Bharat Mata or “Mother India” is a powerful political symbol in South Asia, which over time has come to embody the idea of the Indian nation and its territory. Typically shown in the guise of a Hindu mother goddess, Bharat Mata first emerged as an idea and visual form in the late 19th century, when anti-colonial sentiments across the Indian subcontinent grew to new heights. In the 20th century, the symbol proved a crucial mobilizing force for the Indian national movement and was used to unify a vast and diverse population in the fight for independence from British colonial rule. Following the partition of 1947, when India and Pakistan first gained independence and statehood, Bharat Mata and her iconography have persisted as important sites of artistic and political contestation. Contemporary artists continue to look to Bharat Mata as a way to interrogate the difficult relationship of nation, gender, religion, and citizenship in South Asia.

Mother India in politics

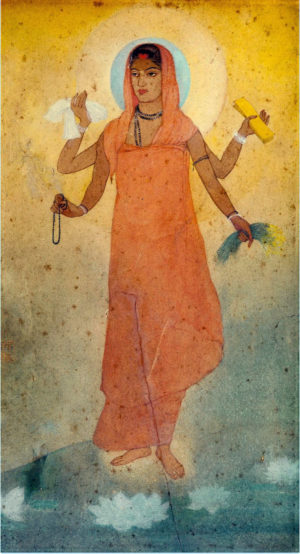

Abanindranath Tagore’s iconic 1905 painting of Bharat Mata announced the arrival of Mother India as a political icon in South Asia. But the painting was only one manifestation of a much wider practice of picturing the territorial idea of India in the 20th century, as the symbolic personification gained greater visibility and political traction. The concept of Bharat Mata acquired powerful political valence during the Indian national movement as a sign of political liberation, self-sufficiency, and hope. An important rallying cry by the 1930s, Bharat Mata provided tangibility and tactility to a shifting national imagination and a way to unify a disjointed body politic divided by caste, class, ethnic, linguistic, regional, and religious differences. [1]

Bharat Mata’s popularity was reinforced by political leaders of the time. Jawaharlal Nehru, a prominent advocate for Indian independence who would become India’s first Prime Minister in 1947, devoted several pages to Bharat Mata in his famed political memoir, The Discovery of India (1946). For Nehru, Bharat Mata was not just an “anthropomorphic entity” for the country, nor a reference to India’s “good earth.” [2] Bharat Mata stood more simply for “the people of India” and the political potential in their variety and collectivity. [3]

Bharat Mata sculpture, Yanam, India (photo: Dvssrinivas, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Amid this increase in Bharat Mata’s visibility and popularity as a sign of the nation came important shifts in her iconography, which would see the figure, especially in print and political paraphernalia, shed the fragile idealism of Tagore’s early painting. In these later images, Bharat Mata embraces her role of goddess of the nation with greater confidence, a transformation enabled by a deepening identification of Bharat Mata as a Hindu deity.

Bharat Mata, in this sense, is often clad in a form-fitting sari, bedecked in a crown and heavy jewels, which overwhelm her wrists, neck, and waist, foregrounding her femininity, fertility, and divinity. Bharat Mata, in these images, often holds a spear or the Indian tri-color flag in her hand, and she is sometimes accompanied by a lion, recalling the ferocity of Durga and her mount. She is often depicted as a well-armed figure riding a lion or tiger. The lion has a long association with religion and political power in South Asia beyond Hinduism. It is an important sign of royalty and power in Buddhist doctrine. It was also famously used as a royal emblem by the Mauryan kings, an early Indian empire that unified large swathes of the Indian subcontinent between 322–184 B.C.E.

Mother India in maps

Bharat Mata’s form also becomes linked to the territorial map of India and is sometimes shown hovering above, merging with, or sitting near the Indian subcontinent. In some cases, Bharat Mata’s iconography becomes interchangeable with the map of the Indian subcontinent. A notable example of this is the Bharat Mata Mandir in Varanasi, inaugurated by Mahatma Gandhi in 1936. Dedicated to Mother India, the temple houses an elaborate marble map of the Indian subcontinent which is worshipped in place of an anthropomorphized image of a deity. [4]

Marble map that is worshiped in place of a deity (detail), Bharat Mata Mandir (Mother India Temple), Varanasi, India, 1936 (photo: Manuel Menal, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Scholars have attributed these important shifts in Bharat Mata’s form in the 20th century to the growing confidence of the Indian national movement and to the political fissures that came to define and divide the fight for Indian independence.

