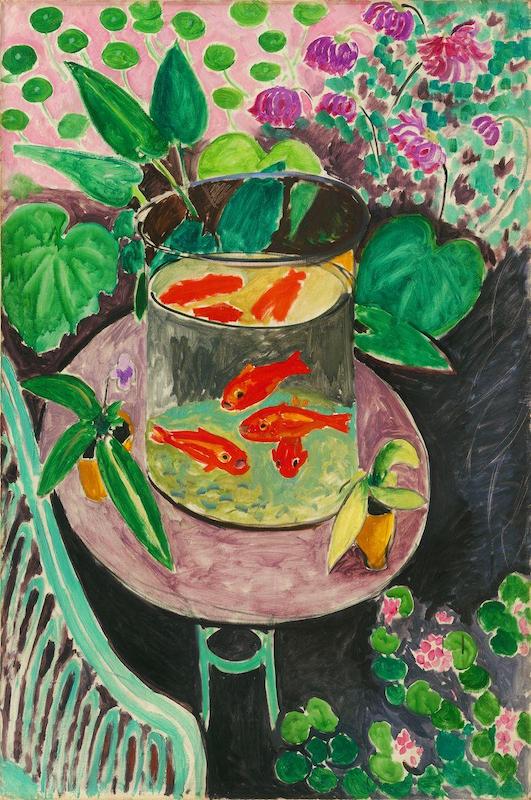

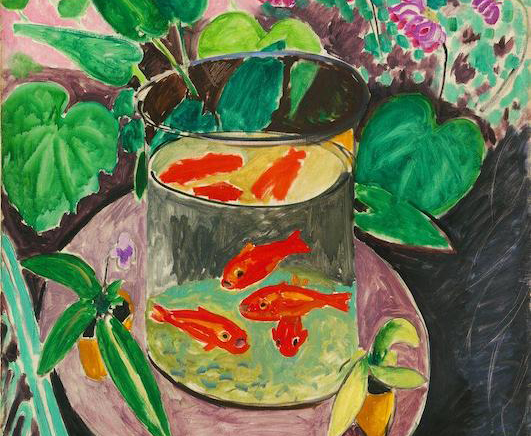

Henri Matisse, Goldfish, 1912, oil on canvas, 146 x 97 cm (Pushkin Museum of Art, Moscow)

Goldfish were introduced to Europe from East Asia in the 17th century. From around 1912, goldfish became a recurring subject in the work of Henri Matisse. They appear in no less than nine of his paintings, as well as in his drawings and prints. Goldfish, 1912 belongs to a series that Matisse produced between spring and early summer 1912. However, unlike the others, the focus here centers on the fish themselves.

