A single dramatic overhead shot captures the artist covered in a viscous mud, clothed only in a pair of white boxers, on his side apparently struggling to free his left leg from the thickly piled muck atop which he lies. The mud forms irregular streaks and blobs atop a gravel surface. Shiraga Kazuo, Challenging Mud (Doro ni idomu), 1955 (2nd execution) © Shiraga Fujiko and Hisao and the former members of the Gutai Art Association

How might an artist react meaningfully in the aftermath of Japan’s defeat, and its near total destruction, at the close of the Second World War? Kazuo Shiraga’s 1955 performance work, Challenging Mud, proposed a rethinking of the boundaries and definitions of art making to clear a path forward.

The Gutai Art Exhibition

Shiraga performed his body/mud composition in the front courtyard of Tokyo’s Ohara Hall three times over the run of the first Gutai Art Exhibition. The photographs that survive record the different effects of each iteration of the performance. Each time Shiraga molded, smeared, and grappled with a different combination of cement, kabetsuchi, and aggregates such as sand and gravel. Somewhere between painting, sculpting, and wrestling, Kazuo’s radical actions defied categorical boundaries.

Two men appear in the frame, shot at a low angle. The artist is at the center of the shot in boxers only, his arms and legs subsumed in the thickly piled mud. The other is clothed, squatting at left, holding a film camera. Challenging Mud (Doro ni idomu), 1955, 1st Gutai Art Exhibition, Ohara Kaikan, Tokyo (Third Execution) © Shiraga Fujiko and Hisao and the former members of the Gutai Art Association

This emphasis on experimentation through the chance effects of action prefigured the proliferation of performance and intermedia practices that defined so much art in the 1960s and 70s, and has earned this work a place in art history. Mid-1950s Tokyo art-going audiences were accustomed to styles of painting promoted by the art academies, institutionalized artist associations, and art critics including surrealism, modernist abstraction, and proletarian arts, so they were unprepared for the genre-upending, aesthetic violence of Shiraga’s performance.

A pile of mud bearing an array of marks—indentations, cavities, and smears—sits at the center of a gravel field shot from a birds-eye view. A man, fully clothed in a casual suit, stands at left with hands behind him, head turned to directly face the camera following the convention of photographing painters next to their finished canvases. Shiraga Kazuo, Challenging Mud. (Doro ni idomu), 1955 (3rd execution). Postcard © Shiraga Fujiko and Hisao and the former members of the Gutai Art Association

Postwar democracy

Shock was likely the reaction Shiraga sought. Gutai leader Yoshihara Jirō demanded that members “create what has never been created before” as a rejection of Japanese conventions of social conformity that became linked, in the postwar period, to wartime nationalism. Much of the Gutai Art Association’s rhetoric followed the tendency in 1950s Japan to value American-style democracy and individualism as a response to the totalitarian aspects of wartime Japanese society, structures that had ended a mere ten years earlier.

Marxist-influenced political philosophers, argued that Japanese wartime fascism had been rooted in a lack of awareness of personal political power and social agency, a situation they described as insufficient to develop a sense of modern subjectivity. They argued that Japan had retained a feudalist outlook based in strict social hierarchies that allowed individuals to avoid personal responsibility by following those of a higher rank, including ultimately, the Japanese emperor.

Nine months after the performance, Shiraga illustrated a manifesto that defined what he termed creative individualism with a series of documentary photographs from his second and third performances. The text insisted on the need to nurture self-expression to create a foundation of “psychic individualism” (a recognition of individual autonomy) to guard against totalitarianism and cultural restrictions. Shiraga pushed back against the desire to create great works of “social significance or commercial value,” arguing that a focus on spirit and personal expression will create works that connect to others and accrue cultural value. [1]

left: incendiary bombs are dropped from U.S. B-29s, Kobe, Japan, June 4, 1945 (photo: U.S. Army); right: Osaka, Japan, 1945 leveled by fire-bomb attacks by U.S. B-29s (photo: U.S. Army, Library of Congress)

For the Gutai artists, the value of democracy lay both in its privileging of individualism over conformity and its upending of social hierarchies. Near the end of WWII, Allied forces led by American B-29s, firebombed many of Japan’s major urban centers including Osaka and Kobe, cities close to Ashiya City where the Gutai artists were based. After WWII, reconstruction was slow and was primarily carried out with inexpensive and readily available materials such as kabetsuchi, which was widely used for residential reconstruction in the decades following the war. Shiraga’s unstudied abstract mark-making that used kabetsuchi positioned Challenging Mud as a work of art that anyone could potentially recreate. In this way, Shiraga’s work was a direct attack on what the Gutai artists perceived as the elitist politics of the institutional art world centered in Tokyo (where Challenging Mud was staged).

