Essay by Min Bora

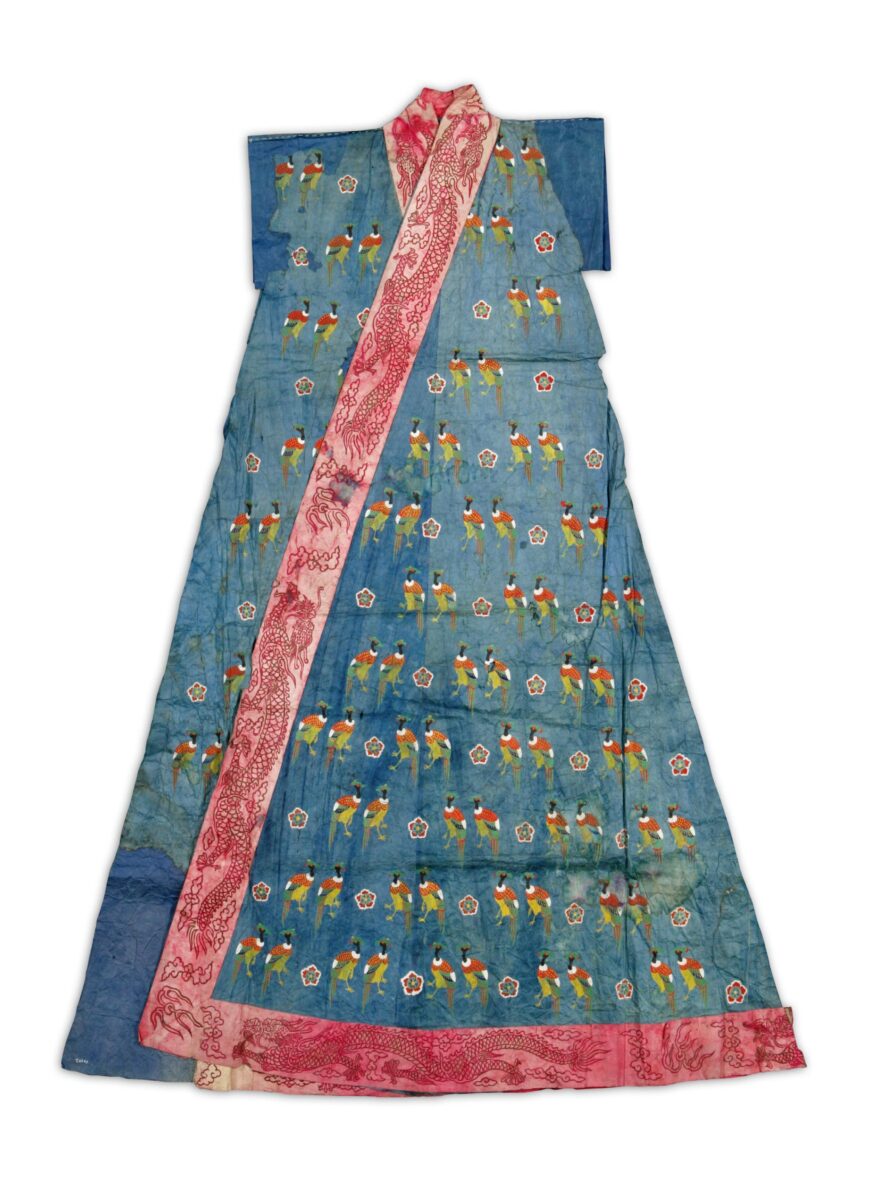

Jeogui (paper model), early 20th century, 154.5 x 28 cm, National Folklore Cultural Heritage 67 (National Museum of Korea; photo: Cultural Heritage Administration of the Republic of Korea)

