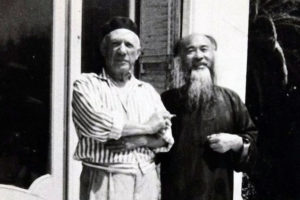

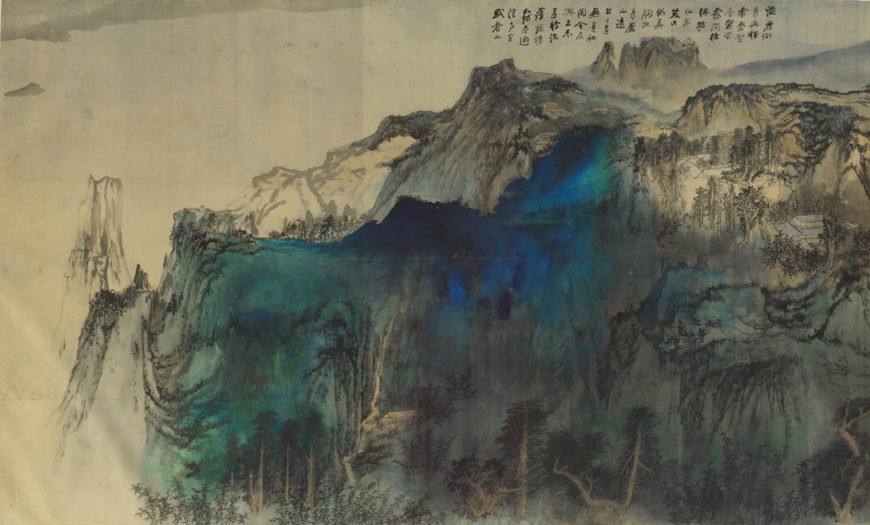

Zhang Daqian, Panorama of Mount Lu, 1981–83, wall mural in portable scroll format, ink, color on silk, 178.5 x 994.6 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

Panorama of Mount Lu is a spectacular landscape of ink and color by the Chinese modernist, Zhang Daqian (also written as Chang Dai-chien, as preferred in Taiwan). The ethereal composition pulsates in hues of blue and green, with black veins of ink shaping expansive vistas and plummeting ravines. Clouds and mists in pools of ink define the first section from the right, summoning the viewer toward mountain peaks before soaring over treetops and a temple in the central section. In the final section, the mountains plunge to a lake and expansive vista, concluding a visual journey in three main sections. Though spanning the wall like a mural, this 32 feet long painting is in the tradition of the handscroll, and was composed on a table like any other Chinese ink painting.

Painting Table, late 16th century–early 17th century (Ming dynasty), China (The Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

However, due to its tremendous scale, the elderly master, Zhang Daqian, was required, at times, to paint upside down. Zhang had never visited Mount Lu, which is in southeastern China, nor had he painted the subject throughout his long career. Free to imagine this site, Zhang composed Panorama of Mount Lu as a personal testament to his mastery of Chinese ink painting while challenging concepts of abstract expressionism that he frequently encountered in his travels abroad. Rather than adopt modern approaches popular in the United States or Europe, Zhang credited ancient Chinese painting as the inspiration for his work.

Zhang Daqian, Panorama of Mount Lu (detail), 1981–83, wall mural in portable scroll format, ink, color on silk, 178.5 x 994.6 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

A modern blue-green landscape

Mural of King Sivi from the north wall of Mogao Cave 254, Dunhuang, 439–534 C.E. (Northern Wei Dynasty) (photo: Courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

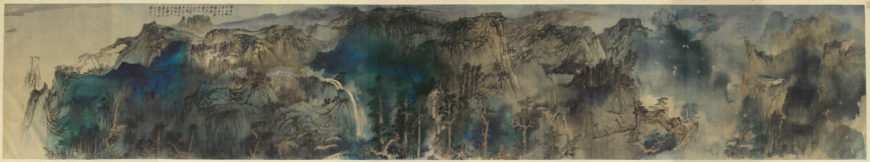

In Panorama of Mount Lu, Zhang drew on the blue-green landscape mode, in which artists traditionally used vibrant blue-green hues to characterize landscapes as otherworldly paradises as early as the Tang dynasty. The mineral pigments of green malachite and blue azurite entered China along the Silk Roads, where they adorned the murals of the Mogao caves at Dunhuang as well as paintings on silk created for the imperial court. In fact, Zhang spent two years in Dunhuang, studying and copying its murals early in his life. These vibrant blue-green hues are not intended to resemble landscapes on earth—they appear abstract, and so painters often used them to suggest the lands of Daoist immortals or the Western Paradise of the Buddha.