Color

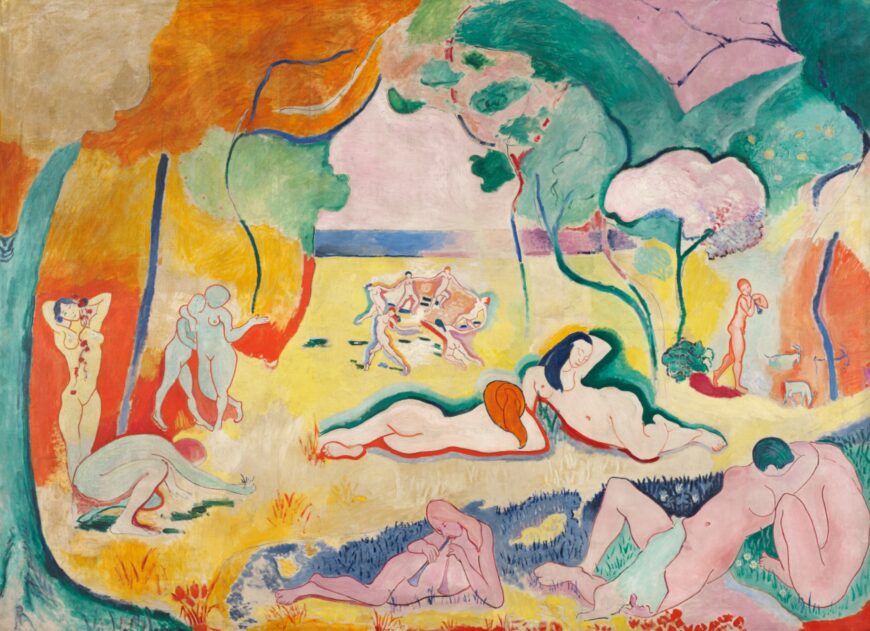

The goldfish immediately attract our attention due to their color. The bright orange strongly contrasts with the more subtle pinks and greens that surround the fish bowl and the blue-green background. Blue and orange, as well as green and red, are complementary colors and, when placed next to one another, appear even brighter. This technique was used extensively by the Fauves, and is particularly striking in Matisse’s earlier canvas Le Bonheur de vivre. Although he subsequently softened his palette, the bold orange is reminiscent of Matisse’s fauvist years, which continued to influence his use of color throughout his career.

Henri Matisse, Bonheur de Vivre, 1906, oil on canvas, 175 x 241 cm (Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia)

Golden age

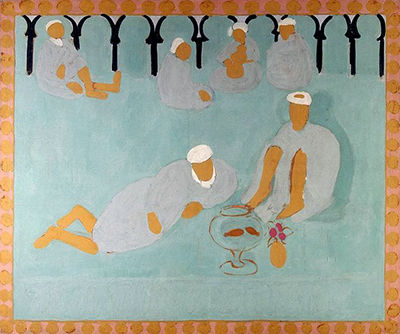

Henri Matisse, Le café Maure (Arab Coffeehouse), 1911–13, oil on canvas, 176 x 210 cm (Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg)

But why was Henri Matisse so interested in goldfish? One clue may be found in his visit to Tangier, Morocco, where he stayed from the end of January until April 1912. He noted how the local population would day-dream for hours, gazing into goldfish bowls. Matisse would subsequently depict this in The Arab Café, a painting he completed during his second trip to Morocco, a few months later.

