Mahmoud Hammad, Arabic Writing no. 11, 1965, oil on canvas, 130 x 100 cm (Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut). Courtesy of the Family Estate of Mahmoud Hammad / Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation

The 1965 painting Arabic Writing no. 11, by Syrian artist Mahmoud Hammad, is composed of bright, interlocking shapes of textured pigment on a flat blue surface. Primary fields of color are arranged following a pictorial logic of cutout shapes rather than layers. The artist maintains distinct edges between the complementary color combinations: yellow-gold on red, red on navy, green against orange, and so on. The result is a consciously controlled abstraction. As if to exaggerate the constructed quality of the painting, Hammad adds one cartouche of loosely inscribed writing in the lower right—a nod to the expressive and mystical types of abstraction popular elsewhere.

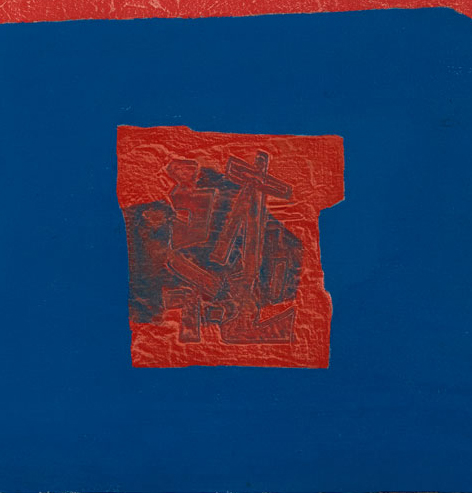

Cartouche (detail), Mahmoud Hammad, Arabic Writing no. 11, 1965, oil on canvas, 130 x 100 cm (Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut). Courtesy of the Family Estate of Mahmoud Hammad / Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation

One of five canvases Hammad exhibited at the 8th São Paulo Biennial in Brazil, Arabic Writing no. 11 represents a particular approach to abstract painting practiced by artists in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia. Hammad uses letter forms from the Arabic alphabet as the central elements of his compositions. As suggested by the titles of the other paintings he sent to Brazil, which include Arabic Writing nos. 8, 12, 13, and 14 in addition to no. 11, he based each composition on a text—phrases selected from Arabic literature, folk culture, or the Qur’an. In the case of Arabic Writing no. 11, its originating text is verse 36:58 from the Qur’an, “Peace, a word from the blessed Lord.”

Hammad is credited with establishing calligraphy as a pathway for generating abstract art in Syria. [1] However, it is a curious feature of Hammad’s work in the 1960s that he manipulated the texture, color, and spatial ratios of words to the point of illegibility. Even though the ligatures and dots among the painted shapes of Arabic Writing no. 11 make visual reference to Arabic orthography, neither native speakers nor foreign observers could decipher the words without assistance from the artist. Hammad in fact took steps to cloak linguistic meaning. Although he kept detailed studio logs that list the originating phrases of the paintings, he tended to exhibit them under generic series titles such as “writing” or “composition.”

The decisions behind an abstract painting such as Arabic Writing no. 11 raise important questions about art in the 1960s, a decade of independence movements and liberation struggles. What meanings can abstract art hold for an artist working in a formerly colonized country? In the context of an ex-colonial nation-states such as Syria, which claimed its independence from France in 1946, many activists looked to art and culture to help provide roadmaps to nation-building and modernization, often in the guise of figurative arts that documented traditions past and future. Hammad did not pursue this route in Arabic Writing no. 11. What meanings, then, did he expect the forms of his work—which are based on text but cannot be read—to convey to audiences?