By the 1940s, the Indian national movement had fractured along religious and communal lines, with prominent Muslim leaders, like Muhammad Ali Jinnah, calling for the creation of a separate homeland to safeguard India’s Muslim minority population. By 1947, these fractures resulted in the decision to partition the Indian subcontinent into not one, but two nation-states: the Republic of India, which would have a Hindu-majority population, and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, which would consist of two non-contiguous territories, each with Muslim-majority populations. Announced in June 1947 and implemented by August 1947, the partition was not easy to realize. It constituted traumatic divisions and displacements of territory, people, infrastructure, and culture, with lasting and often violent consequences across the Indian subcontinent.

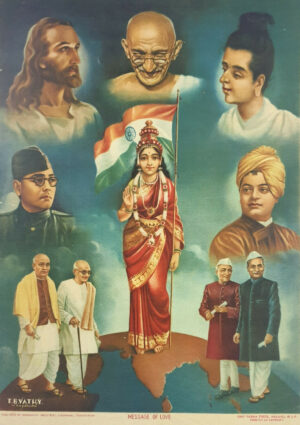

Bharat Mata’s new proximity to cartography altered perceptions of the Indian nation and its territorial reach. As Sumathi Ramaswamy has shown, Bharat Mata’s body was often harnessed by artists to extend India’s land mass, either by obscuring the location of India’s political and natural boundaries or by laying claim to contested geographic regions, such as Jammu and Kashmir. [5] T.B. Vathy’s Message of Love is, in many ways, emblematic of this artistic practice. Here, Bharat Mata sits confidently atop the globe, recalling the royal portraits of Mughal emperors and European monarchs. [6] Her feet are planted firmly at the center of the Indian subcontinent, which recedes backward into the horizon. The image is a powerful declaration of the triumph of Indian nationalism. With Bharat Mata surrounded by prominent Indian politicians and historic religious leaders, it positions India as a secular state and a new center of the world. It also suggests India’s territorial ambition by blurring the location of its new national boundaries, which in 1948, when this image was produced, were still highly contested with Pakistan due to the partition. [7]

Mother India in popular film

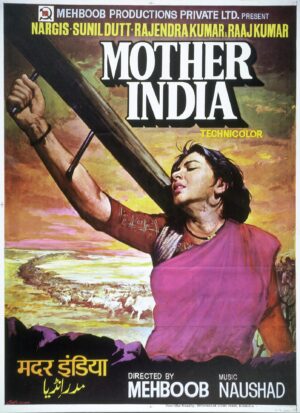

Seth Studios (designer), Mother India (1957), c. 1980s, lithograph on paper, 102 x 76 cm (Victoria & Albert Museum, London)

Following Indian and Pakistani independence in 1947, Bharat Mata maintained a prominent place within Indian popular culture. This was epitomized in 1957 by the release of Mehboob Khan’s critically acclaimed film, Mother India. The film traces the trials and triumphs of its female protagonist, a Hindu woman named Radha, who endures grave hardship and sacrifice for the well-being of her family and community. It starred famed Bollywood actress Nargis in the titular role and is widely understood to be an allegory for the struggle for Indian independence in the 20th century. [8]

A powerful exercise in nation-building, the film capitalized on the popularity of Bharat Mata iconography in both its cinematic narrative and advertising campaigns. Later movie posters, made for the film’s re-release in the 1980s, draw their design from a pivotal moment in the film where Radha persuades her fellow villagers to stay and recultivate their lands in the wake of devastating floods, which they do to great success. The posters show Radha overcome with anguish as she suffers the weight of a manual plow. This plow becomes her lifeline in this moment, a kind of third arm, as she heals her family, village, and the land. Her body, recalling the iconography and blended effects of Tagore’s Bharat Mata, is deified amid a roaring sunset wherein her sacrifice and physical suffering become seeds for the nation’s impending prosperity.

If Mother India reinforced Bharat Mata’s gendered vision for the Indian nation by linking land and prosperity to the body of the Indian woman, the film also raised important questions about the relationship between religion and citizenship in post-partition India. In this regard, the decision to cast Nargis, a Muslim actress, in the film’s title role of Radha, proved a salient choice and can be read as a provocation: Who can embody Bharat Mata? Who can belong to the Indian nation? “Can a Muslim be an Indian?” to borrow the words of Gyanendra Pandey. [9] These questions continue to energize contemporary interventions into Bharat Mata’s form and history.