A jeogui (翟衣) is an elegant ceremonial robe with a pheasant pattern, which was worn by Joseon queens on the most formal occasions. In addition to a jeogui, the queen’s formal attire also included an array of extravagant ornaments and accessories, including a jeokgwan (queen’s crown), hapi (decorative sashes), and pyeseul (an apron-like sash). In Korea, the tradition of the jeogui dates back to 1370 (nineteenth year of Goryeo’s King Gongmin), when the Goryeo Dynasty adopted the official ceremonial attire of China’s Ming Dynasty (明, 1368–1644). The jeogui legacy can be roughly divided into three phases: the early period, from the introduction of the jeogui through the fall of the Ming (1644); the middle period, when the Joseon Dynasty officially established and practiced its own jeogui system; and the late period, when the jeogui system was revised in conjunction with the founding of the Korean Empire (1897–1910). Dating from the late period, the jeogui that is housed at the National Museum of Korea is actually a paper replica that was used as a model for producing a silk jeogui. Consisting solely of the torso, without sleeves, the jeogui is painted with a pattern symbolizing the empress of the imperial court, containing twelve rows of five-colored pheasants and numerous ihwa motifs (a type of white plum blossom).

Jeogui with nine rows of pheasants, c. 1922, silk, 143.8 cm long (National Palace Museum of Korea)

History of queen’s ceremonial robe

In 1403, the Yongle Emperor of the Ming Dynasty sent Joseon an entire set of official robes for both the king and queen. After that, the Ming sent Joseon a set of official robes for the queen on fifteen separate occasions from 1405 to 1625. According to the international hierarchy of the time, Joseon was considered to be two ranks lower than the Ming. Thus, the jeogui sets that were sent by the Ming did not correspond to those of the Ming empress, but rather to those of Ming women whose husbands held the highest government posts. Those sets included crowns that were decorated with beads and seven jade-colored pheasants, red ceremonial robes with wide sleeves, vests adorned with embroidered pheasants, and decorative sashes to be worn over the robe. In 1750, after the fall of the Ming, Joseon finally established its own jeogui system. As documented in Illustrated Royal Weddings (國婚定例) and Illustrated Supplement to the Five Rites of State: Follow-up and Auxiliary Edition (國朝續五禮儀補序例), the Joseon kings wore a gujangbok robe with nine symbols, while the queens wore a jeogui with nine rows of pheasants. This standard was maintained until the end of the Joseon Dynasty.

Jeogui with twelve rows of pheasants, 1919, silk (Sejong University Museum; photo: Cultural Heritage Administration of the Republic of Korea)

In 1897, King Gojong declared the foundation of the Korean Empire, and the official attire was revised to match the elevated status of the nation. In June 1897, the state rites were revised, and then in October, Emperor Gojong ascended to the imperial throne in a ceremonial robe with twelve symbols, befitting an emperor. In accordance, the queen’s robe was also updated to include twelve rows of pheasants, rather than the previous nine.

At present, there are only three known extant examples of a silk jeogui; both the Seoul Museum of History and the National Palace Museum of Korea have a jeogui with nine rows of pheasants, while Sejong University Museum has one with twelve rows of pheasants. The jeogui at the National Palace Museum of Korea was worn in 1922 by the wife of Yeongchinwang, the last imperial prince, when the couple (who lived in Japan at the time) visited the royal court in Seoul. The jeogui from the Seoul Museum of History came from Unhyeongung Palace, but its former owner or wearer is unknown. The jeogui from Sejong University Museum once belonged to Empress Sunjeonghyo, and it was made in 1919 for the royal wedding of her son Yeongchinwang, the last imperial prince.

Left: jeogui (paper model), early 20th century, 154.5 x 28 cm, National Folklore Cultural Heritage 67 (National Museum of Korea; photo: Cultural Heritage Administration of the Republic of Korea); right: pyeseul (paper model), early 20th century, 57.2 x 32 cm, National Folklore Cultural Heritage 67 (National Museum of Korea)