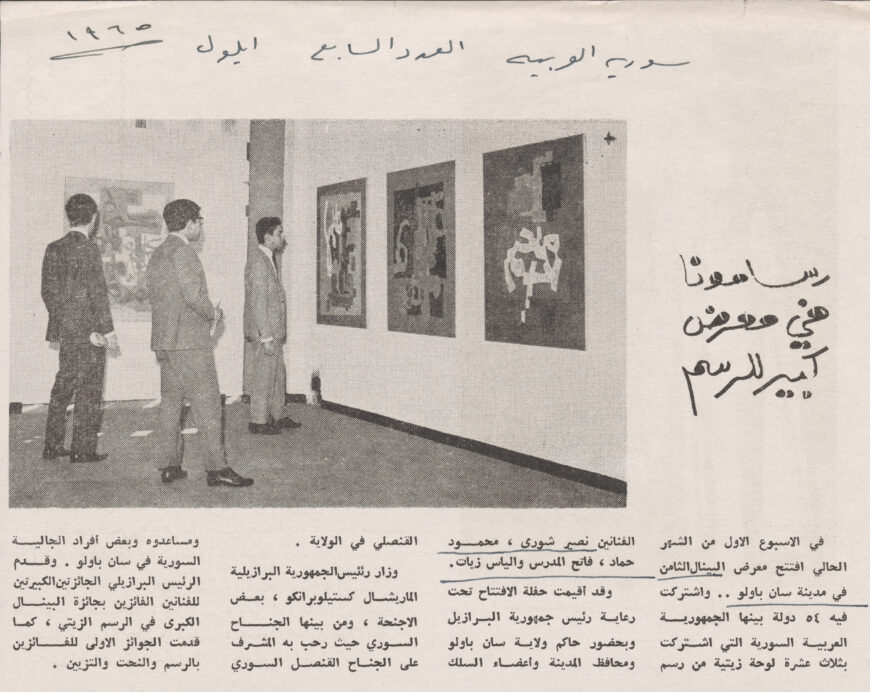

“Painters in a Big Painting Exhibition,” clipping with installation photograph showing Hammad’s paintings, in Suriya al-Arabiyya (September 1965). Courtesy of the Family Estate of Mahmoud Hammad / the Arab Artist Archive, al Mawrid Arab Center for the Study of Art at New York University Abu Dhabi

International display

Biennial art exhibitions—that is, large-scale international events recurring on a biannual schedule—offered ex-colonial nations opportunities to highlight the achievements of their artists. The first such event, the Venice Biennale, emerged from a mercantile context of industrial and imperial fairs. But, following the Second World War, a period of Cold War-era jockeying for cultural prestige produced a wave of new biennials and triennials in cities such as São Paulo, Alexandria, New Delhi, Paris, Tokyo, and elsewhere.

The four Syrian artists who participated in the 1965 Biennial all exhibited versions of abstract painting. The selections, which were overseen by Syria’s ambassador in Brazil in collaboration with the Syrian Ministry of Culture, reflect an understanding of the exhibition as a site of ideological contestation where the style of a country’s art might be scrutinized as evidence of political commitment. Within Syria itself, varieties of realist and national art were favored due to their perceived value for educating the populace about shared aspirations. Following a March 1963 military coup that brought a populist Arabist political party to power, cultural politics in Syria had roughly aligned with the Socialist bloc. Many leading intellectuals, informed by varieties of Marxist art criticism, harbored antipathy toward what they considered decadent abstract arts based upon bourgeois individualism and expressive pleasure. Nevertheless, as the new Syrian government perceived a need to shore up its legitimacy abroad, it selected abstract art as a primary form of representation. The fact that Brazil had recently suffered a coup of its own, which pushed the country into alignment with the United States, likely served as another indication of jury preferences for abstract work. [2]

Language games

Many of Hammad’s contemporaries mounted justifications for abstract art based upon the historical precedents found in Arab-Islamic art, including highly innovative geometric surface designs in architecture and illuminated books, which provided a basis for characterizing abstraction as a local practice rather than foreign imposition. But Hammad professed relatively little interest in reviving motifs from the past. As he explained in a 1965 essay, he considered abstraction to be a shared language of contemporary life; processes of industrialization had subjected all areas of developed society to abstraction. [3]

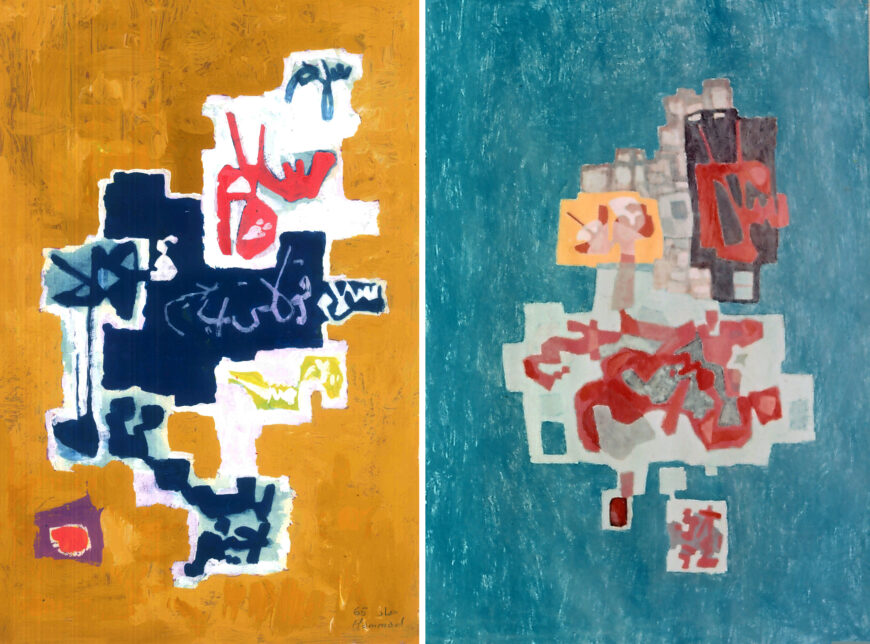

Sketches based upon the same phrase as Arabic Writing no. 11, 1965. Left: acrylic on paper, 30 x 20 cm; right: watercolor on paper, 45 x 30 cm. Courtesy of the Family Estate of Mahmoud Hammad

For Hammad, the already abstract status of Arabic characters made them ideal vehicles for responding to contemporary conditions. To create Arabic Writing no. 11, Hammad made numerous studies of ways to transform the handwritten outlines of “Peace, a word from the blessed Lord” in Arabic into experimental forms. He duplicated and mirrored words, moved and stacked elements, adjusted color combinations, and filled in negative spaces and gaps. Planes of contrast color sometimes appear as framing devices, other times as lines of segmentation. Once Hammad transferred his preferred arrangement to canvas, he began to build up shallow impasto volumes. This further transformed the physical presence of his different shapes.

