Auguste Rodin, The Burghers of Calais, bronze, 1884–95 (Musée Rodin, Paris; this cast at Soldat Inconnu, Calais, France) (photo: Romainberth, CC BY 2.0)

Six men, one purpose

Have you ever been at a gathering surrounded by people and yet, felt completely and utterly alone? If you are familiar with those emotions—abandonment, loneliness, devastation—remember what it feels like and then take another look at the above sculpture by Auguste Rodin.

In 1885, Rodin was commissioned by the French city of Calais to create a sculpture that commemorated the heroism of Eustache de Saint-Pierre, a prominent citizen of Calais, during the dreadful Hundred Years’ War between England and France (begun in 1337).

We see six men covered only in simple layers of tattered sackcloth; their bodies appearing thin and malnourished with bones and joints clearly visible. Each man is a burgher, or city councilmen, of Calais, and each has their own stance and identifiable features. However, while they may stand together with a sense of familiarity, none of them are making eye contact with the men beside them. Some figures have their heads bowed or their faces obscured by raised hands, while others try to stand tall with their eyes gazing into the distance. They are drawn together not through physical or verbal contact, but by their slumped shoulders, bare feet, and an expression of utter anguish.

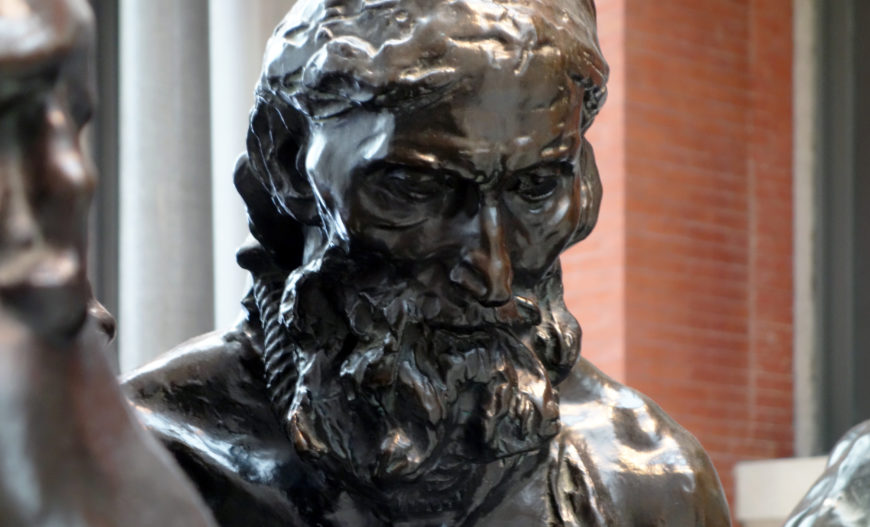

Detail of Eustache de Saint-Pierre, Auguste Rodin, The Burghers of Calais, bronze, 1884–95 (Musée Rodin, Paris) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Rodin followed the recounting of Jean Froissart, a fourteenth-century French chronicler, who wrote of the war. According to Froissart, King Edward III made a deal with the citizens of Calais: if they wished to save their lives and their beloved city, then not only must they surrender the keys to the city, but six prominent members of the city council must volunteer to give up their lives. The leader of the group was Eustache de Saint-Pierre, who Rodin depicted with a bowed head and bearded face towards the middle of the gathering. To Saint-Pierre’s left, with his mouth closed in a tight line and carrying a giant set of keys, is Jean d’Aire. The remaining men are identified as Andrieu d’Andres, Jean de Fiennes, and Pierre and Jacques de Wissant.

Detail of Jean d’Aire, Auguste Rodin, The Burghers of Calais, bronze, 1884–95 (Musée Rodin, Paris; this cast at the Hirshhorn Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.) (photo: Ron Cogswell, CC BY 2.0)

Unbeknownst to the six burghers, at the time of their departure, their lives would eventually be spared. However, here Rodin made the decision to capture these men not when they were finally released, but in the moment that they gathered to leave the city to go to their deaths. Instead of depicting the elation of victory, the threat of death is very real. Furthermore, Rodin stretched his composition into a circle causing no one man to be the focal point which allows the sculpture to be viewed in-the-round from multiple perspectives with no clear leader.

The commission

Auguste Rodin, Monument to Balzac, bronze, 1891-97 (Musée Rodin, Paris) (photo: smilla4, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Rodin spent most of his young life looking for approval and recognition. He was denied entry into the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris three times, and yet he continued to push forward until he could finally gain professional recognition. So, imagine his delight in 1885, when he was asked to create a monument for Calais. The only problem was he wanted to do it his own way.

