Sandro Botticelli, Portrait of a Man with a Medal of Cosimo il Vecchio de’ Medici, c. 1474, tempera on panel, 57.5 x 44 cm (Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence)

When browsing a museum, I’m sure we’ve all experienced the strong desire to touch a work of art (we know we shouldn’t, but I think we can admit we’ve all wanted to). Well, Sandro Botticelli’s Portrait of a Man with a Medal of Cosimo il Vecchio de’ Medici was made to incite touch, or at least to make viewers think about touch and physical experience.

Seeing Botticelli’s Portrait of a Man reproduced online, in the pages of a book, or even when walking past it in Florence’s Galleria degli Uffizi, where it is protected by a layer of glass, modern viewers may miss a key aspect of the painting. However, the typical fifteenth-century viewer of this portrait likely would have been able to touch the object itself, and at the very least could easily draw from memory the experience of handling an object much like the medallion held by the portrait sitter, as portrait medallions were frequently dispersed and collected among the upper classes.

Sandro Botticelli, detail of Portrait of a Man with a Medal of Cosimo il Vecchio de’ Medici, c. 1474, tempera on panel, 57.5 x 44 cm (Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence; photo: dvdbramhall, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Upon closer inspection, you’ll notice that this isn’t a two-dimensional portrait painting, but a multimedia work. The sitter is indeed painted quite naturalistically, so he looks three-dimensional, as though he could potentially exist in our world. The medallion that he holds, however, actually is three-dimensional. This portrait, like many paintings in fifteenth-century Italy, is painted with tempera on a wood panel. In this case, a hole has been cut in the panel, where the sitter appears to be holding the medallion, and a copy of a real portrait medallion has been inserted into that space.

This pseudo-medallion is not actually made of metal, as a true medallion is, but it is instead built of pastiglia, a paste or plaster, made with gesso and built in low relief. In this portrait, the pastiglia medallion has also been gilded, or covered in a thin layer of gold leaf, to mimic the appearance of a gilded bronze medallion. Because the image and text on this pseudo-medallion exactly mimic the orientation of Cosimo’s portrait on real medallions from this period, it is possible that Botticelli used the impression of an existing medallion to make a mold, or had access to a mold used to create such medallions.

Cosimo de’ Medici, c. 1480–1500, bronze medal, made in Florence (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Who is this man?

Well, we don’t know, despite much scholarly speculation over the years. We can discern that he is certainly intending to associate himself with one of the most powerful families in Italy at this time, the Medici. He does so by holding a large copy of a real, existing portrait medallion—an object that would have been made in multiples, circulated, traded, and collected by humanists and upper-class members of Renaissance society.

The young man in Botticelli’s portrait looks directly out at the viewer and appears proud of his connection to the object that he holds. He displays the large medallion right over his heart, an organ that was associated with the creation of lasting memories and the storage of sense impressions. The sitter is dressed as a humanist, a learned member of Florentine society.

Left: Cosimo de’ Medici, c. 1480–1500, bronze medal, made in Florence (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London); right: Trajan Denarius, Roman Dacia, 107 C.E. (Roman Numismatics Collection; photo: courtesy of James Grout/Encyclopedia Romana)

The medallion, as a copy of a real object, shows the profile view of Cosimo il Vecchio (the Elder), with Latin text arching above his portrait. The text makes reference to Cosimo il Vecchio as pater patriae, or “Father of the Fatherland.” This phrase indicated the political power of the Medici, which began during Cosimo’s lifetime. The format of the pseudo-medallion is drawn from coins and medals of Greek and Roman antiquity, thereby effectively associating Cosimo with great rulers of a learned past, a past that Renaissance humanists hoped to emulate.

Who were the Medici?

Why would someone in Renaissance Italy want to be associated with the Medici family? And why Cosimo il Vecchio, in particular? The Medici were the most powerful family in Florence, and remained one of the most influential families in Italy—and Western Europe more broadly—throughout the Renaissance. Even though Cosimo il Vecchio was deceased by the time of this portrait, he was remembered as the de-facto “father” of the wealthy banking, mercantile, and political family. Beginning with Cosimo and his political rule, the Medici helped to make Florence the cradle and birthplace of the Italian Renaissance, as they were responsible for financially supporting many advances in the arts and humanities. By 1475, when this portrait was painted, the grandsons of Cosimo, Lorenzo and Giuliano, were co-rulers of Florence. Just a few years later, in 1478, Giuliano was killed in the Florentine Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore (the Duomo) during the assassination plot known as the Pazzi Conspiracy. At this time, Lorenzo il Magnifico (the Magnificent) de’ Medici became head of the family and the Medici rule in Florence.

