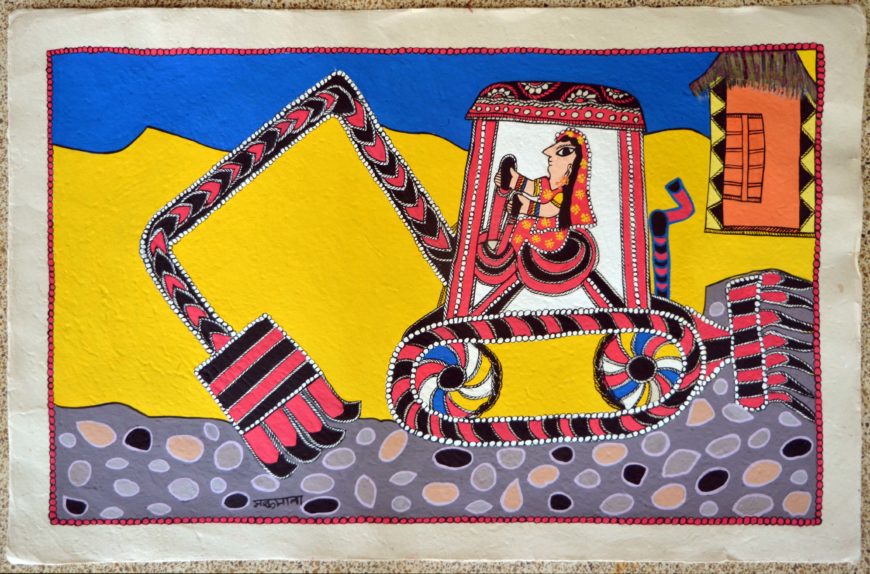

In her “Woman with a Backhoe”, Madhumala shows a woman preparing to pave one of Janakpur’s new wide roads, 2019, acrylic on handmade lokta (daphne) paper, 30” x 20” (JWDC; photo: Claire Burkert)

The long arm of a magenta and black backhoe claws at the surface of a rocky road, while the female operator of the enormous machine manipulates it with confidence and ease. The composition’s brightly-colored background and the intricate patterns are typical of painting amongst the Maithil communities in India and Nepal. While the artist of this composition, Madhumala Mandal, first learned to paint on the mud walls of her home, she is part of a generation of Maithil artists to convert their mural painting traditions to paper. Madhumala’s choice to include a strong female figure operating heavy equipment—rather than more traditional subjects like Hindu gods and goddesses—illustrates the diverse ways that Maithil painters are using imagery from their own lives and sharing their personal perspectives in their artwork.

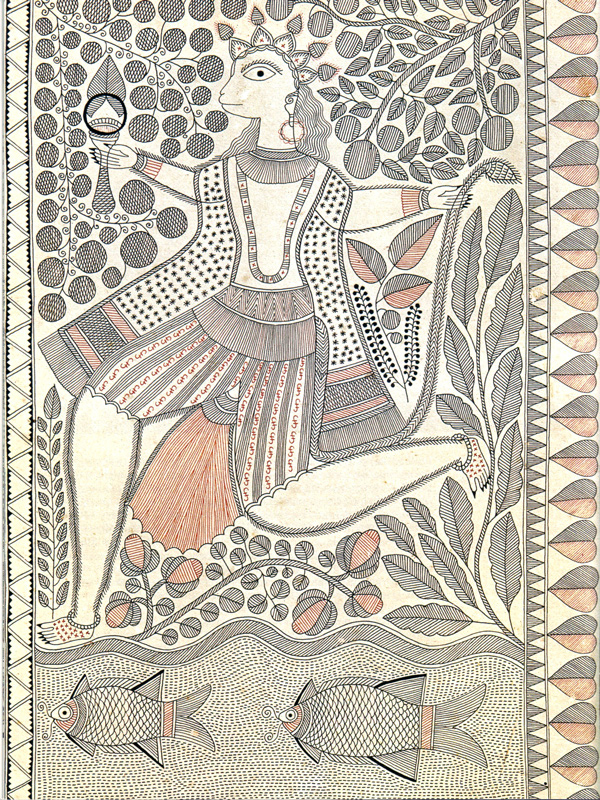

Unknown artist (Madhubani district, Mithila, Bihar, India), the Hindu god Krisnha playing his flute while standing on the back of a multi-headed serpent (perhaps the demon Kaliya), mid-20th century, ink and color on paper, 27.9 x 44.1 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art)

Where is Mithila and who are the Maithil people?

