Eugène Delacroix, Women of Algiers, c. 1832–34, oil on canvas, 46 x 37.8 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Born in 1798, the French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix began life as child of privilege and grew up during the age of Napoleon. The funny thing is, he didn’t like being called a Romantic artist. Instead, Delacroix saw himself as a painter who carried on the tradition of French painting at its best, not as someone who wanted to overturn it. “Glory is not a vain word for me,” [1] he once wrote, and Delacroix imagined his name spoken in the same breath with the other “great” French painters such as Charles Lebrun and Jacques-Louis David. For nineteenth-century viewers, Delacroix seemed fearless in his ability to create dramatic images painted with an intensity of color and expression that no one else could match.

A young man in Paris

As a young man, Delacroix was at the heart of creative life in Paris and later became a hero of progressive artists and writers such as Baudelaire, Manet, and Monet, but he retained all of the elegance and ambition of his family’s aristocratic background. His father, Charles, found great success as a landowner and government official before his death in 1803. Delacroix’s brothers and other relatives served as soldiers and ambassadors in the Napoleonic government. Delacroix’s mother Victoire died in 1814, when Eugène was just sixteen. Although his father had left a fortune to his family, it had been poorly managed, and by 1822 there was nothing left. Delacroix would have to make his way in the world with just his talent and a few family connections.

Delacroix’s art owed much to his education and the company he kept as a young man in Paris. He attended the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, a prestigious school that is still associated with the French elite. There, and later in the company of his friends, he came to love Greek drama, Shakespeare, and modern literature. When he was seventeen, Delacroix entered the studio of the conservative painter Pierre-Narcisse Guérin and, as importantly, he began to study in the Louvre, copying the paintings of Veronese, Titian, and Rubens with other young painters.

Théodore Géricault, Raft of the Medusa, 1818–19, oil on canvas, 4.91 x 7.16m (Musée du Louvre, Paris, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In Guérin’s studio, Delacroix met the painter Théodore Géricault, who would have an important influence on Delacroix’s first major canvas (The Barque of Dante). Géricault’s dramatic brushwork and daring compositions made a deep impression on young Delacroix. In 1818, Géricault began to work independently on The Raft of the Medusa, in a studio rented specifically for that purpose. There Delacroix watched Géricault work quickly and expressively on the massive canvas. We know that Delacroix served as a model for one of the figures in the foreground, and he vividly recalled feeling completely overwhelmed with admiration and emotion when he saw the near-finished painting.

A dramatic debut

Delacroix’s first painting presented in the annual Paris Salon exhibition, The Barque of Dante (1822), reflected Géricault’s dramatic approach and all of Delacroix’s studies in the Louvre. Drawn from the Italian Renaissance poet Dante’s Divine Comedy, the painting depicts Dante guided into Hell by the Roman poet Virgil as stormy seas and demonic figures attack their boat. The figures and drama, recalling Michelangelo and Rubens, marked the artist as part of the new modern style that would soon be called Romantic.

The big three

After his debut painting, Delacroix followed up with three of his best-known works, all drawn from contemporary events and literature. These paintings marked Delacroix as the leader of the modern, Romantic movement. In the public imagination, the term Romantic pitted Delacroix against the more conservative painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who embodied a conservative, classic approach to painting based on the primacy of line, while Delacroix represented a more expressive, modern painterly style focused on color. While Delacroix never liked being labeled a Romantic, he valued all the recognition that came from presenting sensational Salon paintings.

Eugène Delacroix, Massacre at Chios, 1824, oil on canvas, 419 × 354 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Massacre at Chios depicts the Greeks of the island of Chios after a defeat by the Ottoman Turks during the Greek Wars of Independence. The French saw themselves reflected in the Greek struggle for freedom, and the Turkish cavalryman on the right added drama and foreign glamour. There was always a crowd in front of the painting at the Salon exhibition. Delacroix offered the viewers a bit of tradition and, also, painterly innovation. The frieze-like composition of figures across the canvas recalled the Neoclassical paintings of Jacques-Louis David, and conservative critics liked the reclining, bearded male figure. Those with a taste for a more progressive, Romantic style responded to the fluidity of the painting and intense color contrasts that seemed drawn from Rubens and expressed the passionate nature of the artist.

Eugène Delacroix, The Death of Sardanapalus, 1827, oil on canvas, 12 ft 10 in x 16 ft 3 in. (3.92 x 4.96m) (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Next came the epic Death of Sardanapalus (1827), a massive canvas depicting the last Assyrian king watching his concubines and horses being slaughtered as he burns his palace down around him. The subject is taken from a play by the Romantic English poet Byron, and the painting is a swirling, violent scene dominated by a red that permeates the canvas. Audiences were shocked and dazzled. The painting reflected contemporaneous French ideas of the people of the East as hedonistic, violent and fatalistic. This worldview, associated with the term Orientalism in art history, was part of an overall colonialist attitude that defined Western Europe as a model of reason and moderation in contrast to the excesses associated with the so-called Orient. As such, the audience could revel in the violence, eroticism and glamour because it depicted a world defined as completely different and removed from modern Paris. But, for most viewers, Delacroix had gone too far. The painting broke too many rules. Even his supporters discerned no underlying structure to the painting’s composition and saw only an indulgent use of color.