Lorenzo, in particular, surrounded himself and filled his court with artists, architects, writers, and other humanist scholars. Sandro Botticelli was one of these, looked upon quite favorably by Lorenzo and given numerous commissions during his time as a court painter for the Medici. This portrait was thus created during one of the great heights of Medici Renaissance power and influence. In just a few decades, in fact, two members of the family would become popes—Pope Leo X (Giovanni di Lorenzo de’ Medici) and Pope Clement VII (Giulio di Giuliano de’ Medici). In short, if one had the ability to claim even a tangential connection to the Medici family, it would only make sense to document that connection for eternity in a work of art, such as our Man with a Medal.

Sandro Botticelli, Adoration of the Magi, c. 1475–76, tempera on panel, 111 x 134 cm (Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence). A self-portrait of Botticelli appears on the far-right side; he is the man looking out at viewers and dressed in golden robes.

Botticelli, the Medici, and Renaissance portraiture

And, again, Botticelli was able to claim just such a connection himself. In fact, the artist famously includes his self-portrait in an image of the Adoration of the Magi, also painted around 1475. The Medici were known to frequently associate themselves with the three kings as a way of showing their loyalty to the Christian faith and their will to also gift expensive things to Christ (carried out in the Renaissance by way of commissioning religious works of art and architecture). As such, many recognizable portraits of Medici family members can be found in the Adoration of the Magi. Botticelli perpetually commemorates his connection to this powerful family by adding his own portrait to the group.

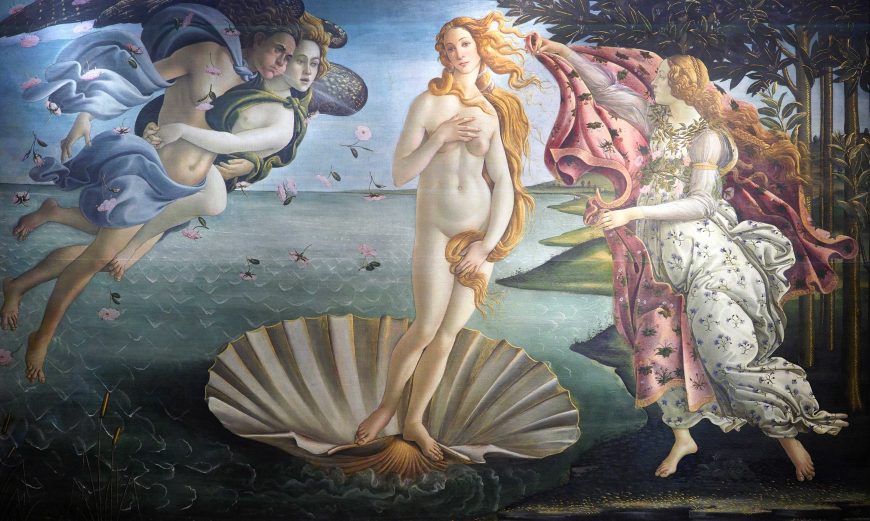

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, 1483-85, tempera on panel, 68 x 109 5/8″ (172.5 x 278.5 cm) (Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The best-known works by Botticelli are religious and mythological scenes, such as his Birth of Venus, which can also be found in the Uffizi Gallery. However, Botticelli was also widely celebrated for his technical abilities in the genre of portraiture. In the last quarter of the fifteenth century, artists were continually working towards creating ever more communicative and naturalistic portraits.

Two examples of northern renaissance portraits. Left: Jan Van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, tempera and oil on oak panel, 82.2 x 60 cm (National Gallery, London; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Petrus Christus, Portrait of a Carthusian, 1446 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Moving away from the classically-inspired strict profile format and turning to a three-quarter twist of the body inspired by Flemish portraiture, artists like Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, and Antonello da Messina were revolutionizing the entire genre of portraiture.

