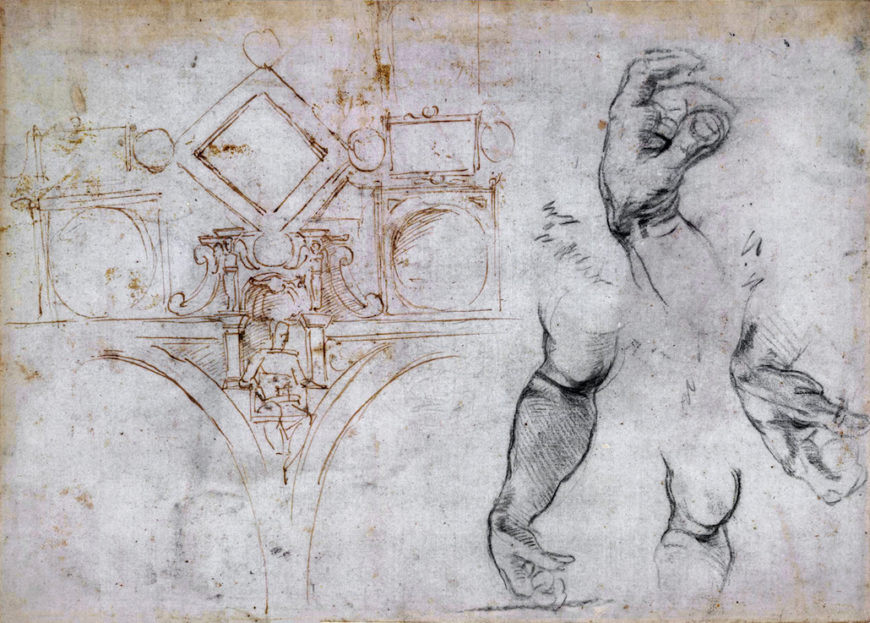

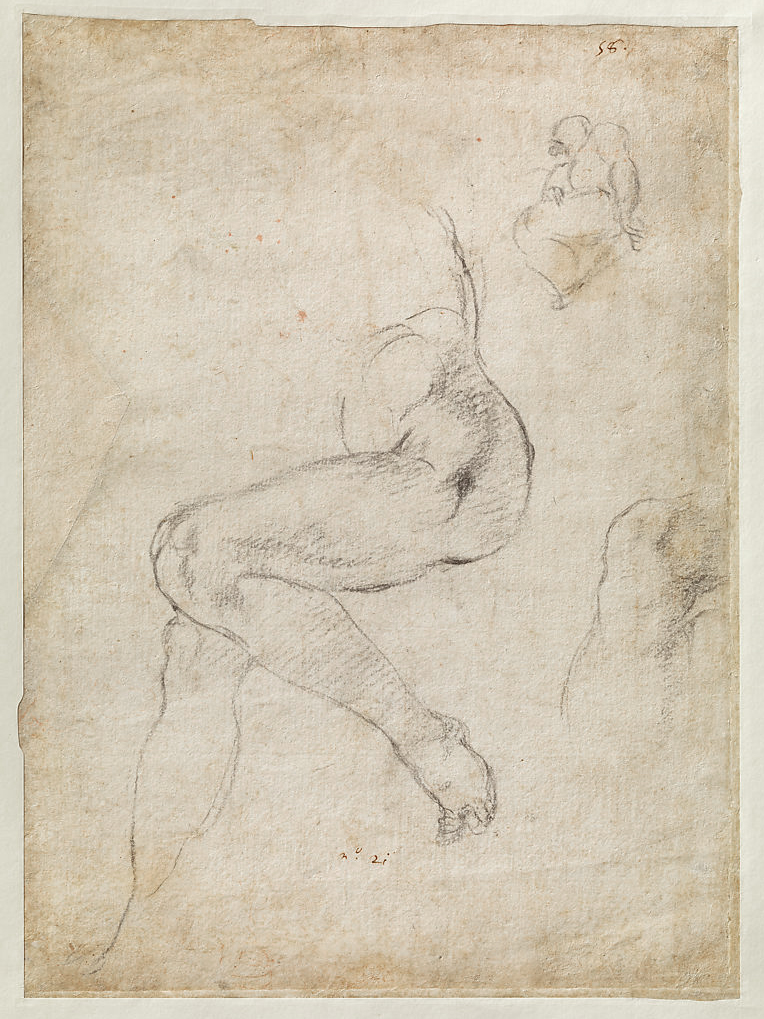

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Studies for the Libyan Sibyl (recto); Studies for the Libyan Sibyl and a small Sketch for a Seated Figure (verso), ca. 1510–11, chalk, 11 3/8 x 8 7/16″ / 28.9 x 21.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