A challenge to painting

The ambitions of Challenging Mud were not simply political. Shiraga’s work was part of a broader redefinition of art by the Gutai artists. Gutai artists used the term “e” (picture in Japanese), to describe their work, in contrast with the term “kaiga,” commonly used to refer to paintings in a fine art context after Meiji period reforms modernized Japan’s art world using a European model. “Kaiga” 絵画, written with Japanese characters that reference a flat image and a wall-hung, stretched canvas format.

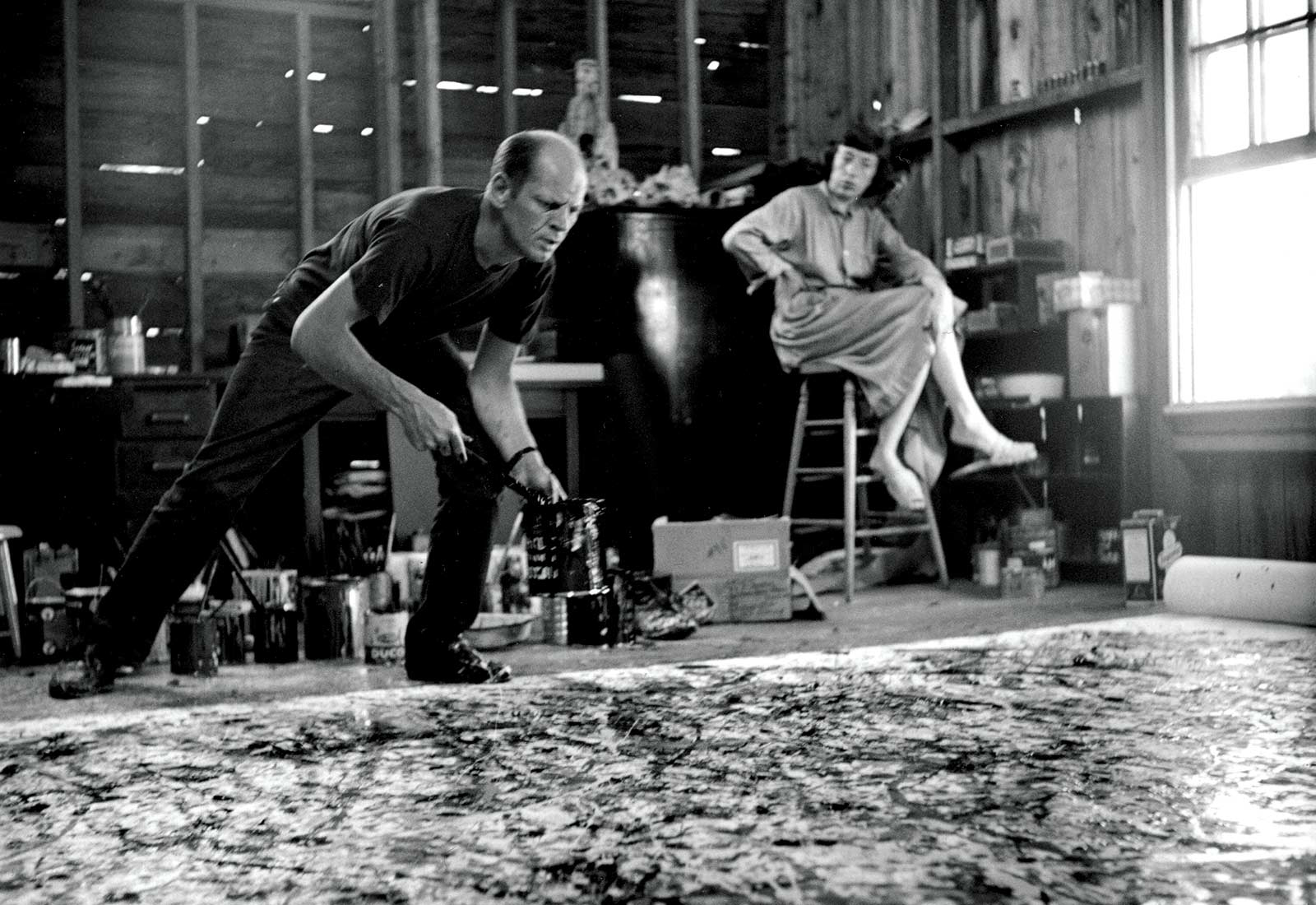

Hans Namuth, Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner, 1950, gelatin silver print, 28 x 27.3 cm © Hans Namuth Estate, Center for Creative Photography

In abandoning that term for “e” 絵, which simply refers to picture-making, Gutai artists questioned the basic formats and boundaries of modern painting. Gutai artists’ approach drew inspiration from mass-media photographs of Jackson Pollock painting not on an easel but on canvas spread across the floor. But while Pollock’s work ultimately resulted in wall-hung paintings, Gutai artists often moved beyond the canvas entirely. Through media including performance, installation, and electrical technology, they pursued a more expansive vision of artistic creation that embraced participation, amateurism, and everyday creativity by looking to, for example, the spontaneity of children’s art as an ideal. Nevertheless, the photographic documentation of Challenging Mud retains some relationship to painting. Specifically, Shiraga had a nameplate placed next to one iteration of the mud pile and had himself photographed standing next to this completed composition, a parallel with exhibition practices, but one that critiques conventions of painting.

