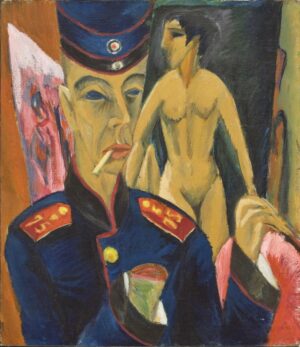

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Self-Portrait as a Soldier, 1915, oil on canvas, 69 x 61 cm (Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College)

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Self-Portrait as a Soldier is a masterpiece of psychological drama. The painting shows Kirchner dressed in a uniform, but instead of standing on a battlefield (or another military context), he is standing in his studio with an amputated, bloody arm and a nude model behind him. It is in this contrast between the artist’s clothing and studio space that we can read a complicated coming of age for an idealistic young artist.

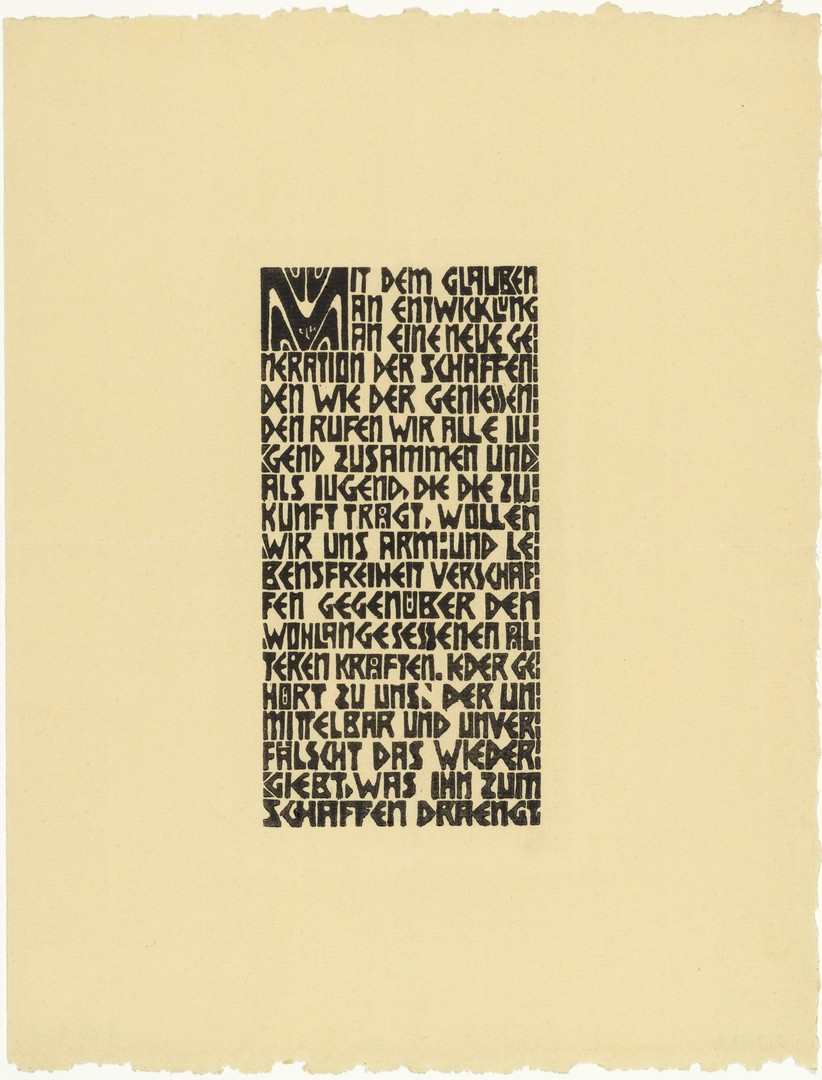

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Untitled, 1906, set of two woodcuts, 28.8 x 22.2 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Die Brücke

In 1905, Kirchner, together with several other young artists from Dresden founded the German Expressionist group Die Brücke (The Bridge). Kirchner created their manifesto, a woodblock print that was to be widely disseminated as a call to arms:

We call all young people together, and as young people, who carry the future in us, we want to wrest freedom for our actions and our lives from the older, comfortably established forces.[1]

Spurred on by their confidence and their belief that they lived in an age of great change, the Brücke artists set about creating an entirely new way of being artists. Kirchner was a great admirer of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche’s book Thus Spoke Zarathustra uses the bridge as a metaphor for the connection between the barbarism of the past and the modernity of the future. The Brücke artists considered themselves the inheritors of this idea, and created art that looked to the past and the future at once.

