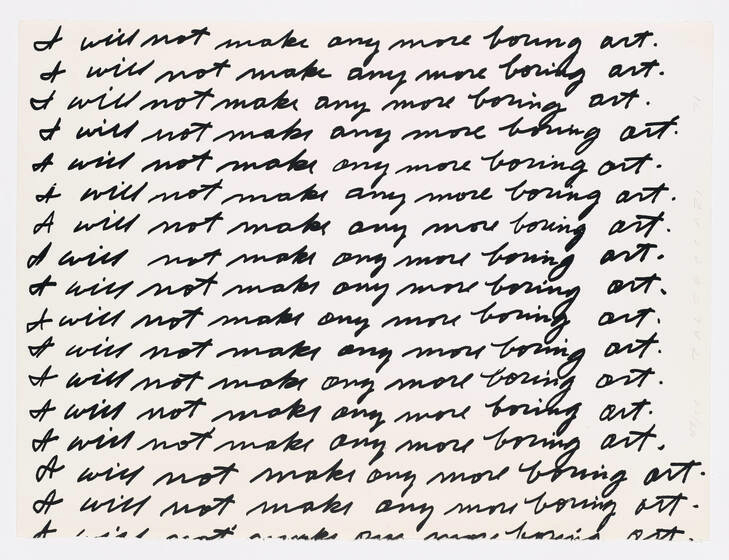

Baldessari adopts a familiar school-room punishment as a promise to himself.

John Baldessari, I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art, 1971, lithograph, 57 x 76.4 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York), images © John Baldessari, courtesy of the artist. Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

John Baldessari, I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art, 1971, lithograph, 57.3 x 76.5 cm (Whitney Museum of American Art) © John Baldessari, courtesy of the artist

Serious humor

“I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art,” repeated in a neat cursive script down the length of a sheet of lined paper is clearly reminiscent of an old-fashioned school-room punishment. But just who is it that the artist, John Baldessari, is punishing? The lines are stark and simple, and like so much of John Baldessari’s art, employs a wry humor that turns on the art world, only in this case, the blackboard is a canvas.

Only a year earlier, in 1970, Baldessari underlined a key rupture in his career and one that was taking place in the art world as well at that time. Since the 1950s, Abstract Expressionism had been the dominant avant-garde style in galleries and art schools. For example, Jackson Pollock’s huge canvases, dense with paint he applied directly, were understood (however inaccurately) to be a direct expression of his internal emotional state.

Cremation project

As a young artist, Baldessari had also painted abstractions. But in 1970, a year before I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art, Baldessari, together with friends and students from University of California at San Diego, gathered paintings he had made as a young artist and drove them to a crematorium where they burned them. The artist then placed the ashes into an urn with a bronze plaque inscribed,

JOHN ANTHONY BALDESSARI

MAY 1953 MARCH 1966

The urn and plaque, together with documenting photographs of the cremation constitute Baldessari’s Cremation Project, 1970. The previous year, the artist had written of this project as an act to,

…rid my life of accumulated art….It is a reductive, recycling piece. I consider all these paintings a body of work in the real sense of the word. Will I save my life by losing it? Will a Phoenix arise from the ashes? Will the paintings having become dust become materials again? I don’t know, but I feel better.

[1]In Cremation Project, Baldessari defined the clearest possible demarcation between his early and mature work. By sacrificing his early paintings, by burning them, he emphasized their physicality. They existed as a thing in the world that could be destroyed. But he shifts our frame of reference from the physical, the material, by creating a work of art that relied on the physical artifact, the ashes and urn, only as a way to draw the viewer to the larger conceptual issues—including the construction of a division in his career.

With the Cremation Project, John Baldessari staked his place in the highly intellectualized space of the 1960s and 70s conceptual art practice. By 1970, Conceptual art had established a place for itself in the art world. The stark machined repetitions created by the artist Donald Judd and the grids painted by Agnes Martin laid the groundwork for artists like Sol Lewitt who created written instructions for lines drawn with mathematical precision onto a wall to create dazzling geometries. Lewitt had created conceptual works of art that asked the Platonic question, where is the art itself actually located? Does it exist as the completed drawing on the wall? Does it exist in the originary act of writing the instructions? Is the art embedded in the performance of the work when assistants do the drawing? What happens when the wall drawing is painted over and is remade somewhere else? This was the world of ideas into which Baldessari entered.