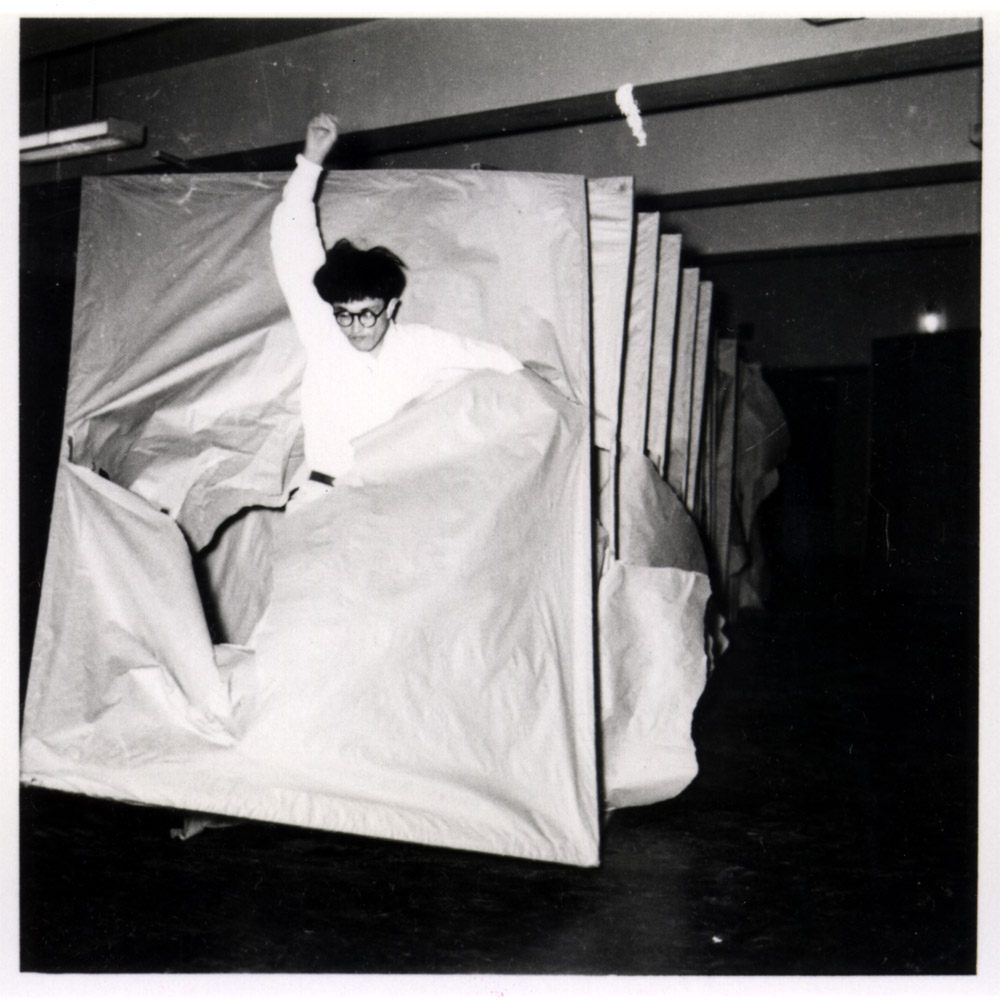

Murakami Saburō, Passing Through, 1956, Performance view: 2nd Gutai Art Exhibition, Ohara Kaikan, Tokyo, 1956 © Makiko Murakami and the former members of the Gutai Art Association

Violence and masculinity

Art historian Namiko Kunimoto has argued that violence was a recurring theme in Shiraga’s overall artistic practice. In the 1950s, Pollock was understood by some critics to represent the “end of painting,” and an impasse to future creative expression. The Gutai artists responded with destructive acts—the throwing of glass bottles filled with paint and ripping through paper stretched across wooden frames.

Fujita Tsuguharu, Honorable Death on Attu Island (Attsutō Gyokusai), 1943, oil on canvas, 76 x 102 inches (The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo)

Acts of violence within the context of art making could also serve as a means for artists in the postwar period to reject state-sponsored wartime propagandistic painting. For example, in the infamous wartime painting by Fujita Tsuguharu, Honorable Death on Attu Island (Attsutō Gyokusai), a violent mass of writhing soldiers form a muddy pile of monotone bodies, forgoing individuality in support of national spirit—an ethos often understood in the West through the kamikaze pilot who sacrifices his life to maintain the honor of family and country. By contrast, Shiraga struggled alone with the mud to reveal both its material character and his own individual spirit through a process of spontaneous, physical mark-making. In this way, Shiraga presented the violence in his art as a means of shifting the destructive energy of the war to a creative process that he used to strengthen his individuality.

However, throughout Shiraga’s practice, violence is also marked as specifically masculine through references in his titles and materials to East Asian male archetypes including the classical warrior, the eccentric monk, and even the boar hunter. Challenging Mud, likewise, seems to gesture toward the soldier in the trenches; note for example Shiraga’s cropped GI-style haircut and, of course, the mud. Yet simultaneously, the work’s aesthetic—a one-on-one match between the artist and a circle of mud (with the artist clad in