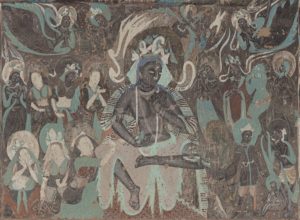

Emperor Minghuang’s Journey to Shu, c. 618–907 C.E. (Tang dynasty), hanging scroll, 247 x 92.6 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

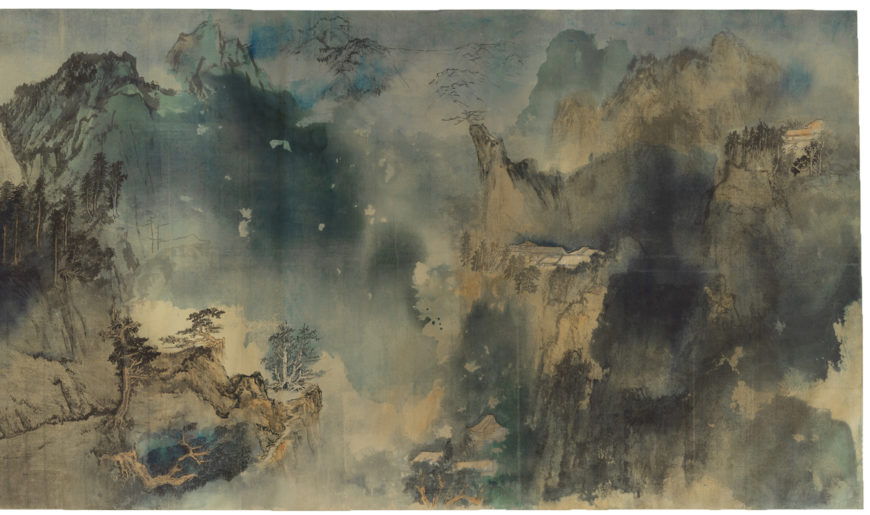

Consequently, the blue-green mode became closely associated with early landscape paintings, such as the iconic Emperor Minghuang’s Journey into Shu, which pictures the dramatic end to the Tang dynasty. Later artists, including Zhang, came to use this landscape mode for its archaizing quality, or one characterized by the use of ancient or medieval stylistic features.

Zhang Daqian, Panorama of Mount Lu (detail on the far left), 1981–83, wall mural in portable scroll format, ink, color on silk, 178.5 x 994.6 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

Zhang Daqian, Peach Blossom Spring, 1982, hanging scroll, ink and color on paper, 209.1 x 92.4 cm (Long Museum, Shanghai)

Zhang similarly characterized Mount Lu as an ethereal, spiritual realm inspired by a site in his native mainland China, visualized as a blue-green landscape. However, rather than employ a detailed application of mineral pigments, Zhang used rich, ink texture strokes, controlled washes of ink and color, and a novel technique of “splashed ink” (pomo) that blurred the blue and green hues with heavy applications of water. Although Zhang did not view this innovation as abstraction—at least not in the sense of abstract expressionism—he did forge a modern, avant-garde approach to Chinese art, as we see in Panorama of Mount Lu. Rather than rely upon the quality of lines of ink for expression, which are regarded as the backbone of Chinese painting, Zhang explored the principles of water and color.

