One of the most recognized works by one of the least well-known artists

Giambologna’s Abduction of a Sabine Woman is one of the most recognized works of sixteenth-century Italian art by one of the least well-known artists of the period. And while Giambologna may not be a household name like Michelangelo, his influence on late sixteenth- and early seventeenth- century European art was extensive and long lasting. The Abduction of a Sabine Woman is located in a spot few tourists miss—the Loggia dei Lanzi, just outside of the Palazzo Vecchio, in Florence.

Giambologna, Mercury, c. 1586, bronze, 72cm high (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden)

The story of how Giambologna came to create the Sabine sculpture is almost as interesting as the historical tale it represents. Giambologna (born Jean du Boulogne in Douai in Flanders), arrived in Florence sometime around 1552, and within a few short years was court sculptor to the Medici and running his own large and productive workshop. Giambologna was highly regarded for his small to mid-size works in marble and bronze which were collected by connoisseurs and sent as Medicean diplomatic gifts all across Europe.

Giambologna and Mannerism

Giambologna’s works exemplified the characteristics of the Mannerist period, a time in which artists exploited the idea of beauty for beauty’s sake in works that showcased their artistic talent with figures composed of sinuous lines, graceful curves, exaggerated poses, and a hyper-elegance and preciousness that delighted viewers. His figure of Mercury (above) is an example of what made his work so popular.

While Giambologna’s fame and workshop flourished, there was one area in which he was not active, and that was in monumental sculpture. And in Florence, just taking the short walk from the Cathedral to the Palazzo Vecchio becomes a demonstration of the long history of life-size or larger public sculpture that dominated the cityscape. There were marble sculptures by such famous fifteenth-century sculptors as Donatello, Nanni di Banco, and Lorenzo Ghiberti on the façade of the cathedral, in the niches on the campanile (the belltower), and encircling the exterior of Orsanmichele, and in the Piazza della Signoria—the center of Florentine life and politics—were the truly monumental sculptures, including Michelangelo’s David (1504), Baccio Bandinelli’s Hercules and Cacus (1525-32), and Bartolommeo Ammanati’s Neptune Fountain (1565).

A sculptor of monumental works too

Thus, Giambologna also wanted to prove himself as a sculptor of monumental works. And as the story is told, Giambologna undertook the Sabine project without any specific subject in mind with the only goal being to produce a complex multi-figural group.[1] When the work was nearly complete and placed in the Loggia dei Lanzi in August of 1582, it was referred to simply as “group of three statues,” as no one knew what the subject was.[2] However, just a short time later, the work was interpreted as representing an ancient Roman event, and Giambologna produced a bronze narrative relief to be inserted into the base of the sculpture to help clarify the content of the three figures above.[3]

The subject

The subject is a dramatic one from ancient Roman history. According to the accounts of both Livy and Plutarch, after the city of Rome was founded in 750 B.C.E., the male population of the city was in need of women to ensure both the success of the city and the propagation of Roman lineage. After failed negotiations with the neighboring town of Sabine for their women, the Roman men devised a scheme to abduct the Sabine women (which they did during a summer festival).

