In 1942, the Communist revolutionary Mao Zedong boldly asserted that “There is no such thing as ‘art for art’s sake,’ art that stands above classes, art that is detached from or independent of politics.” [1] Mao, the leader of China’s Communist Party, uttered these words as he delivered lectures to fellow revolutionaries. Mao was keen to use art in service of politics—not for sophisticated urban elites, but for provincial peasants. He thought art needed to have a common, understandable style, and it should represent peasants’ lives and take inspiration from them. He also felt that art should convey the positive aspects of life under the Communists. His vision of what art should be would have a radical effect on artistic production in China in the second half of the 20th century.

Dong Xiwen, The Founding of the Nation, 1953, copied by Jin Shangyi and Zhao Yu in 1972, and modified by Yan Zhenduo and Ye Welin in 1979, oil on canvas, 230 x 402 cm (National Museum of China, Beijing)

A tumultuous period

When Mao delivered his lectures, the nation was in the midst of a tumultuous period. Communism had grown increasingly popular as the government of the Republic of China navigated conflict and war, causing enormous stress for the people of China. The ruling party of the Republic of China, the Nationalists, had been fighting the War of Resistance against the Empire of Japan, which was finally ended with the aid of the Soviet Union and the United States in 1945. War-weary and weak, the Nationalist government struggled as dissent grew among the working classes. Soon, civil war broke out between the Nationalists and the Communists, bringing an end to the Republic and hastening the rise of Communism in China.

Chairman Mao founded the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. This is the subject of Dong Xiwen’s The Founding of the Nation, first painted in 1953 on the fourth anniversary of the PRC’s foundation. It shows Mao standing atop Tiananmen (the Gate of Heavenly Peace) in Beijing, as he announces the inauguration of the PRC under red lanterns and blue skies. Several Communist officials look on, smiling in support (officials in the painting were altered or removed as those in favor shifted over time). Such transformations speak to how art primarily served as propaganda, with artists carefully highlighting the good, not the bad, all the while bending to the changing winds of politics during this chaotic time in Chinese history.

This essay introduces art created in the formative years of the PRC, when Mao’s leadership shaped nearly every aspect of Chinese culture. The years 1949 to 1966 are often described as the “Mao Era,” the early years of the PRC when a young Mao liberated China, and tapping the visual arts to convey his vision for the nation. These efforts came to a climax between 1966 and 1976, when Mao and his circle plunged the country into what is known as the “Cultural Revolution,” aiming to undo what the leadership believed to be backward-looking, feudal traditions that were preventing China from leadership in the modern world.

The Mao Era, 1949–66

The period following the establishment of the PRC in 1949—when the Communist Party came to power under the leadership of Mao Zedong, or “Chairman Mao”—is known as the Mao Era. The Communist Party took total control of art education and the lives and works of the artists themselves, and the Central Academy of Beijing became the model for regulated art schools throughout the country. Artists were called on to paint subjects (such as images of Mao, the rural peasantry, or scenes of technological progress) realistically. Even more important for the future of Chinese art was the fact that peasants and workers were initially encouraged to take up the brush and depict their own worlds. Interest shifted toward art picturing the lives of the rural masses: the soldiers, peasants, and workers—with special attention to women and others who had been excluded or sidelined in Chinese society previously. This constituted a radical break from a long established tradition in China where art was associated with the social and political elite.

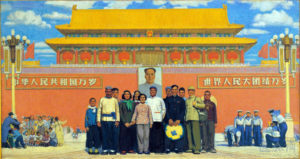

Sun Zixi, In Front of Tiananmen, 1964. oil on canvas, 153 x 294 cm. National Art Museum of China, Beijing.