Panorama of Mount Lu was not Zhang’s only work to demonstrate the splashed-ink technique. In his six-and-a-half-foot tall painting, Peach Blossom Spring, touches of pink complement a vast blue-green ravine—legendary blossoms that lead to a utopian paradise, as described by the ancient Chinese poet Tao Yuanming. Although the recent record-breaking sale of Peach Blossom Spring for nearly 35 million dollars in 2016 has attracted international attention, the contemporaneous Panorama of Mount Lu is even more ambitious in its scale. Surpassing the Peach Blossom Spring in width at over five feet tall and thirty-two feet long, Zhang required a table be constructed to meet its enormous dimensions and then modified his Taipei studio to accommodate the table. Unlike European easels that hold canvases stretched on wooden frames, Chinese ink paintings are composed on flat surfaces. As a further challenge, Zhang’s patron selected a seamless silk panel with a sized surface to better absorb the ink and color, rather than paper. Works typically would be unrolled and “read” from right to left, as in Panorama of Mount Lu, however the enormous dimensions and intended location for this work meant that the entire composition would be visible at once instead of being slowly unfurled like a scroll.

The medium of ink and color on paper is typical of guohua, or “national painting,” a term that people used to describe Chinese ink painting in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The term guohua, rather than wenren hua (literati painting) or simply shuimo hua (water-and-ink painting), emphasized the Chinese origins of this art form while avoiding the elitist association with the literati (the educated elite). The literati, scholar-amateurs who held positions in the imperial bureaucracy (although also professional painters who worked in this mode) often painted for their friends and for personal self-cultivation. Their skilled use of the brush allowed for expressive qualities through variations in water and ink, furthered by highly absorbent paper rather than the relatively unforgiving surfaces of silk.

Zhang Daqian, Panorama of Mount Lu (detail on the far left), 1981–83, wall mural in portable scroll format, ink, color on silk, 178.5 x 994.6 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

Zhang elevated each of these formal principles of scale in Panorama of Mount Lu, forming a modern aesthetic that blurred the boundaries between traditional assumptions of literati and professional painters. Although these distinctions had been outdated for hundreds of years in Chinese art, they nonetheless pointed to concerns for the social functions of art (traditionally the preference of literati, who often painted for personal uses) and its commercialization (with patrons commissioning art, or artists selling their work in an art market). Due to the resources required for such a composition and the public nature of large-scale paintings, works like Panorama of Mount Lu are more commonly associated with professional painters, regardless of its expressive brushwork. Scholars and other amateurs who painted for self-cultivation and social occasions often favored the more private formats of handscrolls and album leaves less favorable for a more public display. Merging both impulses, Zhang completed the work in Taipei as a commissioned gift for a friend named Li Haitian who had opened a Holiday Inn in Yokohama, Japan, where the work was to be displayed as a wall mural. Nevertheless, the work remained with Zhang’s family and now resides in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, beside Zhang’s former studio.