Animation showing the transformation of the Arabic words of the verse “Peace, a word from the blessed Lord” into an artistic composition, Mahmoud Hammad, Arabic Writing no. 11, 1965 (animation created by Anneka Lenssen)

Even though Arabic Writing no. 11 stems from a Qur’anic passage, the final painting relinquishes its visual connections to divine speech. In place of identifiable textual referents, the impasto forms of meticulous brushwork seem to speak of human agency. They are records of how Hammad decided to place certain colors and volumes into certain places on the surface of his painting.

In other paintings, Hammad selected texts that further emphasize the arbitrary nature of language conventions. Several of his early abstract paintings use the phrase abjad hawaz, which are pseudowords made from the first seven letters of the Arabic alphabet as a basis for recollecting their sequential order. Even when Hammad kept the letters of abjad hawaz in discernable forms, the words themselves hold no lexical meaning.

Abstraction as educational practice

Hammad’s view of abstract art was greatly informed by his work as an educator. From 1962 until his death in 1988, the artist taught at the Faculty of Arts at the University of Damascus, first as the head of the painting department and later as the Dean. Charged with designing a curriculum to cultivate new Syrian artists oriented to Socialist futures, Hammad held the view that comprehensive training should engage all trends and approaches. He took the lead in recruiting colleagues from France, Italy, Poland, and Bulgaria to teach at the school. The faculty rejected rote training in naturalistic depiction and put emphasis on materials and process, designing Bauhaus-inspired exercises meant to produce immersive knowledge of qualities such as texture. These exercises produced abstract results in the short-term, but were thought to prepare students to go on to incorporate their insights into any style in the future.

Whenever Hammad defended his embrace of abstract painting to the Syrian press, he emphasized the value of experimentation and self-discovery. Mobilizing a Socialist vocabulary of struggle and heroism, he likened the experimental capacity of the artist to that of a revolutionary. To bring about change, he argued, it was insufficient to depict scenes of inverted power, such as “the victory of Arab armies over the French,” or the “rebellion of the Black people over their white tormenters.” [4] Rather, a truly restorative and humanist art entailed manipulation of aesthetic form at a deep level, such as the level of mind-body connections. Echoing revolutionary discourses in Algeria, Cuba, and elsewhere, he and his colleagues spoke about using art to produce “new men” and new societies.

Abstracted words (detail), Mahmoud Hammad, Arabic Writing no. 11, 1965, oil on canvas, 130 x 100 cm (Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut). Courtesy of the Family Estate of Mahmoud Hammad / Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation

Huroufiyah

Hammad’s 1965 painting, Arabic Writing no. 11, expands how we understand artistic uses of Arabic letters as a historical phenomenon. Scholars have come to recognize the incorporation of Arabic calligraphy into modern painting as the major development of the SWANA region in the 20th century. Although different names for the trend have been proposed, a 1990 study by critic Charbel Dagher popularized the umbrella term “Huroufiyah,” based on the Arabic word for “letters.” [5] Recent scholarly commentaries have focused on the problem of tradition as a resource for modern artists. Iftikhar Dadi demonstrated how artists working in postcolonial South Asia used Arabic texts to offer commentary on membership in the transnational community of Muslim believers. [6] Nada Shabout has highlighted how artists in Arab nation-states practiced Huroufiyah in response to a national identity crisis by connecting with the past yet still allowing for invention. [7]

In the case of Hammad, the artist largely avoided a dynamic of revivalism by separating his painting from calligraphy as a traditional art. In this, he had company from among other Arab and Muslim artists. In January of 1965, the arts writer Ghazi al-Khaldi assessed the trend of using alphabetic characters in plastic arts, situating Syrian artists among a wide cohort of painters using calligraphy to escape from representational art. [8] Al-Khaldi cited European artists such as Paul Klee, and introduces contemporary Arab practitioners such as Saad Kamel, from Egypt, and Ahmed Mohamed Shibrain from Sudan. What the artists have in common, al-Khaldi reports, is that the letter allowed for total freedom in creation. Hammad pushed his shapes much further in this direction than many other Huroufiyah artists. His boldest work with Arabic letters made illegibility into an artistic virtue. Beginning from the already abstract forms of written language, Hammad went on to deconstruct and reconstruct the shapes to arrive at other possible forms of painting. This multiplied the available avenues for producing abstract art.