Belonging to mother and nation

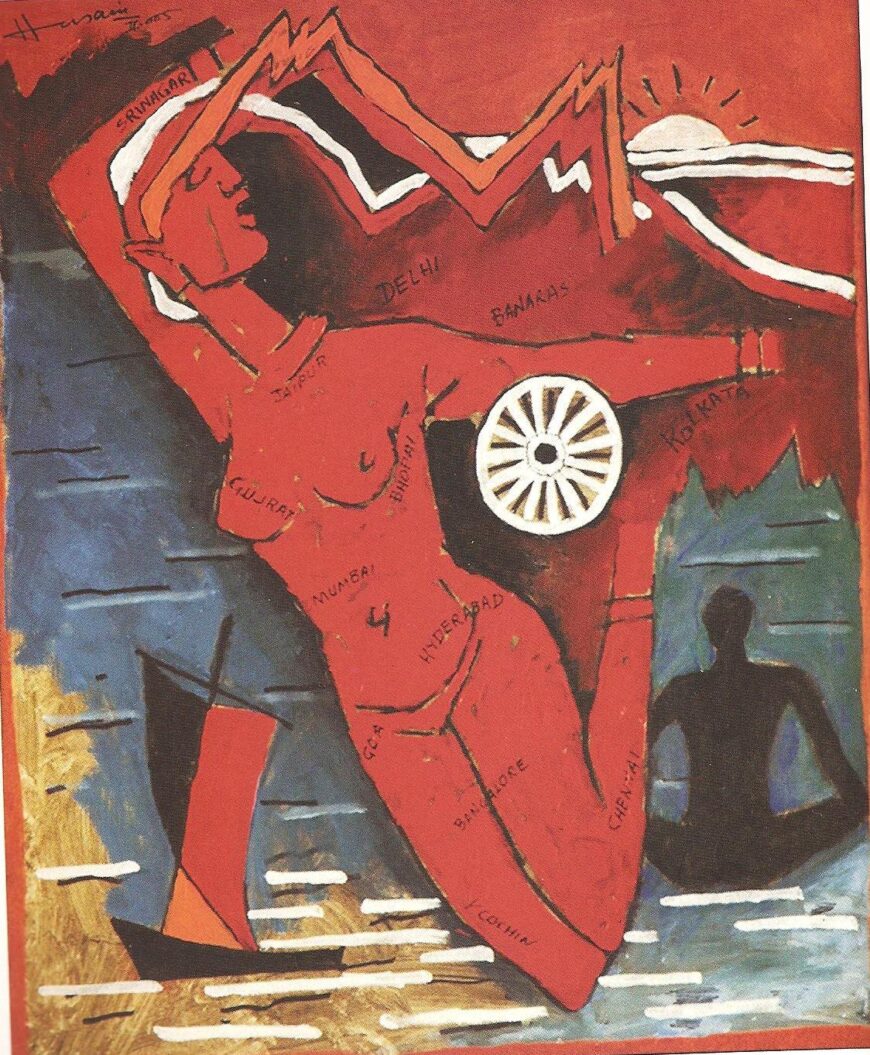

The iconography of Bharat Mata has become an important site of cultural and political contestation in South Asia. Among the most important controversies to erupt around Bharat Mata imagery in recent decades involved the pioneering modern painter M.F. Husain and his 2005 painting, Untitled, a work commonly described today as Bharat Mata.

M. F. Husain, Untitled (Bharat Mata), 2005, acrylic on canvas, 105.4 x 85.1 cm (Estate of Maqbool Fida Husain, Apparao Gallery, Chennai)

Made in acrylic, Husain’s Untitled renders the geography of the Indian subcontinent as a nude female form. This abstracted body gazes up towards the sun as her hair stretches across the Himalayas, her right arm extends into Kashmir, her left arm reaches out towards Assam, and her knees bend around the southern coast of Tamil Nadu. Her exposed form is doused in the deepest of reds, reminiscent of blood and vermillion. This body is further etched with the names of key cities and states that tattoo the folds in her skin into a familiar topography.

The painting was displayed for a short time in New Delhi in 2006, where it was exhibited as part of a charity auction. [10] During this time, it garnered intense outrage from supporters of the Hindu right, who recast the painting as a “nude goddess” and an affront to the religious sentiments of the wider Hindu majority in India. Although he was a prominent figure in the Indian art world and a founding member of the Progressive Artists’ Group, as a Muslim artist in India, Husain was also familiar with controversy. Several of his earlier nude works, which showcased the Hindu goddesses Saraswati, Sita, and Durga, had faced similar claims of obscenity as early as 1996. [11]

But unlike these earlier works, Untitled did not make explicit use of religious imagery. It was, in many ways, an overtly secular painting. It combined Husain’s concerted interest in the nude as a historic art form in South Asia with his interest in mining visual vocabularies of the nation. As art historians Sumathi Ramaswamy, Tapati Guha-Thakurta and Karin Zitzewitz have asserted, the controversy around Untitled proved quite unprecedented. It raised urgent questions about the limits of an artist’s right to freedom of expression in India and the uncertain place of the nude in modern Indian art, while also signaling a wider collapse of the secular, as both a political and artistic domain in India. [12] At stake in this rendering of Bharat Mata, moreover, became the wider availability of the Indian nation and its icons to a Muslim minority artist. [13]