Gordon Matta-Clark, Splitting, 1974 (Collection Centre Canadien d’Architecture, © Succession of Gordon Matta-Clark and Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark. Reprint made by the Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark from Matta-Clark negatives. Original photograph in the collection of SFMOMA)

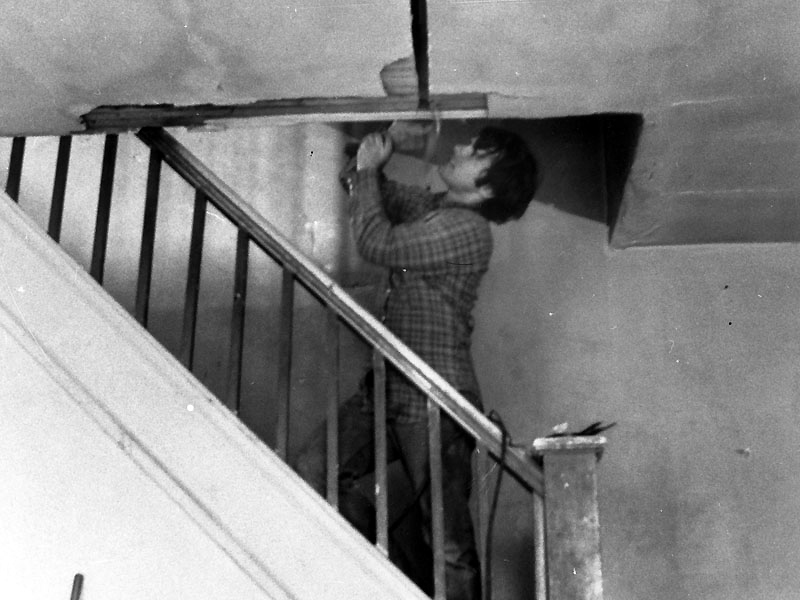

Gordon Matta-Clark in the process of cutting the roof in Splitting, 1974 (Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes)

Rather surprising things

“Over the past ten years,” the American art historian and critic Rosalind Krauss wrote in 1979, “rather surprising things have come to be called sculpture: narrow corridors with TV monitors at the ends; large photographs documenting country hikes; mirrors placed at strange angles in ordinary rooms; temporary lines cut into the floor of the desert.” [1] To this list, we could add Gordan Matta-Clark’s Splitting, 1974, in which a suburban home in Englewood, New Jersey slated for demolition was sliced nearly in half.

Matta-Clark had taken a chainsaw to make two parallel, vertical cuts beginning at the roof’s center; the house was nearly cleaved in half, each half shifted outwards leaving a long narrow “V” shape allowing light to filter inside. It was a laborious process that involved the assistance of several friends and the resulting structure, demolished some three months later as part of an urban renewal project, was documented in photographs.

Splitting also served as the site for at least one “field trip” — the art dealer Holly Solomon (who had purportedly purchased the house as an investment), several artists, and gallery goers boarded a bus from downtown Manhattan to visit the house (a 16 mm film, now in the collection of the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, documented the trip).

Still from Field trip to Gordon Matta-Clark’s “Splitting” house, c. 1974 (YouTube)

Post-medium

Beginning in the 1970s, contemporary art abandoned the traditional forms it had historically taken. Painting and sculpture became almost unrecognizable as such. Krauss would later characterize it as a “post-medium” condition, a condition, in other words, in which the familiar categories that defined Western art for centuries were overturned. The medium, that which constituted the material or form of a given artwork, became obsolete, or at least radically reformulated: an art work could now exist in any form.

If Gordan Matta-Clark could be said to be associated with any one particular medium, it would be architecture. The entirety of his work, of which Splitting stands as exemplary, consisted of alterations to the architecture of abandoned or condemned buildings. In his other work, sections of floors and walls were removed, and sometimes those removed sections themselves become the artwork; in other cases it was the void formed from the removal that is the focus.

