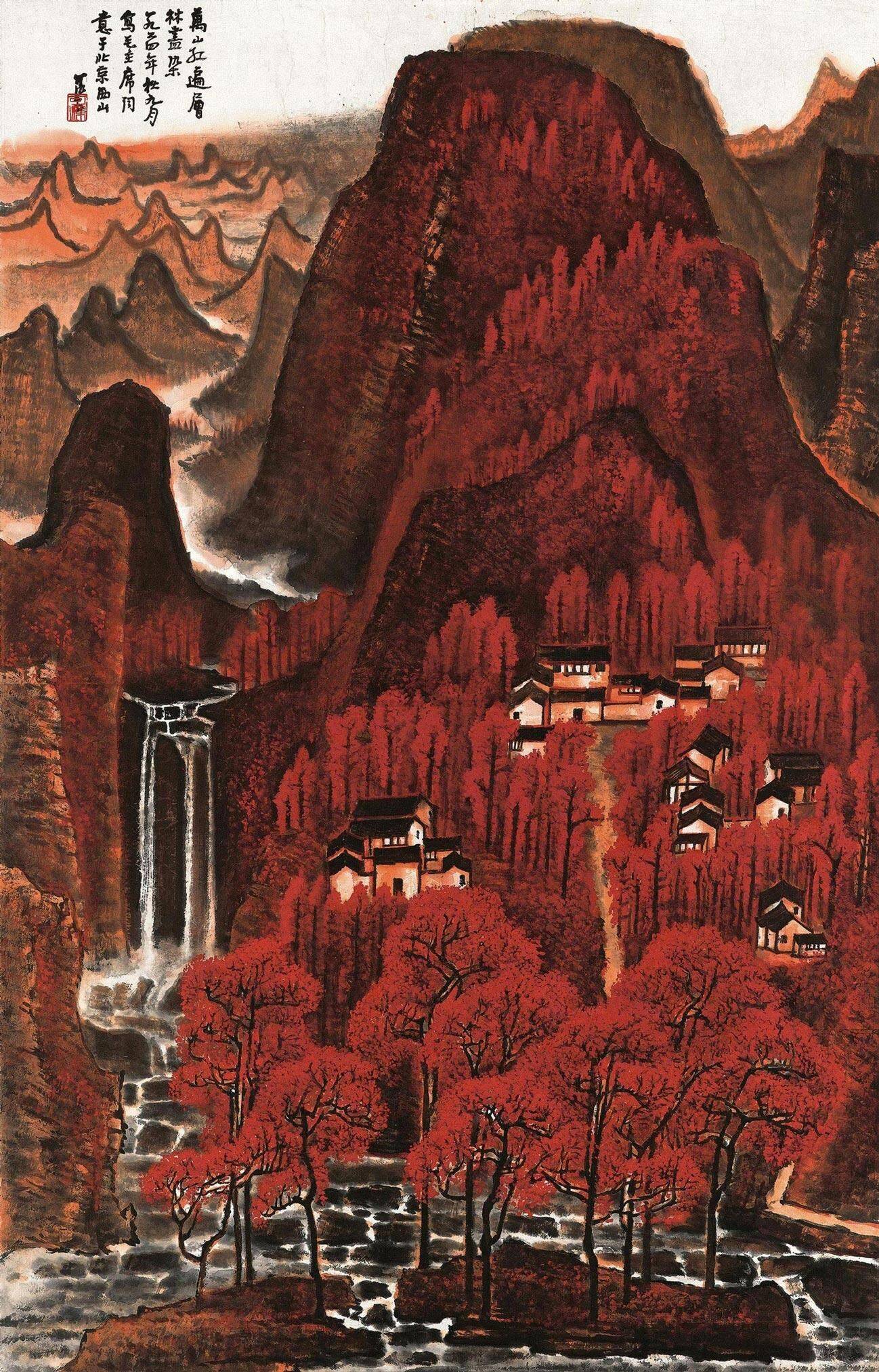

Li Keran, Ten Thousand Crimson Hills, 1964, hanging scroll, ink and color on paper (collection of the artist’s family, Beijing)

During the Cultural Revolution, artists focused on creating portraits of Mao, or “Mao paintings,” which represented Mao’s effort to regain his hold after bitter political struggles within the party. With the leadership of Mao’s last wife, Jiang Qing, the movement aimed to quell criticisms of Mao in drama, literature, and the visual arts. More broadly, it aimed to correct political fallout from the disasters of the 1950s, especially the widespread famine and deaths that resulted from the Great Leap Forward, and reinvigorate Communist ideology in general. In the years that followed, Mao would lead the country through a decade of violent class struggles aimed at purging traditional customs and capitalism from Chinese society.