Paper model of jeogui

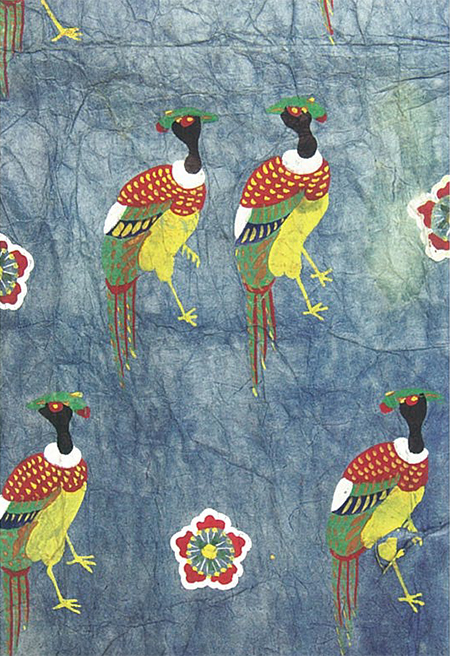

Detail showing pheasant and ihwa motifs, jeogui (paper model), early 20th century, 154.5 x 28 cm, National Folklore Cultural Heritage 67 (National Museum of Korea)

This jeogui from the National Museum of Korea is actually a paper model, produced in preparation for sewing a silk jeogui. As the only one of its kind in existence, this paper model was designated as National Folklore Cultural Heritage 67, along with a paper model for a pyeseul (an apron-like sash that hung from the front waist). Although we cannot confirm who this paper model was produced for, it is very similar to Empress Sunjeonghyo’s jeogui with twelve rows of pheasants (now housed at Sejong University Museum). The model, which consists of several pasted layers of Korean traditional paper, is almost the same size and shape as that silk jeogui, only without sleeves. Rendered against a blue background, the primary pattern consists of pairs of five-colored pheasants facing one another, with ihwa motifs in between. The robe is hemmed with red paper, decorated with a cloud and dragon design painted in gold pigment. Having twelve rows of pheasants, the jeogui paper model was made for an empress (rather than a queen).

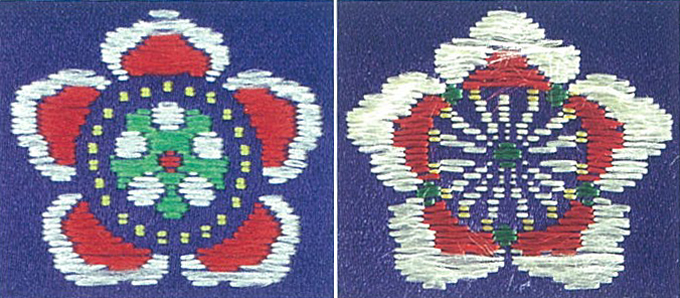

Left: ihwa flower motif from a jeogui with nine rows of pheasants (National Palace Museum of Korea); right: revised ihwa flower motif from a jeogui with twelve rows of pheasants (Sejong University Museum)

Written records refer to the ihwa motif as “小輪花,” which means “small wheel-shaped flower.” This design was likely created around 1750, when Joseon established its own jeogui system, perhaps in reference to The Collected Statutes of the Ming Dynasty (大明會典). In the two extant jeoguis at the Seoul Museum of History and National Palace Museum of Korea (both with nine rows of pheasants), the flowers have a red dot at the center, surrounded by five white dots and five petals. On the other hand, both this paper model and the jeogui from Sejong University Museum (with twelve rows of pheasants) show a revised design of the ihwa motif, with a white stamen and pistil at the center, encircled by red and white petals. This emblem became one of the primary symbols of the Korean Empire.

In most cases, Korean traditional clothes with patterns were made by first painting the motifs onto a large piece of fabric, and then cutting all of the respective parts of the garment from that single piece. In this case, however, it is estimated that the various parts of the jeogui (e.g., the sleeves, front, back, etc.) were first cut and then separately assembled in consideration of the patterns. Furthermore, unlike ordinary clothes, the pheasant pattern was pre-woven into the fabric before it was cut, indicating that the fabric was of the highest quality. This method was likely employed in order to ensure that each row of pheasants was precisely aligned across the entire robe, and that the shape of the flowers and pheasants remained consistent. As such, this paper model must have served as a reference not only for the shape of the robe, but also for the alignment of the patterns. As the only paper model of a jeogui with twelve rows of pheasants, this artifact is a crucial resource for contemporary attempts to reproduce an authentic jeogui of the Joseon era.