“Colombian artist Doris Salcedo discusses why she split the turbine hall floor. Her new work, Shibboleth, is a long snaking fissure that ran the vast length of the Turbine Hall, as if striking to the very foundations of the museum. Something similar might be said of the concept that underpins the piece. The word ‘shibboleth’ refers back to an incident in the Bible, which describes how the Ephraimites, attempting to flee across the river Jordan, were stopped by their enemies, the Gileadites. As their dialect did not include a ‘sh’ sound, those who could not say the word ‘shibboleth’ were captured and executed. A shibboleth is therefore a token of power: the power to judge, reject and kill. What might it mean to refer to such violence in a museum of modern art? For Salcedo, the crack represents a history of racism, running parallel to the history of modernity; a stand off between rich and poor, northern and southern hemispheres. She invites us to look down into it, and to confront discomforting truths about our world.” (Shibboleth: TateShots; Tate Modern, London)

Doris Salcedo, Shibboleth, 2007–08, installation (Tate Modern, London; photo: Nuno Nogueira, CC BY-SA 2.5) © Doris Salcedo

The Turbine Hall

Since 2000, the Tate Modern has commissioned installations (the Unilever series) for the museum’s enormous Turbine Hall, including Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project (2003) and Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds (2010). In the eighth iteration, the Colombian artist Doris Salcedo produced Shibboleth, a deep meandering crack in the floor. Despite the unassuming nature of this work, it defies neat description and exists in a limbo between sculpture and installation, and the provocative title complicates the work instead of decoding it.

Salcedo has offered few explanations beyond stating how the fissure represents the immigrant experience in Europe. Though this theme is apparent in the work, it is by no means the only issue raised. As photographs of the installation demonstrate, visitors contorted their bodies in infinite ways as they tried to see below the crack. In Shibboleth, Salcedo elaborates a complex socio-political topic in a work with a tremendous formal presence.

Coded identification

Salcedo’s installation requires attentive viewing. The rupture measures 548 feet in length but its width and depth vary (changing from a slight opening to one several inches wide and up to two feet in depth). The viewer’s perception into the crevice alters, as he or she walks and shifts to better glimpse inside the cracks and appreciate the interior space, notably the wire mesh embedded along the sides.

Doris Salcedo, Shibboleth, 2007–08, installation (Tate Modern, London; photo: Chris Geatch, CC BY-SA 2.0) © Doris Salcedo

Change in perspective is one of Salcedo’s goals. To go from viewing this installation as a fissure in concrete to an artwork about the disenfranchised may seem like a big step. It is helpful to think of Shibboleth as a work of conceptual art since the ideas that frame the physical crack in the floor are of equal, if not greater importance than the material work itself. Salcedo’s installation at the Tate Modern would be completely different if it were simply untitled; indeed, the analysis of the work would then settle exclusively on its formal qualities. But Salcedo has bestowed a curious and specific name: “Shibboleth,” a codeword that distinguishes people who belong from those who do not.

Doris Salcedo, Shibboleth, 2007–08, installation (Tate Modern, London; photo: Nic McPhee, CC BY-SA 2.0) © Doris Salcedo

Every community, culture, and nation has its shibboleth. Among the U.S. military, “lollapalooza” was used during World War II since its tricky pronunciation could identify native, English-speaking Americans. But the sinister history of the word “shibboleth” illustrates how friends and enemies are separated by fine, linguistic lines. Any stranger in a foreign land appreciates the vulnerability this entails, especially the fear of being outed as a foreigner and exposed in a hostile environment.

Doris Salcedo, Noviembre 6 y 7 (November 6 and 7), 2002, 280 wooden chairs and rope (Palace of Justice, Bogotá; photo: Sergio Clavijo) © Doris Salcedo

Irrevocably “other”