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People (July 28, 1830), September–December 1830, oil on canvas, 260 x 325 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0))

One of the most famous paintings in France completes the trio: Liberty Leading the People (1830). It commemorates the Revolution of 1830 that deposed Charles X (brother of Louis XVI) and brought an end to the Bourbon Restoration that had followed Napoleon. The events of 1830, unlike the conflict in Greece or the violent fantasy of Sardanapalus, unfolded on Delacroix’s doorstep. Rather than taking part in the conflict, he stayed off the streets and out of danger. Only after order was restored did he take a stand. He wrote, “I have undertaken a modern subject, a barricade, and although I may not have fought for my country, at least I shall have painted for her.”[2] While many saw a call to revolution in Liberty Leading the People, Delacroix saw a classic history painting with an allegorical figure, bare-breasted Liberty, carrying the tricolor flag of the French republic over the barricade.

For the official world of French painting, Liberty Leading the People posed a problem. In a country so rocked by revolutions and violence in the previous decades, was it prudent to have a painting celebrating rebellion on public view? This question dogged the French state for decades. After its first exhibition in the Paris Salon, Delacroix was awarded the cross of the Legion of Honor, and the painting was purchased by the state and put on view in Paris’ gallery of contemporary art in the Luxembourg Palace. But by 1832 the monarchy removed the painting, and it was not exhibited again until 1848. It was removed again in 1850 and not put on permanent display until 1862. Today, it is an iconic image of the ideals of the French republic.