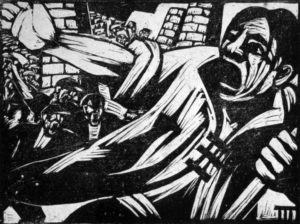

The Party sought to highlight the promise of this new era and consequently shifted away from darker, heavily-inked portrayals made earlier, such as the revolutionary woodcuts of Hu Yichuan. Instead, artists portrayed colorful scenes that are light-filled or have white backgrounds, with simple forms and lines, such as Sun Zixi’s oil painting, In Front of Tiananmen. Smiling onlookers are displayed outside of Tiananmen, the Gate of Heavenly Peace, as if poised for photographs while sightseeing in Beijing. It is not an image of revolution, as seen in To the Front!, but rather an image of happy times under bright blue skies, with sunshine reflecting off the faces of the people. The central group of men, women, and children stand beneath a portrait of Mao, many wearing uniforms to identify their occupations. Behind them to the left, a photographer appears to lean over his equipment, arranging a group dressed in multi-ethnic clothing. On the right, a group of uniformed students prepare to take a snapshot of themselves. Simple and easy to understand, the large-scale composition was created with an outline and flat-color method. It is typical of socialist realism, a realistic style of art developed in the Soviet Union to glorify communist ideals, here adapted to China through the depiction of people and places of the PRC. Painted on the fifteenth anniversary of the nation, In Front of Tiananmen portrays the leisure activities of ordinary men and women, as well as their pride in a new China.

Traditional painters under Mao

While China’s academies were shifting toward socialist realism, they were also reinvestigating traditional artistic modes. Many styles that had flourished during the Republic of China up to the 1930s were reformed or eradicated under Mao. These included works considered modern (due to their use of formal abstraction), as well as those appearing traditional (such as gouhua). Guohua (literally meaning “national painting”) describes paintings created in the traditional medium of brush and ink, such as handscrolls or hanging scrolls on paper or silk. This traditional medium had both scholarly and courtly associations (as ink painting required years of training in brushwork and calligraphy to which most common people would not have had access).

Fu Baoshi and Guan Shanyue, Such is the Beauty of Our Rivers and Mountains, 1959, Great Hall of the People, Beijing (photo: Gisling, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Cultural leaders were divided as to whether or not guohua could be adapted to revolutionary needs. The vast majority of guohua painters were given financial security and status by membership in the provincial painting academies and in the local branches of the Artists’ Association, which was controlled by the Ministry of Culture. Despite this, their work was limited to preferred subjects and styles.

While established artists like Qi Baishi, Liu Haisu, and Huang Binhong were left to go on painting in their own way, masters of the next generation were under great pressure to dedicate their art to the revolution by painting images of reconstruction, dam building, and peasant life, or even illustrating a line from poems written by Mao. For instance, the guohua artist Fu Baoshi was given a number of important commissions, most notably the iconic landscape painting, Such is the Beauty of Our Rivers and Mountains, a collaboration with Guan Shanyue that adorns the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. Painted on a grand scale, this painting illustrates a line from one of Mao’s poems, called “Snow” in which he describes gazing over the northern landscape. The painting’s title is drawn from a line the poem and became a slogan for mapping China’s territory through art providing guohua artists with a political justification for reinventing the tradition of Chinese landscape painting. With a blazing red sun rising over the mountainous terrain, Fu Baoshi transformed the landscape into a bold statement of national pride under Communist leadership—the land that Mao reclaimed for the people of China.

Pan Tianshou, Red Lotus, 1963, ink and color on paper (hanging scroll), 161.5 x 99 cm (Pan Tianshou Memorial, Hangzhou)

Other artists, like Pan Tianshou, were also under great pressure to steer their ink painting to communist themes and styles. In Red Lotus, a lotus flower rises from murky waters. However, the flower is not pictured in its typical, natural hue of pale pink, but in a deep, crimson red that echoes the red sun rising over the northern landscape in Fu Baoshi and Guan Shanyue’s mural. Blood-red crimson, a subtle repurposing of the vermilion red that signified the bygone imperial era.

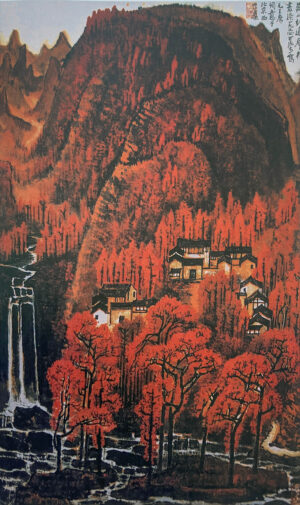

Li Keran, Ten Thousand Crimson Hills, 1964, hanging scroll, ink and color on paper (collection of the artist’s family, Beijing)

By the 1960s, guohua artists were in a more precarious position. In Li Keran’s Ten Thousand Crimson Hills, painted in 1964, red-stained mountains in a densely packed composition appear ominous. Although Li painted this work in the same year as Sun Zixi’s In Front of Tiananmen, the emotional intensity of his ink painting seems to be the opposite of the bright and optimistic mood that characterizes socialist realism. Several major crises of the late 1950s might explain the new approaches of artists like Li and Sun.