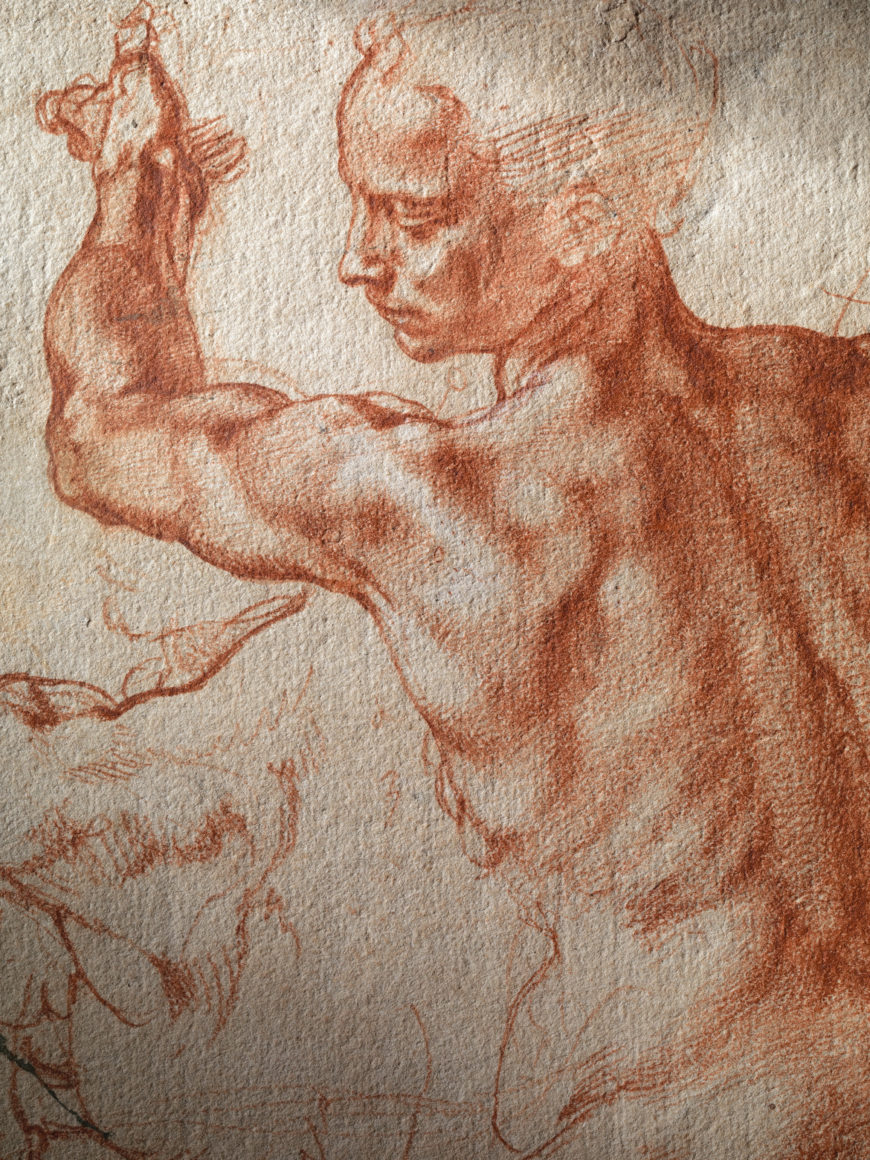

This is the most magnificent drawing by Michelangelo in the United States. A male studio assistant posed for the anatomical study, which was preparatory for the Libyan Sibyl, one of the female seers frescoed on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (Vatican Palace) in 1508–12. In the fresco, the figure is clothed except for her powerful shoulders and arms, and has an elaborately braided coiffure. Michelangelo used the present sheet to explore the elements that were crucial in the elegant resolution of the figure’s pose, especially the counterpoint twist of shoulders and hips and the manner of weight-bearing on her toe. Recent research shows that this sheet of studies was owned by the Buonarroti family soon after Michelangelo’s death. The “no. 21” inscribed on the verso of the sheet (at lower center) fits precisely into a numerical sequence found on many other drawings by the artist that have this early Buonarroti family provenance.

left: Michelangelo Buonarroti, Studies for the Libyan Sibyl (recto), c. 1510–11, red chalk, with small accents of white chalk on the left shoulder of the figure in the main study, 28.9 × 21.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); right: Michelangelo, Libyan Sibyl, c. 1511, fresco, part of the Sistine Chapel ceiling (Vatican Museums)

Michelangelo’s monumental Sistine Chapel ceiling frescoes are some of the most celebrated in all of art history. Among them is an image of the Libyan Sibyl, an ancient prophetess who looms large near the chapel’s main altar wall. A much smaller two-sided drawing, however, measuring slightly larger than a standard sheet of printer paper and living thousands of miles away tells a fascinating story of this oracle’s development. On one side, a red chalk drawing, known as Studies for the Libyan Sibyl, showcases Michelangelo’s impeccable abilities as a draftsman as he prepared for what would become part of the most expansive fresco commission of his career.

The Libyan Sibyl can be seen in the bottom left. Michelangelo, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, 1508–12, fresco (Vatican City, Rome)

The commission

Michelangelo, scheme for the decoration of the vault of the Sistine Chapel, studies of arms and hands, 1508, Pen and brown ink over a sketch in lead point and stylus, black chalk, 27.4 x 38.6 cm (©Trustees of the British Museum)