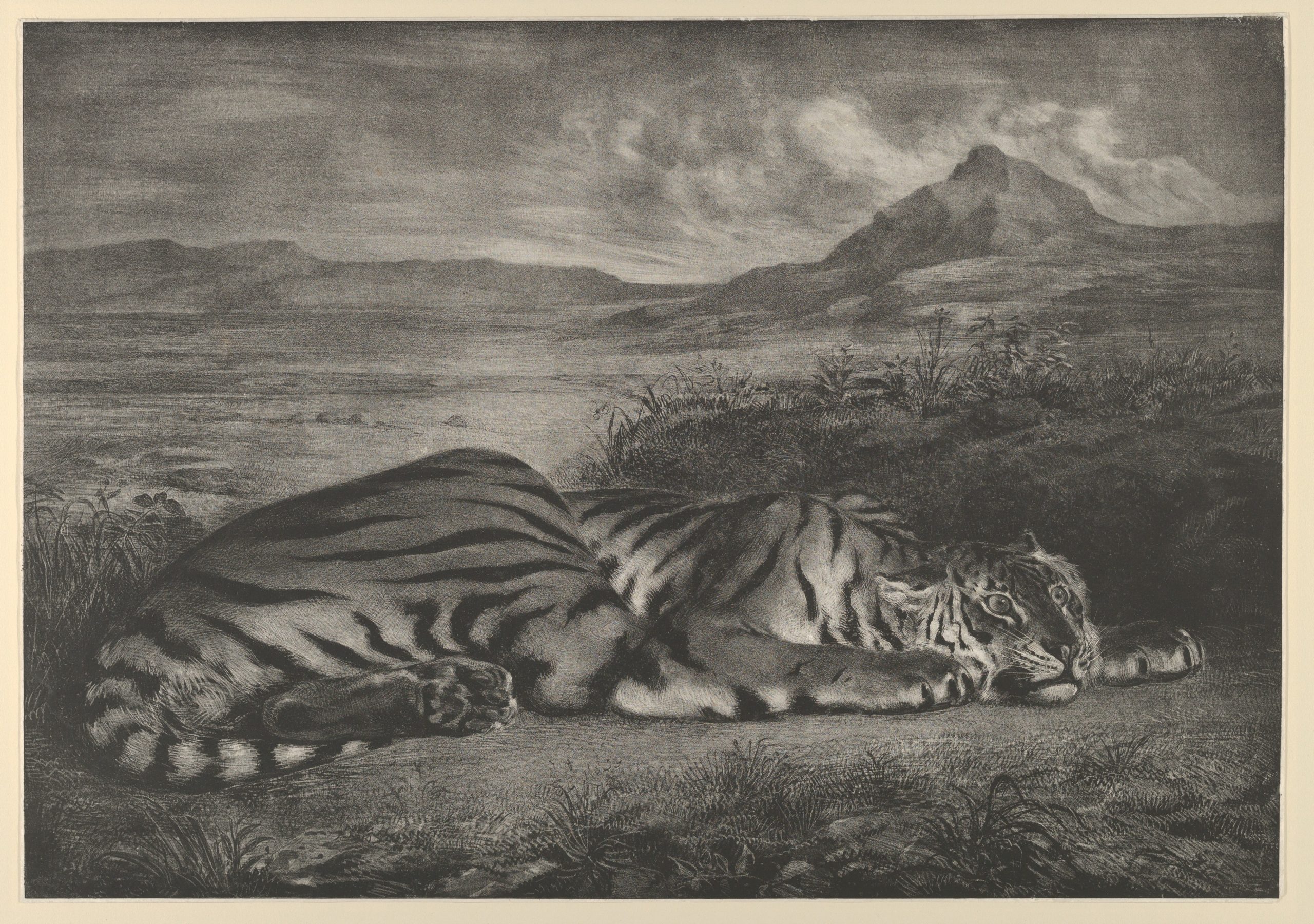

In the years after Liberty Leading the People, Delacroix shifted his focus from large-scale canvases for the Salon to new subjects. Through his association with members of the government, he was invited to North Africa as part of a diplomatic mission and produced work from that voyage. Later he received commissions to create wall and ceiling paintings for important government buildings and churches in Paris. This was not his only work, but these projects shaped his professional life. During these years, his friends were well-known bohemian artists, writers and composers, such as the novelist George Sand and her lover, the composer Frédéric Chopin. With the Romantic sculptor Antoine Barye, he visited the Paris zoo to draw and paint the exotic tigers and other animals. He also worked as a printmaker, producing etchings and lithographs that included images of animals, depictions of North Africa and illustrations from literature.

A voyage to Morocco

In January 1832, Delacroix, who had not traveled outside of France before, took part in a diplomatic mission to Morocco. Before the trip, he had only known the world of North Africa and the Middle East from literature and images. After his arrival in Tangier, he wrote a friend, “I have just walked through the city. I am dizzy with what I have seen.”[3] One of the earliest French painters to depict the people and cultures of North Africa, Delacroix filled his notebooks with ink sketches and watercolors.

Eugène Delacroix, Women of Algiers, c. 1832–34, oil on canvas, 46 x 37.8 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

When he returned to Paris, Delacroix began to exhibit work drawn from his voyage, beginning with A Street in Meknes (1832). Most significant was The Women of Algiers (1834) exhibited to great acclaim in the Paris Salon. According to contemporary writer Philippe Burty, Delacroix had received special permission to enter an Algerian harem — part of a home off-limits to men — and sketched two women he encountered there. He used the visit and his sketches as the basis for the two principal figures in The Women of Algiers. While this account is in doubt today (after all, he created the painting in Paris using models in the studio), the Salon audience was entranced, embracing the quiet intimacy of the scene, its exotic aura, and beautiful intense colors. Delacroix returned to the subject fifteen years later with The Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1847-1849) and other artists, such as Pablo Picasso, closely studied and rendered their own versions of the painting.

Eugène Delacroix, The Women of Algiers in Their Apartment, 1847–1849, oil on canvas, 85 × 112 cm (Musée Fabre, Montpelier, France)

Paintings for all of Paris

Delacroix also found success creating decorations for important public buildings and churches in Paris. In 1833, he began work on government commissions with paintings for important rooms in the Assemblée Nationale, and followed up with decorations for the library of the Senate (1840–1851). Between 1851 and 1854, he also painted the Salon de la Paix in the Paris City Hall, although his work was unfortunately lost in the fire of 1871. Visitors to the Louvre can see some of Delacroix’s decorative paintings in the Galerie d’Apollon, including Apollo Slays Python, from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Before beginning the painting, Delacroix had visited Belgium and his journals record admiration for the freedom, drama, and sublime nature of Rubens’ work that found its way into the swirling colors, dramatic composition, and ethereal light of Apollo Slays Python.

Eugène Delacroix, Apollo Slays Python, 1848–1851, oil on canvas, 85 × 112 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris, photo: Slices of Light, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The monumental paintings created after 1830, during the July Monarchy, were followed by a commission to decorate the Chapelle des Anges in the Church of St. Sulpice. He received the commission in 1849, but other work delayed the start on the paintings until 1854. In the Chapelle he depicted three stories that revolved around the biblical Archangel Michael and stories from the Old Testament. This would be his last major project.

Eugène Delacroix, Heliodorus Vanquished from the Temple, part of a mural cycle in the Chapel of the Holy Angels, completed 1861, Church of Saint-Sulpice, Paris (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The end of an era

As he completed major Salon paintings and public commissions, Delacroix also continued to create smaller easel paintings. Throughout his career he drew, printed, and painted dramatic subjects drawn from history and literature, tales from mythology and Christian subjects that reflected compassion and empathy, as well as animal and still-life images. At his funeral in 1863, people said that his death marked the end of an era in French art and the definitive passing of the “Generation of 1830.” Yet even as Delacroix passed into history, a new generation of rebellious painters led by Édouard Manet had begun to follow in his footsteps by creating art that engaged with the past while pushing toward an entirely new approach to painting.

Notes:

- Eugène Delacroix, Journal, April 29, 1824.

- Barthélémy Jobert, Delacroix (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1997), 130.

- Ibid., 83.

Additional resources:

Eugène Delacroix at the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Explore the Galerie d’Apollon at the Louvre

Works by Pierre-Narcisse Guérin at the Harvard Art Museums