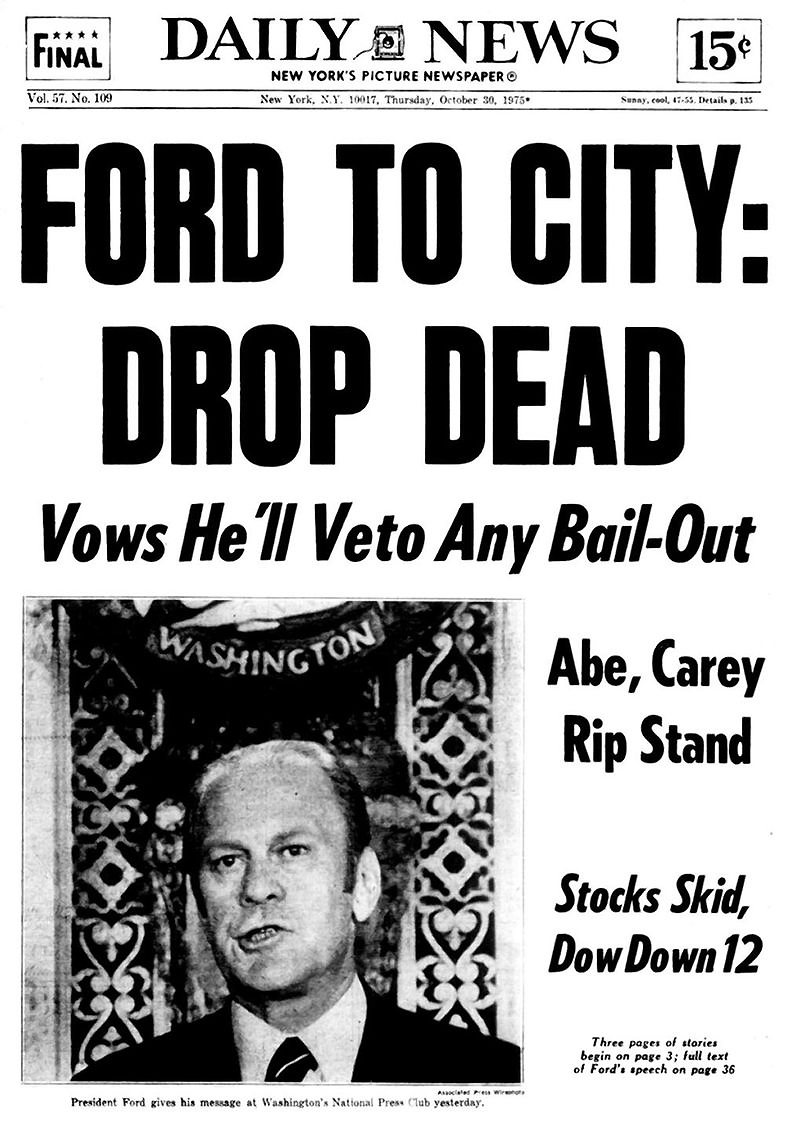

Matta-Clark began his interventions into the urban environment at a time when New York, where the artist lived and worked, was a city in crisis as a result of economic downturns. President Gerald Ford gave a speech denying federal assistance that would have rescued New York from what seemed like certain bankruptcy in the same year the artist made Splitting. The Daily News reported on its front page the very next day: “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD.”

The Daily News front page on Oct. 30, 1975 (New York Daily News)

Matta-Clark had seen his own neighborhood in lower Manhattan negatively impacted by modernization ever since the influential city planner Robert Moses attempted to push a freeway through Washington Square Park in the 1950s. Trained as an architect, Matta-Clark likely saw through the glossy rhetoric of urban renewal projects — though they promised regeneration such plans destroyed existing neighborhoods.

Anarchitecture

Gordon Matta-Clark at 112 Greene Street in 1972. Photographed by Charles Denson (Cosmos Andrew Sarchiapone papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

In March 1974, Matta-Clark joined a collective of artists who mounted an exhibition entitled Anarchitecture at 112 Greene Street in New York City. The premise was embodied in the title which merged the term “anarchy” with “architecture;” the artists in the collective were all interested in exploring new ideas of form and space in the midst of urban decay. One year later, and out of his experience working with this community of like-minded artists, came Splitting. But Matta-Clark’s destroyed house was not just giving visual shape to the crisis of a neighborhood or even of a city on the verge of collapse, dire as those conditions surely were.

Modernism formed the larger horizon of Splitting’s meaning; its philosophy of the new and of progress that had underwritten the utopianism of over 100 years of art and architecture was suddenly untenable. New York City had long defined industrial modernity — its soaring skyscrapers of the early twentieth century were second only to Chicago’s equally impressive skyline — and its seeming collapse was yet another symbol of a crisis of modernity. No wonder many people came to speak of postmodernity. In architecture particularly there was already a sense that the great utopian project of modernism had failed.

It has become almost obligatory to describe Matta-Clark’s work as a critique of modernist architecture — and more generally modernist art — an intervention, interrogation, disruption, investigation (all words you will encounter in the study of any postmodern or contemporary art work). But as much as Splitting may be regarded as critical commentary on the idea of progress and a work that helps to lay the groundwork for a postmodern aesthetic (in which artists were seen to be social commentators, engaged participants in the larger realm of visual culture, or even political activism), another aspect of the artist’s work bears consideration.

Gordon Matta-Clark, Splitting (interior view), 1974 (Collection Centre Canadien d’Architecture, © Succession of Gordon Matta-Clark and Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark. Reprint made by the Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark from Matta-Clark negatives. Original photograph in the collection of SFMOMA)

There is a melancholy and nostalgia that pervades Matta-Clark’s fragments of walls, floors, cut-through spaces or domestic interiors opened to the outside. Much like the fascination with the ruins of antiquity that peppered the landscape of Europe during the eighteenth century when classical antiquity was discovered anew, Matta-Clark’ s works speak in poignant tones of the demise of the modern as both an aesthetic ideal and a utopia.

Notes:

[1] Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,”October Vol. 8 (Spring, 1979), p. 30.

References:

Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,”October Vol. 8 (Spring, 1979), p. 30 – 44.

Rosalind Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition, London: Thames & Hudson, 2000.

Additional Resources:

The Canadian Centre for Architecture’s Gordon Matta-Clark Collection.