Another important influence on the Die Brücke artists was so-called “primitive” art (art and ritual objects from ancient cultures or non-Western societies, particularly in Africa and Central Asia). This art was perceived to be more honest and direct, more natural than work produced by artists from industrialized Western European nations. There was also interest in the so-called “folk art” of Europe, particularly the art and craft found among rural populations. It is important to note that Germany remained a major colonial power in Africa through the First World War. There is, therefore, a complex hierarchy that frames this cultural appropriation. While uncomfortable from the perspective of the 21st century, it is nevertheless undeniable that this “primitive” aesthetic (despite the fact that it is a modernist construction), had a strong impact on Expressionist art.

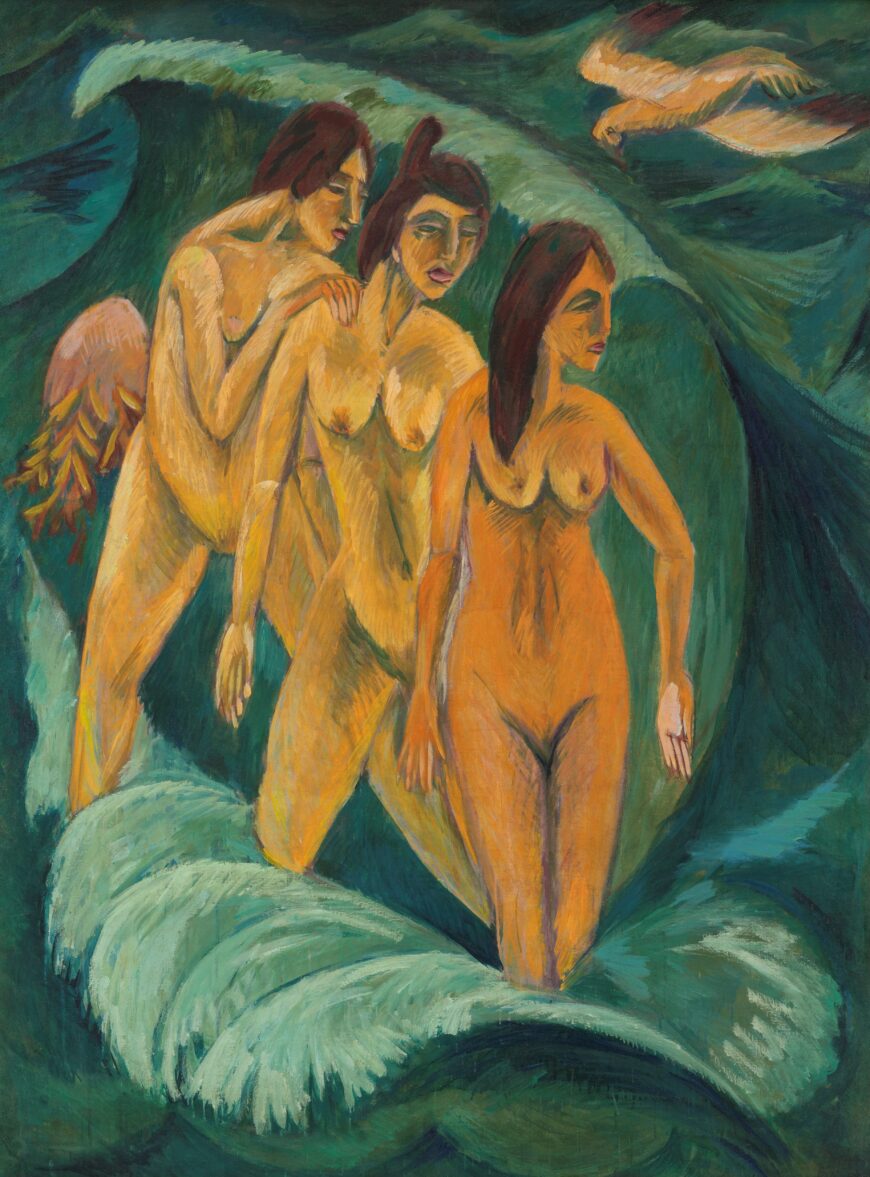

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Three Bathers, 1913, oil on canvas, 197.5 x 147.5 cm (Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney)

The Brücke artists were inspired to adopt the “natural” state that they perceived in “primitivism” in their lives and their art. Paintings created outside, in nature, together with the unidealized nudes were hallmarks of the group’s work. The roughly sketched, long forms and tapered limbs of the nude model in Self-Portrait as a Soldier is representative of the style of Kirchner’s nudes from this period and can be seen in his prints as well as paintings.