In the Hundred Flowers Movement, Mao seemingly invited criticism of the Party through the slogan, “Let a hundred flowers bloom, let a hundred schools of thought contend.” Many intellectuals took him at his word and urged a gradual transformation of the Party’s hardline policies that had alienated the intelligentsia. In response, Mao ruined the lives of more than 300,000 people who had spoken out, sending a clear message of conformity to everyone—especially artists. Soon after, Mao’s Great Leap Forward became a large-scale disaster. The Great Leap Forward was an economic and social plan intended to transform China into a modern, industrialized society but ended in famine and widespread suffering. It was thought that by melting down all available metal in “backyard furnaces,” China would produce the steel needed to modernize and compete with the rest of the world. Unfortunately, the idea resulted in widespread death and famine, since peasants were diverted from the fields and melted down farm implements and tools they needed for agriculture. Through the two years of bad harvests that ensued, it is estimated that over 20 million Chinese died. These events were not depicted in art.

Emerging from the crises of this period, and with the Cultural Revolution looming, guohua painters like Fu Baoshi, Pan Tianshou, and Li Keran faced the difficult decision of how to picture their world.

The Cultural Revolution, 1966–76

By the late 1960s, state-sponsored art continued to present views of happy and productive peasants, though it intensified during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, or “Cultural Revolution” for short. This was Mao’s effort to regain his political hold after the disasters in the 1950s (the Hundred Flowers Movement and Great Leap Forward). The Cultural Revolution called for attacks on the “four olds”—customs, habits, culture, and thinking. Radicalized youth called the Red Guards attacked the existing order in an effort to destroy the ways of the past—everything that had previously been respected, from schools to society. The Red Guards destroyed countless cultural monuments, everything from temples to artworks, in their quest to rid China of its feudal heritage.

A still from the ballet, Red Detachment of Women, with soldiers of the Women’s Detachment performing rifle drill in Act II, from the 1972 National Ballet of China production (photo: White House photo by Byron Schumaker, CC0)

The Cultural Revolution devolved into a period of widespread chaos. Few artworks survived this turbulent decade, though artists strove to advance Communist interests through revolutionary topics and propaganda. Mao’s last wife, a former Shanghai movie actress named Jiang Qing, became a leading authority in the arts and a key figure politically. She was the leader of the Gang of Four, a political faction of four powerful Communist Party officials who played a key role in Chinese arts and culture during the Cultural Revolution. Notably, Jiang singled out specific art, including the performing arts, as models of Maoist ideology; for instance, she supported a model ballet called Red Detachment of Women that premiered in 1964.

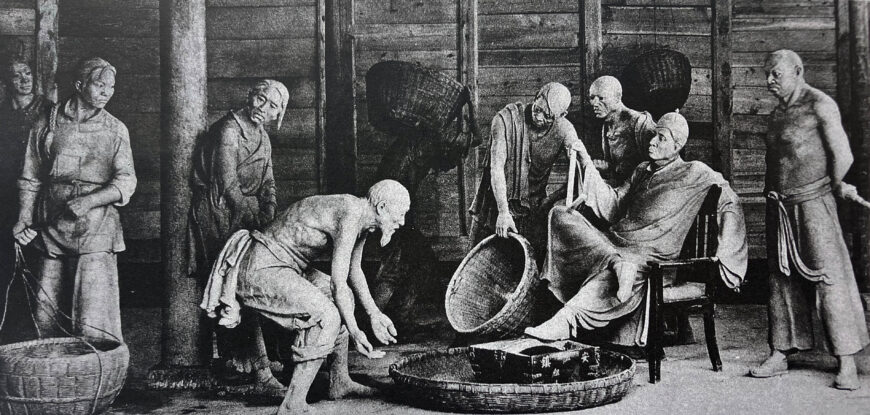

Rent Collection Courtyard (detail), 1965, clay, Dayi County, Sichuan, from Rent Collection Courtyard: Sculptures of Oppression and Revolt, 2nd ed. (Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 1970), n.p.

One of the most famous artworks that she supported is the life-size terracotta tableau, Rent Collection Courtyard. The site-specific installation depicted the alleged brutality of a Sichuanese landlord, using 114 life-size clay figures to portray the evils of the oppressing class before liberation. Six scenes picture impoverished peasants delivering baskets of grain as payment to their landlord, who sits idly, and it concludes with a scene of class struggle. A prime example of socialist realism, the work was duplicated and placed in numerous cities—a fiberglass set even traveled abroad to several international locations.