Word paintings

In Baldessari’s art, words, photographs and paint offer visual statements that are so flat, so bald-faced in their directness and sincerity that they become ironic visual statements aimed at the very definition of what art is. And because these statements are on canvas or within a galley context, they challenge the most sacred theories of modern art, what the artist calls “received wisdom.”

Baldessari’s word paintings of the late 1960s and early 1970s are a case in point. Many were hand-lettered onto stretched canvas by sign painters that Baldessari had hired to render statements that he had not even written but had only read. These are often statements that naively set out to define the most elusive of questions that confront artists. And they are rendered in the clearest most direct lettering possible, the lettering found on a sign, the most earnest typography that directs and informs in the most straightforward manner possible. We cannot help but trust what these sign paintings tell us, even when Baldessari’s word paintings offer audaciously innocent solutions to the complex theory-soaked issues that define modernism.

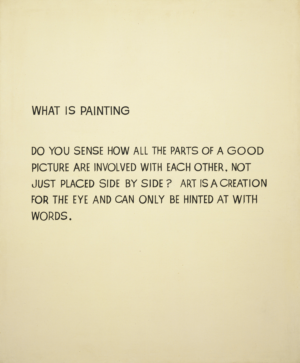

Works of art such as What is Painting, 1966–68, Everything is purged from this painting but art, no ideas have entered this work, 1966–68 and Composing on a Canvas, 1966–68 are brilliantly ambitious. They layer the false objectivity of didactic grammar and clear careful hand lettering over impossibly trite yet seductive solutions at the very core of art’s definition.

John Baldessari, What is Painting, 1966–68, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 172.1 x 144.1 cm (The Museum of Modern Art)

For example, What is Painting tries to define what painting is and does so in only three short sentences. But these sentences are written on a canvas and so inherit a fraught five hundred year history of art making. What makes these issues all the more pleasantly absurd is that Baldessari is at least as well known for his long career as a teacher as he is as an artist. So when he offers paintings with statements such as, “Everything is purged from this painting but art, no ideas have entered this work,” the allegedly instructive nature is given more weight and is ultimately more absurd.

Nova Scotia College of Art and Design

Soon after the Cremation Project, Baldessari was asked by the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design to exhibit his work there. Instead of sending art, Baldessari sent instructions to the school in the form of a letter for the initial iteration of I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art, a work based on a sentence Baldessari had written to himself in a notebook he then kept. The letter reads in part,

. . . I have no idea what your gallery looks like of course, and I know that you do not have much money for shows so that conditions my ideas of course. . . . I’ve got a punishment piece. It will require a surrogate or surrogates since I cannot be there to . . . impose punishment. But that’s ok, since the theory is that punishment should be instructive for others. And there is a precedent for it, Christ being punished for our sins, and many others. So some student scapegoats are necessary. If you can’t induce anybody to be sacrificial and take my sins upon their shoulders, then use whatever funds there are, fifty dollars, to pay someone as a mercenary.

The piece is this, from floor to ceiling should be written by one or more people, one sentence under another, the following statement: I will not make any more bad art.

At least one column of the sentence should be done floor to ceiling before the exhibit opens and the writing of the sentence should continue everyday, if possible, for the length of the exhibit. I would appreciate it if you could tell me how many times the sentence has been written after the exhibit closes. It should be hand written, clearly written with correct spelling. . . .

[2]By the end of the exhibit the walls were covered with Baldessari’s statement of sacrificial punishment and he allowed the school to create a lithograph of the work for their fundraising based on his own handwriting.

A strategist

Baldessari has called himself “purely a strategist” and in I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art he references the fundamental modernist tension between the word and image that Magritte had exposed in The Treachery of Images and the cool, spare, self-referential repetitions of the minimalists. John Baldessari has spent his career coaxing beauty and complexity from our prosaic visual culture.

Special thanks to Sandy Heller, The Heller Group, LLC.