In the early years of the Cultural Revolution, artists such as Liu Chunhua turned to a style known as socialist realism for creating portraits of Mao Zedong. Socialist realism was introduced to China in the 1950s in order to address the lives of the working class. Suitable for propaganda, socialist realism aimed for clear, intelligible subjects and emotionally moving themes. Subjects often included peasants, soldiers, and workers—all of whom represented the central concern of Mao Zedong and the Communist Party. Modeled after works in the Soviet Union, paintings in this style were rendered in oil on canvas. They notably departed from Chinese hanging scrolls in ink and paper, such as Li Keran’s Ten Thousand Crimson Hills, painted in 1964.

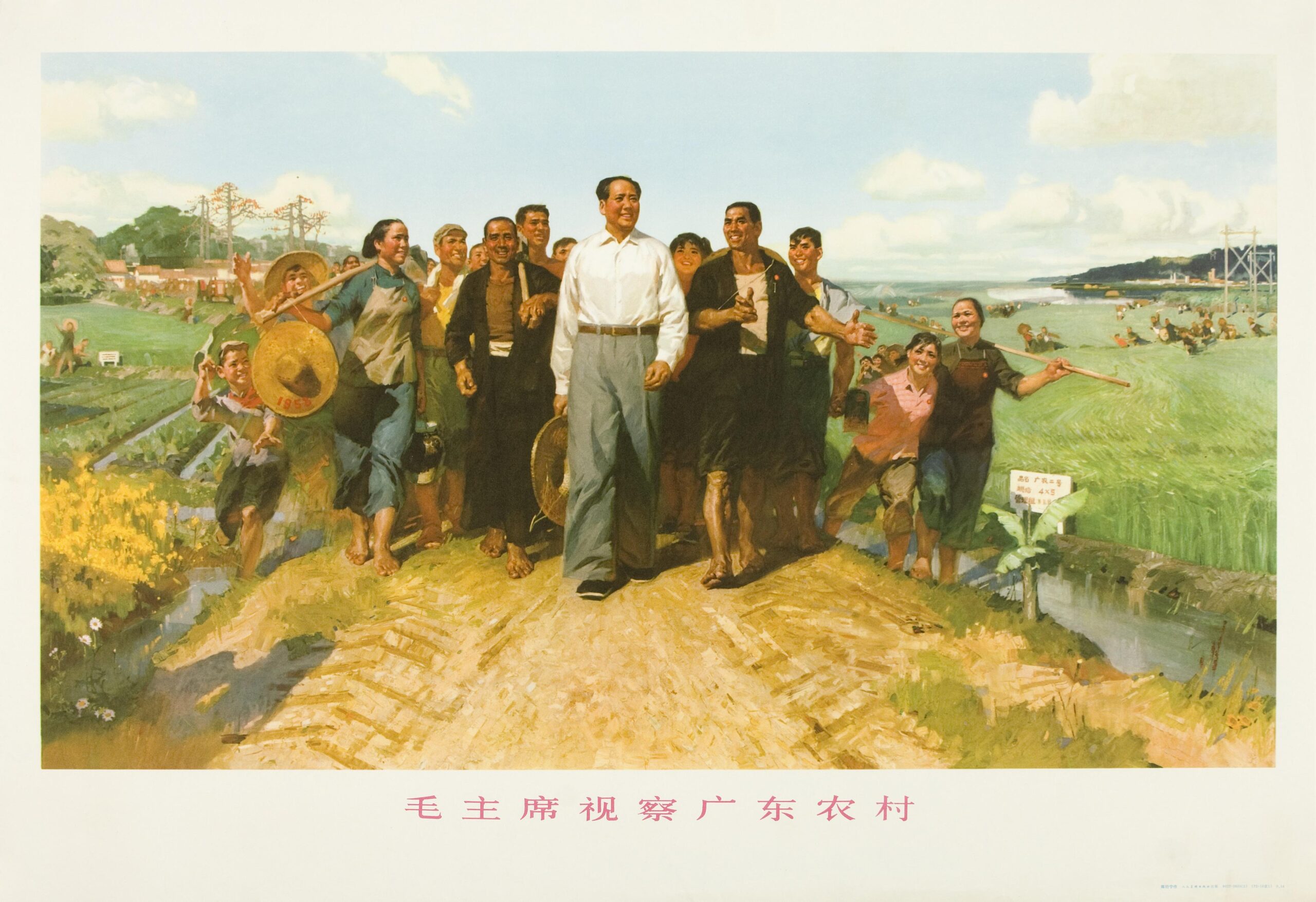

Standardized by the Central Propaganda Department, Mao paintings typically pictured the Chinese leader in an idealized fashion, as a luminous presence at the center of the composition. Unlike Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan, portraits usually depicted Mao among the people, such as strolling through lush fields alongside smiling peasants.

The Anyuan Miners’ Strike of 1922

Detail of Chairman Mao, Liu Chunhua, Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan, 1967, oil on canvas, 220 x 180 cm

Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan presents a critical moment in Chinese Communist Party history: Mao marching toward the coal mines of Anyuan, Jiangxi province in south-central China, where he was instrumental in organizing a nonviolent strike of thirteen thousand miners and railway workers. Occurring only a year after the founding of the Chinese Communist Party, the Anyuan Miners’ Strike of 1922 was a defining moment for the Chinese Communist Party because the miners represented the suffering of the masses at the heart of the revolutionary cause. Many of the miners enlisted as soldiers in the Red Army, intent on following the young Mao toward revolution.