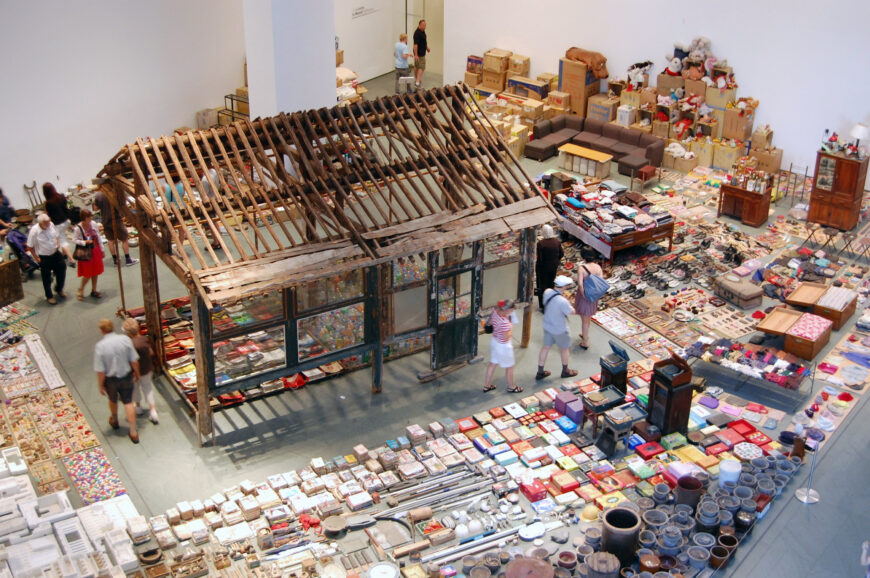

Salcedo’s experience as a Colombian artist working abroad has made her especially sympathetic to the plight of marginalized people. Between 2002 and 2003, Salcedo completed two installations that make this clear. In the first work, the artist staged a performance where she lowered empty wooden chairs over the side of the Palace of Justice in Bogotá. The performance lasted 53 hours and commemorated the 1985 siege in that building where three hundred people were held hostage; the siege ended in a bloody confrontation between rebels and the military.

The second installation also honored the victims of senseless violence. Salcedo piled more than 1,500 chairs into a space between two buildings in Istanbul. The breathtaking sight of this nearly three-story sculpture highlighted how warfare disrupts everyday life and creates refugees out of ordinary citizens as it recalls the countless shoes discovered at concentration camps at the end of World War II.

For Salcedo, the ravine in the Tate Modern’s floor represents the immigrant experience in Europe, notably the racial segregation that marks immigrants of color as irrevocably “other,” a permanent state apart. Yet, the artist offers some hope. After seven months, the show ended and the Tate Modern filled the crack, leaving a scarred floor. This is a remarkable symbol of the possibility of healing through figurative and literal closure; however, the mark is also an obstacle to any attempts to erase the past.

Filled crack (detail), Doris Salcedo, Shibboleth, 2007–08, installation (Tate Modern, London; photo: Garrett Coakley, CC BY-SA 2.0) © Doris Salcedo

Sources

From an institutional perspective, this scar is remarkable for other reasons: it is usually unimaginable for museum officials to permit an artist to permanently alter the exhibition space.

Lucio Fontana, (Spatial Concept: Expectations), 1960, slashed canvas and gauze, 100.3 x 80.3 cm (MoMA, New York) © Fondation Lucio Fontana

Salcedo’s act remains transgressive: the act of deliberately breaking one’s media (in this case a concrete floor) is an act of rebellion. In this way, Shibboleth joins a tradition of artists experimenting with surface. In the late 1940s, Lucio Fontana developed “Spazialismo,” an approach to art-making that converted the two-dimensional canvas into a three-dimensional space. Fontana slashed his monochrome canvases, and revealed a new space underneath the gashes. The artist’s bold move to disrupt the canvas’s nearly sacred surface was revolutionary and influenced later artists.

Interior view (detail), Gordon Matta-Clark, Splitting, 1974 (Collection Centre Canadien d’Architecture) © Succession of Gordon Matta-Clark and Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark

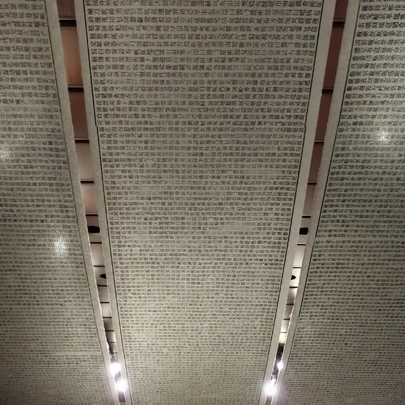

Throughout the 1970s Gordon Matta-Clark sawed into the walls, floors, and ceilings of buildings, often leaving cracks like the line of light in Splitting. For centuries, a canvas was a flat plane, the support for an image rather than an object in its own right. A building by definition sought to be structurally sound; any structural damage makes it unstable and dangerous. To highlight their subversion, these artists flaunt the negative space made by their incisions: Matta-Clark’s cuts in Splitting are illuminated by blinding light, while Fontana’s slashes and Shibboleth each reveal a startlingly dark void previously unseen.

Meanings

Matta-Clark, Fontana, and Salcedo create art that is difficult to classify. Is this painting? sculpture? architecture? installation? intervention? Salcedo’s strength as an artist is her ability to balance the formal impact of Shibboleth with its message, while preventing one from overshadowing the other. Salcedo’s reticence to discuss her process and meaning at length is our opportunity to develop infinite interpretations.

Doris Salcedo, Shibboleth, 2007–08, installation (Tate Modern, London; photo: Wonderferret, CC BY 2.0) © Doris Salcedo