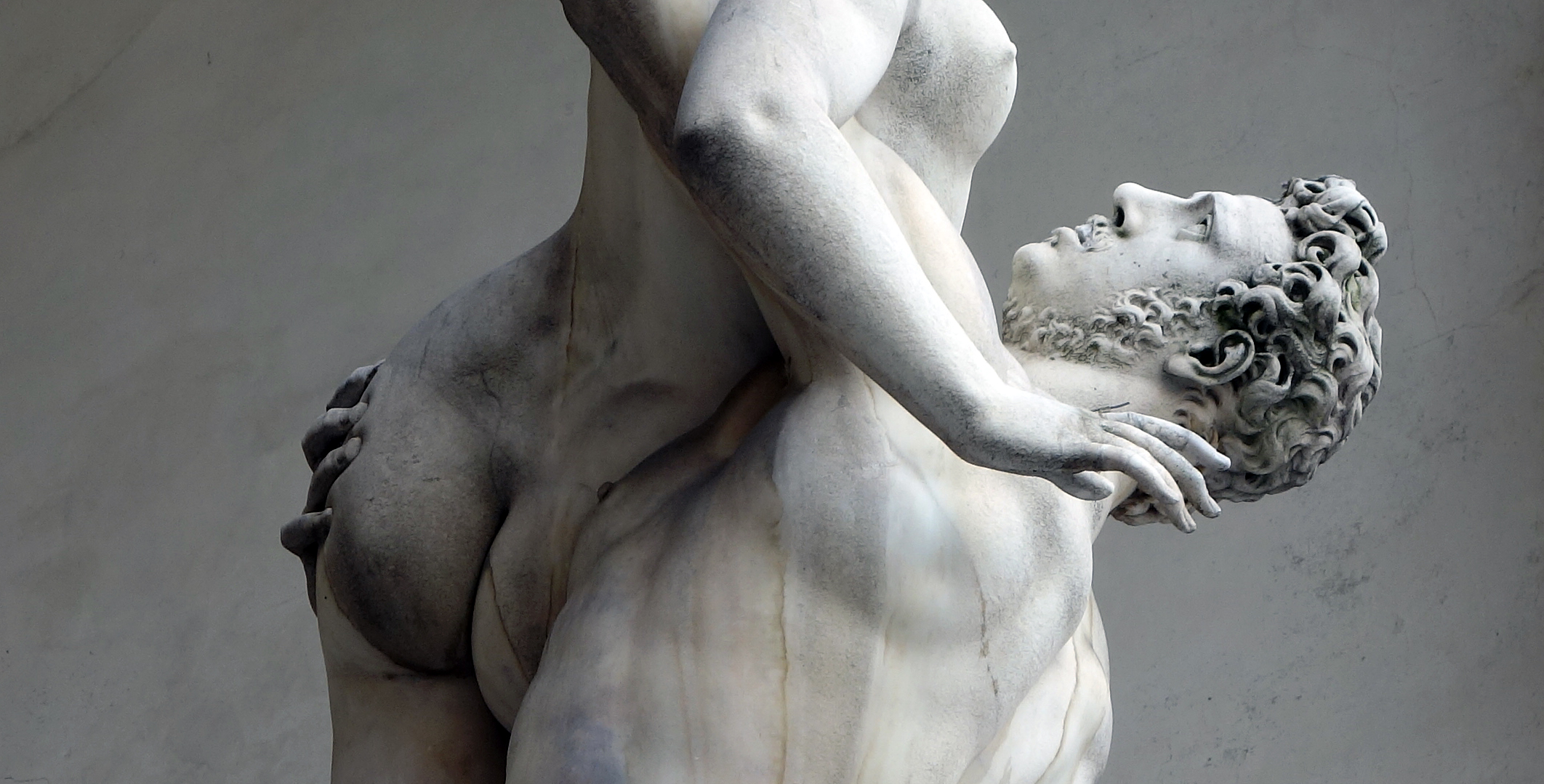

What we see in Giambologna’s sculpture is the moment when a Roman successfully captures a Sabine woman as he marches over a Sabine male who crouches down in defeat. (As a note, the sculpture is also referred to as the Rape of a Sabine Woman, which can lead to confusion over the subject. In Latin, the word rapito means “abduction” (and in Italian, the verb rapire means “to abduct,” thus the title Abduction of a Sabine Woman is technically more correct than the Rape of a Sabine Woman, which has explicit connotations of sexual violence. And indeed, in Livy’s account of the episode, he claims there was not sexual violence, rather a variety of enticements by the Roman for how the women would be treated as their wives.)[4])

A triumph

The Sabine was indeed a triumph for Giambologna. According to one account, when the work was officially unveiled to the Florentine public, not one person could find fault with it.[5] And if we compare the Sabine with another multi-figure group, such as Bandinelli’s two-figure Hercules and Cacus, it is immediately apparent how Giambologna dramatically altered the conception of a sculpture involving more than two figures. Bandinelli’s Hercules stands over a defeated Cacus, both men trapped in stony stillness. Neither figure expresses emotion or seems to possess the potential for movement.

In contrast, Giambologna built his figures up from the bottom, beginning with the cowering Sabine male (above), whose body twists and contorts in reaction to what is happening above him. The man’s straining muscles are evident as he raising his left hand up in despair as the triumphant Roman literally straddles his body, as he strides forward, carrying the Sabine woman away. If you look closely where he grabs her left hip, his fingers actually press into her flesh (below), thus amplifying the effect of these figures being more than marble statues. The woman herself, arms outstretched, twists back and over the Roman’s shoulder as she is hoisted into the air. These figures convey movement, aggression, fear, and struggle, as they move upward in a flame-like or twisting pattern known as figura serpentinata (serpentine figure), popular with Mannerist artists of the period. And to enhance the sense of frenetic energy, Giambologna did not provide a single or primary viewpoint for the work so the viewer must engage with the sculpture in 360 degrees in order to see the entirety of the drama unfold.

The Abduction of the Sabine Woman proved to be Giambologna’s entrée into the Florentine world of monumental sculpture. From this point forward he went on to create numerous other works that occupy principal sites in Florence, including the Cosimo I de’Medici Equestrian Monument in the Piazza della Signoria, St. Luke for a niche at Orsanmichele, and a brilliant Hercules Battling the Centaur, which is situated just a few feet from his Sabine group in the Loggia dei Lanzi.

Influence

The influence of what Giambologna accomplished with the Sabine group was seen through the next several decades. For example, in Gianlorenzo Bernini’s Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius we can most certainly begin to see the influence of Giambologna on the man who would become the face of Baroque sculpture in Italy. In Bernini’s Pluto and Proserpina, the forward stride of Pluto, the elevation of Proserpina above his head, his fingers pressing into the flesh of her thigh, and her outstretch arms and anguished face all point directly to the influence of Giambologna’s Sabine group. And it wasn’t only other sculptors who were responsive to Giambologna’s sculpture. Painters such as Nicolas Poussin and Pietro da Cortona both executed paintings of the same subject and clearly borrowed from both Giambologna’s Sabine figural group, but also his bronze narrative relief as well.

[1] Charles Avery, Giambologna. The Complete Sculpture (London: Phaidon Press Limited, 1993), 111.

[2] Ibid, 112.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Titus Livius, The History of Rome (Ab Urbe Condia Libri, c. 27-25 B.C.E.), Book 1, chapters 9-10.

[5] Avery, pp. 112-114.

Additional resources:

Giambologna at the Google Cultural Institute

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”GiambolognaSabine”]