Michelangelo’s striking sibyl was created in preparation for one compartment of the multi-faceted decorative program commissioned by Pope Julius II in 1508 to adorn the chapel built at the behest of Pope Sixtus IV a century earlier (hence the name, Sistine Chapel). Though the chamber had already been filled with imagery along the walls, Pope Julius’ vision was one of renovation. His first focus was to update the ceiling—which was originally frescoed with stars set against a deep blue ground—to display the twelve apostles. Though the course of the ceiling’s design evolution is captured only through a handful of somewhat vague sketches—like one in the British Museum collection that showcases Michelangelo’s plans for some the ceiling’s framework—it seems clear that the original vision soon ballooned into an incredibly involved series of Old Testament scenes running along the central axis of the ceiling.

Michelangelo, Creation scenes, Sistine Chapel Ceiling, 1508–12, fresco (Vatican City, Rome) (photo: Dennis Jarvis)

Michelangelo only reached the Libyan Sibyl fresco near the culmination of the project, and she appears on the end of the ceiling adjacent to the chapel’s last Old Testament scene of God Dividing Light from Darkness.

In 1512, though, as Michelangelo put the finishing frescoed touches on his dramatic sibyl, the altar wall was notably different. It featured earlier artworks such as the Assumption of Mary by Pietro Perugino (surviving today only as a drawing in the Albertina collection) that would have reflected the more conservative figures of earlier Renaissance art. Thus, these this earlier altar wall’s design would have accentuated the visual contrast in styles that Michelangelo’s monumental ceiling figures presented.

Michelangelo, Monumentality, and Muscles

One of the most noted aspects of Michelangelo’s Sistine Ceiling is the evident growth in his fascination with the human figure and its monumentality as his designs progressed. This decisive shift is visible across the fresco cycle, as tightly clustered figures set within complex compositions seen in the earliest registers (by the chapel’s entrance) are eventually replaced with increasingly massive, muscular figures that project beyond their compositional enclosures.