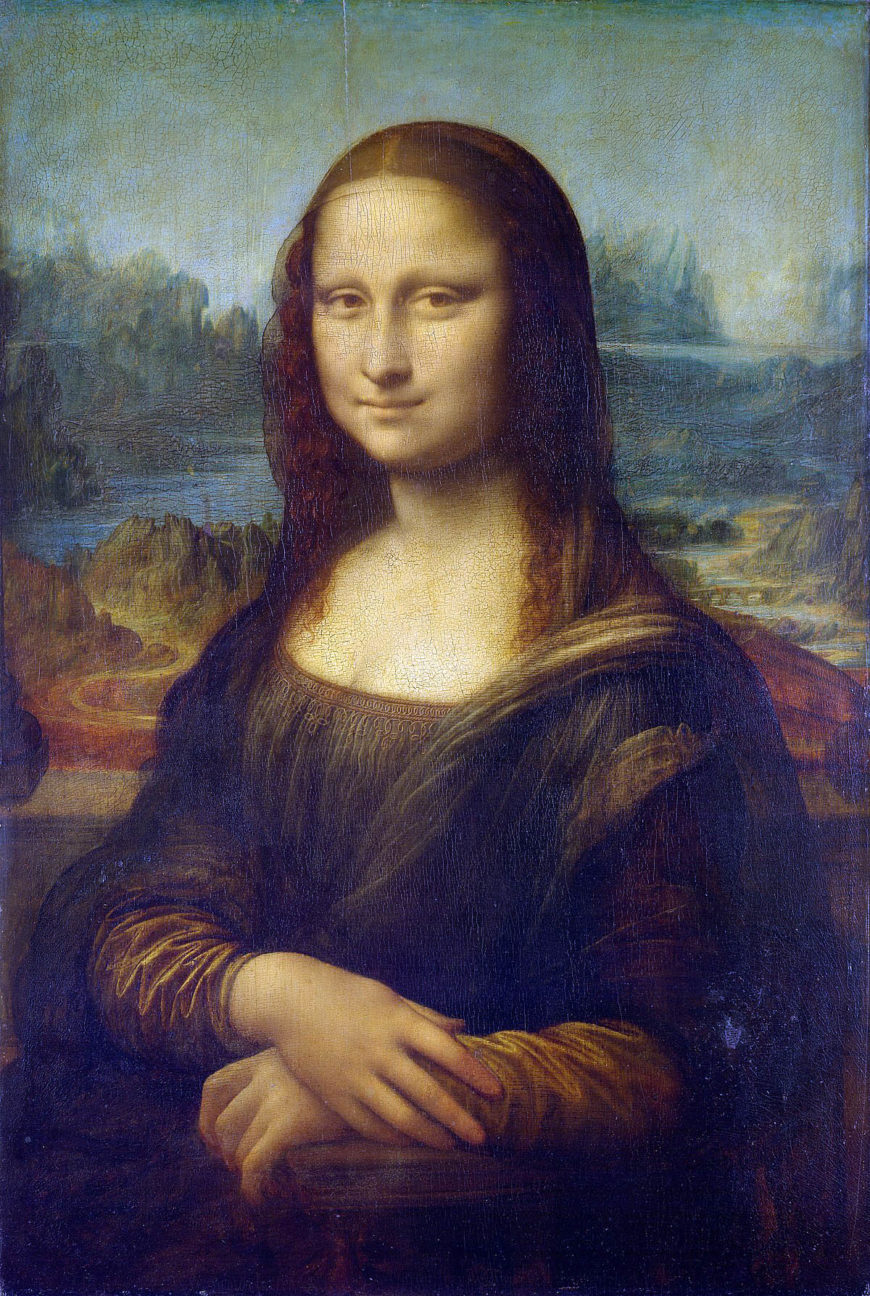

Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of Lisa Gherardini (Mona Lisa), c. 1503–05, oil on panel, 30-1/4″ x 21″ (Musée du Louvre)

Painters from regions north of the Alps created portrait likenesses that turned toward their viewers and appeared to make eye contact, ultimately inspiring Italian artists, already heavily invested in naturalism, to do the same. In addition, Leonardo da Vinci’s portraits, as well as many of Botticelli’s, also began to incorporate more of the body (consider, for example, how a viewer sees the entire turn of the Mona Lisa‘s upper body, even the placement of her hands), thereby adding an even greater sense of physical presence to the sitters.

Sandro Botticelli, Portrait of a Man with a Medal of Cosimo il Vecchio de’ Medici, c. 1474, tempera on panel, 57.5 x 44 cm (Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence)

A truly unique portrait

Botticelli’s Portrait of a Man with a Medal of Cosimo il Vecchio de’ Medici is particularly special because it incorporates the “old” format of portraits in its medallion—those in strict profile, meant to reference similar objects from antiquity—along with the newly popularized approach that captured more lively and communicative sitters, sitters that make eye contact with their viewers. Here, Botticelli’s young man looks directly out at us, capturing our attention and thereby directing it to what he holds. We feel as though he is speaking to us, asking us to touch this three-dimensional medallion and to remember his status, amplified by his ties to this important family. The artwork combines old and new, painting and sculpture, to create one of the most unique and enthralling portraits of its time.

Additional Resources:

This portrait on the Gallerie degli Uffizi website

Read more about the presentation of self in the Italian renaissance via Italian renaissance learning resources

Why commission artwork during the renaissance?

Types of renaissance patronage

View another Italian renaissance artwork that uses pastiglia on Smarthistory

Read more about the Medici as collectors

Francis Ames-Lewis, ed., The Early Medici and Their Artists (London: Birbeck College, 1995).

Allison M. Brown, “The Humanist Portrait of Cosimo de Medici, Pater Patriae,” Journal of the Warburg and the Courtauld Institutes, vol. 24, no. 3/4 (1961), pp. 186–221.

Rebecca M. Howard, “A Mnemonic Reading of Botticelli’s Portrait of a Man with a Medal,” Source: Notes in the History of Art, vol. 38, no. 4 (2019), pp. 196–205.

Richard Stapleford, “Botticelli’s Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Trecento Medallion,” Burlington Magazine, vol. 129, no. 1012 (1987), pp. 428–436.