Map of India with the Mithila region indicated (underlying map © Google)–will be making adjustments once hear from authors

The historical kingdom of Mithila once covered an area that stretched from what is today northern Bihar and Jharkhand states in India and the eastern plains of Nepal. The people who live in this region refer to themselves as the Maithil people and they speak a language known as Maithili. The majority of today’s Maithil population are Hindus who maintain a rigid caste hierarchy and a system of patriarchy that often requires women to keep purdah (literally “curtain”).

Across all castes most families continue the practice of dowry and girls have only recently begun to receive access to formal education. In this social context, Madhumala’s female bulldozer operator is that much more radical: she is a woman doing work more typically assigned to men, in a society that traditionally limited the movement and activities of women.

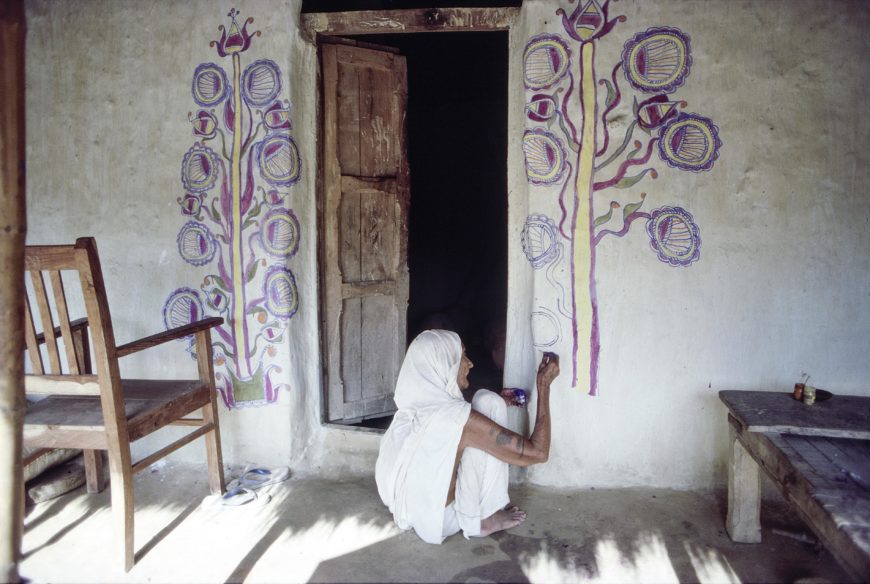

An upper-caste widow in Jitwarpur, India, painting lotus leaves at the entry of her home, 1988 (photo: Claire Burkert)

What is Mithila painting?

One arena in which women historically had agency was in the practice of painting. For generations, Maithil women from all castes painted auspicious (favorable) symbols onto the mud walls of their homes, a tradition that was passed through generations, from mother to daughter. The women made ritual paintings that invited the gods to bless an occasion such as marriage, with the auspicious symbols ensuring well-being, fertility and love.

Upper caste Maithil women painted images of deities, while women of both upper and lower castes depicted auspicious animals such as peacocks, elephants, tigers, birds and fish as well as bold geometric and floral patterns to border the windows and doorways of their homes. Women used materials from their daily lives to create these paintings: a stick wrapped with a piece of cloth for a brush and paints made from turmeric, milk, vegetables, earth, and soot. Gradually natural materials were replaced by synthetic pigments purchased in the market. In its traditional form, Mithila painting was an ephemeral art: women created devotional images on the exterior walls of their homes knowing full well that these paintings would be erased each year by monsoon rains or smoothed over with a fresh coat of mud (the first step in preparing walls for new decoration). Mud was often smoothed over the walls on the occasion of the new year—Jur Sital—creating a fresh palette.