This evolution can be seen across the sibyls themselves: Michelangelo’s Delphic Sibyl, executed closer to the beginning of the project, showcases a relatively modest figure neatly tucked into her niche. Meanwhile, the Libyan Sibyl served as the frescoed capstone of this progression by adhering to this new sense of monumentality. She seems to expand beyond her frame, her massive, muscular stature too significant to be contained within the bounds of the ceiling’s fictive architecture.

While these larger-than-life figures were likely more readable to those viewing them from below, such colossal figural compositions also gave Michelangelo license to explore his artistic passions for the body. As a result, just as the scale of these figures grew, so too did their musculature.

Detail of Studies for the Libyan Sibyl (recto), Michelangelo Buonarroti, Sistine Chapel ceiling, c. 1510–11, red chalk, with small accents of white chalk on the left shoulder of the figure in the main study, 28.9 × 21.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The drawing

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Small Sketch for a Seated Figure (verso), c. 1510–11, red chalk, with small accents of white chalk on the left shoulder of the figure in the main study, 28.9 × 21.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The drawing, in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, has two sides: a recto (front) and verso (back). On the back we see a truncated study of a lower body in a position similar to the Libyan Sibyl but that lacks detail—perhaps it was unfinished—and thus is difficult to decipher conclusively. On the front we see Studies for the Libyan Sibyl, where relatively more insights into Michelangelo’s process can be gained.

The recto (front)

The increasingly monumentality the Michelangelo employed is illustrated well in the drawing Studies for the Libyan Sibyl, most likely created between 1510–11 just as Michelangelo embraced this heroic proportion of the body. For example, the upper portion of the recto (front) drawing reveals Michelangelo’s impressive attention to the musculature of this sibyl’s upper back. Each rippling curve is conjured with an almost architectural detail as it projects from the figure using the artful play of highlight and shadow in red chalk. In the finished fresco, this sibyl is carefully draped with fabrics. Michelangelo’s drawing, though, reminds the viewer of his interest in constructing the body layer by layer—in other words, that the musculature beneath was equally as important as the draped fabric that eventually concealed it. He showcased this with the powerful torsion of the figure and reach of her arms, which combine with the sheer mass of muscles to convey a strikingly strong form.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, detail of Studies for the Libyan Sibyl (recto), c. 1510–11, red chalk, with small accents of white chalk on the left shoulder of the figure in the main study, 28.9 × 21.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Michelangelo Buonarroti, detail of Studies for the Libyan Sibyl (recto), c. 1510–11 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Beyond the study of musculature, this sheet also reveals Michelangelo’s dedication to draftsmanship. At center appears a delicate study of the sibyl’s left hand, articulating the parting of the fingers as she reaches to grasp the enormous book (of her prophecy) resting behind her. Similarly, along the right-hand edge of the drawing is a repeated study of the sibyl’s big toe as it bends to support the weight of the turning body. These elements speak to Michelangelo’s study of the body, but given they are relatively minute elements in an otherwise monumental fresco suggests that even when working on such a colossal scale Michelangelo lavished attention on even the tiniest of details. Furthermore, such detail as seen in this activated big toe gives the viewer a sense of the figure’s dynamism, as if she could spring forth with her prophetic text at any moment.

left: Michelangelo Buonarroti, Studies for the Libyan Sibyl (recto), c. 1510–11, red chalk, with small accents of white chalk on the left shoulder of the figure in the main study, 28.9 × 21.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); right: Michelangelo, Libyan Sibyl, c. 1511, fresco, part of the Sistine Chapel ceiling (Vatican Museums)

From Sibyl study to Sistine splendor

The fresco of the Libyan Sibyl took twenty giornate (days of work) to complete; we are left to guess, though, how long Michelangelo ruminated over the preparatory drawing. The detailed study of musculature along with the intricate reworkings through repeated study of parts of the body could have been done in rapid succession or through a long contemplation as Michelangelo considered one of his final—though no less daunting—additions to the Sistine Ceiling. What one can say, with confidence, is that Studies for the Libyan Sibyl offers a remarkable opportunity to consider the importance of a singular, small drawing to Michelangelo’s practice even when working on a colossal scale.