Élisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun, Archduchess Marie Antoinette, Queen of France, 1778, oil on canvas, 273 x 193.5 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

There is an oft-quoted saying misattributed to Marie-Antoinette, Queen of France, during a famine suffered by her subjects: If they have no bread, “then let them eat cake.”

In fact, this statement (which showed flagrant disregard for the suffering of the people) was never uttered by the Queen that we know from so many sumptuous portraits. These portraits are largely the work of Élisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun, a celebrated French artist known especially for her lavish portraits of Marie-Antoinette and other European monarchs and nobles as well as for her many self-portraits.

Detail, Élisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun, Archduchess Marie Antoinette, Queen of France, 1778, oil on canvas, 273 x 193.5 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Patron Queen

Vigée-LeBrun first met Queen Marie-Antoinette at the royal palace at Versailles in 1778. The Queen had heard of the young painter’s successes and had her own likeness painted en robe a paniers (in a hoopskirt). The painting is a majestic full-length display of power. Marie-Antoinette stands facing the viewer, with the exception of her head, which is turned slightly to the viewer’s left so that she looks past us.The Queen is dressed in an elaborate golden white dress. Her hair is piled high and she wears a feathery headdress. All around her are the accoutrements of her station: huge columns, a marble bust of her husband, Louis XVI, displayed high atop a pedestal and behind a table on which sits a crown. The painting was originally meant for the queen’s brother, Emperor Joseph II of Austria, but Marie-Antoinette was so pleased with it that she ordered copies made for Catherine the Great of Russia and her own apartments at Versailles.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun, painter

Élisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun, Self-Portrait, 1790, oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

The artist who created this opulent showpiece became famous and wealthy as Queen Marie-Antoinette’s official court painter. She was born to Louis Vigée and Jeanne Maissin in a bustling section of Paris. In her autobiography Souvenirs written towards the end of her life, Vigée-LeBrun wrote that her father, a minor portraitist, doted on her, wishing his daughter fame and good fortune; and that he cherished her early efforts at drawing. Vigée-LeBrun wrote that her mother thought her awkward and ugly. Nevertheless, she grew up to be intelligent, beautiful, rich, and talented, characteristics on display in her Self-Portrait of 1790.

Created soon after her swift departure from France at the onset of the French Revolution, Vigée-LeBrun’s Self-Portrait in the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence, is one of her best-known pictures. It is a late example of the Rococo style. Rococo epitomized a fashionable ideal, wherein perpetual youth was libertine and pleasure-loving, its sexual gratification taken without guilt or consequence. Despite this, the artist, like her royal patron, was extremely conservative in her politics.

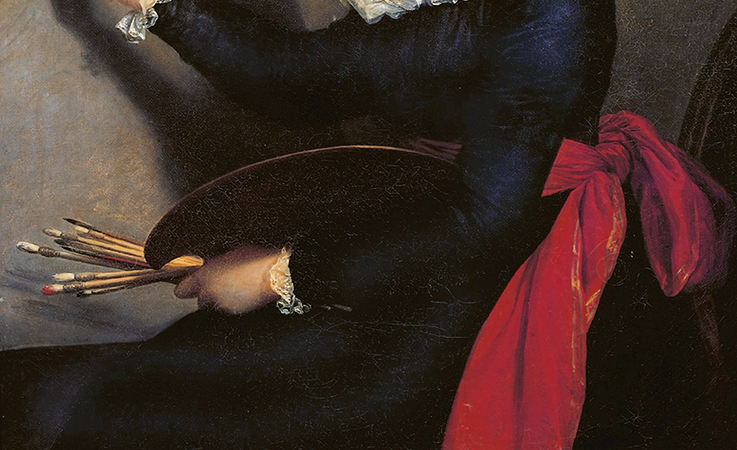

Detail, Elizabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait, 1790, oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi).

This self-portrait was painted in Rome; one of the first cities in which Vigée-LeBrun stayed during her decade-long exile from France. The artist sits in a relaxed pose at her easel and is positioned slightly off center. She wears a white turban and a dark dress—in the free-flowing style that Marie-Antoinette had made popular at the French court—with a soft, white, ruffled collar of the same material as her headdress. Her belt is a wide red ribbon. Vigée-LeBrun holds a brush to a partially finished work; the subject is probably Marie-Antoinette—perhaps intended as a tribute to her favorite sitter. Slightly used brushes are at the ready along with a palette, she has everything cradled in her arm close to the viewer.

The painting expresses an alert intelligence, vibrancy, and freedom from care. This, despite the fact that Vigée-LeBrun had been forced to flee France in disguise and under cover of darkness during the early stages of the Revolution. As she painted this portrait, her Queen was being driven from power by revolutionaries who hated the profligate lifestyle of the nobility and would later execute both Marie-Antoinette and her husband, King Louis XVI. Given these circumstances, Vigée-LeBrun—a working painter, wife, and mother—displays an extraordinarily sanguine persona.

Detail with palette and brushes, Élisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun, Self-Portrait, 1790, oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

Additional resources:

Gita May, Elisabeth Vigée-LeBrun: The Odyssey of an Artist in an Age of Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005).