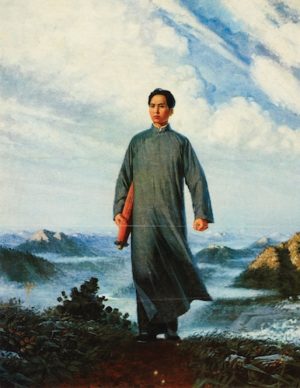

The Communist Party also commissioned numerous portrayals of Mao to further propel the Cultural Revolution. Although the Central Propaganda Department had standardized portraits of Mao since the founding of the PRC, representations of Mao became even more idealized during this decade. Known as “Mao paintings,” works such as Liu Chunhua’s Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan portrays a young Mao surrounded by a luminescence that seems to radiate from his body—he appears superhuman, extraordinary—and by extension capable of leading the country. Portraits like this one typically use warm tones and smooth brushwork, once again drawing on socialist realism.

Chen Yanning, Chairman Mao Inspects the Guangdong Countryside, 1972, oil on canvas, 172.5 × 294.5 cm (The Long Museum)

Other Mao paintings, such as Chen Yanning’s Chairman Mao Inspects the Guangdong Countryside, depict specific historical moments. Here, Chen shows Mao’s highly publicized visit to Guangzhou (a southern province of mainland China) at the height of the Great Leap Forward in 1958. Recall that even though the Great Leap Forward was intended to transform China into a modern, industrialized society, it ended in widespread chaos and suffering. Chen modeled Mao’s visit after centuries of inspection tours that Chinese emperors historically undertook to solidify local support for their reign. Chen’s idealized portrayal pictures Mao as a saintly icon, dressed in a light-colored, western-style shirt and belted pants in the Western style, but carrying a woven sunhat as he strides along in solidarity with the dirty but smiling, barefooted masses. The lush and verdant land, punctuated by lines of electricity, suggests that Mao’s plan to modernize had been successful—though it was not. Chen’s painting was reproduced in numerous posters and copies, an uplifting image belying the fact that this was a tragic time for many people.

Traditional painters during the Cultural Revolution

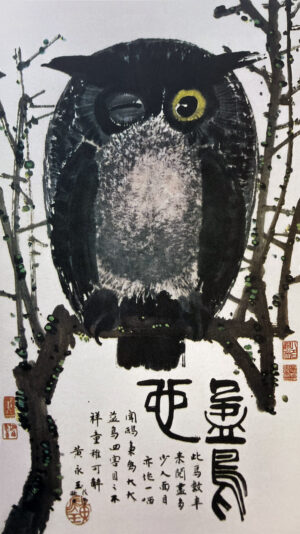

How did traditional ink painters (gouhua artists) fare in the Cultural Revolution? Many artists and intellectuals, including those who had held prominent posts at art institutions, were sent to reform camps and faced persecution. Some presented alternative narratives to that of the Communist Party through seemingly innocuous subjects such as Winking Owl, painted by the woodblock designer Huang Yongyu in 1973. Huang’s portrayal of the ominous bird, pictured frontally with one eye open and one closed, appears to be engaged in a secret communication with the viewer. It perplexed Party officials (and has continued to perplex art historians!). The work was publicly exhibited the following year at the Black Painting Exhibition in Beijing, which included 188 works believed to be subversive. Although Jiang Qing condemned the work, Huang was eventually exonerated by Chairman Mao himself in the waning years of the Cultural Revolution with his observation that owls do, in fact, tend to close one eye at a time—thus quieting for a moment the political frenzy around visual imagery.

From Liberation in 1949 to the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, Chinese artists adapted their art to rapidly shifting political circumstances. Some embraced oil painting and sculpture in the mode of Soviet-style socialist realism. Others conformed to Mao’s agenda by modifying the subjects and styles of ink painting, forging a path known as the “new guohua.” Many artists fled the country or suffered persecution, hastening an end to this transformative moment in Chinese history.

Notes:

[1] 为艺术的艺术,超阶级的艺术,和政治并行或互相独立的艺术,实际上是不存在的。Mao Zedong, Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art, May 1942.

Additional resources

Melissa Chiu and Zheng Shengtian, Art and China’s Revolution (New York: Asia Society, 2008).

Elizabeth J. Perry, Anyuan Mining China’s Revolutionary Tradition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012).