Traditionally painted on the wall of a marriage chamber, the kohbar painting holds powerful spiritual significance for the young couple and their families. Sita Devi, Kohbar painting (detail) on paper, Bihar India (photo: Sumanjha1991, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Images of marriage and devotion

Weddings were important social events to honor with new murals. Upper caste women would paint a mandala (sacred geometric pattern) of lotus leaves on the walls of the kohbar ghar, the room of the bride’s house where a marriage would be consummated. [1] These paintings were made foremost for an audience of the gods, beckoning them to bless a marriage ceremony. A painting by artist Sita Devi illustrates the powerful symbolism of kohbar images. At the center of the composition is a stylized lotus flower with a phallic-like stem (a symbol of procreation and fecundity), radiating with six female faces. A kalasha or pot containing holy water appears next to the base of the lotus and represents domestic happiness. The sun god (Surya) and the moon (Chandra) appear at the top corners of the painting while the ideal, divine couple, Lord Shiva and his goddess consort Parvarti, stand in the lower left corner. Directly opposite the divine couple, in the lower right corner, are the newlyweds, with the groom wearing an elaborate wedding hat. Sita Devi includes depictions of parrots (representing love) as well as fish and turtles (auspicious, life-filled symbols)–all familiar fauna of Mithila. Two mythological birds, with their beaks touching, guide the destiny of the bride and groom.

Sita Devi, Monuments in Washington, DC, 1977, ink and colors on paper, Jitwarpur, Mithila, Bihar, India, 76.20 cm x 57.15 cm (Asian Art Museum, San Francisco)

Bharni and Kachni styles

Sita Devi’s technique of making outlines and filling the forms with bold color is known as the bharni style and is typical amongst artists in her Brahmin caste. When Sita Devi traveled to the United States in 1976, she used this bharni style to create paintings of the sites she visited, including the National Mall in Washington, D.C. In one painting, she depicts the Capitol Building–looking like a Hindu temple—surrounded by flowers. A thick purple band, representing the Lincoln Memorial reflecting pool, runs down the center of the composition, flanked on either side by trees and graves from the Arlington National Cemetery. Her strategy of representing three-dimensional forms (like architecture) as flat geometric shapes is typical of Mithila painting, as is the way she divides the composition into different scenes or geographical areas separated by borders.

Different from the bright palette of the bharni style used by Sita Devi, is an intricate linear style known as kachni that was traditionally the purview of Kayastha women (a caste of scribes and accountants). The kachni style was made popular by the artist Ganga Devi, who in addition to traditional kohbar images and scenes from the Hindu epic story The Ramayana, created paintings that reflected her personal lived experiences.