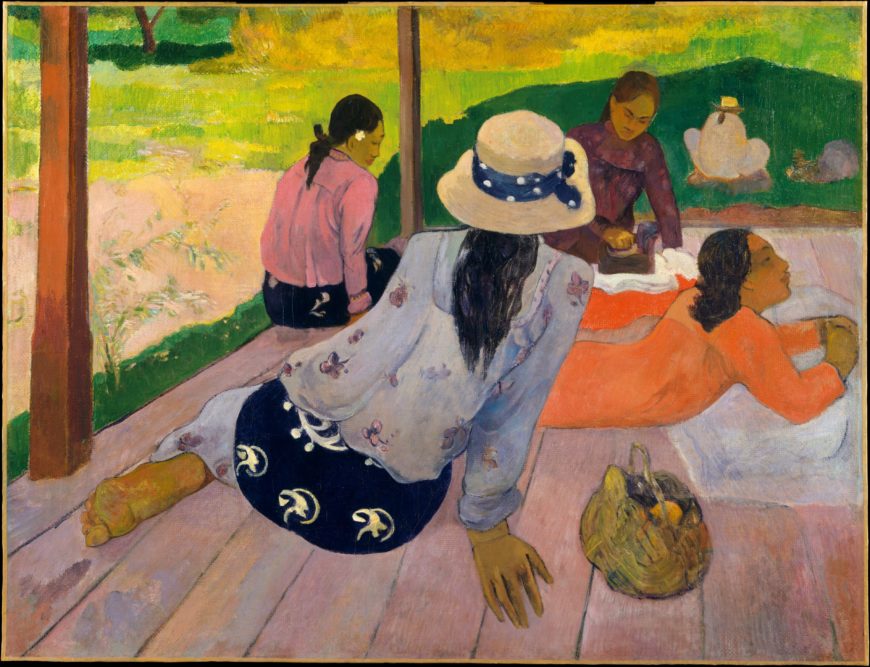

In a view consistent with other Europeans who visited North Africa, Matisse admired the Moroccans’ lifestyle, which appeared to him to be relaxed and contemplative. For Matisse, the goldfish came to symbolize this tranquil state of mind and, at the same time, became evocative of a paradise lost, a subject—unlike goldfish—frequently represented in art. Matisse was referring back to artists such as Nicolas Poussin (for example, Et in Arcadia ego), and Paul Gauguin (who painted during his travels to places like Tahiti).

The paradise theme is also prevalent in Matisse’s work. It found expression in Le Bonheur de vivre (The Joy of Life), and the goldfish should be understood as a kind of shorthand for paradise in Matisse’s painting. The mere name “gold-fish” defines these creatures as ideal inhabitants of an idyllic golden age, which it is fair to say Matisse was seeking when he travelled to North Africa. It is also likely that Matisse, who by 1912 was already familiar with the art of Islamic cultures, was interested in the meaning of gardens, water and vegetation in Islamic art—as well as symbolizing the beauty of divine creation, these were evocations of paradise.

Paul Gauguin, The Siesta (Atuona, Hiva Oa, Marquesas Islands), c. 1892–94, oil on canvas, 88.9 x 116.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Metaphor for the studio

However, Goldfish was not painted in Morocco. Henri Matisse painted it at home, in Issy-les-Moulineaux, near Paris. Matisse had moved to Issy in September 1909 to escape the pressures of Parisian life. So what you see here are Matisse’s own plants, his own garden furniture, and his own fish tank. The artist was drawn to the tank’s tall cylindrical shape, as this enabled him to create a succession of rounded contours with the top and bottom of the tank, the surface of the water and the table. Matisse also found the goldfish themselves visually appealing. Matisse painted Goldfish in his garden conservatory, where, like the goldfish, he was surrounded by glass.

Contemplation

Matisse distinguished predatory observation from disinterested contemplation, the latter being his preferred approach. Goldfish invites the viewer to indulge in the pleasure of watching the graceful movement and bright colors of the fish. Matisse once wrote that he dreamt of “an art of balance, of purity and serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter, an art that could be […] a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair that provides relaxation from fatigue.” This is precisely what Matisse wanted Goldfish to provide for the viewer.

Henri Matisse, Goldfish (detail), 1912, oil on canvas, 146 x 97 cm (Pushkin Museum of Art, Moscow)

Constructing pictorial space

The painting contains a tension created by Matisse’s depiction of space. The fish are seen simultaneously from two different angles. From the front, the goldfish are portrayed in such a way that the details of their fins, eyes and mouths are immediately recognizable to the viewer. Seen from above, however, the goldfish are merely suggested by colorful brushstrokes. If we then look at the plants through the transparent glass surface, we notice that they are distorted compared to the ‘real’ plants in the background.

Matisse paints the plants and flowers in a decorative manner. The upper section of the picture, above the fish tank, resembles a patterned wallpaper composed of flattened shapes and colors. What is more, the table-top is tilted upwards, flattening it and making it difficult for us to imagine how the goldfish and flowerpots actually manage to remain on the table. Matisse constructed this original juxtaposition of viewpoints and spatial ambiguity by observing Paul Cézanne’s still-life paintings. Cézanne described art as “a harmony parallel to nature”. And it is clear here that although Matisse was attentive to nature, he did not imitate it but used his image of it to reassemble his own pictorial reality. Although this can be confusing for the viewer, Matisse’s masterful use of color and pattern successfully holds everything together.

This painting is an illustration of some of the major themes in Matisse’s painting: his use of complimentary colors, his quest for an idyllic paradise, his appeal for contemplative relaxation for the viewer and his complex construction of pictorial space.

Additional Resources:

Matisse’s Goldfish and Sculpture, MoMA