International celebrity

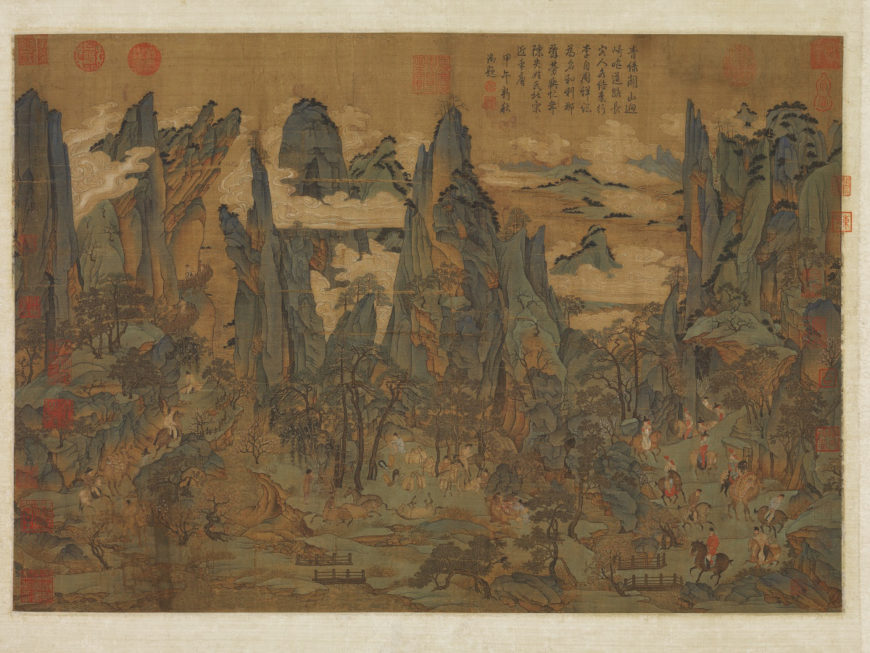

Much of Zhang’s success as an artist stemmed from the allure of his character and biography, which were especially unusual given his historical circumstances. Born in the interior province of Sichuan, Zhang traveled widely throughout his life, which allowed him to continue his growth as an artist while many could not. When the Chinese Communist Party came to power in 1949, he traveled to Japan and Europe, and established residences in Brazil, then Big Sur in California, and finally Taiwan, escaping the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. A tremendously skilled, and at times mischievous personality, Zhang became an internationally acclaimed modernist for works such as Panorama of Mount Lu, which demonstrated a rethinking of the expressive principles, medium, format, and social uses of Chinese ink painting. He was a celebrity, an artist whose gown and long beard conveyed the aura of an ancient scholar, much to the delight of the press and many friends who arranged for his travels around the world.

Zhang’s abilities as an artist drew heavily on the practice of connoisseurship; the close analysis of the formal features and provenance of artworks. In fact, upon attending a 1956 exhibition of his work in France, Zhang visited Picasso and the two became friends, reportedly comparing works and testing one another on forgeries.

Zhang Daqian, stone seal with inscription “qian qian qian,” seal, 20th century, jade, 4 x 3.9 x 4.6 cm, Republic of China. Left: the seal; center: the bottom of the seal; right: the seal as it looks stamped on paper (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

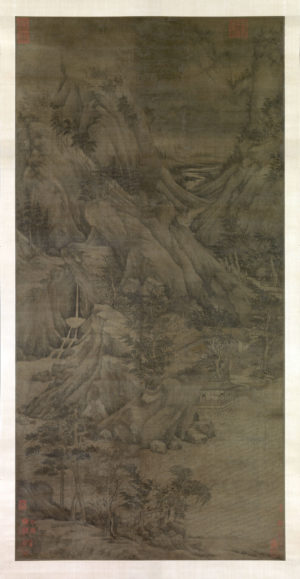

Attributed to Dong Yuan (active 930s–60s), Riverbank, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, 220.3 × 109.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

It is believed that Zhang painted over 30,000 works in his lifetime, about 5,000 of which survive today. In addition to copying the murals in Dunhuang, he studied the materials, brushwork, subjects, styles, and even the personal seals of painters from past to present. It is expected that Chinese painters learned by copying ancient masters, following the principles of the sixth-century theorist, Xie He.

Capable of making virtually identical copies of ancient works, Zhang still emphasized personal expression and the creative process. However, Zhang went a step further by carving his own seals, occasionally in the likeness of other masters, and meticulously researched signatures and biographical accounts of the ancients in records that art historians use to determine provenance. He often collected early works, at times embellishing them with reference to contemporary records or attending to the material qualities of ancient materials. Consequently, many works that have passed through his hands have become controversies, most notably the painting Riverbank, which several experts now believe to be a partial or full forgery by Zhang. One can argue that Panorama of Mount Lu benefited from a lifetime of studies, copies, and forgeries and marked a new era in ink painting.

Zhang painted throughout some of the most turbulent periods of China’s history, from the Republican era through the People’s Republic of China in 1949, all the while heightening the appeal of Chinese ink painting to a modern, international audience. For its spectacular technical mastery of ink and color, and global relevance as a grand-scale abstract composition, Panorama of Mount Lu stands as a monument to Zhang’s legacy.

Additional resources

Shen C. Y. Fu, Challenging the Past: The Paintings of Chang Dai-chien. Washington, D.C.: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institute in association with University of Washington Press, Seattle and London, 1991.

Abode of Illusion: The Life and Art of Chang Dai-chien. Directed by Carma Hinton and Richard Gordon. Distributed by Direct Cinema Limited, 1993.

Smith, Judith G., and Wen C. Fong, Issues of Authenticity in Chinese Painting. Edited by Judith G. Smith and Wen C. Fong. New York: Dept. of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013.