It was common in the nineteenth-century to depict an event with a single heroic figure. For example, Rodin’s later sculpture Monument to Balzac (1891–97), where the French playwright and novelist, Honoré de Balzac, is shown standing tall and alone with his head held high. This is similar to what the city of Calais was inevitably expecting from Rodin. As a result, they were displeased with Rodin’s concept—they wanted only one statue; the one of Eustache de Saint-Pierre. Instead, Rodin included all six men from Froissart’s account.

A closer look

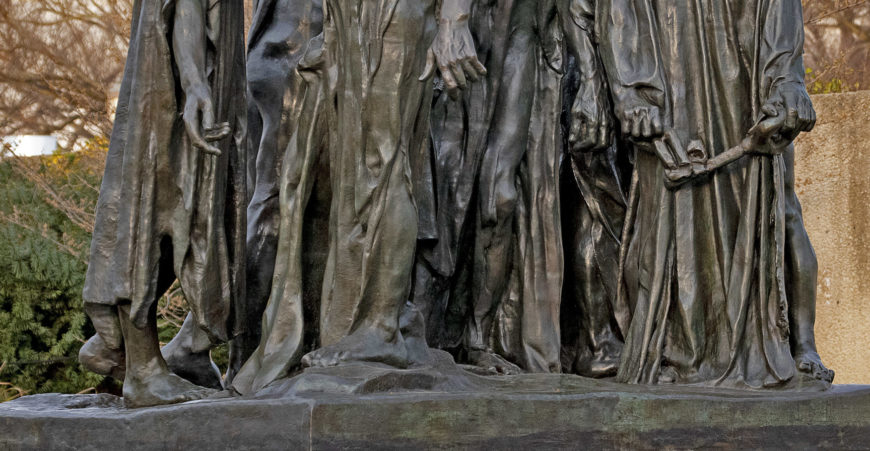

While these six men, at first glance, may look fragile, the heavy, rhythmic drapery that hangs from their shoulders falls to the ground like lead weights, anchoring them and creating a mass of strong, unyielding bodies.

Detail, Auguste Rodin, The Burghers of Calais, bronze, 1884–95 (Musée Rodin, Paris; this cast at the Hirshhorn Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.) (photo: Ron Cogswell, CC BY 2.0)

In fact, the fabric appears to almost fused to the ground—conveying the conflict between the men’s desire to live and the need to save their city. Rodin included raised portions of the floor under the men’s feet which would have, ultimately, made some of the men appear higher than others, yet they are all sculpted to be around the same height, that of an adult male. The burghers were not meant to be viewed in the form of a hierarchal pyramid with Eustache de Saint-Pierre at the top, which would have been typical in a multi-figure statue, but as a group equal in status. By bringing these men down to ‘street level,’ Rodin allowed the viewer to easily look up into the men’s faces mere inches from his/her own; enhancing the personal connection between the viewer and the six men.

The outcome

Detail, August Rodin, The Burghers of Calais, 1894–95, bronze (Musée Rodin, Paris) (photo: Greg Janée, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Because the patrons wanted a heroic quality, with a raised pedestal that would place the figures in a God-like status high above the viewers, Rodin presented the city of Calais with The Burghers of Calais complete with a pedestal. However, the raised pedestal did not allow an audience to view the work of art as Rodin had intended. Therefore, he created a second version, one lacking a pedestal, to be placed at the Musée Rodin at the Hôtel Biron in Paris. Rodin’s goal was to bring the audience into his sculpture of The Burghers of Calais, and he accomplished this by not only positioning each figure in a different stance with the men’s heads facing separate directions, but he lowered them down to street level so a viewer could easily walk around the sculpture and see each man and each facial expression and feel as if they were a part of the group, personally experiencing the tragic event.

Throughout his career, Rodin took risks and created his works of art in his own, albeit unconventional, way. As a result, Rodin set a standard for artists who came after him and his Burghers of Calais became one of his most well-known and studied works.

Additional resources

Breathing Life into Clay: Rodin and Modern Sculpture on ArtUK

Chronology of Rodin’s life from the Musée Rodin

The Burghers of Calais on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

Plaster cast at the Musée Rodin

First maquette at the Musée Rodin

More about this object from an educator resource by Nelly Silagy Benedek with The Met

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”RodinBurghers,”]