white shorts reminiscent of a white fundoshi) presented at the exhibition’s opening—evoked the image of a sumo match or the doronko matsuri, both ritual events featuring masculine figures associated with the inauguration of yearly cycles. To a certain degree, Shiraga presents himself as masculine hero echoing the American Abstract Expressionist model of the artist as a heroic individualist expressing his spirit through gesture. However, through violent performance and the abandonment of paint and canvas, Shiraga pushed this model in a distinct direction informed by the context of postwar Japan.

Happenings and media events

In some ways early Gutai works were ahead of their time. They used novel settings—parks, theaters, rooftops—and innovative formats—performance, installations, events—to maximize the accessibility and impact of their works. These novel approaches drew the attention of the press, and, in a strategy replicated several times, Shiraga’s Challenging Mud was specifically staged for a Mainichi newsreel. Photographs were also circulated through the Gutai journal, with several issues ending up in the United States. This led American performance art pioneer Allan Kaprow to include images of Challenging Mud in his seminal compendium of 1960s experimental works Assemblages, Environments and Happenings (1966), alongside art stars Jackson Pollock, Robert Rauschenberg, and Claes Oldenburg. Placed amongst other messy, deskilled, immersive, and event-based works, Challenging Mud’s performative ephemerality was only captured by the documentary camera and circulated through reproductive media networks. In such a context, Challenging Mud’s emphasis on materiality and its challenge to painting fades in favor of the camera frame. This prefigures the engagement with media in 1960s art movements including happenings and performance art—temporary events captured through photography—as well as land art—filmed and photographed in order to bring physically distant installations to the attention of urban art audiences. Ultimately, it is Challenging Mud’s complex web of references, at the intersection of the post-WWII Japanese art world and the international art scene, that continues to draw audiences to its photographic remnants.