Painting nearly half a century after the Anyuan Miners’ Strike, Liu Chunhua created Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan for a national exhibition. Liu Chunhua was a member of the Red Guard, or the group of radical youth whose mission was to attack the “four olds” (customs, habits, culture, and thinking). To create this painting, he studied old photographs of Mao and visited Anyuan to interview workers for visual veracity. Based on his findings, he rendered Mao wearing a traditional Chinese gown rather than Western attire, which is more commonly seen in portraits of Mao created during the Cultural Revolution. The cool color tonalities of Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan also differ from other Mao paintings, which tended toward warm tones with clear, blue skies, such as Chen Yanning’s Chairman Mao Inspects the Guangdong Countryside. Others often featured vibrant red accents—red being the color of revolution. Instead, Liu Chunhua opted for deep blue and purple hues to capture Mao’s determination as he marched to address the plight of those suffering.

From the painting by Chen Yanning, Chairman Mao Inspects the Guangdong Countryside, 1972, oil on canvas, 172 x 295 cm (Sigg Collection)

Detail of telephone pole and dam, Liu Chunhua, Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan, 1967, oil on canvas, 220 x 180 cm

In Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan, Liu Chunhua adapted Chinese landscape conventions to a new style and purpose—an evocative portrayal that suggested that Mao was capable of leading the country toward revolution. He pictured his subject emerging atop a mountain with clouds of mist below. In China, landscapes such as this often evoked immortal realms, or extraordinary sites invested with the misty vapors of the mountain. However, a telephone pole is discernible in the lower left corner of the composition, and water cascades from a dam in the right—hints of modernity within the ethereal landscape. With an umbrella tucked beneath one arm and the other hand clenched into a fist, and wearing windswept robes, Mao appears superhuman, yet also practical and charismatic.

As a prominent icon in the Cultural Revolution, Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan celebrated the grassroots nature of revolutionary history and cultivated devotion to Mao during a tumultuous time. As a brilliant example of Chinese Communist Party propaganda, it was reportedly reproduced over nine hundred million times, and distributed widely in print, sculpture, and other media.