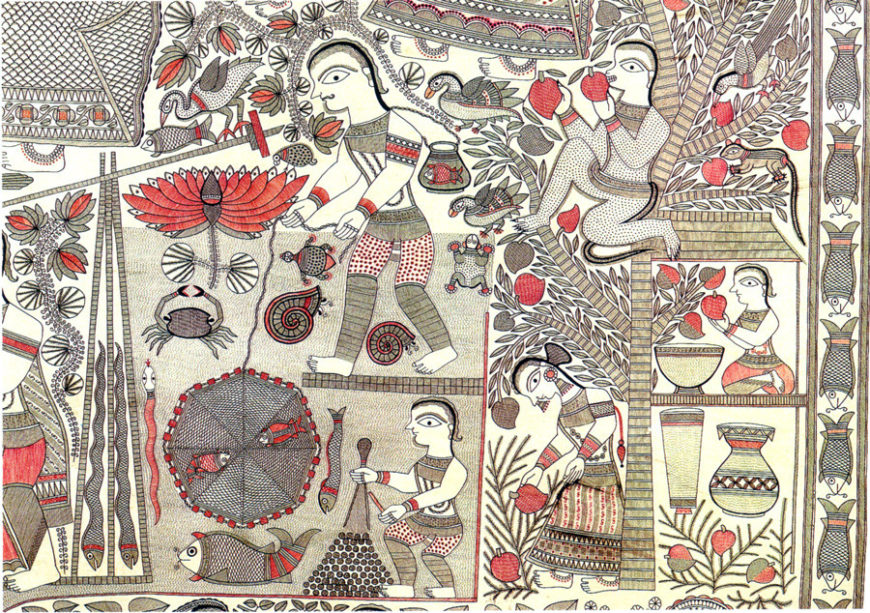

Ganga Devi, A Scene from Rural Mithila: Circle of Life (detail); inks on paper, 152 x 328 cm (full painting), 1983–85 (Crafts Museum, New Delhi, India)

A detail from Ganga Devi’s Cycle of Life series blends auspicious imagery (like fish, turtles, and lotus leaves) with scenes from daily life in Mithila such as fishing and picking mangoes. The Hindu god Hanuman, one of the heroes of The Ramayana, appears in Ganga Devi’s composition frolicking amongst the trees and eating ripe fruit, a sign that the god remains present in all activities.

From domestic wall paintings to the global art market

While there are now a great many artists who create paintings in the Mithila style, it was only in the second half of the 20th century that this long-standing painting tradition moved to paper and into the global art market. The art form was first documented by William Archer, a British colonial officer who encountered the paintings while doing reconnaissance in the Madhubani district of Mithila in the state of Bihar, India after a huge earthquake affected the region in 1934. [2] Three decades later, in the wake of economic devastation following a severe drought, Pupul Jayakar, the chairperson of the All-India Handicrafts Board, initiated a project in which Maithil women could earn much-needed income by converting their images into paintings on paper to sell in the market. Brahmin and Kayastha families in the village of Jitwarpur were particularly receptive to this new project, and created paintings on paper that were sold in New Delhi. In the 1970s, the German anthropologist Erika Moser challenged the notion that Mithila art was solely the domain of high caste Brahmins and Kayasthas when she encouraged Dalit (“untouchable”) women to create paintings on paper inspired by their tattoos (godana) and the designs on their houses. [3]

Rebati Mandal, At Work in the Brick Factory, acrylic on handmade (lokta, or daphne paper) 30” x 20” (collection of Susie Vickery; photo: Claire Burkert)

In Nepal, the move to convert murals to paper occurred later, in 1989, amongst a group of women in the city of Janakpur. They initially began by depicting traditional themes, however more recently they have created images that address aspects of their lives and the changing urban landscape around them–much like Madhumala’s backhoe and confident female operator. [4] A painting by Rebati Mandal, another Janakpur-based artist, illustrates these dynamic new subjects of Mithila painting in Nepal. Rebati depicts several male and female figures engaged in making bricks—the building blocks that literally construct the growing urban environment of Janakpur. In this composition, the artist shows us several perspectives at once: we see a birds-eye view of figures seated on a bright turquoise ground pressing clay into brick molds and feeding logs into the fiery pits of a kiln, while at the same time other figures, encountered at ground level, collect paychecks from a mustachioed foreman who sits in the corner. The shifting perspectives and vibrant palette convey a sense of movement and bustling activity that is reinforced by the laboring bodies in the painting. References to family life outside the brick factory–in the figure of the child who plays nearby and the baby held by a woman in an adjacent space–show the viewer another side of Mithila and the different roles that women play in the community.

While some scholars bemoan the loss of Mithila painting’s original purpose–to create auspicious kohbar images and Hindu iconography that speaks directly to the gods–and criticize the commodification of the art form on paper, many artists celebrate these new iterations of their painting practice. In fact, younger Maithil artists are of a generation who never learned wall painting and instead are starting fresh with the artform on paper and other surfaces. The vibrant tradition of Mithila painting, in both India and Nepal, has allowed women to not only earn income for their art but also to engage with the wider world.