Although the Brücke disbanded in 1913, two years before Self-Portrait as a Soldier, each artist continued to develop individually and Kirchner’s Self-Portrait as a Soldier dates from one of his most highly-regarded periods of artistic production. Just a few years earlier he painted his iconic and dark Berlin street scenes (Potsdamer Platz and Street, Berlin), which employ a similar “primitive” style jarringly set into a modern metropolis. The young artist was coming into his own, but everything in Kirchner’s world was about to be interrupted by a cataclysmic event: the First World War.

Kirchner and the war

Kirchner volunteered to serve as a driver in the military in order to avoid being drafted into a more dangerous role. However, he was soon declared unfit for service due to issues with his general health, and was sent away to recover. Self-Portrait as a Soldier was painted during that recovery. These circumstances distinguish the 1915 canvas from other avant-garde projects of the period such as Otto Dix’s 1924 print series The War, in which the artist depicted the horrors he had witnessed first hand. Kirchner never fought, and this painting is instead an exploration of the artist’s personal fears.

The severed hand in Self-Portrait as a Soldier is not a literal injury, but a metaphor. This differentiates it in important ways from other depictions of wartime amputees, such as Dix’s many representations of wounded veterans designed to shame politicians with a grotesque view of the soldiers who were abandoned when they were no longer considered “useful” to the nation. Kirchner’s is a metaphoric, self-amputation—a potential injury, not to the body—but to his identity as an artist.

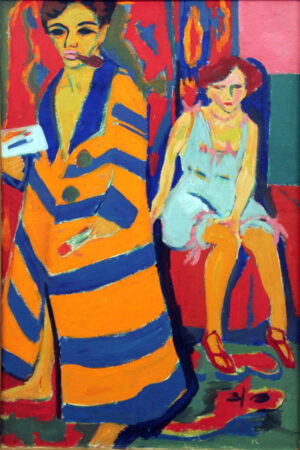

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Self-Portrait with Model, 1907/26, oil on canvas, 150.5 x 100 cm (Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg)

Self-Portrait as a Soldier can perhaps be best understood by comparing it with an earlier painting by the artist with similar subject-matter, his Self-Portrait with Model (1907/26). Here, a rounder, healthier-looking Kirchner stands confidently in his studio in a jaunty striped robe. He holds a brush and palette and seems to be wearing less clothing than the model seated behind him, clearly suggesting a sexual relationship. Even the warm colors give the work a sensuous atmosphere. This is the artist at the height of youthful confidence. Compare that with the sallow, angular artist we see in the Self-Portrait as a Soldier. The later painting features darker, colder colors, and the glassy-eyed model looks more like a carved statue than an actual person. Even the skinny, limp cigarette seems to stand in opposition to the robust pipe that the artist smokes in the earlier portrait. Kirchner the soldier stands impotently in his studio, surrounded with everything he would need to make art, were he able to do so.

The aftermath

During the war, Kirchner suffered from alcoholism and drug abuse and for a time his hands and feet were partially paralyzed. In a sense his fears about the war were self-fulfilling. Kirchner recovered and his work was exhibited internationally to much acclaim during the interwar period.

Adolf Hitler persecuted artists who painted in a style that he considered outside of the Aryan ideal soon after he became Chancellor of Germany in 1933. The Degenerate Art (Entartete Kunst) exhibition of 1937 was a grand spectacle that the Nazis organized to mock the modernist art they hated. This was a humiliating time for Kirchner. At least thirty-two of his works were exhibited in the Degenerate Art exhibition. In addition, more than 600 of his works were removed from public collections. He committed suicide in 1938.

Notes:

[1] Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Untitled (Die Brücke Manifesto) (1906).

Additional resources